THD203 2000 Words Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Considerations for a Study of a Musical Instrumentality in the Gameplay of Video Games

Playing in 7D: Considerations for a study of a musical instrumentality in the gameplay of video games Pedro Cardoso, Miguel Carvalhais ID+, Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract. The intersection between music and video games has been of increased interest in academic and in commercial grounds, with many video games classified as ‘musical’ having been released over the past years. The purpose of this paper is to explore some fundamental concerns regarding the instrumentality of video games, in the sense that the game player plays the game as a musical or sonic instrument, an act in which the game player becomes a musical performer. We define the relationship between the player and the game system (the musical instrument) to be action- based. We then propose that the seven discerned dimensions we found to govern that relationship to also be a source of instrumentality in video games. Something that not only will raise a deeper understanding of musical video games but also on how the actions of the player are actually embed in the generation and performance of music, which, in some cases, can be transposed to other interactive artefacts. In this paper we aim at setting up the grounds for discussing and further develop our studies of action in video games intersecting it with that of musical performance, an effort that asks for multidisciplinary research in musicology, sound studies and game design. Keywords: Action, Gameplay, Music, Sound, Video games. Introduction Music and games are no exception when it comes to the ubiquity of computational systems in contemporary society. -

An Archaeology of Music Video Games

Journal of Sound, Silence, Image and Technology 41 Issue 3 | December 2020 | 41-51 ISSN 2604-451X An Archaeology of Music Video Games Israel V. Márquez Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] Date received: 1-10-2020 Date of acceptance: 30-10-2020 KEY WORDS: MEDIA ARCHAEOLOGY | NEW MEDIA | MUSIC VIDEO GAMES | SOUND | IMAGE | NOVELTY Journal of Sound, Silence, Image and Technology | Issue 3 | December 2020 42 An Archaeology of Music Video Games ABSTRACT This article is a contribution to the study of video games – and more specifically, of so-called “music video games” – from an archaeological perspective. In recent years, much academic attention has been paid to the archaeology of media as an area of knowledge thanks to its ability to construct alternative narratives for media that were previously rejected or forgotten, in addition to offering resistance to the rhetoric around digital and its emphasis on change and innovation. Studies on new media, including those dedicated to video games, often share a disregard for the past (Huhtamo and Parikka, 2011, p. 1), something that is also observed in specific genres such as music video games. Starting from these and other premises, the aim of this article is to understand music video games from an archaeological point of view that allows us to go beyond the rhetoric of change and novelty linked to modern digital and three-dimensional versions of this type of video game. Journal of Sound, Silence, Image and Technology | Issue 3 | December 2020 43 An Archaeology of Music Video Games Introduction The so-called archaeology of media, or “media archaeology”, has been of great interest to academics for several years, especially in the Anglo-Saxon and Central European sphere and increasingly in the Spanish-speaking academic community. -

Super Mario Portal Game

1 / 2 Super Mario Portal Game Lessons of Game Design learned from Super Mario Maker ... The portal gun is one of those mechanics that sounds like it has an unlimited .... The game combines the elements of the two popular video games: the platforming Super Mario Bros and the puzzle solving Portal. The game retains the traditional .... It's a mashup of Nintendo's classic Super Mario Bros. platform game with Portal. That's right – Mario now has a portal gun, which he can use to .... New Super Mario Bros. U is a game ... Portal 2, like Minecraft, is a highly popular console game that encourages experimentation and flexibility.. Last August we were promised to be able to play the classic Super Mario Bros. with 1 major difference integrated into the game. Aperature ... mario portal game · super mario bros meets portal game · blue television games portal mario.. Mario Bros Mappack Portal Mappack Mari0 Bros Mappack No WW Mari0 ... If you enjoy this game then also play games Super Mario Bros. and Super Mario 64.. Much like nuts and gum, Portal and Super Mario Bros. are together at last.. Click on this exciting game of the classic Super Mario bros, Portal Mario bros 64. You must help the famous Mario bros to defend himself from all his enemies in .... and Portal hybrid from indie game developer Stabyourself.net. Yup, it's the old Super Mario Bros. with portal guns, user created content, a map .... Mario and Portal, a perfect mix. Super Smash Flash 2. A fun game inspired by Super Smash Bros. -

CPR for the Arcade Culture a Case History on the Development of the Dance Dance Revolution Community

CPR for the Arcade Culture A Case History on the Development of the Dance Dance Revolution Community Alexander Chan SUID 5075504 STS 145: History of Computer Game Design Stanford University March 16, 2004 Introduction Upon entering an arcade, you come across an unusual spectacle. Loud Japanese techno and a flashing neon glow pour out of the giant speakers and multicolored lights of an arcade console at the center of the room. Stranger than the flashy arcade cabinet is the sweaty teenager stomping on a metal platform in front of this machine, using his feet to vigorously press oversized arrows as the screen in front of him displays arrows scrolling upward. A growing group of people crowd around to watch this unusual game-play, cheering the player on. In large letters, the words “Dance Dance Revolution 3rd Mix” glow above the arcade machine. Most people who stumble upon a scene similar to this one would rarely believe that such a conceptually simple arcade game could foster an enormous nation-wide game community, both online and offline. Yet the rules of the game are deceptively simple. The players (one or two) must press the arrows on the platform (either up, down, left, or right) when the corresponding arrows on the screen reach the top, usually on beat with the techno/pop song being played. If the player doesn’t press the arrows on time, the song will quickly come to an end, and the machine will Arrows scrolling up a DDR screen ask for more quarters to continue play. Yet despite its simplicity, Dance Dance Revolution, or DDR for short, has helped create a giant player community in the United States, manifesting itself though various forms. -

IEEE Gamesig Intercollegiate Game Showcase 2018 Game Overview: Super Nova______Date: 4-11-18

IEEE GameSIG Intercollegiate Game Showcase 2018 Game Overview: Super Nova______________ Date: 4-11-18 One-Sentence Inspired by PaRappa the Rapper, Super Nova is a VR game that Description blends rap battles and RPG elements into a rhythm game. List of Team Andrew Barnes, Main School: LCAD ([email protected]) Members and Xueqing Liu, USC ([email protected]) Their Schools Ruoyu Wang, USC ([email protected]) Main Contact: (949) 887-9210 School Level _X_ College/University ___ High School Target Platform VR: Oculus and VIVE and Audience Teen. VR and rhythm game enthusiasts. One-Paragraph In the Super Nova rap battle demo, the player will experience a Summary of virtual rap battle with an NPC friend in front of a corner barbershop. Gameplay and The rap battle has two modes: A defense mode to block raps and Objectives an offense mode to rap. Key Features • Musical rhythm action Art Game • Emotional connection to the game through music and rhythm • First-Person VR and expanding on games like Rhythm Heaven • Two musical game types: Action Defense Rhythm and Lyrical Offense Rhythm (Music Video) • Visual music elements in levels and attached to geometry Thumbnails of Game Art Software Libraries Unity 2017, Koreographer, VRTK, Adobe Fuse, Mixamo, Maya and Packages Used Third-Party and Unity Asset: City Block Pack Ready Made Asset Credits Faculty Member Sandy Appleoff, LCAD ([email protected]) Name & Contact School: (949) 376-6000 Mobile: (785) 393-9070 Information YouTube Link https://youtu.be/lo4i7_m6PE4 Misc. Notes https://vrhymes.com/ Submitted by: Andrew Barnes, [email protected] (949) 887-9210 List of game assets not entirely made by the team. -

20-22 August 2018 the National Videogame Arcade REPLAYING JAPAN 2018

Replaying Japan 2018 20-22 August 2018 The National Videogame Arcade www.thenva.com REPLAYING JAPAN 2018 LOCAL ORGANISERS Alice Roberts, Iain Simons, James Newman and the team at The National Videogame Arcade CONFERENCE CO-ORGANISERS Ritsumeikan Center for Game Studies, Ritsumeikan University Philosophy and Humanities Computing, University of Alberta Institute of East Asian Studies / Japanese Studies, Leipzig University Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA) Japan CONFERENCE CHAIRS Geoffrey ROCKWELL, Philosophy and Humanities Computing, University of Alberta Akinori NAKAMURA, College of Image Arts and Sciences, Ritsumeikan University Jérémie PELLETIER-GAGNON, Comparative Literature and Humanities Computing, University of Alberta Martin PICARD, Institute of East Asian Studies / Japanese Studies, Leipzig University Martin ROTH, Institute of East Asian Studies / Japanese Studies, Leipzig University PROGRAMME COMMITTEE Koichi HOSOI, College of Image Arts and Sciences, Ritsumeikan University Kazufumi FUKUDA, Ritsumeikan Global Innovation Research Organization, Ritsumeikan University Akito INOUE, Graduate School of Core Ethics and Frontier Sciences, Ritsumeikan University Shuji WATANABE, College of Image Arts and Sciences, Ritsumeikan University Tsugumi OKABE, Comparative Literature, University of Alberta Mitsuyuki INABA, College of Policy Science, Ritsumeikan University Hiroshi YOSHIDA, Graduate School of Core Ethics and Frontier Science, Ritsumeikan University !2 of !56 THE NATIONAL VIDEOGAME ARCADE The National Videogame Arcade is a not-for-profit organisation that exists to develop the role of videogames in culture, education and society. It is funded by revenue generated by visitors, hospitality and events as well as generous patrons. The National Videogame Arcade opened in March 2015 and welcomes tens of thousands of visitors a year. As well as the core visitor attraction, we also deliver education programmes to school visits and informal learners. -

Building a Music Rhythm Video Game Information Systems and Computer

Building a music rhythm video game Ruben Rodrigues Rebelo Thesis to obtain the Master of Science Degree in Information Systems and Computer Engineering Supervisor: Prof. Rui Filipe Fernandes Prada Examination Committee Chairperson: Nuno Joao˜ Neves Mamede Supervisor: Prof. Rui Filipe Fernandes Prada Member of the Committee: Carlos Antonio´ Roque Martinho November 2016 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my supervisor, Prof. Rui Prada for the support and for making believe that my work in this thesis was not only possible, but also making me view that this work was important for myself. Also I want to thank Carla Boura Costa for helping me through this difficult stage and clarify my doubts that I was encountered this year. For the friends that I made this last year. Thank you to Miguel Faria, Tiago Santos, Nuno Xu, Bruno Henriques, Diogo Rato, Joana Condec¸o, Ana Salta, Andre´ Pires and Miguel Pires for being my friends and have the most interesting conversations (and sometimes funny too) that I haven’t heard in years. And a thank you to Vaniaˆ Mendonc¸a for reading my dissertation and suggest improvements. To my first friends that I made when I entered IST-Taguspark, thank you to Elvio´ Abreu, Fabio´ Alves and David Silva for your support. A small thank you to Prof. Lu´ısa Coheur for letting me and my origamis fill some of the space in the room of her students. A special thanks for Inesˆ Fernandes for inspire me to have the idea for the game of the thesis, and for giving special ideas that I wish to implement in a final version of the game. -

Music Games Rock: Rhythm Gaming's Greatest Hits of All Time

“Cementing gaming’s role in music’s evolution, Steinberg has done pop culture a laudable service.” – Nick Catucci, Rolling Stone RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME By SCOTT STEINBERG Author of Get Rich Playing Games Feat. Martin Mathers and Nadia Oxford Foreword By ALEX RIGOPULOS Co-Creator, Guitar Hero and Rock Band Praise for Music Games Rock “Hits all the right notes—and some you don’t expect. A great account of the music game story so far!” – Mike Snider, Entertainment Reporter, USA Today “An exhaustive compendia. Chocked full of fascinating detail...” – Alex Pham, Technology Reporter, Los Angeles Times “It’ll make you want to celebrate by trashing a gaming unit the way Pete Townshend destroys a guitar.” –Jason Pettigrew, Editor-in-Chief, ALTERNATIVE PRESS “I’ve never seen such a well-collected reference... it serves an important role in letting readers consider all sides of the music and rhythm game debate.” –Masaya Matsuura, Creator, PaRappa the Rapper “A must read for the game-obsessed...” –Jermaine Hall, Editor-in-Chief, VIBE MUSIC GAMES ROCK RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME SCOTT STEINBERG DEDICATION MUSIC GAMES ROCK: RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME All Rights Reserved © 2011 by Scott Steinberg “Behind the Music: The Making of Sex ‘N Drugs ‘N Rock ‘N Roll” © 2009 Jon Hare No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical – including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Syllabus (Holly Newman

Master of Entertainment Industry Management Course The Business of Gaming Information Course Number: 93-857 Semester Credit Hours: 4, Class Meetings: 4 Instructor: Holly Newman Email: [email protected] Saturday, 10/24 at 10am Saturday, 11/7 at 10am Saturday, 11/14 at 10am Saturday, 11/21 at 10am *Syllabus subject to change and readings will be assigned closer to the date to ensure current issues are involved. Description This four-week class will focus on the business aspects that relate to the gaming industry. This industry has grown quickly in the last 25 years. With 2020 sales anticipated to reach $159 billion in game content, hardware and accessories, games have emerged as a leading source of commercial entertainment – in content development, distribution and the licensing of its IP. The course will focus on the ways in which its creative and business practices are both unique, and also share common characteristics with other forms of screen-based entertainment. The course will focus on the following key areas: - The publishing business model, and how Games evolved from and relate to software distribution. Covered material will include: licensing agreements, the development and ownership of Intellectual Property. - The game publishers, and an overview of the key companies and competing business strategies, including game genres, key titles/franchises, management of developer relationships, and the publishers’ relationships with licensors and licensees (primarily vis-à-vis the motion picture business). - The lexicon and how to effectively communicate with buyers and sellers of Intellectual Property. - The production process and how to reconcile with film and television production timelines and milestones. -

Game Developer

ANNIVERSARY10 ISSUE >>PRODUCT REVIEWS TH 3DS MAX 6 IN TWO TAKES YEAR MAY 2004 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>VISIONARIES’ VISIONS >>JASON RUBIN’S >>POSTMORTEM THE NEXT 10 YEARS CALL TO ACTION SURREAL’S THE SUFFERING THE BUSINESS OF EEVERVERQQUESTUEST REVEALEDREVEALED []CONTENTS MAY 2004 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 5 FEATURES 18 INSIDE EVERQUEST If you’re a fan of making money, you’ve got to be curious about how Sony Online Entertainment runs EVERQUEST. You’d think that the trick to running the world’s most successful subscription game 24/7 would be a closely guarded secret, but we discovered an affable SOE VP who’s happy to tell all. Read this quickly before SOE legal yanks it. By Rod Humble 28 THE NEXT 10 YEARS OF GAME DEVELOPMENT Given the sizable window of time between idea 18 and store shelf, you need to have some skill at predicting the future. We at Game Developer don’t pretend to have such skills, which is why we asked some of the leaders and veterans of our industry to give us a peek into what you’ll be doing—and what we’ll be covering—over the next 10 years. 36 28 By Jamil Moledina POSTMORTEM 32 THE ANTI-COMMUNIST MANIFESTO 36 THE GAME DESIGN OF SURREAL’S Jason Rubin doesn’t like to be treated like a nameless, faceless factory worker, and he THE SUFFERING doesn’t want you to be either. At the D.I.C.E. 32 Before you even get to the problems you typically see listed in our Summit, he called for lead developers to postmortems, you need to nail down your design. -

Move Over Shamu As Dolphin Friends Makes a Splash on DS

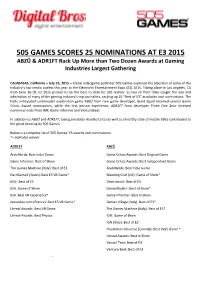

505 GAMES SCORES 25 NOMINATIONS AT E3 2015 ABZÛ & ADR1FT Rack Up More than Two Dozen Awards at Gaming Industries Largest Gathering CALABASAS, California – July 23, 2015 – Global videogame publisher 505 Games captured the attention of some of the industry’s top media outlets this year at the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) 2015. Taking place in Los Angeles, CA from June 16-18, E3 2015 proved to be the best to date for 505 Games’ as two of their titles caught the eye and admiration of many of the gaming industry’s top journalists, racking up 25 “Best of E3” accolades and nominations. The hotly anticipated underwater exploration game ABZÛ from new game developer, Giant Squid received several Game Critics Award nominations, while the first person experience, ADR1FT from developer Three One Zero received numerous nods from IGN, Game Informer and Venturebeat. In addition to ABZÛ and ADR1FT, racing simulator Assetto Corsa as well as a healthy slate of mobile titles contributed to the great showing by 505 Games. Below is a complete list of 505 Games’ E3 awards and nominations: *= Indicates winner ADR1FT ABZÛ Arab Nerds: Best Indie Game Game Critics Awards: Best Original Game Game Informer: Best of Show Game Critics Awards: Best Independent Game The Games Machine (Italy): Best of E3 Arab Nerds: Best Indie Game HardGame2 (Spain): Best E3 VR Game* Bleeding Cool (UK): Game of Show* IGN: Best of E3 Destructoid: Best of E3 IGN: Game of Show GamesRadar+: Best of Show* IGN: Best VR Experience* Game Informer: Best in Show Jeuxvideo.com (France): Best E3 VR Game* Games Village (Italy): Best of E3* Unreal Awards: Best VR Game The Games Machine (Italy): Best of E3* Unreal Awards: Best Physics IGN: Game of Show IGN (Italy): Best of E3 Playstation Universe (Canada): Best Indie Game * Unreal Awards: Best in Show Yahoo! Tech: Best of E3 Venture Beat: Best of E3 - ADR1FT will be available for Playstation®4, Xbox One and STEAM.