Ozymandias: Kings Without a Kingdom Kevin Kshitiz Bhatia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Responsibilities of the Music Executive

Chapter II Responsibilities of the Music Executive Frederick Miller, Dean Emeritus School of Music, DePaul University Administrative Organization in Academia In virtually all academic institutions, ultimate authority rests with a governing board, that is, trustees, regents, whatever. As a practical matter, much of the board’s authority is delegated to the president, who retains as much as he or she needs to do the job and passes along the rest to the next person in the institutional chain of command, typically the provost. That person, in turn, keeps what is needed for that office and gives the rest to the deans and department chairs in this downward flow of authority in academia. Whatever title the music executive may hold—dean, chair, and so on—the position will typically be thought of as “middle management.” Others in the academic hierarchy— president, provost, vice presidents—are seen as “upper management,” and as some cynics might view it, hardly anyone is lower than a dean. However accurate this may be, mid-level administrative positions in higher education possess an unmistakable fragility. It stems from the fact that while we may be tenured in our faculty positions, at some professorial rank, we are not tenured in our administrative positions. We are positioned in the hierarchy between faculty, many or most of whom are tenured in their roles, and the upper administration, who typically are less subject to periodic, formal review. We spend much of our time in adversarial relationships with one of these groups on behalf of the other. That is, we may be pressing the upper administration on behalf of some faculty need. -

Panelists Biographies

Public Workshop on Competition in Licensing Music Public Performance Rights July 28-29, 2020 Panelist Biographies July 28, 2020 Session 1: Remarks from Stakeholders on the Consent Decrees David Israelite, President and CEO, National Music Publishers’ Association (NMPA) David Mark Israelite is the President and Chief Executive Officer of the National Music Publishers’ Association. The National Music Publishers' Association (NMPA) is the premier trade association representing American music publishers and their songwriter partners. The NMPA's mandate is to protect and advance the interests of music publishers and their songwriter partners in matters relating to the domestic and global protection of music copyrights. From 2001 through 2005, Israelite served as Deputy Chief of Staff and Counselor to the Attorney General of the United States. In this capacity he served as the Attorney General’s personal advisor on all legal, strategic and public affairs issues. In March of 2004, the Attorney General appointed Israelite Chairman of the Department’s Task Force on Intellectual Property. Prior to joining the Department of Justice, he served as the Director of Political and Governmental Affairs for the Republican National Committee. In that role he was the senior advisor to the Chairman of the National Republican Party. From 1997 through 1998, he served as Missouri Senator Kit Bond’s Administrative Assistant, making him the youngest AA in the United States Senate. He also served as Campaign Manager for Senator Bond’s successful 1998 re-election campaign. From 1994 through 1997, Israelite practiced law in the Commercial Litigation Department at the firm of Bryan Cave, LLP in Kansas City, Missouri. -

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: a Content Analysis

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: A Content Analysis Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Manriquez, Candace Lynn Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 03:10:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624121 THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN IN RAP VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Candace L. Manriquez ____________________________ Copyright © Candace L. Manriquez 2017 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 Running head: THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR The thesis titled The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman: A Content Analysis prepared by Candace Manriquez has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a master’s degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

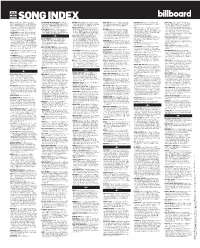

2021 Song Index

FEB 20 2021 SONG INDEX 100 (Ozuna Worldwide, BMI/Songs Of Kobalt ASTRONAUT IN THE OCEAN (Harry Michael BOOKER T (RSM Publishing, ASCAP/Universal DEAR GOD (Bethel Music Publishing, ASCAP/ FIRE FOR YOU (SarigSonnet, BMI/Songs Of GOOD DAYS (Solana Imani Rowe Publishing Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI/Music By Publishing Deisginee, APRA/Tyron Hapi Publish- Music Corp., ASCAP/Kid From Bklyn Publishing, Cory Asbury Publishing, ASCAP/SHOUT! MP Kobalt Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI) Designee, BMI/Songs Of Universal, Inc., BMI/ RHLM Publishing, BMI/Sony/ATV Latin Music ing Designee, APRA/BMG Rights Management ASCAP/Irving Music, Inc., BMI), HL, LT 14 Brio, BMI/Capitol CMG Paragon, BMI), HL, RO 23 Carter Lang Publishing Designee, BMI/Zuma Publishing, LLC, BMI/A Million Dollar Dream, (Australia) PTY LTD, APRA) RBH 43 BOX OF CHURCHES (Lontrell Williams Publish- CST 50 FIRES (This Little Fire, ASCAP/Songs For FCM, Tuna LLC, BMI/Warner-Tamerlane Publishing ASCAP/WC Music Corp., ASCAP/NumeroUno AT MY WORST (Artist 101 Publishing Group, ing Designee, ASCAP/Imran Abbas Publishing DE CORA <3 (Warner-Tamerlane Publishing SESAC/Integrity’s Alleluia! Music, SESAC/ Corp., BMI/Ruelas Publishing, ASCAP/Songtrust Publishing, ASCAP), AMP/HL, LT 46 BMI/EMI Pop Music Publishing, GMR/Olney Designee, GEMA/Thomas Kessler Publishing Corp., BMI/Music By Duars Publishing, BMI/ Nordinary Music, SESAC/Capitol CMG Amplifier, Ave, ASCAP/Loshendrix Production, ASCAP/ 2 PHUT HON (MUSICALLSTARS B.V., BUMA/ Songs, GMR/Kehlani Music, ASCAP/These Are Designee, BMI/Slaughter -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

How to Use Inclusion Riders to Increase Gender Diversity in the Music Industry

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Law School Student Scholarship Seton Hall Law 2019 Can't Hold Us Down”1: How to Use Inclusion Riders to Increase Gender Diversity in the Music Industry Laura Kozel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kozel, Laura, "Can't Hold Us Down”1: How to Use Inclusion Riders to Increase Gender Diversity in the Music Industry" (2019). Law School Student Scholarship. 1019. https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship/1019 ABSTRACT Despite improvements in female visibility and a number of movements pushing for equality in recent years, gender imbalance continues to plague the world of entertainment. While strides have been made to achieve parity in the film industry, little progress has been made to achieve the same in music where the disproportionality of females is even worse. Females are chronically underrepresented across virtually all aspects of music, both on-stage and off-stage, whether it be as musicians or as executives, which subsequently effects the amount of nominations, as well as awards that females in music receive. The implementation of inclusion riders in Hollywood has demonstrably improved female representation in popular films, but until now inclusion riders have not been applied to the music industry. This paper explores the application of inclusion riders to the music industry in order to remedy a long-standing history of female exclusion, as well as increase visibility for the vast number of talented females in the music industry that deserve the same opportunities and recognition, but until now have remained invisible. -

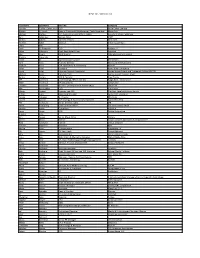

NYME 2017 Attendee List.Xlsx

NYME 2017 Attendee List First Name Last Name Job Title Company Tiombe "Tallie" Carter, Esq. CEO Tallie Carter Law Esq Wesley A'Harrah Head of Training & Development, Tools Reporting Music Ally Michael Abitbol SVP, Business & Legal Affairs, Digital Sony/ATV Music Publishing Dan Ackerman Section Editor CNET Andrea Adams Director of Sales FilmTrack Andrew Adler Director Citrin Cooperman Stella Ahn Turki Al Shabanah CEO Rotana TV Philip Alberstat Chief Operating Officer Contend Jake Alcorn MBA Student Columbia Business School Brianna Alexander Sarah Ali Operation and Support Streamlabs June Alian Publicity Director Skybound Entertainment Graham Allan EVP, Operations & Consulting KlarisIP Karen Allen President Karen Allen Consulting Susan Allen Attorney Advisor (Copyright) United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) Michele Amar Director / CEO Bureau Export / France Rocks Danny Anders CEO & Founder ClearTracks Jeff Anderson Chief Strategy Officer and GM Bingo Bash - GSN Games Mark Anderson VP Global Sales LumaForge Stephen Anderson Business Development & Partnerships Octane AI Alec Andronikov CEO The Visory Manny Anekal Founder and CEO The Next Level and Versus Sports Debbie Anjos Marketing Manager Gerber Life Insurance Farooq Ankalagi Sr. Director Mindtree Lauren Apolito SVP Strategy & Business Development Rumblefish/HFA Phil Ardizzone Senior Director, Sales IAB Mario Armstrong Chief Content Officer The Never Settle Show Kwadjo Asare Consultant FIGHTER Kwasi Asare CEO Fighter Interactive Nuryani Asari Jem Aswad Senior Music Editor Variety -

Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Empowerment and Enslavement: Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G. Rollins-Haynes Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES EMPOWERMENT AND ENSLAVEMENT: RAP IN THE CONTEXT OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN CULTURAL MEMORY By LEVERN G. ROLLINS-HAYNES A Dissertation submitted to the Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities (IPH) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Levern G. Rollins- Haynes defended on June 16, 2006 _____________________________________ Charles Brewer Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________________ Xiuwen Liu Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Maricarmen Martinez Committee Member _____________________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member Approved: __________________________________________ David Johnson, Chair, Humanities Department __________________________________________ Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my husband, Keith; my mother, Richardine; and my belated sister, Deloris. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Very special thanks and love to -

NEWSLETTER a N E N T E R T a I N M E N T I N D U S T R Y O R G a N I Z a T I On

October 2012 NEWSLETTER A n E n t e r t a i n m e n t I n d u s t r y O r g a n i z a t i on What does a music producer do, anyway? By Ian Shepherd The term ‘music producer’ means different things to different The President’s Corner people. Some are musicians, some are engineers, some are remixers. So what does a music producer actually do ? Big thanks tonight to Kent Liu and Michael Morris for putting together such an impressive panel of producers. In very pragmatic terms, the producer is a ‘project manager’ for As a reminder, we are able to provide & present this type the recording, mixing and mastering process. of dinner meeting because of our corporate and individual She has an overall vision for the music, the sound and the goals memberships, so please go to theccc.org today and renew of the project, and brings a unique perspective to inspire, assist your membership – we appreciate your support (and the and sometimes provoke the artists. membership pays for itself if you attend our meetings on a regular basis). See you in November!! The producer should make the record more than the sum of its parts – you could almost say she is trying to create musical alchemy. Eric Palmquist Every producer brings different skills and a different approach, President, California Copyright Conference. and this can make what they do difficult to summarize. In this post I’ve identified seven distinct types of record producer to try and make this clearer. -

Countrybreakout Radio Chart on March 19

March 19, 2021 The MusicRow Weekly Friday, March 19, 2021 Coming Soon: The 56th Academy of SIGN UP HERE (FREE!) Country Music Awards If you were forwarded this newsletter and would like to receive it, sign up here. THIS WEEK’S HEADLINES 56th annual ACM Awards Warner Chappell Music / Amped Entertainment Sign KK Johnson Jim Catino To Exit Sony Music Nashville NSAI Promotes Jennifer Turnbow To COO Jimmie Allen Renews With The 56th Academy of Country Music Awards are less than a month away. Endurance Music Group Honoring the biggest names and emerging talent in country music, the 56th ACM Awards will broadcast live from three iconic country music Samantha Borenstein venues: the Grand Ole Opry House, Nashville’s historic Ryman Auditorium Launches Management Firm and The Bluebird Cafe on Sunday, April 18 (8:00-11:00 PM, live ET/ delayed PT) on the CBS Television Network. Ross Copperman Signs With Photo Finish Records Voting for the 56th ACM Awards opened on March 17, and closes Wednesday, March 24. Tigirlily Signs With Monument Maren Morris and Chris Stapleton lead the nominations with six each. Records Stapleton, Luke Bryan, Eric Church, Luke Combs, and Thomas Rhett Miranda Lambert, Dan + are nominated for the top honor, Entertainer of the Year. Shay, John Prine Among Grammy Winners Reigning Entertainer of the Year Rhett has four nominations, including his second nomination for Entertainer of the Year. DISClaimer Singles Reviews Combs and Stapleton are both nominees for Entertainer of the Year. A win And much more… for either artist in that category will also clinch the coveted Triple Crown Award, which consists of an Entertainer of the Year win, plus wins in an act's respective New Artist (male, female, or duo or group) and Artist (male, female, duo or group) categories. -

Super ACRONYM - Round 5

Super ACRONYM - Round 5 1. After retiring, this athlete founded the Crest Computer Supply Company and served as the athletic director of Southern Illinois University. This player claimed to only need "18 inches of daylight" and led the NFL in the majority of both rushing and kick return categories in 1966. This Wichita-born athlete was often called the (*) "Kansas Comet." This man's autobiography I Am Third detailed his close relationship with his roommate of a different race, which was adapted into a film in which this man was played by Billy Dee Williams. The late Brian Piccolo was a dear friend of, for 10 points, what Bears running back? ANSWER: Gale (Eugene) Sayers <Nelson> 2. The Tiny Desk, a prototype devised by this character, allows people to alleviate stress by flipping their office desks without creating a huge mess. This man sings about a "Leprechaun on the lawn at Boston Common" and a creature "the size of (*) Luxembourg" as part of a "Kaiju Rap" inspired by the film Reptilicus. This character is tormented by Max, an assistant played by Patton Oswalt, and Kinga, played by Felicia Day. For 10 points, name this "mug in a yellow jumpsuit" who is trapped "on the dark side of the moon" in the revival of Mystery Science Theater 3000 and is played by a namesake comedian with the surname Ray. ANSWER: Jonah Heston (accept either underlined portion; do not accept or prompt on "(Jonah) Ray") <Vopava> 3. After the Creolettes were renamed for these things, they recorded the song "The Wallflower (Dance With Me Henry)" with Etta James. -

CWR Sender ID and Codes

CWR Sender ID Codes CWR06-1972_Specifications_Overview_CWR_sender_ID_and_codes_2021-09-27_EN.xlsx Publisher Submitter Code Submitter Start Date End Date (dd/mm/yyyy) Number (dd/mm/yyyy) To all societies 00 Royal Flame Music Gmbh 104 00585500247 21/08/2015 Rdb Conseil Rights Management 112 00869779543 6/01/2020 Mmp.Mute.Music.Publishing E.K. 468 814224861 25/07/2019 Seegang Musik Musikverlag E.K. 772 792755298 25/07/2019 Les Editions Du 22 Decembre 22D 450628759 4/11/2010 3tone Publishing Limited 3TO 1050225416 25/09/2020 4AD Music Limited 4AD 293165943 15/03/2010 5mm Publishing 5MM 00492182346 22/11/2017 AIR EDEL ASSOCIATES LTD AAL 69817433 7/01/2009 Ceg Rights Usa AAL 711581465 17/12/2013 Ambitious Media Productions AAP 00868797449 31/08/2021 Altitude Balloon AB 722094072 6/11/2013 Abc Digital Distribution Limited ABC 00599510310 8/06/2020 Editions Abinger Sprl ABI 00858918083 23/11/2020 Abkco Music Inc ABM 00056388746 21/11/2018 ABOOD MUSIC LIMITED ABO 420344502 31/03/2009 Alba Blue Music Publishing ABP 00868692763 2/06/2021 Abramus Digital Servicos De Identificacao De Repertorio ABR 01102334131 16/07/2021 Ltda Absilone Technologies ABS 00546303074 5/07/2018 Almo Music of Canada AC 201723811 1/08/2001 2/10/2006 Accorder Music Publishing America ACC 606033489 5/09/2013 Accorder Music Publishing Ltd ACC 574766600 31/01/2013 Abc Frontier Inc ACF 01089418623 20/07/2021 Galleryac Music ACM 00600491389 24/04/2017 Alternativas De Contenido S L ACO 01033930195 17/12/2020 ACTIVE MUSIC PUBLISHING PTY LTD ACT 632147961 16/11/2016 Audiomachine