Responsibilities of the Music Executive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panelists Biographies

Public Workshop on Competition in Licensing Music Public Performance Rights July 28-29, 2020 Panelist Biographies July 28, 2020 Session 1: Remarks from Stakeholders on the Consent Decrees David Israelite, President and CEO, National Music Publishers’ Association (NMPA) David Mark Israelite is the President and Chief Executive Officer of the National Music Publishers’ Association. The National Music Publishers' Association (NMPA) is the premier trade association representing American music publishers and their songwriter partners. The NMPA's mandate is to protect and advance the interests of music publishers and their songwriter partners in matters relating to the domestic and global protection of music copyrights. From 2001 through 2005, Israelite served as Deputy Chief of Staff and Counselor to the Attorney General of the United States. In this capacity he served as the Attorney General’s personal advisor on all legal, strategic and public affairs issues. In March of 2004, the Attorney General appointed Israelite Chairman of the Department’s Task Force on Intellectual Property. Prior to joining the Department of Justice, he served as the Director of Political and Governmental Affairs for the Republican National Committee. In that role he was the senior advisor to the Chairman of the National Republican Party. From 1997 through 1998, he served as Missouri Senator Kit Bond’s Administrative Assistant, making him the youngest AA in the United States Senate. He also served as Campaign Manager for Senator Bond’s successful 1998 re-election campaign. From 1994 through 1997, Israelite practiced law in the Commercial Litigation Department at the firm of Bryan Cave, LLP in Kansas City, Missouri. -

How to Use Inclusion Riders to Increase Gender Diversity in the Music Industry

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Law School Student Scholarship Seton Hall Law 2019 Can't Hold Us Down”1: How to Use Inclusion Riders to Increase Gender Diversity in the Music Industry Laura Kozel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kozel, Laura, "Can't Hold Us Down”1: How to Use Inclusion Riders to Increase Gender Diversity in the Music Industry" (2019). Law School Student Scholarship. 1019. https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship/1019 ABSTRACT Despite improvements in female visibility and a number of movements pushing for equality in recent years, gender imbalance continues to plague the world of entertainment. While strides have been made to achieve parity in the film industry, little progress has been made to achieve the same in music where the disproportionality of females is even worse. Females are chronically underrepresented across virtually all aspects of music, both on-stage and off-stage, whether it be as musicians or as executives, which subsequently effects the amount of nominations, as well as awards that females in music receive. The implementation of inclusion riders in Hollywood has demonstrably improved female representation in popular films, but until now inclusion riders have not been applied to the music industry. This paper explores the application of inclusion riders to the music industry in order to remedy a long-standing history of female exclusion, as well as increase visibility for the vast number of talented females in the music industry that deserve the same opportunities and recognition, but until now have remained invisible. -

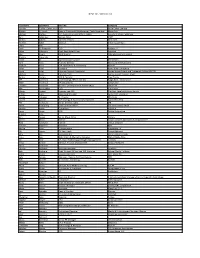

NYME 2017 Attendee List.Xlsx

NYME 2017 Attendee List First Name Last Name Job Title Company Tiombe "Tallie" Carter, Esq. CEO Tallie Carter Law Esq Wesley A'Harrah Head of Training & Development, Tools Reporting Music Ally Michael Abitbol SVP, Business & Legal Affairs, Digital Sony/ATV Music Publishing Dan Ackerman Section Editor CNET Andrea Adams Director of Sales FilmTrack Andrew Adler Director Citrin Cooperman Stella Ahn Turki Al Shabanah CEO Rotana TV Philip Alberstat Chief Operating Officer Contend Jake Alcorn MBA Student Columbia Business School Brianna Alexander Sarah Ali Operation and Support Streamlabs June Alian Publicity Director Skybound Entertainment Graham Allan EVP, Operations & Consulting KlarisIP Karen Allen President Karen Allen Consulting Susan Allen Attorney Advisor (Copyright) United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) Michele Amar Director / CEO Bureau Export / France Rocks Danny Anders CEO & Founder ClearTracks Jeff Anderson Chief Strategy Officer and GM Bingo Bash - GSN Games Mark Anderson VP Global Sales LumaForge Stephen Anderson Business Development & Partnerships Octane AI Alec Andronikov CEO The Visory Manny Anekal Founder and CEO The Next Level and Versus Sports Debbie Anjos Marketing Manager Gerber Life Insurance Farooq Ankalagi Sr. Director Mindtree Lauren Apolito SVP Strategy & Business Development Rumblefish/HFA Phil Ardizzone Senior Director, Sales IAB Mario Armstrong Chief Content Officer The Never Settle Show Kwadjo Asare Consultant FIGHTER Kwasi Asare CEO Fighter Interactive Nuryani Asari Jem Aswad Senior Music Editor Variety -

NEWSLETTER a N E N T E R T a I N M E N T I N D U S T R Y O R G a N I Z a T I On

October 2012 NEWSLETTER A n E n t e r t a i n m e n t I n d u s t r y O r g a n i z a t i on What does a music producer do, anyway? By Ian Shepherd The term ‘music producer’ means different things to different The President’s Corner people. Some are musicians, some are engineers, some are remixers. So what does a music producer actually do ? Big thanks tonight to Kent Liu and Michael Morris for putting together such an impressive panel of producers. In very pragmatic terms, the producer is a ‘project manager’ for As a reminder, we are able to provide & present this type the recording, mixing and mastering process. of dinner meeting because of our corporate and individual She has an overall vision for the music, the sound and the goals memberships, so please go to theccc.org today and renew of the project, and brings a unique perspective to inspire, assist your membership – we appreciate your support (and the and sometimes provoke the artists. membership pays for itself if you attend our meetings on a regular basis). See you in November!! The producer should make the record more than the sum of its parts – you could almost say she is trying to create musical alchemy. Eric Palmquist Every producer brings different skills and a different approach, President, California Copyright Conference. and this can make what they do difficult to summarize. In this post I’ve identified seven distinct types of record producer to try and make this clearer. -

Countrybreakout Radio Chart on March 19

March 19, 2021 The MusicRow Weekly Friday, March 19, 2021 Coming Soon: The 56th Academy of SIGN UP HERE (FREE!) Country Music Awards If you were forwarded this newsletter and would like to receive it, sign up here. THIS WEEK’S HEADLINES 56th annual ACM Awards Warner Chappell Music / Amped Entertainment Sign KK Johnson Jim Catino To Exit Sony Music Nashville NSAI Promotes Jennifer Turnbow To COO Jimmie Allen Renews With The 56th Academy of Country Music Awards are less than a month away. Endurance Music Group Honoring the biggest names and emerging talent in country music, the 56th ACM Awards will broadcast live from three iconic country music Samantha Borenstein venues: the Grand Ole Opry House, Nashville’s historic Ryman Auditorium Launches Management Firm and The Bluebird Cafe on Sunday, April 18 (8:00-11:00 PM, live ET/ delayed PT) on the CBS Television Network. Ross Copperman Signs With Photo Finish Records Voting for the 56th ACM Awards opened on March 17, and closes Wednesday, March 24. Tigirlily Signs With Monument Maren Morris and Chris Stapleton lead the nominations with six each. Records Stapleton, Luke Bryan, Eric Church, Luke Combs, and Thomas Rhett Miranda Lambert, Dan + are nominated for the top honor, Entertainer of the Year. Shay, John Prine Among Grammy Winners Reigning Entertainer of the Year Rhett has four nominations, including his second nomination for Entertainer of the Year. DISClaimer Singles Reviews Combs and Stapleton are both nominees for Entertainer of the Year. A win And much more… for either artist in that category will also clinch the coveted Triple Crown Award, which consists of an Entertainer of the Year win, plus wins in an act's respective New Artist (male, female, or duo or group) and Artist (male, female, duo or group) categories. -

Recording Academy Announces Harvey Mason Jr., Tammy Hurt, Terry Hemmings, and Christine Albert As Newly Elected National Officer

RECORDING ACADEMY™ ANNOUNCES HARVEY MASON JR., TAMMY HURT, TERRY HEMMINGS, AND CHRISTINE ALBERT AS NEWLY ELECTED NATIONAL OFFICERS SANTA MONICA, CALIF. (JUNE 6, 2019) — The Recording Academy™ announced today its newly elected National Officers of the Board of Trustees, voted upon at the organization's annual spring Board of Trustees meeting in May. Record producer Harvey Mason Jr. has been elected as the Chair of the Board of Trustees, and managing partner of Placement Music Tammy Hurt will serve as Vice Chair. Veteran music executive Terry Hemmings was re-elected Secretary/Treasurer and recording artist and founder/CEO of Swan Songs Christine Albert assumes the position of Chair Emeritus. All officer appointments were effective on June 1, 2019. "Following the outcome of our annual spring Board of Trustees meeting, it's clear the Recording Academy's governance continues to demonstrate its commitment to keeping the Academy a relevant and responsive organization," said Neil Portnow, President/CEO of the Recording Academy. "We are thrilled with the diversity and depth of music industry experience embodied by our new slate of National Officers. These esteemed and talented individuals will continue to carry out the mission of this organization which works on behalf of all music creators and professionals year-round." ABOUT THE NATIONAL OFFICERS Harvey Mason Jr. has penned and produced songs for both industry legends and today's biggest superstars. Everyone from Whitney Houston to Beyoncé, Elton John to Justin Timberlake, Aretha Franklin to Ariana Grande, Britney Spears to Camila Cabello, Luther Vandross to Justin Bieber, and Michael Jackson to Chris Brown have called on Mason to deliver uniquely musical, yet radio-friendly hit records. -

Ozymandias: Kings Without a Kingdom Kevin Kshitiz Bhatia

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Law School Student Scholarship Seton Hall Law 5-1-2014 Ozymandias: Kings Without a Kingdom Kevin Kshitiz Bhatia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship Recommended Citation Bhatia, Kevin Kshitiz, "Ozymandias: Kings Without a Kingdom" (2014). Law School Student Scholarship. 441. https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship/441 Ozymandias: Kings without a Kingdom Ozymandias is an English sonnet written by poet Percy Shelly in 1818. The sonnet reads: “I met a traveller from an antique land who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand, half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown, and wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, tell that its sculptor well those passions read which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, the hand that mocked them and the heart that fed: And on the pedestal these words appear: ’My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!’ Nothing beside remains. Round the decay of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare the lone and level sands stretch far away.”75 There are several conflicting accounts regarding Shelly’s inspiration for the sonnet, but the most widely accepted story tells that Percy Shelly was inspired by the arrival in Britain of a statute of the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II. Observing the irony of a pharaoh’s statute, which was created to glorify the omnipotence of the ruler, being carried into port as a mere collectible in a museum, Shelly wrote the sonnet to summarize a particular irony that presents itself repeatedly throughout history. -

Songwriter Music Executive Contact

Multi-Award Winning Songwriter, Producer, Publisher, NSAI Board Member,and Music Jeff Cohen Industry Executive based in Nashville and New York City Songwriter Cuts Crazy For This Girl - Evan and Jaron (Top 3 Billboard Hit) Postcard From Paris - The Band Perry (Top 5 Billboard Hit) Holy Water - Big and Rich (Top 15 Billboard Hit, #1 Video CMT and GAC) Giddy On Up - Laura Bell Bundy (Top 20 Billboard Hit, #1 Video CMT and GAC) I Turn To You - Richie McDonald (Lonestar) (Top 5 Billboard Hit) Endless Road - Worry Dolls (Song of The Year Nominee, UK Americana Awards) Songs also recorded by Sugarland, Josh Groban, Macy Gray, Sandi Patty, Spin Doctors, Nick Lachey, Mandy Moore, Marc Broussard, Jasmine Murray and many more… International Cuts The Shires, Nikhil D’Souza, Ilse Delange, Cho Yong-Pil, Teitur, Hanne Sorvaag, Doc Walker, Luz Casal, Tina Dico, Hush and more… Movies Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, My Super Ex-Girlfriend, Stuart Little 2, Aquamarine, Princess Diaries, Grandma's Boy and more… TV Jack And Jill (WB - Theme) The Exes - (Nickelodeon - Theme) Paw Patrol - (Nickelodeon - Theme) I Married A Princess - (Lifetime - Theme) Dawson's Creek, One Tree Hill, Party Of Five, Desperate Housewives, The Simpsons, Saturday Night Live, The Apprentice, Ed, Couples Therapy, and many more… Co-Writers Kara DioGuardi Kelsea Ballerini Delta Goodrum Sacha Skarbek Kimberly Perry James Slater Mike Elizondo John Rich JT Harding Jamie Scott Big Kenny Mitch Allan Liz Rose Bob DiPiero Ross Copperman Lori McKenna Rodney Clawson Jamie Hartman Kristian Bush Tom Douglas Sara Evans Jennifer Nettles Matraca Berg Paul Overstreet and many more… Music Executive BMI - Senior Director, New York Office Warner/Chappell Music - Director, New York Office Signed And Worked With Artists Such As: Jeff Buckley Joan Osborne Kara DioGuardi Spin Doctors Blues Traveler Ben Folds Lisa Loeb Ani DiFranco Uncle Tupelo/Wilco Contact Jeff Cohen: [email protected] soundcloud.com/panchoslament. -

Feminism: When the Label 'White' Gets Attached in Pop Music Industry

Feminism: When the Label ‘White’ Gets Attached in Pop Music Industry Audrey Lee and Brian Oh Published 5 Oct 2020 Abstract This paper describes a qualitative study that investigates the pop music genre starting from the 2000s, relating it to feminism. The investigation focuses on understanding when female artists are considered feminist, and when the label ‘white feminist’ is applied to specific female artists. Based on media press and public perspective, the research hopes to find key characteristics that separates the moment when the label feminism and white feminism are applied, especially in relation to other attributes such as gender orientation, sexual orientation, and race. The purpose of the research is to provide more insight into understanding feminism in the context of today, and to how navigate complex spaces such as media image and personal identity, labels that come with the public status of their profession. 1 Introduction MTV, The GRAMMYs, Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube, KIIS FM - Popular music aka ‘Pop Music’ is an industry that is in a constant flurry of activity and publicity, through television, radio, news, and videos. When referencing popular music, the paper is defining Pop Music as any popular music produced after the 2000s. With such a public identity, artists in the pop music industry are expected to navigate the complexities of the business that exist, including image, policies, and activism. In the current generation where technology and communication can occur in an instant, female artists are expected to adjust to a multi-faceted industry that, at many times, can seem paradoxical in nature. Many female artists are forced to find the right balance between outgoing and timid when portraying their public personas. -

Antonio “La” Reid

ICON words DOMINIQUE CARSON L.A. Reid has many titles under his belt: musician, songwriter, record producer, music executive, former music judge, and now chairman and CEO of Epic Records. The entertainment industry undeniably recognizes his contributions in music, business, and entrepreneurship. The Grammy Award- winning executive has mentored some of the biggest names in music including P!nk, TLC, Toni Braxton, Mariah Carey, Usher, Donnell Jones, and Outkast. His work is commended because he understands the importance of being business ANTONIO savvy, turning a prospective artist’s dream into a reality, and composing and recording material that will leave the world stunned. L.A Reid turned his life- long passion of music into a business empire emulated by aspiring business men. But achievements didn’t come automatically--he took risks, embraced his humble beginnings as an artist, believed in his former record label, and wasn’t afraid of “LA” REID change and the process of evolution. Reid’s musical debut began when he was a member of the R&B band, The Deele, which also included Kenneth “Babyface” Edmonds. The group recorded their groundbreaking hit, “Two Occasions” in the 1980s. Even though the group disbanded before the single was released, it is still considered one of the greatest R&B tracks of all time. The group performs the single occasionally at concerts because it will always be a Top 10 hit for listeners. Fans can sing the lyrics to a significant other when trying to reconcile. After his stint in Deele ended, Reid launched LaFace Records with Babyface in Atlanta, Georgia in 1989. -

Build a Pop Star!!!!!

BUILD A POP STAR!!!!! You are an assistant to a famous music talent scout/executive named Miss Daly. Daly Records discovers, produces, markets, and creates pop stars from any genre of music, from Rap to Classical. These 10 hopeful pop stars have submitted audition videos to your company. Miss Daly is very busy and has tasked you with picking, developing, and marketing the company’s next pop star. After watching each audition, choose the one person who you would like to develop into a pop star. Write a one to two-page memo to your boss as to why this artist has caught your attention and ears, the target audience to whom you will market this new pop star, and a brief proposed schedule/timeline of when the artist will be ready to market. Consider some of the following questions when deciding how long it will take to develop your artist and make him/her ready for marketing: Will you need to create a new name/stage moniker for the artist? Will the artist need anything changed about him/her physically? Will the artist need dancing/vocal/stage coaching? How much money will it cost the company to market the star to the public? Next, create a playlist on YouTube of five tracks for their first demo LP. Although you will be picking songs that have already been made famous by other pop stars, choose tracks that you think would best demonstrate your artist’s voice and style, and reach your pop star’s targeted audience. Write a short, two to three sentence blurb for each track that explains why you chose that song. -

The Evolution of the Music Industry in the Post-Internet

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2012 The volutE ion of the Music Industry in the Post- Internet Era Ashraf El Gamal Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation El Gamal, Ashraf, "The vE olution of the Music Industry in the Post-Internet Era" (2012). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 532. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/532 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT MCKENNA COLLEGE The Evolution of the Music Industry in the Post-Internet Era SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR JANET SMITH AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ASHRAF EL GAMAL FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL 2012 DECEMBER 3, 2012 - 2 - Abstract: The rise in the prevalence of the Internet has had a wide range of implications in nearly every industry. Within the music business, the turn of the millennium came with a unique, and difficult, set of challenges. While the majority of academic literature in the area focuses specifically on the aspect of file sharing within the Internet as it negatively impacts sales within the recording sector, this study aims to assess the Internet’s wider impacts on the broader music industry. In the same time that record sales have plummeted, the live music sector has thrived, potentially presenting alternative business models and opportunities. This paper will discuss a variety of recent Internet-related developments including the rise of legal digital distribution, key economic implications, general welfare effects, changes in consumer preference and social phenomena as they relate to both the recording and live entertainment sectors.