Copyright by Caroline Booth Pinkston 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CLEVELAN ORCHESTRA California Masterwor S

����������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������������������������������������� �������� ������������������������������� ��������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ����������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������������ ���������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������� ������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������� ������������� ������ ������������� ��������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� ����������� �������������������������������� ����������������� ����� �������� �������������� ��������� ���������������������� Welcome to the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Orchestra’s performances in the museum California Masterworks – Program 1 in May 2011 were a milestone event and, according to the Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland Museum of Art Plain Dealer, among the year’s “high notes” in classical Wednesday evening, May 1, 2013, at 7:30 p.m. music. We are delighted to once again welcome The James Feddeck, conductor Cleveland Orchestra to the Cleveland Museum of Art as this groundbreaking collaboration between two of HENRY COWELL Sinfonietta -

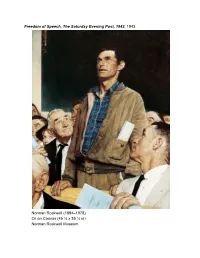

2-A Rockwell Freedom of Speech

Freedom of Speech, The Saturday Evening Post, 1943, 1943 Norman Rockwell (1894–1978) Oil on Canvas (45 ¾ x 35 ½ in) Norman Rockwell Museum NORMAN ROCKWELL [1894–1978] 19 a Freedom of Speech, The Saturday Evening Post, 1943 After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, What is uncontested is that his renditions were not only vital to America was soon bustling to marshal its forces on the home the war effort, but have become enshrined in American culture. front as well as abroad. Norman Rockwell, already well known Painting the Four Freedoms was important to Rockwell for as an illustrator for one of the country’s most popular maga- more than patriotic reasons. He hoped one of them would zines, The Saturday Evening Post, had created the affable, gangly become his statement as an artist. Rockwell had been born into character of Willie Gillis for the magazine’s cover, and Post read- a world in which painters crossed easily from the commercial ers eagerly followed Willie as he developed from boy to man world to that of the gallery, as Winslow Homer had done during the tenure of his imaginary military service. Rockwell (see 9-A). By the 1940s, however, a division had emerged considered himself the heir of the great illustrators who left their between the fine arts and the work for hire that Rockwell pro- mark during World War I, and, like them, he wanted to con- duced. The detailed, homespun images he employed to reach tribute something substantial to his country. a mass audience were not appealing to an art community that A critical component of the World War II war effort was the now lionized intellectual and abstract works. -

Barnard College Bulletin 2017-18 3

English .................................................................................... 201 TABLE OF CONTENTS Environmental Biology ........................................................... 221 Barnard College ........................................................................................ 2 Environmental Science .......................................................... 226 Message from the President ............................................................ 2 European Studies ................................................................... 234 The College ........................................................................................ 2 Film Studies ........................................................................... 238 Admissions ........................................................................................ 4 First-Year Writing ................................................................... 242 Financial Information ........................................................................ 6 First-Year Seminar ................................................................. 244 Financial Aid ...................................................................................... 6 French ..................................................................................... 253 Academic Policies & Procedures ..................................................... 6 German ................................................................................... 259 Enrollment Confirmation ........................................................... -

Download on to Your Computer Or Device

Underwood New Music Readings American Composers Orchestra PARTICIPATING COMPOSERS Andy Akiho Andy Akiho is a contemporary composer whose interests run from steel pan to traditional classical music. Recent engagements include commissioned premieres by the New York Philharmonic and Carnegie Hall’s Ensemble ACJW, a performance with the LA Philharmonic, and three shows at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC featuring original works. His rhythmic compositions continue to increase in recognition with recent awards including the 2014-15 Luciano Berio Rome Prize, a 2012 Chamber Music America Grant with Sybarite5, the 2011 Finale & ensemble eighth blackbird National Composition Competition Grand Prize, the 2012 Carlsbad Composer Competition Commission for Calder Quartet, the 2011 Woods Chandler Memorial Prize (Yale School of Music), a 2011 Music Alumni Award (YSM), the 2010 Horatio Parker Award (YSM), three ASCAP Plus Awards, an ASCAP Morton Gould Young Composers Award, and a 2008 Brian M. Israel Prize. His compositions have been featured on PBS’s “News Hour with Jim Lehrer” and by organizations such as Bang on a Can, American Composers Forum, and The Society for New Music. A graduate of the University of South Carolina (BM, performance), the Manhattan School of Music (MM, contemporary performance), and the Yale School of Music (MM, composition), Akiho is currently pursuing a Ph.D. at Princeton University. In addition to attending the 2013 International Heidelberger Frühling, the 2011 Aspen Summer Music Festival, and the 2008 Bang on a Can Summer Festival as a composition fellow, Akiho was the composer in residence for the 2013 Chamber Music Northwest Festival and the 2012 Silicon Valley Music Festival. -

2018 Annual Report Alfred P

2018 Annual Report Alfred P. Sloan Foundation $ 2018 Annual Report Contents Preface II Mission Statement III From the President IV The Year in Discovery VI About the Grants Listing 1 2018 Grants by Program 2 2018 Financial Review 101 Audited Financial Statements and Schedules 103 Board of Trustees 133 Officers and Staff 134 Index of 2018 Grant Recipients 135 Cover: The Sloan Foundation Telescope at Apache Point Observatory, New Mexico as it appeared in May 1998, when it achieved first light as the primary instrument of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. An early set of images is shown superimposed on the sky behind it. (CREDIT: DAN LONG, APACHE POINT OBSERVATORY) I Alfred P. Sloan Foundation $ 2018 Annual Report Preface The ALFRED P. SLOAN FOUNDATION administers a private fund for the benefit of the public. It accordingly recognizes the responsibility of making periodic reports to the public on the management of this fund. The Foundation therefore submits this public report for the year 2018. II Alfred P. Sloan Foundation $ 2018 Annual Report Mission Statement The ALFRED P. SLOAN FOUNDATION makes grants primarily to support original research and education related to science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and economics. The Foundation believes that these fields—and the scholars and practitioners who work in them—are chief drivers of the nation’s health and prosperity. The Foundation also believes that a reasoned, systematic understanding of the forces of nature and society, when applied inventively and wisely, can lead to a better world for all. III Alfred P. Sloan Foundation $ 2018 Annual Report From the President ADAM F. -

Humanitarian Affairs Theory, Case Studies And

HUST 4501: Humanitarian Affairs: Foreign Service Program Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs Fordham University – Summer Session II Monday – Thursday, 1:00 PM – 4:00 PM Lincoln Center – Classroom 404 INSTRUCTOR INFORMATION Instructor: Dan Gwinnell Email: [email protected] Tel: +1 908-868-6489 Office hours: By appointment – but I am very flexible and will always be happy to make time to meet with you! COURSE OVERVIEW The Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs (IIHA) prepares current and future aid workers with the knowledge and skills needed to respond effectively in times of humanitarian crisis and disaster. Our courses are borne of an interdisciplinary curriculum that combines academic theory with the practical experience of humanitarian professionals. The Humanitarian Studies program is multi-disciplinary and draws on a variety of academic and intellectual frameworks to examine and critique the international community’s response to situations of emergency, disaster and development. There is a natural tension in humanitarian studies between the practical implementation of humanitarian initiatives related to disaster or development; and, on the other hand, more introspective and academic attempts to understand and critique the effectiveness of these initiatives. Understanding how to effectively navigate this tension between theory and practice is at the heart of Fordham’s undergraduate program in humanitarian studies, and will serve as a guiding theme of this class. Throughout the course, we will work to try and form a coherent set of opinions on a) whether humanitarian action is a positive and necessary component of our global landscape, and b) if so, how our theory can guide our practice to help improve the efficiency and outcomes of humanitarian endeavors. -

Baloo's Bugle

BALOO'S BUGLE Volume 24, Number 6 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- “If you want children to keep their feet on the ground, put some responsibility on their shoulders.” Abigail Van Buren --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- January 2018 Cub Scout Roundtable February 2018 Program Ideas CHEERFUL / ABRACADABRA 2017-2018 CS Roundtable Planning Guide –No themes or month specified material PART I – MONTHLY FUN STUFF 12 ways to celebrate Scout Sunday, Scout Sabbath and/or Scout Jumuah: • Wear your Scout uniform to worship services. • Present religious emblems to Scouts, & leaders who have earned them in the past year. • Recruit several Scouts or Scouters to read passages from religious text. • Involve uniformed Scouts as greeters, ushers, gift bearers or the color guard. • Invite a Scout or Scouter to serve as a guest speaker or deliver the sermon. • Hold an Eagle Scout court of honor during the worship service. • Host a pancake breakfast before, between or after SCOUT SUNDAY / services. SABBATH / JUMUAH • Collect food for a local food pantry. • Light a series of 12 candles while briefly explaining the points of the Scout Law. • Show a video or photo slideshow of highlights from the pack, troop, crew or ship’s past year. • Bake (or buy) doughnuts to share before services. • Make a soft recruiting play by setting up a table Is your Pack planning a Scout Sunday, Scout Shabbat, near the entrance to answer questions about your or Scout Jumuah this year?? Scout unit. You should consider doing so - For more information, checkout – ✓ Scout Sunday – February 4 ✓ Scout Shabbat -Sundown to Sundown, February 9 to 10 ✓ Scout Jumuah – February 9 https://blog.scoutingmagazine.org BALOO'S BUGLE – (Part I – Monthly Fun Stuff – Jan 2018 RT, Feb 2018 Program) Page 2 PHILMONT CS RT TABLE OF CONTENTS SUPPLEMENT SCOUT SUNDAY / SABBATH / JUMUAH ............ -

News in Brief

C olumbia U niversity RECORD June 11, 2004 3 News in Brief Queen Elizabeth II Honors that capture key elements of the real cir- culatory system, which could be used for Marconi’s John Jay Iselin improved diagnostic nuclear magnetic CU Receives Two Grants for Digital Projects resonance imaging and hydrodynamic tar- From National Endowment for the Humanities geting of drug delivery. he National Endowment for the Humanities recently made two grants to Colum- Bill Berkeley Named Tbia. The Columbia University Libraries has been awarded a $300,000 grant from 2004 Carnegie Scholar the NEH to continue the development of Digital Scriptorium, a collaborative online project that digitizes and catalogs medieval and Renaissance manuscripts from insti- ill Berkeley, Columbia adjunct pro- tutions across the United States. Under the two-year grant, the online project will Bfessor of international affairs, was move from its current home at the University of California, Berkeley, to Columbia. recently named a 2004 Carnegie Scholar, Jean Ashton, director of the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, is the principal inves- joining a total of 52 others awarded the tigator on the grant; Consuelo Dutschke, Columbia’s curator of medieval and Renais- fellowship since 2000. The 15 scholars sance manuscripts, was one of the founders of the project and is serving as the man- chosen this year will explore such issues aging director. as economic growth and human develop- Digital Scriptorium is an ment; the rise of far-right extremist image database of medieval and groups and the role masculinity plays in Renaissance manuscripts that their resurgence; and how U.S. -

ADA Fluoridation Facts 2018

Fluoridation Facts Dedication This 2018 edition of Fluoridation Facts is dedicated to Dr. Ernest Newbrun, respected researcher, esteemed educator, inspiring mentor and tireless advocate for community water fluoridation. About Fluoridation Facts Fluoridation Facts contains answers to frequently asked questions regarding community water fluoridation. A number of these questions are responses to myths and misconceptions advanced by a small faction opposed to water fluoridation. The answers to the questions that appear in Fluoridation Facts are based on generally accepted, peer-reviewed, scientific evidence. They are offered to assist policy makers and the general public in making informed decisions. The answers are supported by over 400 credible scientific articles, as referenced within the document. It is hoped that decision makers will make sound choices based on this body of generally accepted, peer-reviewed science. Acknowledgments This publication was developed by the National Fluoridation Advisory Committee (NFAC) of the American Dental Association (ADA) Council on Advocacy for Access and Prevention (CAAP). NFAC members participating in the development of the publication included Valerie Peckosh, DMD, chair; Robert Crawford, DDS; Jay Kumar, DDS, MPH; Steven Levy, DDS, MPH; E. Angeles Martinez Mier, DDS, MSD, PhD; Howard Pollick, BDS, MPH; Brittany Seymour, DDS, MPH and Leon Stanislav, DDS. Principal CAAP staff contributions to this edition of Fluoridation Facts were made by: Jane S. McGinley, RDH, MBA, Manager, Fluoridation and Preventive Health Activities; Sharon (Sharee) R. Clough, RDH, MS Ed Manager, Preventive Health Activities and Carlos Jones, Coordinator, Action for Dental Health. Other significant staff contributors included Paul O’Connor, Senior Legislative Liaison, Department of State Government Affairs. -

Honoring America's Spirit

September 2017 Vol. 5, Number 6 Gazette Dedicated to John Knox Village Inform, Inspire, Involve A Life Plan Continuing Care Retirement Community Published Monthly by John Knox Village, 651 S.W. Sixth Street, Pompano Beach, Florida 33060 IN THIS MONTH’S ISSUE Honoring America’s Spirit Chef Mark’s Recipe That Can’t Be Beet ................ 3 The Artistic Genius Of Norman Perceval Rockwell he ex- Nona Smith Gazette Contributor Ttraordi- nary oeuvre of Norman Rockwell deserves a second look, as his work reflects many of the concerns we have today: The threat of war, tough economic times, cul- tural, social and racial divides, and reveals the true genius of one of the most extraordinary American artists of his time. Looking at Rockwell’s Rockwell Memories ........ 3 extensive collection of drawings, paintings and sketches shows his Visit Us In September .... 5 compositional brilliance, his acuity as a story teller and his celebrated Crossword Puzzle ......... 5 ability to bring people to life through paint, paper and canvas. Autumn Sales Event ....... 6 The Early Years South Florida Events, Born Norman Percevel Rockwell Shows & Arts .................. 8 in New York City in 1894, Rock- well had an innate artistic talent. Golden Anniversary ..... 8 By the age of 14, all he wanted The Psychiatrist Is In ..... 9 was to be an artist. At 16, his focus was so intent on his art, that he dropped out of high school and enrolled at the National Academy of Design. He later transferred to the prestigious Art Students League of New York where he studied with Thomas Fogarty for illustra- “Triple Self-Portrait,” by Norman Rockwell, 1960. -

OJAI at BERKELEY VIJAY IYER, Music DIRECTOR

OJAI AT BERKELEY VIJAY IYER, MusIC DIRECTOR The four programs presented in Berkeley this month mark the seventh year of artistic partnership between the Ojai Music Festival and Cal Performances and represent the combined efforts of two great arts organizations committed to innovative and adventur- ous programming. The New York Times observes, “There’s prob- ably no frame wide enough to encompass the creative output of the pianist Vijay Iyer.” Iyer has released 20 albums covering remarkably diverse terrain, most recently for the ECM label. The latest include A Cosmic Rhythm with Each Stroke (2016), a collaboration with Iyer’s “hero, friend, and teacher,” Wadada Leo smith; Break Stuff (2015), featuring the Vijay Iyer Trio; Mutations (2014), featuring Iyer’s music for piano, string quartet, and electronics; and RADHE RADHE: Rites of Holi (2014), the score to a film by Prashant Bhargava, performed with the renowned International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE). The Vijay Iyer Trio (Iyer, stephan Crump on bass, and Marcus Gilmore on drums) made its name with two acclaimed and influential albums. Acceler ando (2012) was named Jazz Album of the Year in three separate critics polls, by the Los Angeles Times, Amazon.com, and NPR. Hailed by PopMatters as “the best band in jazz,” the trio was named 2015 Jazz Group of the Year in the DownBeat poll, with Vijay Iyer (music director), the Grammy- Iyer having earlier received an unprecedented nominated composer-pianist, was described “quintuple crown” in their 2012 poll (Jazz by Pitchfork as “one of the most interesting Artist of the Year, Pianist of the Year, Jazz and vital young pianists in jazz today,” by the Album of the Year, Jazz Group of the Year, and LA Weekly as “a boundless and deeply impor- Rising star Composer). -

National Endowment for the Humanities Grant Awards and Offers, August 2018

OFFICE OF COMMUNICATIONS NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES GRANT AWARDS AND OFFERS, AUGUST 2018 ALABAMA (2) $503,645 Birmingham Alabama Humanities Foundation Outright: $178,871 [Institutes for School Teachers] Project Director: Martha Bouyer Project Title: “Stony the Road We Trod . .”: Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy Project Description: A three-week institute for 30 school teachers on the history and legacy of the civil rights movement in Alabama. Tuscaloosa University of Alabama Outright: $324,774 [National Digital Newspaper Program] Project Director: Lorraine Madway Project Title: Alabama Digital Newspaper Project Project Description: Digitization of 100,000 pages of Alabama newspapers published between 1813 and 1922 as part of the state’s participation in the National Digital Newspaper Program. ALASKA (2) $1,057,000 Juneau Alaska Division of Libraries, Archives, and Museums Outright: $307,000 [National Digital Newspaper Program] Project Director: Anastasia Tarmann Project Title: Alaska Digital Newspaper Project Project Description: Digitization of 100,000 pages of Alaska newspapers published prior to 1963, as part of the state’s participation in the National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP). Juneau Arts and Humanities Council Match: $750,000 [Infrastructure and Capacity-Building Challenge Grants] Project Director: Nancy DeCherney Project Title: The New Juneau Arts and Culture Center: Strengthening the Humanities in Alaska Project Project Description: Construction of a new Juneau Arts and Culture Center in downtown Juneau, Alaska. NEH Grant Offers and Awards, August 2018 Page 2 of 39 ARIZONA (6) $1,116,585 Scottsdale Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Match: $176,106 [Infrastructure and Capacity-Building Challenge Grants] Project Director: Fred Prozzillo Project Title: Taliesin West Accessibility and Infrastructure Improvements Project Description: A project to support accessibility upgrades and theater renovations to Taliesin West, Frank Lloyd Wright’s winter home and studio from 1937 until his death in 1959.