The Art Critic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“American Chronicles: the Art of Norman Rockwell at TAM” Published in Artdish, March 2011 2011 Jane Richlovsky

“American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell at TAM” published in Artdish, March 2011 2011 Jane Richlovsky Norman Rockwell's painting "Discovery", currently on display at the Tacoma Art Museum, depicts a pajama-clad young boy finding a Santa Claus suit and false beard in Dad's bureau drawer, incriminating evidence of the old man's fakery. The picture appeared on the cover of the December 29, 1956 Saturday Evening Post. It's hard at first to get past the boy's facial expression. His eyes are popping out of his head, in a way that irritatingly foreshadows the ubiquitous Macauley Caulkin "Home Alone" publicity shot. However unfortunate this association, the expression is so utterly unconvincing as a portrayal of having one's cherished mythology punctured, that one can't help but think the kid never believed in Santa in the first place. Considering that this is one of many Rockwell paintings that repeatedly revisit the Santa-unmasking narrative over decades, you have to wonder: Is the guy responsible for our vision of the American Myth perhaps telling us we shouldn't be so surprised or upset that it's all made up? I've always found sunny, idealized, 1950's-style Leave-it-to-Beaver archetypal America intriguing, compelling, and horrifying. I'm far from alone in this, but I have spent more time than most people immersed in its ephemera, interrogating, digesting, cutting up, reconfiguring, and spitting back out endless images from midcentury domestic magazines. Imagine my shock when, after all that, putting together a show of the resulting paintings, I encounter a dealer's misbegotten press release, or an enthusiastic patron, praising what I thought was my scathing critique as a fond, nostalgic look back at a "simpler time". -

Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg

Smithsonian American Art Museum TEACHER’S GUIDE from the collections of GEORGE LUCAS and STEVEN SPIELBERG 1 ABOUT THIS RESOURCE PLANNING YOUR TRIP TO THE MUSEUM This teacher’s guide was developed to accompany the exhibition Telling The Smithsonian American Art Museum is located at 8th and G Streets, NW, Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and above the Gallery Place Metro stop and near the Verizon Center. The museum Steven Spielberg, on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in is open from 11:30 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. Admission is free. Washington, D.C., from July 2, 2010 through January 2, 2011. The show Visit the exhibition online at http://AmericanArt.si.edu/rockwell explores the connections between Norman Rockwell’s iconic images of American life and the movies. Two of America’s best-known modern GUIDED SCHOOL TOURS filmmakers—George Lucas and Steven Spielberg—recognized a kindred Tours of the exhibition with American Art Museum docents are available spirit in Rockwell and formed in-depth collections of his work. Tuesday through Friday from 10:00 a.m. to 11:30 a.m., September through Rockwell was a masterful storyteller who could distill a narrative into December. To schedule a tour contact the tour scheduler at (202) 633-8550 a single moment. His images contain characters, settings, and situations that or [email protected]. viewers recognize immediately. However, he devised his compositional The docent will contact you in advance of your visit. Please let the details in a painstaking process. Rockwell selected locations, lit sets, chose docent know if you would like to use materials from this guide or any you props and costumes, and directed his models in much the same way that design yourself during the visit. -

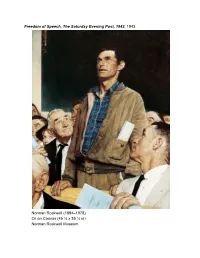

2-A Rockwell Freedom of Speech

Freedom of Speech, The Saturday Evening Post, 1943, 1943 Norman Rockwell (1894–1978) Oil on Canvas (45 ¾ x 35 ½ in) Norman Rockwell Museum NORMAN ROCKWELL [1894–1978] 19 a Freedom of Speech, The Saturday Evening Post, 1943 After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, What is uncontested is that his renditions were not only vital to America was soon bustling to marshal its forces on the home the war effort, but have become enshrined in American culture. front as well as abroad. Norman Rockwell, already well known Painting the Four Freedoms was important to Rockwell for as an illustrator for one of the country’s most popular maga- more than patriotic reasons. He hoped one of them would zines, The Saturday Evening Post, had created the affable, gangly become his statement as an artist. Rockwell had been born into character of Willie Gillis for the magazine’s cover, and Post read- a world in which painters crossed easily from the commercial ers eagerly followed Willie as he developed from boy to man world to that of the gallery, as Winslow Homer had done during the tenure of his imaginary military service. Rockwell (see 9-A). By the 1940s, however, a division had emerged considered himself the heir of the great illustrators who left their between the fine arts and the work for hire that Rockwell pro- mark during World War I, and, like them, he wanted to con- duced. The detailed, homespun images he employed to reach tribute something substantial to his country. a mass audience were not appealing to an art community that A critical component of the World War II war effort was the now lionized intellectual and abstract works. -

BAM 50 State Initiative Art Project—A Partnership with for Freedoms—Activates Civic Engagement Through Art Work Creation, Saturday, Oct 20

BAM 50 State Initiative Art Project—a partnership with For Freedoms—activates civic engagement through art work creation, Saturday, Oct 20 Free public event will be led by Brooklyn visual artist Katherine Toukhy Oct 5, 2018/Brooklyn, NY—The Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) has partnered with For Freedoms in an afternoon of civic engagement on Saturday, Oct 20 from 1–3pm at the South Site Plaza (Lafayette Ave, corner of Flatbush Ave). Attendees will participate in an art-making project, led by Brooklyn visual artist Katherine Toukhy, to create and share social and political statements with the community. Images of finished artworks will be photographed and displayed on BAM’s outdoor digital signpost on the corner of Flatbush Ave and Lafayette Ave—running on a loop until the mid-term elections in November. BAM’s VP of Education and Community Engagement Coco Killingsworth said, “We’re excited to join with For Freedoms and Katherine Toukhy in gathering community members for this creative civic activation. We hope this event inspires all of us to use our voices to engage in the democratic process.” For Freedoms started in 2016 as a platform for civic engagement, discourse, and direct action for artists in the United States. Inspired by Norman Rockwell’s 1943 painting of the four universal freedoms articulated by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1941—freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear—For Freedoms seeks to use art to deepen public discussions of civic issues and core values, and to clarify that citizenship in American society is deepened by participation, not by ideology. -

REVISITING the FOUR FREEDOMS by Donald M

EXCLUSIVE MCUF FEATURE REVISITING THE FOUR FREEDOMS By Donald M. Bishop PHOTO: The Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, located on an island in New York's East River, opened in 2012 3 • MARINE CORPS UNIVERSITY FOUNDATION • SUMMER 2019 EXCLUSIVE MCUF FEATURE Modern political warfare now includes both cyber and information operations. At MCU, Bren Chair of Strategic Communications Donald Bishop focuses his teaching and presentations on the “information” or “influence” dimension of conflict – disinformation, propaganda, persuasion, hybrid warfare – now enabled by the internet and social media. And he emphasizes that Americans, as they confront violent extremism and other threats, must know and be confident of the American values they defend. "Thanks, Grandpa, for coming to my game." Why look back at The Four Freedoms? First, in my classes at Marine Corps University, I’ve discovered that the current "I enjoyed it too, Jack. We men in our eighties don't get generation of Marines have never heard of them. Of Norman out as often as we wish. Seeing you score a run was Rockwell’s four famous paintings, they have seen only one – something. But you know, I noticed something else today. the family at Thanksgiving – and they don’t know they were "When you were at the plate, it carried me back to part of a series. Second – when Americans must articulate watching my older brother in the batter's box. You held the “what we’re for” (rather than “what we’re against”) – whether bat like he did. You have the same stance and the same in the war on terrorism or in a future of great power competi- swing. -

Two Concepts of Liberty

“No chains around my feet, but I’m not free.” – Bob Marley (Concrete Jungle) Two Concepts of Liberty 1. Positive vs Negative Liberty: Isaiah Berlin’s highly influential article brought to light the nature of the disagreement about political freedom. Largely until his time, the default assumption was that ‘liberty’ referred to what Berlin calls ‘negative liberty’. Negative Liberty: Roughly, freedom FROM. One is free in this sense to the extent that their actions are not hindered or prevented by outside interferers. Jefferson & Madison: This is, for instance, how the founding fathers understood liberty. Consider our constitutionally recognized rights of freedom of speech, freedom of religion (in James Madison’s Bill of Rights), and rights to life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness (in Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence). Example: Freedom of Speech: Having this right means that the government will not interfere with your speech (e.g., they will not pass laws forbidding you from saying whatever you want, and they will pass laws forbidding others from coercively preventing you from saying whatever you want, etc.). The same can be said for all of the others I listed. (For instance, as one more example, the government will allow you to pursue happiness, and they will not interfere with you or try to prevent you from doing so.) But, negative liberty of, say freedom of speech, doesn’t do me any good if I lack the ability to speak. For instance, imagine that I was raised by wolves and I don’t know how to speak any human languages, or read, or write, etc. -

THE VISUAL ARTS of LINDA VALLEJO: Indigenous Spirituality, Indigenist Sensibility, and Emplacement

THE VISUAL ARTS OF LINDA VALLEJO: Indigenous Spirituality, Indigenist Sensibility, and Emplacement Karen Mary Davalos Analyzing nearly forty years of art by Linda Vallejo, this article argues that her indigenist sensibility and indigenous spirituality create the aesthetics of disruption and continuity. In turn this entwined aesthetics generates emplacement, a praxis that resists or remedies the injuries of colonialism, patriarchy, and other systems of oppression that displace and disavow indigenous, Mexican, and Chicana/o populations in the Americas. Her visual art fits squarely within the trajectory of Chicana feminist decolonial practice, particularly in its empowerment of indigenous communities, Mexicans, and Chicana/os in the hemisphere. Key Words: Emplacement, hemispheric studies, aesthetic practice, spiritual mestizaje, decolonial imaginary, indigenous epistemology. Born in Los Angeles and raised by three generations of Mexican- heritage women, Linda Vallejo creates an oeuvre that is easy to understand as feminist and indigenist. Ancestral women, including three great-grandmothers, grandmothers, her mother, and several great aunts, were the artist’s first sources of feminist and indigenous knowledge. Vallejo describes one great- grandmother as “una indígena” because she was short, had dark skin, and wore trenzas and huaraches; she was also very strong, even fierce, having worked in the fields as she migrated north (Vallejo 2013).1 The appellation indicates the way in which Vallejo understands knowledge and subjectivity as emerging from material conditions, social forces, and affect, rather than biology. Vallejo is also a world traveler. Because of her father’s military service, she visited “all the major museums of Europe, many of them as a very young girl” (Vallejo 2013). -

A History of Global Governance

2 A History of Global Governance It is the sense of Congress that it should be a fundamental objective of the foreign policy of the United States to support and strengthen the United Nations and to seek its development into a world federation open to all nations with definite and limited powers adequate to preserve peace and prevent aggression through the enactment, interpretation and enforcement of world law. House Concurrent Resolution 64, 1949, with 111 co-sponsors There are causes, but only a very few, for which it is worthwhile to fight; but whatever the cause, and however justifiable the war, war brings about such great evils that it is of immense importance to find ways short of war in which the things worth fighting for can be secured. I think it is worthwhile to fight to prevent England and America being conquered by the Nazis, but it would be far better if this end could be secured without war. For this, two things are necessary. First, the creation of an international government, possessing a monopoly of armed force, and guaranteeing freedom from aggression to every country; second, that wars (other than civil wars) are justified when, and only when, they are fought in defense of the international law established by the international authority. Wars will cease when, and only when, it becomes evident beyond reasonable doubt that in any war the aggressor will be defeated. 1 Bertrand Russell, “The Future of Pacifism” By the end of the 20th century, if not well before, humankind had come to accept the need for and the importance of various national institutions to secure political stability and economic prosperity. -

Baloo's Bugle

BALOO'S BUGLE Volume 24, Number 6 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- “If you want children to keep their feet on the ground, put some responsibility on their shoulders.” Abigail Van Buren --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- January 2018 Cub Scout Roundtable February 2018 Program Ideas CHEERFUL / ABRACADABRA 2017-2018 CS Roundtable Planning Guide –No themes or month specified material PART I – MONTHLY FUN STUFF 12 ways to celebrate Scout Sunday, Scout Sabbath and/or Scout Jumuah: • Wear your Scout uniform to worship services. • Present religious emblems to Scouts, & leaders who have earned them in the past year. • Recruit several Scouts or Scouters to read passages from religious text. • Involve uniformed Scouts as greeters, ushers, gift bearers or the color guard. • Invite a Scout or Scouter to serve as a guest speaker or deliver the sermon. • Hold an Eagle Scout court of honor during the worship service. • Host a pancake breakfast before, between or after SCOUT SUNDAY / services. SABBATH / JUMUAH • Collect food for a local food pantry. • Light a series of 12 candles while briefly explaining the points of the Scout Law. • Show a video or photo slideshow of highlights from the pack, troop, crew or ship’s past year. • Bake (or buy) doughnuts to share before services. • Make a soft recruiting play by setting up a table Is your Pack planning a Scout Sunday, Scout Shabbat, near the entrance to answer questions about your or Scout Jumuah this year?? Scout unit. You should consider doing so - For more information, checkout – ✓ Scout Sunday – February 4 ✓ Scout Shabbat -Sundown to Sundown, February 9 to 10 ✓ Scout Jumuah – February 9 https://blog.scoutingmagazine.org BALOO'S BUGLE – (Part I – Monthly Fun Stuff – Jan 2018 RT, Feb 2018 Program) Page 2 PHILMONT CS RT TABLE OF CONTENTS SUPPLEMENT SCOUT SUNDAY / SABBATH / JUMUAH ............ -

Is Over – Now What? Restoring the Four Freedoms As a Foundation for Peace and Security

The “War on Terror” Is Over – Now What? Restoring the Four Freedoms as a Foundation for Peace and Security Mark R. Shulman* As for our common defense, we reject as false the choice between our safety and our ideals. Our founding fathers, faced with perils that we can scarcely imagine, drafted a charter to assure the rule of law and the rights of man, a charter expanded by the blood of generations. Those ideals still light the world, and we will not give them up for expedience’s sake. And so, to all other peoples and governments who are watching today, from the grandest capitals to the small village where my father was born: know that America is a friend of each nation and every man, woman and child who seeks a future of peace and dignity, and we are ready to lead once more. – Barack H. Obama Inaugural Address, Jan. 20, 20091 The so-called “war on terror” has ended.2 By the end of his first week in office, President Barack H. Obama had begun the process of dismantling some of the most notorious “wartime” measures.3 A few weeks before, recently reappointed Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates had clearly forsaken the contentious label in a post-election essay on U.S. strategy in Foreign Affairs.4 Gates noted this historic shift in an almost offhanded * Assistant Dean for Graduate Programs and International Affairs and Adjunct Professor of Law at Pace University School of Law. A previous iteration of this article appeared in the Fordham Law Review. -

Honoring America's Spirit

September 2017 Vol. 5, Number 6 Gazette Dedicated to John Knox Village Inform, Inspire, Involve A Life Plan Continuing Care Retirement Community Published Monthly by John Knox Village, 651 S.W. Sixth Street, Pompano Beach, Florida 33060 IN THIS MONTH’S ISSUE Honoring America’s Spirit Chef Mark’s Recipe That Can’t Be Beet ................ 3 The Artistic Genius Of Norman Perceval Rockwell he ex- Nona Smith Gazette Contributor Ttraordi- nary oeuvre of Norman Rockwell deserves a second look, as his work reflects many of the concerns we have today: The threat of war, tough economic times, cul- tural, social and racial divides, and reveals the true genius of one of the most extraordinary American artists of his time. Looking at Rockwell’s Rockwell Memories ........ 3 extensive collection of drawings, paintings and sketches shows his Visit Us In September .... 5 compositional brilliance, his acuity as a story teller and his celebrated Crossword Puzzle ......... 5 ability to bring people to life through paint, paper and canvas. Autumn Sales Event ....... 6 The Early Years South Florida Events, Born Norman Percevel Rockwell Shows & Arts .................. 8 in New York City in 1894, Rock- well had an innate artistic talent. Golden Anniversary ..... 8 By the age of 14, all he wanted The Psychiatrist Is In ..... 9 was to be an artist. At 16, his focus was so intent on his art, that he dropped out of high school and enrolled at the National Academy of Design. He later transferred to the prestigious Art Students League of New York where he studied with Thomas Fogarty for illustra- “Triple Self-Portrait,” by Norman Rockwell, 1960. -

Copyright by Caroline Booth Pinkston 2019

Copyright by Caroline Booth Pinkston 2019 The Dissertation Committee for Caroline Booth Pinkston Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: Remembering Ruby, Forgetting Frantz: Civil Rights Memory, Education Reform, and the Struggle for Social Justice in New Orleans Public Schools, 1960-2014 Committee: Julia Mickenberg, Supervisor Cary Cordova Janet Davis Shirley Thompson Noah De Lissovoy Remembering Ruby, Forgetting Frantz: Civil Rights Memory, Education Reform, and the Struggle for Social Justice in New Orleans Public Schools, 1960-2014 by Caroline Booth Pinkston Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2019 Dedication For the faculty, staff, and - most of all - the students of Validus Preparatory Academy, my first and best guides into the world of teaching and learning, and the ones who first made me fall in love with what a school can be. Acknowledgements This project owes a great deal to the faculty and staff at the University of Texas who helped to usher it into existence. I am grateful to my committee - Julia Mickenberg, Cary Cordova, Shirley Thompson, Janet Davis, and Noah De Lissovoy - for their care and attention to this project. But even more so, I am grateful for their generosity, guidance, and mentorship throughout the past seven years - for their teaching, their conversation, and their encouragement. In particular, I wish to thank Julia, my advisor and the chair of my committee, for her many close and careful readings of this project, and for her consistent support of my goals.