A History of Global Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emperor Hirohito (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 27, folder “State Visits - Emperor Hirohito (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 27 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE EMPEROR OF JAPAN ~ . .,1. THE EMPEROR OF JAPAN A Profile On the Occasion of The Visit by The Emperor and Empress to the United States September 30th to October 13th, 1975 by Edwin 0. Reischauer The Emperor and Empress of japan on a quiet stroll in the gardens of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. Few events in the long history of international relations carry the significance of the first visit to the United States of the Em peror and Empress of Japan. Only once before has the reigning Emperor of Japan ventured forth from his beautiful island realm to travel abroad. On that occasion, his visit to a number of Euro pean countries resulted in an immediate strengthening of the bonds linking Japan and Europe. -

Neville Chamberlain's Announcement of the Introduction of Conscription To

FRANCO-BRITISH RELATIONS AND THE QUESTION OF CONSCRIPTION IN BRITAIN, 1938-1939 ABSTRACT - This article examines the relationship interaction between the French campaign for the introduction of British conscription during 1938-39 and the ebbs and flows of British public opinion on the same issue. In particular, it will demonstrate how French pressure for conscription varied in intensity depending on their perceptions of British opinion on the subject. It was this interaction between diplomatic and domestic pressures that ultimately compelled the British government to introduce conscription in April 1939. Furthermore, the issue of conscription also sheds light on the wider issue of Franco-British relations, revealing how French foreign policy was neither dictated by an ‘English Governess’ nor pursued independently of Great Britain. When Neville Chamberlain announced the introduction of conscription to the House of Commons on 26 April 1939 he not only reneged on previous promises but deviated from the traditional British aversion to peacetime compulsory service. Chamberlain defended himself by arguing that current international tensions could not be described as ‘peace-time in any sense in which the term could fairly be used’.1 Nonetheless, introducing conscription – albeit in a limited form2 – was alien to British tradition. How, therefore, can the decision be explained? What motivated the government to take such a step? This article sheds new light on the British decision to implement conscription in April 1939, moving beyond existing analyses by showing that the decision was motivated not only by a fusion of domestic and international pressures but by the interaction of the two. More specifically, contends that French pressure for British conscription ebbed and flowed in direct correlation to the French government’s perceptions of the British public’s attitude towards compulsory military service. -

“American Chronicles: the Art of Norman Rockwell at TAM” Published in Artdish, March 2011 2011 Jane Richlovsky

“American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell at TAM” published in Artdish, March 2011 2011 Jane Richlovsky Norman Rockwell's painting "Discovery", currently on display at the Tacoma Art Museum, depicts a pajama-clad young boy finding a Santa Claus suit and false beard in Dad's bureau drawer, incriminating evidence of the old man's fakery. The picture appeared on the cover of the December 29, 1956 Saturday Evening Post. It's hard at first to get past the boy's facial expression. His eyes are popping out of his head, in a way that irritatingly foreshadows the ubiquitous Macauley Caulkin "Home Alone" publicity shot. However unfortunate this association, the expression is so utterly unconvincing as a portrayal of having one's cherished mythology punctured, that one can't help but think the kid never believed in Santa in the first place. Considering that this is one of many Rockwell paintings that repeatedly revisit the Santa-unmasking narrative over decades, you have to wonder: Is the guy responsible for our vision of the American Myth perhaps telling us we shouldn't be so surprised or upset that it's all made up? I've always found sunny, idealized, 1950's-style Leave-it-to-Beaver archetypal America intriguing, compelling, and horrifying. I'm far from alone in this, but I have spent more time than most people immersed in its ephemera, interrogating, digesting, cutting up, reconfiguring, and spitting back out endless images from midcentury domestic magazines. Imagine my shock when, after all that, putting together a show of the resulting paintings, I encounter a dealer's misbegotten press release, or an enthusiastic patron, praising what I thought was my scathing critique as a fond, nostalgic look back at a "simpler time". -

Rule of Law Guide for Politicians

Rule of Law A guide for politicians 2 Copyright © The Raoul Wallenberg Institute of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law and the Hague Institute for the Internationalisation of Law 2012 ISBN: 91-86910-99-X This publication is circulated subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be lent, sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers’ prior consent in any form of binding, or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. The Guide may be translated into other languages subject to the approval of the publishers and provided that the Foreword is included and that the translation is a true representation of the text. Translators at the national level are encouraged to perform this work pro bono. The publishers would be grateful for a copy of translations made so that they can be posted on their websites. Published by The Raoul Wallenberg Institute of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law Stora Gråbrödersgatan 17 B P.O. Box 1155 SE-221 05 Lund Sweden Phone: +46 46 222 12 00 Fax: +46 46 222 12 22 E-mail: [email protected] www.rwi.lu.se The Hague Institute for the Internationalisation of Law (HiiL) Anna van Saksenlaan 51 P.O. Box 93033 2509 AA The Hague The Netherlands Phone: +31 70 349 4405 Fax: +31 70 349 4400 E-mail: [email protected] www.hiil.org Cover: Publimarket B.V., The Netherlands 3 Rule of Law A Guide for Politicians TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ...................................................................................... -

The Problem of War Aims and the Treaty of Versailles Callaghan, JT

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Salford Institutional Repository The problem of war aims and the Treaty of Versailles Callaghan, JT Titl e The problem of war aims and the Treaty of Versailles Aut h or s Callaghan, JT Typ e Book Section URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/46240/ Published Date 2 0 1 8 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non- commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected] . 13 The problem of war aims and the Treaty of Versailles John Callaghan Why did Britain go to war in 1914? The answer that generated popular approval concerned the defence of Belgian neutrality, defiled by German invasion in the execution of the Schlieffen Plan. Less appealing, and therefore less invoked for public consumption, but broadly consistent with this promoted justification, was Britain’s long-standing interest in maintaining a balance of power on the continent, which a German victory would not only disrupt, according to Foreign Office officials, but replace with a ‘political dictatorship’ inimical to political freedom.1 Yet only 6 days before the British declaration of war, on 30 July, the chairman of the Liberal Foreign Affairs Group, Arthur Ponsonby, informed Prime Minister Asquith that ‘nine tenths of the [Liberal] party’ supported neutrality. -

Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg

Smithsonian American Art Museum TEACHER’S GUIDE from the collections of GEORGE LUCAS and STEVEN SPIELBERG 1 ABOUT THIS RESOURCE PLANNING YOUR TRIP TO THE MUSEUM This teacher’s guide was developed to accompany the exhibition Telling The Smithsonian American Art Museum is located at 8th and G Streets, NW, Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and above the Gallery Place Metro stop and near the Verizon Center. The museum Steven Spielberg, on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in is open from 11:30 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. Admission is free. Washington, D.C., from July 2, 2010 through January 2, 2011. The show Visit the exhibition online at http://AmericanArt.si.edu/rockwell explores the connections between Norman Rockwell’s iconic images of American life and the movies. Two of America’s best-known modern GUIDED SCHOOL TOURS filmmakers—George Lucas and Steven Spielberg—recognized a kindred Tours of the exhibition with American Art Museum docents are available spirit in Rockwell and formed in-depth collections of his work. Tuesday through Friday from 10:00 a.m. to 11:30 a.m., September through Rockwell was a masterful storyteller who could distill a narrative into December. To schedule a tour contact the tour scheduler at (202) 633-8550 a single moment. His images contain characters, settings, and situations that or [email protected]. viewers recognize immediately. However, he devised his compositional The docent will contact you in advance of your visit. Please let the details in a painstaking process. Rockwell selected locations, lit sets, chose docent know if you would like to use materials from this guide or any you props and costumes, and directed his models in much the same way that design yourself during the visit. -

The Origins of the Imperial Presidency and the Framework for Executive Power, 1933-1960

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 4-2013 Building A House of Peace: The Origins of the Imperial Presidency and the Framework for Executive Power, 1933-1960 Katherine Elizabeth Ellison Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ellison, Katherine Elizabeth, "Building A House of Peace: The Origins of the Imperial Presidency and the Framework for Executive Power, 1933-1960" (2013). Dissertations. 138. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/138 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUILDING A HOUSE OF PEACE: THE ORIGINS OF THE IMPERIAL PRESIDENCY AND THE FRAMEWORK FOR EXECUTIVE POWER, 1933-1960 by Katherine Elizabeth Ellison A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Western Michigan University April 2013 Doctoral Committee: Edwin A. Martini, Ph.D., Chair Sally E. Hadden, Ph.D. Mark S. Hurwitz, Ph.D. Kathleen G. Donohue, Ph.D. BUILDING A HOUSE OF PEACE: THE ORIGINS OF THE IMPERIAL PRESIDENCY AND THE FRAMEWORK FOR EXECUTIVE POWER, 1933-1960 Katherine Elizabeth Ellison, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2013 This project offers a fundamental rethinking of the origins of the imperial presidency, taking an interdisciplinary approach as perceived through the interactions of the executive, legislative, and judiciary branches of government during the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. -

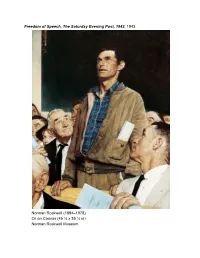

2-A Rockwell Freedom of Speech

Freedom of Speech, The Saturday Evening Post, 1943, 1943 Norman Rockwell (1894–1978) Oil on Canvas (45 ¾ x 35 ½ in) Norman Rockwell Museum NORMAN ROCKWELL [1894–1978] 19 a Freedom of Speech, The Saturday Evening Post, 1943 After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, What is uncontested is that his renditions were not only vital to America was soon bustling to marshal its forces on the home the war effort, but have become enshrined in American culture. front as well as abroad. Norman Rockwell, already well known Painting the Four Freedoms was important to Rockwell for as an illustrator for one of the country’s most popular maga- more than patriotic reasons. He hoped one of them would zines, The Saturday Evening Post, had created the affable, gangly become his statement as an artist. Rockwell had been born into character of Willie Gillis for the magazine’s cover, and Post read- a world in which painters crossed easily from the commercial ers eagerly followed Willie as he developed from boy to man world to that of the gallery, as Winslow Homer had done during the tenure of his imaginary military service. Rockwell (see 9-A). By the 1940s, however, a division had emerged considered himself the heir of the great illustrators who left their between the fine arts and the work for hire that Rockwell pro- mark during World War I, and, like them, he wanted to con- duced. The detailed, homespun images he employed to reach tribute something substantial to his country. a mass audience were not appealing to an art community that A critical component of the World War II war effort was the now lionized intellectual and abstract works. -

Fortress of Liberty: the Rise and Fall of the Draft and the Remaking of American Law

Fortress of Liberty: The Rise and Fall of the Draft and the Remaking of American Law Jeremy K. Kessler∗ Introduction: Civil Liberty in a Conscripted Age Between 1917 and 1973, the United States fought its wars with drafted soldiers. These conscript wars were also, however, civil libertarian wars. Waged against the “militaristic” or “totalitarian” enemies of civil liberty, each war embodied expanding notions of individual freedom in its execution. At the moment of their country’s rise to global dominance, American citizens accepted conscription as a fact of life. But they also embraced civil liberties law – the protections of freedom of speech, religion, press, assembly, and procedural due process – as the distinguishing feature of American society, and the ultimate justification for American military power. Fortress of Liberty tries to make sense of this puzzling synthesis of mass coercion and individual freedom that once defined American law and politics. It also argues that the collapse of that synthesis during the Cold War continues to haunt our contemporary legal order. Chapter 1: The World War I Draft Chapter One identifies the WWI draft as a civil libertarian institution – a legal and political apparatus that not only constrained but created new forms of expressive freedom. Several progressive War Department officials were also early civil libertarian innovators, and they built a system of conscientious objection that allowed for the expression of individual difference and dissent within the draft. These officials, including future Supreme Court Justices Felix Frankfurter and Harlan Fiske Stone, believed that a powerful, centralized government was essential to the creation of a civil libertarian nation – a nation shaped and strengthened by its diverse, engaged citizenry. -

BAM 50 State Initiative Art Project—A Partnership with for Freedoms—Activates Civic Engagement Through Art Work Creation, Saturday, Oct 20

BAM 50 State Initiative Art Project—a partnership with For Freedoms—activates civic engagement through art work creation, Saturday, Oct 20 Free public event will be led by Brooklyn visual artist Katherine Toukhy Oct 5, 2018/Brooklyn, NY—The Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) has partnered with For Freedoms in an afternoon of civic engagement on Saturday, Oct 20 from 1–3pm at the South Site Plaza (Lafayette Ave, corner of Flatbush Ave). Attendees will participate in an art-making project, led by Brooklyn visual artist Katherine Toukhy, to create and share social and political statements with the community. Images of finished artworks will be photographed and displayed on BAM’s outdoor digital signpost on the corner of Flatbush Ave and Lafayette Ave—running on a loop until the mid-term elections in November. BAM’s VP of Education and Community Engagement Coco Killingsworth said, “We’re excited to join with For Freedoms and Katherine Toukhy in gathering community members for this creative civic activation. We hope this event inspires all of us to use our voices to engage in the democratic process.” For Freedoms started in 2016 as a platform for civic engagement, discourse, and direct action for artists in the United States. Inspired by Norman Rockwell’s 1943 painting of the four universal freedoms articulated by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1941—freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear—For Freedoms seeks to use art to deepen public discussions of civic issues and core values, and to clarify that citizenship in American society is deepened by participation, not by ideology. -

![Arthur Sweetser Papers [Finding Aid]. Library Of](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5305/arthur-sweetser-papers-finding-aid-library-of-635305.webp)

Arthur Sweetser Papers [Finding Aid]. Library Of

Arthur Sweetser Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2013 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms013059 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm78042085 Prepared by Manuscript Division Staff Collection Summary Title: Arthur Sweetser Papers Span Dates: 1913-1961 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1919-1947) ID No.: MSS42085 Creator: Sweetser, Arthur, 1888-1968 Extent: 22,350 items ; 95 containers plus 4 oversize ; 36.6 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Public official and journalist. Correspondence, diaries, memoranda, press releases, newspaper clippings, speeches, articles, scrapbooks, and other papers relating to Sweetser's career in journalism and diplomacy. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Acheson, Dean, 1893-1971--Correspondence. Baruch, Bernard M. (Bernard Mannes), 1870-1965--Correspondence. Comert, Pierre--Correspondence. Croly, Herbert David, 1869-1930--Correspondence. Davis, Elmer Holmes, 1890-1958--Correspondence. Davis, Malcolm W. (Malcolm Waters), 1899- --Correspondence. Drummond, Eric, Sir, 1876- --Correspondence. Fosdick, Raymond B. (Raymond Blaine), 1883-1972--Correspondence. Gerig, Benjamin, 1894-1976--Correspondence. Gilchrist, Huntington, 1891-1975--Correspondence. Grew, Joseph C. (Joseph Clark), 1880-1965--Correspondence. Hambro, Carl Joachim, 1885-1964--Correspondence. House, Edward Mandell, 1858-1938--Correspondence. Hudson, Manley O. -

Yearbook 1988 Supreme Court Historical Society

YEARBOOK 1988 SUPREME COURT HISTORICAL SOCIETY OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES, JR. Associate Justice, 1902-1933 YEARBOOK 1988 SUPREME COURT HISTORICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS Warren E. Burger Chief Justice of the United States (1969-1986) Honorary Chainnan Kenneth Rush, Chainnan Justin A. Stanley, President PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Kenneth S. Geller, Chainnan Alice L. O'Donnell E. Barrett Prettyman, Jr. Michael Cardozo BOARD OF EDITORS Gerald Gunther Craig Joyce Michael W. McConnell David O'Brien Charles Alan Wright STAFF EDITORS Clare H. Cushman David T. Pride Barbara R. Lentz Kathleen Shurtleff CONSULTING EDITORS James J. Kilpatrick Patricia R. Evans ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Officers and Trustees of the Supreme Court Historical Society would like to thank the Charles Evans Hughes Foundation for its generous support of the publication of this Yearbook. YEARBOOK 1988 Supreme Court Historical Society Establishing Justice 5 Sandra Day O'Connor Perspectives on Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. Self-Preference, Competition and the Rule of Force: The Holmesian Legacy 11 Gary Jan Aichele Sutherland Remembers Holmes 18 David M. O'Brien Justice Holmes and Lady C 26 John S. Monagan Justice Holmes and the Yearbooks 37 Milton C Handler and Michael Ruby William Pinkney: The Supreme Court's Greatest Advocate 40 Stephen M. Shapiro Harper's Weekly Celebrates the Centennial of the Supreme Court 46 Peter G. Fish Looking Back on Cardozo Justice Cardozo, One-Ninth of the Supreme Court 50 Milton C Handler and Michael Ruby Judging New York Style: A Brief Retrospective of Two New York Judges 60 Andrew L. Kaufman Columbians as Chief Justices: John Jay, Charles Evans Hughes, Harlan Fiske Stone 66 Richard B.