Norman Rockwell: Artist Or Illustrator? | Abigail Rockwell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Federal Reserve's Catch-22: 1 a Legal Analysis of the Federal Reserve's Emergency Powers

~ UNC Jill SCHOOL OF LAW *'/(! 4 --/! ,.%'! " ! ! " *''*1.$%-) %.%*)'1*,&-. $6+-$*',-$%+'1/)! /)% ,.*".$! )&%)#) %))!1*((*)- !*((!) ! %..%*) 5*(-*,.!, 7;:9;8;<= 0%''!. $6+-$*',-$%+'1/)! /)%0*' %-- 5%-*.!%-,*/#$..*2*/"*,",!!) *+!)!--2,*'%)1$*',-$%+!+*-%.*,2.$-!!)!+.! "*,%)'/-%*)%)*,.$,*'%) )&%)#)-.%./.!2)/.$*,%3! ! %.*,*",*'%)1$*',-$%+!+*-%.*,2*,(*,!%)"*,(.%*)+'!-!*).. '1,!+*-%.*,2/)! / The Federal Reserve's Catch-22: 1 A Legal Analysis of the Federal Reserve's Emergency Powers I. INTRODUCTION The federal government's role in the buyout of The Bear Stearns Companies (Bear) by JPMorgan Chase (JPMorgan) will be of lasting significance because it shaped a pivotal moment in the most threatening financial crisis since The Great Depression.2 On March 13, 2008, Bear informed "the Federal Reserve and other government agencies that its liquidity position had significantly deteriorated, and it would have to file for bankruptcy the next day unless alternative sources of funds became available."3 The potential impact of Bear's insolvency to the global financial system4 persuaded officials at the Federal Reserve (the Fed) and the United States Department of the Treasury (Treasury) to take unprecedented regulatory action.5 The response immediately 1. JOSEPH HELLER, CATCH-22 (Laurel 1989). 2. See Turmoil in the Financial Markets: Testimony Before the H. Oversight and Government Reform Comm., llO'h Cong. -- (2008) [hereinafter Greenspan Testimony] (statement of Dr. Alan Greenspan, former Chairman, Federal Reserve Board of Governors) ("We are in the midst of a once-in-a century credit tsunami."); Niall Ferguson, Wall Street Lays Another Egg, VANITY FAIR, Dec. 2008, at 190, available at http://www.vanityfair.com/politics/features/2008/12/banks200812 ("[B]eginning in the summer of 2007, [the global economy] began to self-destruct in what the International Monetary Fund soon acknowledged to be 'the largest financial shock since the Great Depression."'); Jeff Zeleny and Edmund L. -

Crystal Anniversary: Nmai Celebrates 15 Years with Gala and Catalog Of

PREVIEWING UPCOMING EXHIBITIONS, EVENTS, SALES AND AUCTIONS OF HISTORIC FINE ART AMrICAN ISSUE 22 July/August 2015 FMAGAZINEI AFA22.indd 2 6/2/15 10:30 AM EVENT PREVIEW: NEWPORT, RI Crystal Anniversary National Museum of American Illustration celebrates 15 years with gala and catalog of Norman Rockwell and His Contemporaries exhibition July 30, 6 p.m. National Museum of American Illustration Vernon Court 492 Bellevue Avenue Newport, RI 02840 t: (401) 851-8949 www.americanillustration.org o commemorate the 15th anniversary of the National TMuseum of American Illustration (NMAI), the museum will host a gala and live auction July 30 in connection with its current exhibition Norman Rockwell and His Contemporaries, running through October 12. The gala features cocktails, dining, dancing and celebrity appearances, while the auction includes work by Rockwell, Maxfield Parrish, and Howard Chandler Christy, among others. An auction highlight is a portrait of former President John F. Kennedy by Rockwell. The illustration was completed for the cover of The Saturday Evening Post and was done during the Cuban missile crisis. By using a three-quarter portrait pose with Kennedy’s chin resting on his hand and a dark background, the artist was able to express the heaviness Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), Portrait of John F. Kennedy, The Saturday Evening Post cover, April 6, of the president’s decisions to the 1963. Oil on canvas, 22 x 18 in., signed lower right. Estimate: $4/6 million viewer. “We lived through it. It was a big The portrait was the second and last Phoebus on Halzaphron, a short story by deal for us. -

Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg

Smithsonian American Art Museum TEACHER’S GUIDE from the collections of GEORGE LUCAS and STEVEN SPIELBERG 1 ABOUT THIS RESOURCE PLANNING YOUR TRIP TO THE MUSEUM This teacher’s guide was developed to accompany the exhibition Telling The Smithsonian American Art Museum is located at 8th and G Streets, NW, Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and above the Gallery Place Metro stop and near the Verizon Center. The museum Steven Spielberg, on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in is open from 11:30 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. Admission is free. Washington, D.C., from July 2, 2010 through January 2, 2011. The show Visit the exhibition online at http://AmericanArt.si.edu/rockwell explores the connections between Norman Rockwell’s iconic images of American life and the movies. Two of America’s best-known modern GUIDED SCHOOL TOURS filmmakers—George Lucas and Steven Spielberg—recognized a kindred Tours of the exhibition with American Art Museum docents are available spirit in Rockwell and formed in-depth collections of his work. Tuesday through Friday from 10:00 a.m. to 11:30 a.m., September through Rockwell was a masterful storyteller who could distill a narrative into December. To schedule a tour contact the tour scheduler at (202) 633-8550 a single moment. His images contain characters, settings, and situations that or [email protected]. viewers recognize immediately. However, he devised his compositional The docent will contact you in advance of your visit. Please let the details in a painstaking process. Rockwell selected locations, lit sets, chose docent know if you would like to use materials from this guide or any you props and costumes, and directed his models in much the same way that design yourself during the visit. -

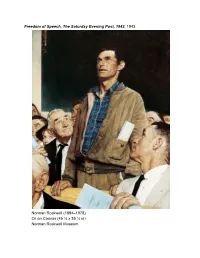

2-A Rockwell Freedom of Speech

Freedom of Speech, The Saturday Evening Post, 1943, 1943 Norman Rockwell (1894–1978) Oil on Canvas (45 ¾ x 35 ½ in) Norman Rockwell Museum NORMAN ROCKWELL [1894–1978] 19 a Freedom of Speech, The Saturday Evening Post, 1943 After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, What is uncontested is that his renditions were not only vital to America was soon bustling to marshal its forces on the home the war effort, but have become enshrined in American culture. front as well as abroad. Norman Rockwell, already well known Painting the Four Freedoms was important to Rockwell for as an illustrator for one of the country’s most popular maga- more than patriotic reasons. He hoped one of them would zines, The Saturday Evening Post, had created the affable, gangly become his statement as an artist. Rockwell had been born into character of Willie Gillis for the magazine’s cover, and Post read- a world in which painters crossed easily from the commercial ers eagerly followed Willie as he developed from boy to man world to that of the gallery, as Winslow Homer had done during the tenure of his imaginary military service. Rockwell (see 9-A). By the 1940s, however, a division had emerged considered himself the heir of the great illustrators who left their between the fine arts and the work for hire that Rockwell pro- mark during World War I, and, like them, he wanted to con- duced. The detailed, homespun images he employed to reach tribute something substantial to his country. a mass audience were not appealing to an art community that A critical component of the World War II war effort was the now lionized intellectual and abstract works. -

Baloo's Bugle

BALOO'S BUGLE Volume 24, Number 6 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- “If you want children to keep their feet on the ground, put some responsibility on their shoulders.” Abigail Van Buren --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- January 2018 Cub Scout Roundtable February 2018 Program Ideas CHEERFUL / ABRACADABRA 2017-2018 CS Roundtable Planning Guide –No themes or month specified material PART I – MONTHLY FUN STUFF 12 ways to celebrate Scout Sunday, Scout Sabbath and/or Scout Jumuah: • Wear your Scout uniform to worship services. • Present religious emblems to Scouts, & leaders who have earned them in the past year. • Recruit several Scouts or Scouters to read passages from religious text. • Involve uniformed Scouts as greeters, ushers, gift bearers or the color guard. • Invite a Scout or Scouter to serve as a guest speaker or deliver the sermon. • Hold an Eagle Scout court of honor during the worship service. • Host a pancake breakfast before, between or after SCOUT SUNDAY / services. SABBATH / JUMUAH • Collect food for a local food pantry. • Light a series of 12 candles while briefly explaining the points of the Scout Law. • Show a video or photo slideshow of highlights from the pack, troop, crew or ship’s past year. • Bake (or buy) doughnuts to share before services. • Make a soft recruiting play by setting up a table Is your Pack planning a Scout Sunday, Scout Shabbat, near the entrance to answer questions about your or Scout Jumuah this year?? Scout unit. You should consider doing so - For more information, checkout – ✓ Scout Sunday – February 4 ✓ Scout Shabbat -Sundown to Sundown, February 9 to 10 ✓ Scout Jumuah – February 9 https://blog.scoutingmagazine.org BALOO'S BUGLE – (Part I – Monthly Fun Stuff – Jan 2018 RT, Feb 2018 Program) Page 2 PHILMONT CS RT TABLE OF CONTENTS SUPPLEMENT SCOUT SUNDAY / SABBATH / JUMUAH ............ -

The Book House

PETER BLUM GALLERY Where is Our Reckoning? September 29, 2020 Text by Catherine Wagley Mock Bon Appétit cover by Joe Rosenthal (@joe_rosenthal). For weeks, I have been preoccupied with the brilliantly crafted tweets of freelance food and wine writer Tammie Teclemariam, who has been fueling, supporting, and live-tweeting reckonings in food media since early June. Her early grand slam, tweeted alongside a 2004 photo of now-former Bon Appétit editor-in-chief Adam Rapoport in brown face (two anonymous sources sent her the photo, which the editor allegedly kept on his desk),1 read: “I don’t know why Adam Rapoport doesn’t just write about Puerto Rican food for @bonappetit himself!!!”2 Hours later, Rapaport—who, according multiple accounts, nurtured a toxic, discriminatory culture at the publication—had resigned. But perhaps my favorite tweet came after Teclemariam’s tweets contributed to the resignation of Los Angeles Times food section editor Peter Meehan: “I’m so glad the real journalism can start now that everyone is running their mouth.”3 In its glib concision, her tweet underscored the ideal aim of many recent so-called media call-outs: to expose, and hopefully excise, a toxicity that narrows, stifles, and handicaps writing about culture—the importance of which has been underscored by the ongoing uprisings against violent systemic racism. Blumarts Inc. 176 Grand Street Tel + 1 212 244 6055 www.peterblumgallery.com New York, NY 10013 Fax + 1 212 244 6054 [email protected] PETER BLUM GALLERY Not everyone appreciates that tweets like -

Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial

Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law Volume 11 Issue 4 Article 3 2006 Does the Law Encourage Unethical Conduct in the Securities Industry? Di Lorenzo Vincent Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/jcfl Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, and the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Di Lorenzo Vincent, Does the Law Encourage Unethical Conduct in the Securities Industry?, 11 Fordham J. Corp. & Fin. L. 765 (2006). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/jcfl/vol11/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOES THE LAW ENCOURAGE UNETHICAL CONDUCT IN THE SECURITIES INDUSTRY? Vincent Di Lorenzo* A 2002 Citigroup Inc. memo, released as part of a Florida lawsuit, shows that the bank's own analysts were reluctant to publish less- biased research over concerns of a backlash from its investment bankers. John Hoffmann, the former head of equity research at Citigroup's Salomon Smith Barney unit, wrote in March 2002 that the firm's analysts were considering an increase in the number of "negative" ratings on stocks. In the same memo to Michael Carpenter, then head of Citigroup's corporate and investment bank, Hoffmann said doing so would threaten more than $16 billion in fees and risk putting the firm at a disadvantage. -

Honoring America's Spirit

September 2017 Vol. 5, Number 6 Gazette Dedicated to John Knox Village Inform, Inspire, Involve A Life Plan Continuing Care Retirement Community Published Monthly by John Knox Village, 651 S.W. Sixth Street, Pompano Beach, Florida 33060 IN THIS MONTH’S ISSUE Honoring America’s Spirit Chef Mark’s Recipe That Can’t Be Beet ................ 3 The Artistic Genius Of Norman Perceval Rockwell he ex- Nona Smith Gazette Contributor Ttraordi- nary oeuvre of Norman Rockwell deserves a second look, as his work reflects many of the concerns we have today: The threat of war, tough economic times, cul- tural, social and racial divides, and reveals the true genius of one of the most extraordinary American artists of his time. Looking at Rockwell’s Rockwell Memories ........ 3 extensive collection of drawings, paintings and sketches shows his Visit Us In September .... 5 compositional brilliance, his acuity as a story teller and his celebrated Crossword Puzzle ......... 5 ability to bring people to life through paint, paper and canvas. Autumn Sales Event ....... 6 The Early Years South Florida Events, Born Norman Percevel Rockwell Shows & Arts .................. 8 in New York City in 1894, Rock- well had an innate artistic talent. Golden Anniversary ..... 8 By the age of 14, all he wanted The Psychiatrist Is In ..... 9 was to be an artist. At 16, his focus was so intent on his art, that he dropped out of high school and enrolled at the National Academy of Design. He later transferred to the prestigious Art Students League of New York where he studied with Thomas Fogarty for illustra- “Triple Self-Portrait,” by Norman Rockwell, 1960. -

Olio Volume 19 Issue 2 2002

~olio Volume 19 The ·po Issue 2 2002 The From the Director Norman Rockwell I am pleased to announce the formation the museum will offer of the Norman Rockwell Museum National a sampler of foods to Museum Council, upon the conclusion of our museum visitors at at Stockbridge national tour, Pictures for the American our new Terrace Cafe People. The Council will provide a forum during the summer and fall. Sip a refreshing BOARD OF TRUSTEES for the Museum's national patrons and iced tea and enjoy the view after your visit to Bobbie Crosby· President Perri Petricca • First Vice President collectors, who will serve as ambassadors our wonderful summer exhibitions. We thank Lee Williams' Second Vice President for the Museum across the nation. the Town of Stockbridge Board of Selectmen Steven Spielberg· Third Vice President James W. Ireland' Treasurer and the Red Lion Inn for being our partner in Roselle Kline Chartock • Clerk The Board of Trustees has nominated a offering hospitality to our visitors. Robert Berle Ann Fitzpatrick Brown select group of friends and supporters to Daniel M. Cain join us in the stewardship of our mission. Jan Cohn As part of the Berkshire County-wide arts Catharine B. Deely The Council is advisory to and complements festival, the Vienna Project, the museum Michelle Gillett Elaine S. Gunn the work of Norman Rockwell Museum opened Viennese illustrator Lisbeth Zwerger's Ellen Kahn Trustees and staff. Council members will Land of Oz with a Viennese coffee house, Jeffrey Kleiser Luisa Kreisberg provide national outreach and offer advice remarks by Dr. -

Letter Received in Response to Appeals Court Decision

[email protected] June 28, 2005 (202) 887-3746 (202) 530-9653 VIA E-MAIL Mr. Jonathan G. Katz Secretary Securities and Exchange Commission 100 Fifth Street, N.E. Washington, DC 20549 Re: Investment Company Governance Rule; File No. S7-03-04 Dear Mr. Katz: I am enclosing the following materials for inclusion in the rulemaking record in advance of the June 29 Open Meeting concerning the above-titled proceeding: • A June 21, 2005 article from Bloomberg.com, titled “SEC Must Reconsider Fund Governance Rule, Court Says”; • An email from C. Meyrick Payne of Management Practice Inc.; • A June 23, 2005 article from the Wall Street Journal, titled “Donaldson's Last Stand”; • A June 23, 2005 article from CBS MarketWatch, titled “Business group urges SEC to hold off fund vote”; • A letter from the Honorable Harvey L. Pitt to the Commission; • A June 24, 2005 article from Dow Jones Newswire, titled “Republican Senators Urge SEC to Defer Action on Fund Rule”; • A June 24, 2005 article from the Washington Post, titled “National Briefing: Regulation”; • A June 24, 2005 article from Bloomberg.com; • A June 25 New York Times article, titled “Ex-Officials Urge S.E.C. to Postpone a Vote”; • A June 28, 2005 New York Times article, titled “S.E.C. Chief Defends Timing of Fund Vote”; • A June 28, 2005 Wall Street Journal article, titled “Donaldson's Finale Draws Uproar”; and • A PDF of a letter from eight United States Senators to the Commission. Very truly yours, Cory J. Skolnick Enclosures cc: Hon. William H. Donaldson, Chairman, SEC (via hand delivery w/ enclosures) Hon. -

Enterprise and Individual Risk Management

Enterprise and Individual Risk Management v. 1.0 This is the book Enterprise and Individual Risk Management (v. 1.0). This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms. This book was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz (http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book. Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/attribution.html?utm_source=header). For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there. ii Table of Contents About the Authors................................................................................................................. 1 Acknowledgments................................................................................................................. 6 Dedications............................................................................................................................ -

Copyright by Caroline Booth Pinkston 2019

Copyright by Caroline Booth Pinkston 2019 The Dissertation Committee for Caroline Booth Pinkston Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: Remembering Ruby, Forgetting Frantz: Civil Rights Memory, Education Reform, and the Struggle for Social Justice in New Orleans Public Schools, 1960-2014 Committee: Julia Mickenberg, Supervisor Cary Cordova Janet Davis Shirley Thompson Noah De Lissovoy Remembering Ruby, Forgetting Frantz: Civil Rights Memory, Education Reform, and the Struggle for Social Justice in New Orleans Public Schools, 1960-2014 by Caroline Booth Pinkston Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2019 Dedication For the faculty, staff, and - most of all - the students of Validus Preparatory Academy, my first and best guides into the world of teaching and learning, and the ones who first made me fall in love with what a school can be. Acknowledgements This project owes a great deal to the faculty and staff at the University of Texas who helped to usher it into existence. I am grateful to my committee - Julia Mickenberg, Cary Cordova, Shirley Thompson, Janet Davis, and Noah De Lissovoy - for their care and attention to this project. But even more so, I am grateful for their generosity, guidance, and mentorship throughout the past seven years - for their teaching, their conversation, and their encouragement. In particular, I wish to thank Julia, my advisor and the chair of my committee, for her many close and careful readings of this project, and for her consistent support of my goals.