Temples with Transverse Cellae in Republican and Early Imperial Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

00010853-Preview.Pdf

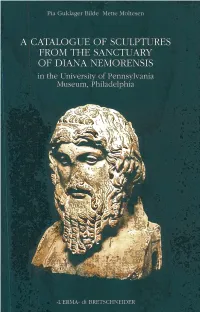

ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI Supplemen turn XXIX A CATALOGUE OF SCULPTURES FROM THE SANCTUARY OF DIANA NEMORENSIS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM, PHILADELPHIA A Catalogue of Sculptures from the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in The University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER ROMAE MMII ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI, SUPPL. XXIX Accademia di Danimarca - Via Omero, 18 - 00197 Rome - Italy Lay-out by the editors © 2002 <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER, Rome PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF GRANTS FROM Knud Højgaards Fond Novo Nordisk Fonden University of Pennsylvania. Museum of archaeology and anthropology A catalogue of sculptures from the sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia / by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen. - Roma: <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER , 2002. - 95 p. : ill. ; 30 cm. (Analecta Romana Instituti Danici. Supplementum ; 29) ISBN 88-8265-211-4 CDD 21. 731.4 1. Sculture in marmo - Collezioni 2. Filadelfia - University of Pennsylvania - Museum of archaeology and anthropology - Cataloghi I. Guldager Bilde, Pia II. Moltesen, Mette The journal ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANICI (ARID) publishes studies within the main range of the Academy's research activities: the arts and humanities, history and archaeology. Intending contributors should get in touch with the editors, who will supply a set of guide- lines and establish a deadline. A print of the article, accompanied y a disk containing the text should be sent to the editors, Accademia di Danimarca, 18 Via Omero, I - 00197 Roma, tel. +39 06 32 65 931, fax +39 06 32 22 717. -

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury. -

Ancient Rome’S Most Exclu- Fare of the Roman Forum Gladiatorial Amphitheatre Sive Neighbourhood

56 ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd A n c i e n t R o m e COLOSSEUM | FORUMS | CAMPIDOGLIO | PIAZZA VENEZIA | BOCCA DELLA VERITÀ & FORUM BOARIUM Five Top Experiences 1 Getting your first 2 Exploring the haunting 4 Walking up Via Sacra, glimpse of the Colosseum ruins of the Palatino (p 60 ), the once grand thorough- (p 58 ). Rome’s towering ancient Rome’s most exclu- fare of the Roman Forum gladiatorial amphitheatre sive neighbourhood. (p 63 ). is both an architectural 3 Coming face to face 5 Surveying the city masterpiece, the blueprint with centuries of awe- spread out beneath you for much modern stadium inspiring art at the historic from atop Il Vittoriano design, and a stark, spine- Capitoline Museums (p67 ). (p 69 ) tingling reminder of the brutality of ancient times. 000000000000000000 000000000000000000 000000000000000000o 000000000000000000Piazza Traian e 0200m 000000000000000000Venezia oro # 00.1miles 000000000000000000ia F 000000000000000000V 000000000000000000arco 000000000000000000M V ri 000000000000000000i San nga d Imperial i V Zi V000000000000000000ia #æ a egli # ia 0000000000000000005 Forums T Via d V00000000000000000000000000 V or 000000000 000000000000000000ia 00000000 ä# d 000000000000a i e n 000000000000000000d 00000000 Via a d 000000000oni 000 i e 000000000000000000'A 00000000 A e 000000Via L 000000 00000000000000000000000000 dei F ' S 000000000000 r le C ccina 000000000000000000a 00000000 a Ba e 000000000000 000000000000000000c 00000000 s o Vi i P s nt r 000000000000000000o 00000000 ori n o p e iet a e'M 00000000000000000000000000 -

Under the Influence of Art: the Effect of the Statues of Horatius Cocles and Cloelia on Valerius

Under the Influence of Art: The Effect of the Statues of Horatius Cocles and Cloelia on Valerius Maximus’ Facta et Dicta Memorabilia In his work, Facta et Dicta Memorabilia, Valerius Maximus stated in the praefatio of his chapter “De Fortitudine” that he will discuss the great deeds of Romulus, but cannot do so without bringing up one example first; someone whose similarly great deeds helped save Rome (3.2.1-2). This great man is Horatius Cocles. Valerius Maximus noted that he must next talk about another hero, Cloelia, after Horatius Cocles because they fight the same enemy, at the same time, at the same place, and both perform facta memorabilia to save Rome (3.2.2-3). Valerius Maximus mentioned Horatius Cocles and Cloelia together, as if they are a joined pair that cannot be separated. Yet there is another legendary figure, Mucius Scaevola, who also fights the same enemy, at the same time, and also performs facta memorabilia to save Rome. It is strange both that Valerius Maximus seemed compelled to unite Cloelia with the mention of Horatius Cocles, and also that he did not include Mucius Scaevola. Instead, Scaevola’s story is at the beginning of the next chapter (3.3.1). Traditionally these three heroes, Horatius Cocles, Cloelia, and Mucius Scaevola, were mentioned together by historians such as Livy and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, whose works predate Valerius Maximus’ (Ab Urbe Condita 2.10-13, Roman Antiquities 5.23-35). Valerius Maximus was able to split up the triad, despite the tradition, without receiving flack because it had already been done by Virgil in the Aeneid, where he described the dual images of Cocles and Cloelia on Aeneas’ shield, but Scaevola is absent (8.646-651). -

THE MARS ULTOR COINS of C. 19-16 BC

UNIWERSYTET ZIELONOGÓRSKI IN GREMIUM 9/2015 Studia nad Historią, Kulturą i Polityką s . 7-30 Victoria Győri King’s College, London THE MARS ULTOR COINS OF C. 19-16 BC In 42 BC Augustus vowed to build a temple of Mars if he were victorious in aveng- ing the assassination of his adoptive father Julius Caesar1 . While ultio on Brutus and Cassius was a well-grounded theme in Roman society at large and was the principal slogan of Augustus and the Caesarians before and after the Battle of Philippi, the vow remained unfulfilled until 20 BC2 . In 20 BC, Augustus renewed his vow to Mars Ultor when Roman standards lost to the Parthians in 53, 40, and 36 BC were recovered by diplomatic negotiations . The temple of Mars Ultor then took on a new role; it hon- oured Rome’s ultio exacted from the Parthians . Parthia had been depicted as a prime foe ever since Crassus’ defeat at Carrhae in 53 BC . Before his death in 44 BC, Caesar planned a Parthian campaign3 . In 40 BC L . Decidius Saxa was defeated when Parthian forces invaded Roman Syria . In 36 BC Antony’s Parthian campaign was in the end unsuccessful4 . Indeed, the Forum Temple of Mars Ultor was not dedicated until 2 BC when Augustus received the title of Pater Patriae and when Gaius departed to the East to turn the diplomatic settlement of 20 BC into a military victory . Nevertheless, Augustus made his Parthian success of 20 BC the centre of a grand “propagandistic” programme, the principal theme of his new forum, and the reason for renewing his vow to build a temple to Mars Ultor . -

La Latinità Di Ariccia E La Grecità Di Nemi. Istituzioni Civili E Religiose a Confronto

ANNA PASQUALINI La latinità di Ariccia e la grecità di Nemi. Istituzioni civili e religiose a confronto Il titolo del mio intervento è solo apparentemente contraddittorio. Esso è volto a mettere in relazione due contesti sociali tanto vicini nello spazio quanto distanti per impianto culturale e per funzioni politiche: la città di Ariccia e il lucus Dianius. Del bosco sacro a Diana e della selva che lo circonda si è scritto moltissimo soprattutto da quando esso costituì il fulcro di un’opera straordinaria per ricchezza ed originalità quale quella di Sir James Frazer1 Su Ariccia, invece, come comunità cittadina e sulle sue istituzioni politiche e religiose non si è riflettuto abbastanza2 e, in particolare, queste ultime non sono state messe sufficientemente in relazione con il santuario nemorense. Cercherò, quindi, di svolgere qualche considerazione nella speranza di fornire un piccolo contributo alla definizione degli intricati problemi del territorio aricino. Ariccia, come comunità politica, appare nelle fonti letterarie all’epoca del secondo Tarquinio, il tiranno per eccellenza, spregiatore del Senato e del popolo3. Al Superbo viene attribuita una forte vocazione al controllo politico del Lazio attraverso un’accorta rete di alleanze con i maggiorenti del Lazio, primo fra tutti il più eminente di essi, e cioè Ottavio Mamilio di Tuscolo, che è anche suo genero (Livio I 49); è ancora Tarquinio che, secondo le fonti (Livio I 50), indirizza la politica dei Latini convocando i federati in assemblea presso il lucus sacro a Ferentina4. La scelta del luogo non è casuale. Il bosco sacro è stato localizzato nel territorio di Ariccia, ma esso viene considerato idealmente collegato con il Monte Albano, cioè con il centro sacrale dei Latini, 1 La prima edizione dell’opera, The Golden Bough, risale al 1890. -

De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe Anne Truetzel

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2011 De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe Anne Truetzel Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Truetzel, Anne, "De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe" (2011). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 527. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/527 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Department of Classics De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe: Julius Caesar’s Influence on the Topography of the Comitium-Rostra-Curia Complex by Anne E. Truetzel A thesis presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts August 2011 Saint Louis, Missouri ~ Acknowledgments~ I would like to take this opportunity to thank the Classics department at Washington University in St. Louis. The two years that I have spent in this program have been both challenging and rewarding. I thank both the faculty and my fellow graduate students for allowing me to be a part of this community. I now graduate feeling well- prepared for the further graduate study ahead of me. There are many people without whom this project in particular could not have been completed. First and foremost, I thank Professor Susan Rotroff for her guidance and support throughout this process; her insightful comments and suggestions, brilliant ideas and unfailing patience have been invaluable. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

The Garter Room at Stowe House’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Michael Bevington, ‘The Garter Room at Stowe House’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XV, 2006, pp. 140–158 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2006 THE GARTER ROOM AT STOWE HOUSE MICHAEL BEVINGTON he Garter Room at Stowe House was described as the Ball Room and subsequently as the large Tby Michael Gibbon as ‘following, or rather Library, which led to a three-room apartment, which blazing, the Neo-classical trail’. This article will show Lady Newdigate noted as all ‘newly built’ in July that its shell was built by Lord Cobham, perhaps to . On the western side the answering gallery was the design of Capability Brown, before , and that known as the State Gallery and subsequently as the the plan itself was unique. It was completed for Earl State Dining Room. Next west was the State Temple, mainly in , to a design by John Hobcraft, Dressing Room, and the State Bedchamber was at perhaps advised by Giovanni-Battista Borra. Its the western end of the main enfilade. In Lady detailed decoration, however, was taken from newly Newdigate was told by ‘the person who shewd the documented Hellenistic buildings in the near east, house’ that this room was to be ‘a prodigious large especially the Temple of the Sun at Palmyra. Borra’s bedchamber … in which the bed is to be raised drawings of this building were published in the first upon steps’, intended ‘for any of the Royal Family, if of Robert Wood’s two famous books, The Ruins of ever they should do my Lord the honour of a visit.’ Palmyra otherwise Tedmor in the Desart , in . -

Tine Statue of Athena in the Parthenon

REMARKS UPON THE COLOSSALCHRYSELEPHAN- TINE STATUE OF ATHENA IN THE PARTHENON INTRODUCTION IT is not to be expectedthat even fragmentsof the gold and ivory colossal statue of Athena in the Parthenon should have survived the ravages of time. However, a good deal is known about the statue from small copies in the round and from coins, plaques, gems and the like; also, the famous statue is mentioned by ancient writers, sometimes at considerable length. Consequently we have a fairly good idea of her appearance. And when we come to consider the pedestal on which the statue stood, we find that there are data which can be studied to advantage. Obviously the importance of the statue called for a carefully designed pedestal. Thus it is desirable that all existing data concerning the pedestal be recorded. Let us, then, make a few remarks not only about the colossal statue, but also about the pedestal on which the statue stood. I ATHENA PARTHENOS, THE CLIMAX OF THE PANATHENEA Figure 1 shows the position of the colossal statue (often referred to as the Parthenos) in the east cella of the temple. The blocks which give the position of the statue are toward the west end of the nave and on the axis of the temple. They are poros blocks of the type used for foundations. They are flush with the marble pave- ment of the nave, and they are in situ. The poros blocks, thirty in number, cover an area so extensive that they at once tell us that the statue which stood above them was of colossal size (Figs. -

The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus

The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus ‘A thesis submitted to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy’ 2016 Jillian Mitchell For Michael – and in memory of my father Kenneth who started it all Abstract for PhD Thesis in Classics The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus This thesis explores the last decades of legal paganism in the Roman Empire of the second half of the fourth century CE through the eyes of Symmachus, orator, senator and one of the most prominent of the pagans of this period living in Rome. It is a religious biography of Symmachus himself, but it also considers him as a representative of the group of aristocratic pagans who still adhered to the traditional cults of Rome at a time when the influence of Christianity was becoming ever stronger, the court was firmly Christian and the aristocracy was converting in increasingly greater numbers. Symmachus, though long known as a representative of this group, has only very recently been investigated thoroughly. Traditionally he was regarded as a follower of the ancient cults only for show rather than because of genuine religious beliefs. I challenge this view and attempt in the thesis to establish what were his religious feelings. Symmachus has left us a tremendous primary resource of over nine hundred of his personal and official letters, most of which have never been translated into English. These letters are the core material for my work. I have translated into English some of his letters for the first time. -

To What Conjugation Do Compounds

2015 TSJCL Certamen Intermediate Division, Round 1 TU # 1: To what conjugation do compounds of the Latin verb d, dare belong? THIRD B1: What compound of d means 'give back'? REDD B2: What compound of d means 'hand over'? TRAD TU # 2: What is the nominative singular form of the noun whose accusative singular form is tempus? TEMPUS B1: For what type of nouns in Latin are the nominative and accusative forms always the same? NEUTER B2: What declensions have no neuter nouns? 1ST AND 5TH TU # 3: What in ancient Rome was the cursus honrum? A SEQUENCE OF POLITICAL/ELECTED OFFICES B1: What traditionally was the first office of the cursus? QUAESTOR B2: What office in the cursus came after consul? CENSOR TU # 4: What would you find out by listening to the rustling of the oak leaves at Dodona? YOUR FUTURE/FORTUNE B1: What deity would be telling you this information by way of the leaves? ZEUS B2: Where would you have to go to have the Pythia tell your future? DELPHI TU # 5: Listen carefully to the following passage, which I will read twice. Then answer in Latin the question that follows: "In for sunt mult homins. Sacerdots in templ precs offerunt. Serv togās et tunicās emunt. Pistrs panem vendunt. Lber inter s ludunt. Mercātrs sellās ostendunt. Fūrs pecuniam petunt. Mlits per omns ambulant et pacem servant." (repeat) Question: Qu cibum habent? PISTRS B1: Qu pecuniam habent? SERV B2: Qu nn labrant? LBER (score check) TU # 6: Where, since the second century AD, has been the best place to go in Rome to see relief carvings depicting people from the Roman province of Dacia? TRAJAN'S COLUMN B1: What country now occupies the land once called Dacia? ROMANIA B2: Name a building that Trajan built near his column.