Hutterite Colonies in Montana Map

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALEMANA GERMAN, ALEMÁN, ALLEMAND Language

ALEMANA GERMAN, ALEMÁN, ALLEMAND Language family: Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, German, Middle German, East Middle German. Language codes: ISO 639-1 de ISO 639-2 ger (ISO 639-2/B) deu (ISO 639-2/T) ISO 639-3 Variously: deu – Standard German gmh – Middle High german goh – Old High German gct – Aleman Coloniero bar – Austro-Bavarian cim – Cimbrian geh – Hutterite German kksh – Kölsch nds – Low German sli – Lower Silesian ltz – Luxembourgish vmf – Main-Franconian mhn – Mócheno pfl – Palatinate German pdc – Pennsylvania German pdt – Plautdietsch swg – Swabian German gsw – Swiss German uln – Unserdeutssch sxu – Upper Saxon wae – Walser German wep – Westphalian Glotolog: high1287. Linguasphere: [show] Beste izen batzuk (autoglotonimoa: Deutsch). deutsch alt german, standard [GER]. german, standard [GER] hizk. Alemania; baita AEB, Arabiar Emirerri Batuak, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgika, Bolivia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Brasil, Danimarka, Ekuador, Errumania, Errusia (Europa), Eslovakia, Eslovenia, Estonia, Filipinak, Finlandia, Frantzia, Hegoafrika, Hungaria, Italia, Kanada, Kazakhstan, Kirgizistan, Liechtenstein, Luxenburgo, Moldavia, Namibia, Paraguai, Polonia, Puerto Rico, Suitza, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Txekiar Errepublika, Txile, Ukraina eta Uruguain ere. Dialektoa: erzgebirgisch. Hizkuntza eskualde erlazionatuenak dira Bavarian, Schwäbisch, Allemannisch, Mainfränkisch, Hessisch, Palatinian, Rheinfränkisch, Westfälisch, Saxonian, Thuringian, Brandenburgisch eta Low saxon. Aldaera asko ez dira ulerkorrak beren artean. high -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Indian Commons, Privatization, Deprivatization, and Hutterites

Economic Evolution on the Northern Plains of the United States: Indian Commons, Privatization, Deprivatization, and Hutterites By John Baden and Jennifer Mygatt Foundation for Research on Economics and the Environment (FREE) June 2006 Introduction In Garrett Hardin’s 1968 “Tragedy of the Commons,” published in Science, Hardin argued that unmanaged commons lead to “ruin.” “Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons. Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.”1 Alternatives to an open- access commons include privatization, government-managed incentives (such as taxes and subsidies), and government land ownership through U.S. agencies such as the Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Reclamation, United States Forest Service, and the National Park Service. Political economists and economists almost always favor privatization.2 Over the last century and a half in the Great Plains of the United States, a combination of privatization and multi-veined government subsidy has resoundingly failed to produce a thriving society. And it is only getting worse. Here, we outline the history of European settlement on the Great Plains, from the 19th century to the present. We will focus on the history of the Plains as a commons, as well as environmental and social factors precluding successful European settlement there. We will address the demographic changes of the last two hundred years, and will finish with a successful case study illustrating the human ecology of niche filling. Locating the Great Plains The Great Plains lie west of the central lowlands and east of the Rocky Mountains. -

Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, German, Middle German, East Middle German

1 ALEMANA GERMAN, ALEMÁN, ALLEMAND Language family: Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, German, Middle German, East Middle German. Language codes: ISO 639-1 de ISO 639-2 ger (ISO 639-2/B) deu (ISO 639-2/T) ISO 639-3 Variously: deu – Standard German gmh – Middle High german goh – Old High German gct – Aleman Coloniero bar – Austro-Bavarian cim – Cimbrian geh – Hutterite German kksh – Kölsch nds – Low German sli – Lower Silesian ltz – Luxembourgish vmf – Main-Franconian mhn – Mócheno pfl – Palatinate German pdc – Pennsylvania German pdt – Plautdietsch swg – Swabian German gsw – Swiss German uln – Unserdeutssch sxu – Upper Saxon wae – Walser German wep – Westphalian Glotolog: high1287. Linguasphere: [show] 2 Beste izen batzuk (autoglotonimoa: Deutsch). deutsch alt german, standard [GER]. german, standard [GER] hizk. Alemania; baita AEB, Arabiar Emirerri Batuak, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgika, Bolivia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Brasil, Danimarka, Ekuador, Errumania, Errusia (Europa), Eslovakia, Eslovenia, Estonia, Filipinak, Finlandia, Frantzia, Hegoafrika, Hungaria, Italia, Kanada, Kazakhstan, Kirgizistan, Liechtenstein, Luxenburgo, Moldavia, Namibia, Paraguai, Polonia, Puerto Rico, Suitza, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Txekiar Errepublika, Txile, Ukraina eta Uruguain ere. Dialektoa: erzgebirgisch. Hizkuntza eskualde erlazionatuenak dira Bavarian, Schwäbisch, Allemannisch, Mainfränkisch, Hessisch, Palatinian, Rheinfränkisch, Westfälisch, Saxonian, Thuringian, Brandenburgisch eta Low saxon. Aldaera asko ez dira ulerkorrak beren artean. -

Advances in Hutterian Scholarship

Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies Volume 3 Issue 1 Special section: Education Article 8 2015 Advances in Hutterian Scholarship William L. Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/amishstudies Part of the Anthropology Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Smith, William L. 2015. "Advances in Hutterian Scholarship." Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies 3(1):124-29. This Review Essay is brought to you for free and open access by IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Review Essay Advances in Hutterian Scholarship Review of: Janzen, Rod, and Max Stanton. 2010. The Hutterites in North America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Review of: Katz, Yossi, and John Lehr. 2014[2012] Inside the Ark: The Hutterites in Canada and the United States [2nd ed.]. Regina, SK: University of Regina Press. By William L. Smith, Sociology, Georgia Southern University Certain elements of Hutterite life have changed significantly since the publication of Hutterian Brethren: The Agricultural Economy and Social Organization of a Communal People by John W. Bennett, Hutterite Society by John A. Hostetler, The Dynamics of Hutterite Society by Karl A. Peter, and The Hutterites in North America by John Hostetler and Gertrude Enders Huntington. -

Telling Stories (Out of School) of Mother Tongue, God's Tongue, and the Queen's Tongue: an Ethnography in Canada

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1991 Telling Stories (Out of School) of Mother Tongue, God's Tongue, and the Queen's Tongue: An Ethnography in Canada Joan Ratzlaff Swinney Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Swinney, Joan Ratzlaff, "Telling Stories (Out of School) of Mother Tongue, God's Tongue, and the Queen's Tongue: An Ethnography in Canada" (1991). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1240. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1239 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. TELLING STORIES (OUT OF SCHOOL) OF MOTHER TONGUE, GOD'S TONGUE, AND THE QUEEN'S TONGUE: AN ETHNOGRAPHY IN CANADA by JOAN RATZLAFF SWINNEY A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION In EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP Portland Stale University @1991 TO THE OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES: The members of tht! Committet! approve the disst!rtation of Joan Ratzlaff Swinney presented June 24, 1991. Strouse, Chair Robert B. Everhart William D. Grt!e~~ld APPROVED: Robert B. C. Willilllll Silvery, Vict! Provost for Gruduutt! Stutli : untl Rt!st!urch AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Joan IRatzlaff Swinney for the Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership pres.::nted June 24, 1991. Title: Telling Stories (Gut of School) of Mother TOllgue, God's TOllgue, and the Queen's Tongue: An Ethnography in Canarua APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE DISSERTATION COMMITTEE: Rohert B. -

Madison Jewish News 4

April 2017 Nisan 5777 A Publication of the Jewish Federation of Madison INSIDE THIS ISSUE Jewish Federation Upcoming Events ......................5 Lots of Fun at the Purim Carnival ....................14-15 Jewish Social Services....................................21-23 Simchas & Condolences ........................................6 Jewish Education ..........................................18-19 Israel & The World ........................................24-25 Congregation News ..........................................8-9 Business, Professional & Service Directory ............20 Camp Corner ....................................................27 My Life with Sir Nicholas Winton Renata Laxova, Professor Emerita at Force. Holocaust. the UW-Madison participated in a two- For the remainder of I happened to be one day celebration in memory of Sir his life, however, a single of the children from Nicholas Winton. Sir Nicholas, who died event forever occupied Nicky’s last Kindertrans- in 2015, organized eight Kindertrans- his mind. Having suc- port to arrive in Britain ports from Czechoslovakia in 1939, sav- cessfully organized the safely, (among only five ing the lives of hundreds of Jewish Czech safe arrival in London of with two surviving par- children, Dr. Laxova among them. Here eight Kindertransports, ents). It is my strong con- are some of her recollections, inspired totaling 669 children, he viction that not only I, but by the recent event. had arranged another— also both my parents, the ninth and largest owed our lives to Sir Save the Date BY DR. RENATA LAXOVA train, carrying 250 chil- Nicholas. My inclusion in dren—which was wait- the transport enabled my for Interfaith ing, prepared for parents to agree to sepa- I never actually met or spoke with departure, at the Prague Dr. Renata Laxova rate and hide, without him and our only direct contact lasted main railway station on having to worry about Advocacy Day! some thirty seconds out of his one hun- September 1, 1939, the day that Hitler me, their only child. -

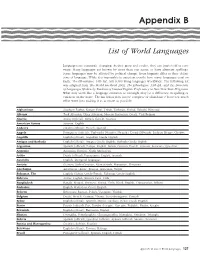

Bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages

Appendix B bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages Languages are constantly changing. As they grow and evolve, they can branch off or con- verge. Many languages are known by more than one name, or have alternate spellings. Some languages may be affected by political change. Even linguists differ in their defini- tions of language. While it is impossible to ascertain exactly how many languages exist on Earth, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., lists 6,809 living languages worldwide. The following list was adapted from The World Factbook 2002, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., and the Directory of Languages Spoken by Students of Limited English Proficiency in New York State Programs. What may seem like a language omission or oversight may be a difference in spelling or variation on the name. The list below may not be complete or all-inclusive; however, much effort went into making it as accurate as possible. Afghanistan Southern Pashto, Eastern Farsi, Uzbek, Turkmen, Brahui, Balochi, Hazaragi Albania Tosk Albanian, Gheg Albanian, Macedo-Romanian, Greek, Vlax Romani Algeria Arabic (official), French, Kabyle, Chaouia American Samoa Samoan, English Andorra Catalán (official), French, Spanish Angola Portuguese (official), Umbundu, Nyemba, Nyaneka, Loanda-Mbundu, Luchazi, Kongo, Chokwe Anguilla English (official), Anguillan Creole English Antigua and Barbuda English (official), Antigua Creole English, Barbuda Creole English Argentina Spanish (official), Pampa, English, Italian, German, French, Guaraní, Araucano, Quechua Armenia Armenian, Russian, North Azerbaijani -

The Hutterites in Canada and the United States by Yossi Katz and John Lehr Rod Janzen Fresno Pacific Nu Iversity

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Fall 2013 Review of Inside the Ark: The Hutterites in Canada and the United States by Yossi Katz and John Lehr Rod Janzen Fresno Pacific nU iversity Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Janzen, Rod, "Review of Inside the Ark: The Hutterites in Canada and the United States by Yossi Katz and John Lehr" (2013). Great Plains Quarterly. 2563. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2563 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 258 GREAT PLAINS QUARTERLY, FALL 2013 and 2009. But this is also problematic, limiting what can be said about Hutterite history and the diversity of beliefs and practices across the North American Hutterite community. In the short his torical section, for example, the Hutterites are described as "Christian perfectionists," which is somewhat confusing since the word "perfection ism" usually implies Christian theological under standings not associated with the Hutterites. Even more disconcerting is the fact that the book is not really a general study of all branches of the contemporary Hutterite community. Of the 50,000-plus Hutterites in North America, for example, nearly two-thirds are members of the of ten more conservative Lehrerleut and Dariusleut Inside the Ark: The Hutterites in Canada and the branches (whose colonies are located primarily United States. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. _______ In the Supreme Court of the United States __________ BIG SKY COLONY, INC., AND DANIEL E. WIPF, PETITIONERS v. MONTANA DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND INDUSTRY __________ ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF MONTANA __________ PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI __________ DOUGLAS LAYCOCK S. KYLE DUNCAN University of Virginia LUKE W. GOODRICH School of Law Counsel of Record 580 Massie Road ERIC C. RASSBACH Charlottesville, VA 22903 HANNAH C. SMITH JOSHUA D. HAWLEY RON A. NELSON DANIEL BLOMBERG MICHAEL P. TALIA The Becket Fund for Church, Harris, Religious Liberty Johnson & Williams 3000 K St., NW Ste. 220 114 3rd Street South Washington, DC 20007 Great Falls, MT 59403 (202) 955-0095 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioner QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether the Free Exercise Clause requires a plaintiff to demonstrate that the challenged law sin- gles out religious conduct or has a discriminatory mo- tive, as the First, Second, Fourth, and Eighth Cir- cuits and Montana Supreme Court have held, or whether it is instead sufficient to demonstrate that the challenged law treats a substantial category of nonreligious conduct more favorably than religious conduct, as the Third, Sixth, Tenth, and Eleventh Circuits and Iowa Supreme Court have held. 2. Whether the government regulates “an internal church decision” in violation of the Free Exercise Clause, Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church & School v. EEOC, 132 S. Ct. 694 (2012), when it forces a religious community to provide workers’ compensation insurance to its members in violation of the internal rules governing the commu- nity and its members. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form 1

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department off the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms { Type all entries complete applicable sections___ .__________ 1. Name historic TMr HistoricHi Hutterite Colonies Thematic 2. Location street & number multiple, see continuation sheets N/A not for publication city, town N/A- vicinity of congressional district state South Dakota code 45 county multiple code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied X agriculture museum _1_ building(s) X private Xf unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress X educational X private residence JLsite Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment X religious object N/A in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes; unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name multiple, see continuation sheets street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc, multiple, see continuation sheets street & number city, town state 6. Representation in Existing Surveys _______ title The Historic Hutt&rite Colonies Survey has this property been determined elegibie? yes _JL no date 19 79_______________________________ federal _JL state __county local depository for survey records Historical Preservation Center_________________________ city,town VernriTlion state South Dakota 57069 7. Description Condition Check one Check one X excellent X deteriorated X unaltered X original site X good _JL ruins _JL altered mnvpri riat<» fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The Hutterite Brethern live in eastern South Dakota in communal colonies, which are sited along the major water courses of the James, Big Sioux and Missouri Rivers and their tribu taries. -

Hutterite Colonies and the Cultural Landscape: an Inventory of Selected Site Characteristics

Hutterite Colonies and the Cultural Landscape: An Inventory of Selected Site Characteristics Simon M. Evans1 Adjunct Professor Department of Geography University of Calgary Peter Peller Head, Spatial and Numeric Data Services Libraries and Cultural Resources University of Calgary Abstract Hutterite colonies are a growing and sustainable element in the cultural landscape of the Canadian Prairies and Northern Great Plains of the United States. Their increasing numbers do something to offset the disappearance of the smallest service centers on the plains. While the diffusion of these communities has been well documented, the morphology of the settlements has been less well studied. New technology makes it possible to remotely evaluate selected characteristics of almost all Hutterite colonies. This paper describes the differences, with respect to orientation, layout and housing types, both between the four clan groups and within the Dariusleut and Schmiedeleut. Here as in many other aspects of Hutterite culture, there are signs of change and increasing diversity. Keywords Hutterite colonies; Cultural landscape; Google Earth; Orientation; Layout; Housing types; Dariusleut; Lehrerleut; Schmiedeleut; Great Plains Evans, Simon, and Peter Peller. 2016. “Hutterite Colonies and the Cultural Landscape: An Inventory of Selected Site Characteristics.” Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies 4(1):51-81. 52 Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies 4(1) Introduction Flying low from Calgary to Lethbridge, Alberta, and on to Great Falls, Montana, it is easy to pick out Hutterite colonies. Their relatively large and complex footprint is in marked contrast to that of neighbouring family farms. Colonies even show up clearly when viewed from the cruising altitude of a jet airliner.