Hutterite Colonies and the Cultural Landscape: an Inventory of Selected Site Characteristics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alberta the Co-Founders of Ribstone Creek Brewery Have Brought a Value-Added Business Back to the Village Where They Grew Up

Fighting Fires Jerusalem OUT HERE, when the artichoke has HOMECOMING HAS A water is Frozen Feed and bioFuel DIFFERENT potential MEANING. » PAGE 13 » PAGE 23 Livestock checklist now available in-store and at UFA.com. Publications Mail Agreement # 40069240 110201353_BTH_Earlug_AFE_v1.indd 1 2013-09-16 4:46 PM Client: UFA . Desiree File Name: BTH_Earlug_AFE_v1 Project Name: BTH Campaign CMYK PMS ART DIR CREATIVE CLIENT MAC ARTIST V1 Docket Number: 110201353 . 09/16/13 STUDIO Trim size: 3.08” x 1.83” PMS PMS COPYWRITER ACCT MGR SPELLCHECK PROD MGR PROOF # Volume 10, number 23 n o V e m b e r 1 1 , 2 0 1 3 Farmer brews up big business in rural Alberta The co-founders of Ribstone Creek Brewery have brought a value-added business back to the village where they grew up the recently completed ribstone Creek brewery still has plenty of room to expand brewing capacity. Photo: Jennifer Blair Vice-president Chris fraser had “they basically said to him, ‘You to expand once to meet growing By Jennifer Blair seen some craft breweries along really don’t know what you’re demand for its lager. af staff / edgerton his travels, and as soon as he sug- doing, do you?’ and we had to “It was a nice problem to have, “Nothing quite gets gested it, the four co-founders — admit that we didn’t,” Paré said. when your demand outweighs on Paré’s plan to build Paré, fraser, Ceo Cal Hawkes, and the supplier put the group your production,” said Paré. “But people’s attention like a brewery in the heart of Cfo alvin gordon — knew they in touch with brewmaster and unfortunately, it does hurt you, when you say the word D rural alberta came about had hit upon the right idea. -

Corporate Registry Registrar's Periodical

Service Alberta ____________________ Corporate Registry ____________________ Registrar’s Periodical SERVICE ALBERTA Corporate Registrations, Incorporations, and Continuations (Business Corporations Act, Cemetery Companies Act, Companies Act, Cooperatives Act, Credit Union Act, Loan and Trust Corporations Act, Religious Societies’ Land Act, Rural Utilities Act, Societies Act, Partnership Act) 0767527 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1209706 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2019 NOV 01 Registered Address: 300- Registered 2019 NOV 07 Registered Address: SUITE 10711 102 ST NW , EDMONTON ALBERTA, 230, 2323 32 AVE NE, CALGARY ALBERTA, T5H2T8. No: 2122266683. T2E6Z3. No: 2122278068. 0995087 B.C. INC. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1221996 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2019 NOV 14 Registered Address: 10012 - Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 3400, 350 101 STREET, PO BOX 6210, PEACE RIVER - 7TH AVENUE SW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P3N9. ALBERTA, T8S1S2. No: 2122287010. No: 2122268044. 10191787 CANADA INC. Federal Corporation 1221998 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2019 NOV 13 Registered Address: 4300 Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 3400, 350 BANKERS HALL WEST, 888 - 3RD STREET S.W., - 7TH AVENUE SW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P3N9. CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P 5C5. No: 2122287101. No: 2122268176. 102089241 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other 1221999 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 3400, 350 Registered Address: 101 - 1ST ST. EAST P.O. BOX - 7TH AVENUE SW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P3N9. 210, DEWBERRY ALBERTA, T0B 1G0. No: No: 2122268259. 2122270461. 1222024 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 10632449 CANADA LTD. Federal Corporation Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 3400, 350 Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 855 - 2 - 7TH AVENUE SW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P3N9. -

Hotspot You Would Like to Visit Within Beaver County Daysland Property

Cooking Lake-Blackfoot Provincial Recreation Area Parkland Natural Area For Tips and Etiquette Francis Viewpoint of Nature Viewing Click “i” Above Tofield Nature Center Beaverhill Bird Observatory Ministik Lake Game Bird Sanctuary Earth Academy Park Viking Bluebird Trails Black Nugget Lake Park Click on the symbol of the Camp Lake Park nature hotspot you would like to visit within Beaver County Daysland Property Viking Ribstones Prepared by Dr. Glynnis Hood, Dr. Glen Hvenegaard, Dr. Anne McIntosh, Wyatt Beach, Emily Grose, and Jordan Nakonechny in partnership with the University of Alberta All photos property of Jordan Nakonechny unless otherwise stated Augustana Campus and the County of Beaver Return to map Beaverhill Bird Observatory The Beaverhill Bird Observatory was established in 1984 and is the second oldest observatory for migration monitoring in Canada. The observatory possesses long-term datasets for the purpose of analyzing population trends, migration routes, breeding success, and survivorship of avian species. The observatory is located on the edge of Beaverhill Lake, which was designated as a RASMAR in 1987. Beaverhill Lake has been recognized as an Important Bird Area with the site boasting over 270 species, 145 which breed locally. Just a short walk from the laboratory one can commonly see or hear white-tailed deer, tree swallows, yellow warblers, house wrens, yellow-headed blackbirds, red- winged blackbirds, sora rails, and plains garter snakes. For more information and directions visit: http://beaverhillbirds.com/ Return to map Black Nugget Lake Park Black Nugget Lake Park contains a campground of well-treed sites surrounding a human-made lake created from an old coal mine. -

AMENDMENT 002 Attn: Sìne Macadam GETS Reference No

Title – Sujet RETURN BIDS TO: Cemetery Maintenance for Alberta RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date Veterans Affairs Canada 3000726188 2021-06-17 Procurement & Contracting – AMENDMENT 002 Attn: Sìne MacAdam GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG [email protected] - File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME Time Zone AMENDMENT - REQUEST FOR Fuseau horaire Solicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Atlantic Daylight PROPOSAL at – à 2:00 PM Time on – le 2021-06-29 ADT MODIFICATION - DEMANDE DE F.O.B. - F.A.B. PROPOSITION Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions Buyer Id – Id de l’acheteur à: Sìne MacAdam Proposal To: Veterans Affairs Canada Telephone No. – N° de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX (902) 626-5288 N/A We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: right of Canada, in accordance with the terms and Destination – des biens, services et construction : conditions set out herein, referred to herein or See Herein attached hereto, the goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. Proposition aux: Anciens Combattants Canada Nous offrons par la présente de vendre à Sa Majesté la Reine du chef du Canada, aux conditions énoncées ou incluses par référence dans la présente et aux annexes ci-jointes, les biens, services et construction énumérés ici sur toute feuille ci-annexées, au(x) prix indiqué(s) Instructions: See Herein Instructions : Voir aux présentes Delivery required - Delivered Offered – Livraison proposée Comments - Commentaires Livraison exigée See Herein Vendor/firm Name and address This requirement contains a security requirement Raison sociale et adresse du fournisseur/de l’entrepreneur Vendor/Firm Name and address Raison sociale et adresse du fournisseur/de l’entrepreneur Facsimile No. -

St2 St9 St1 St3 St2

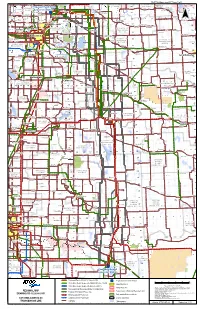

! SUPP2-Attachment 07 Page 1 of 8 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! .! ! ! ! ! ! SM O K Y L A K E C O U N T Y O F ! Redwater ! Busby Legal 9L960/9L961 57 ! 57! LAMONT 57 Elk Point 57 ! COUNTY ST . P A U L Proposed! Heathfield ! ! Lindbergh ! Lafond .! 56 STURGEON! ! COUNTY N O . 1 9 .! ! .! Alcomdale ! ! Andrew ! Riverview ! Converter Station ! . ! COUNTY ! .! . ! Whitford Mearns 942L/943L ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 56 ! 56 Bon Accord ! Sandy .! Willingdon ! 29 ! ! ! ! .! Wostok ST Beach ! 56 ! ! ! ! .!Star St. Michael ! ! Morinville ! ! ! Gibbons ! ! ! ! ! Brosseau ! ! ! Bruderheim ! . Sunrise ! ! .! .! ! ! Heinsburg ! ! Duvernay ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! 18 3 Beach .! Riviere Qui .! ! ! 4 2 Cardiff ! 7 6 5 55 L ! .! 55 9 8 ! ! 11 Barre 7 ! 12 55 .! 27 25 2423 22 ! 15 14 13 9 ! 21 55 19 17 16 ! Tulliby¯ Lake ! ! ! .! .! 9 ! ! ! Hairy Hill ! Carbondale !! Pine Sands / !! ! 44 ! ! L ! ! ! 2 Lamont Krakow ! Two Hills ST ! ! Namao 4 ! .Fort! ! ! .! 9 ! ! .! 37 ! ! . ! Josephburg ! Calahoo ST ! Musidora ! ! .! 54 ! ! ! 2 ! ST Saskatchewan! Chipman Morecambe Myrnam ! 54 54 Villeneuve ! 54 .! .! ! .! 45 ! .! ! ! ! ! ! ST ! ! I.D. Beauvallon Derwent ! ! ! ! ! ! ! STRATHCONA ! ! !! .! C O U N T Y O F ! 15 Hilliard ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! N O . 1 3 St. Albert! ! ST !! Spruce ! ! ! ! ! !! !! COUNTY ! TW O HI L L S 53 ! 45 Dewberry ! ! Mundare ST ! (ELK ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! . ! ! Clandonald ! ! N O . 2 1 53 ! Grove !53! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ISLAND) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ardrossan -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

Advances in Hutterian Scholarship

Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies Volume 3 Issue 1 Special section: Education Article 8 2015 Advances in Hutterian Scholarship William L. Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/amishstudies Part of the Anthropology Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Smith, William L. 2015. "Advances in Hutterian Scholarship." Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies 3(1):124-29. This Review Essay is brought to you for free and open access by IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Review Essay Advances in Hutterian Scholarship Review of: Janzen, Rod, and Max Stanton. 2010. The Hutterites in North America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Review of: Katz, Yossi, and John Lehr. 2014[2012] Inside the Ark: The Hutterites in Canada and the United States [2nd ed.]. Regina, SK: University of Regina Press. By William L. Smith, Sociology, Georgia Southern University Certain elements of Hutterite life have changed significantly since the publication of Hutterian Brethren: The Agricultural Economy and Social Organization of a Communal People by John W. Bennett, Hutterite Society by John A. Hostetler, The Dynamics of Hutterite Society by Karl A. Peter, and The Hutterites in North America by John Hostetler and Gertrude Enders Huntington. -

JOURNAL of ALBERTA POSTAL HISTORY Issue

JOURNAL OF ALBERTA POSTAL HISTORY Issue #22 Edited by Dale Speirs, Box 6830, Calgary, Alberta T2P 2E7, or [email protected] Published in February 2020. POSTAL HISTORY OF RED DEER RIVER BADLANDS: PART 2 by Dale Speirs This issue deals with the northern section of the Red Deer River badlands of south-central Alberta from Kneehill canyon to Rosedale. The badlands portion of the river stretches for 200 kilometres, gouged out by glacial meltwaters. The badlands are the richest source of Late Cretaceous dinosaurs in the world. Originally settled by homesteaders, the coal industry dominated from the 1920s to its death in the 1950s. Since then, the tourist industry has grown, with petroleum and agriculture strong. 2 Part 1 appeared in JAPH #13. Index To Post Offices. Aerial 44 Beynon 30 Cambria 47 Carbon 56 Drumheller 7 Fox Coulee 20 Gatine 51 Grainger 60 Hesketh 53 Midlandvale 13 Nacmine 17 Newcastle Mine 16 Rosebud Creek/Rosebud 33 Rosedale 40 Rosedale Station 40 Wayne 26 3 DRUMHELLER MUNICIPALITY The economic centre of the Red Deer River badlands is Drumheller, with a population of about 8,100 circa 2016. Below is a modern map of the area, showing Drumheller’s central position in the badlands. It began in 1911 as a coal mining village and grew rapidly during the heyday of coal. After World War Two, when railroads converted to diesel and buildings were heated with natural gas, Drumheller went into a decades-long decline. The economic slump was finally reversed by the construction of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, the world’s largest fossil museum and a major international tourist destination. -

Guide to Documents Relating to American Indians in Montana

Guide to Documents Relating to American Indians in Montana Identified and Collected by the Natives of Montana Archival Project (NOMAP) From Repositories in the National Archives and Records Administration, Smithsonian Institution & Library of Congress 2008-10 Helen Cryer (Saddle Lake Cree, ’08) Miranda McCarvel (’08-10) Carole Meyers (Oneida/Seneca/Blackfeet) (’10) Wilena Old Person (Blackfeet/Yakama, ’08-09) Glen Still Smoking Jr. (Blackfeet, ’08) Eli Suzukovich III (Cree, ’08) Richmond Clow (’10) David Beck, faculty advisor to project Steve McCann, Digital Projects Librarian Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………..... 2 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C. …........ 3 Record Group 75 Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) .... 3 Record Group 94, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office ……… 5 Record Group 217 Records of the Accounting Officers of the. Department of Treasury …………………………………...... 7 Record Group 393, Records of the U.S. Army Continental Commands, 1821-1920 ……………………………………... 7 National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland 8 Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives …………..... 9 NAA Manuscripts …………………………………………………. 9 NAA Audiotapes, Drawings, Films, Photographs and Prints ……... 20 Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of the American Indian Archives …………………………………………………….. 23 Library of Congress ……………………………………………………….. 26 Appendix 1: Key Word Index ...…………………………………………… 27 Appendix 2: Record Group 75 Entry 91 Letters Received Index …………. 41 1 Introduction This is a guide to primary source documents relating to Indians in Montana that are located in Washington D.C. These documents have been identified and in some cases digitized by teams of University of Montana students sponsored by the American Indian Programs of the National Museum of Natural History of the Smithsonian Institution and the UM Mansfield Library. -

Hutterite Colonies in Montana Map

Hutterite colonies in montana map Continue Three groups of Hutterites are located exclusively in the breadbasket or prairies of North America. Hutterites have subsisted almost entirely on agriculture since migrating to North America in 1874 which helps explain their geographical locations. All of Schmideleut's colonies are located in central North America, mainly in Manitoba and South Dakota. There are several colonies in North Dakota and Minnesota. Darius and Lehrer-leut are located in western North America, mainly in Saskatchewan, Alberta and Montana with spraying colonies in British Columbia, Washington and Oregon. Most colonies are located in Alberta (168), followed by Manitoba (107), Saskatchewan (60) and South Dakota (54). MB SK AB AB BC MT WA ND SD MN Totals Schmiedeleut 107 6 54 9 177 Dariusleut 29 98 2 15 5 1 149 Lehrerleut 1 31 69 35 135 Totals 107 60 168 2 50 5 5 54 9 462 A total of 462 colonies are scattered across the plains of North America. The total number of hutterites in NA hovers around 45,000. Approximately 75% of all Hutterites live in Canada, and the remaining 25% in the United States. The map below shows the distribution of Hutterite colonies in North America. Ethno-religious group since the 16th century; The community branch of the anabaptists HutteritesHutterite women at workTotal population50,000 (2020)FounderJacob HutterReligionsAnabaptistScripturesThe BibleLanguagesHutterite German, standard German, English Part of the series onAnabaptismDirk Willems (pictured) saves its pursuer. This act of mercy led to his -

Badlands Motorsports Resort

Badlands June Motorsports Resort 2013 [An innovative recreational resort for motorsport enthusiasts and Area families. Badlands Motorsports Resort proposes a self sustaining community that prides itself on creating a strong sense of belonging Structure within and around the resort and seamless integration of programs into the inherently surreal environment. ] Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................6 1.1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………….…………7 1.2 AREA STRUCTURE PLAN OBJECTIVES…………………………………………….................…………9 1.3 PLAN PREPARATION……………………………………..........…………………................………………9 1.4 PLAN INTERPRETATION……………………………………………………………...............……………….9 2 SITE ANALYSIS...........................................................................................................................10 2.1 LOCATION AND LANDSCAPE.......................................................................................10 2.2 GEOLOGY, HYDROLOGY, SOILS AND VEGETATION.....................................................11 2.2.1 Geology……………………………................................………………..………....…………11 2.2.2 Geomorphology.……………………………………………………………........…………………11 2.2.3 Hydrology…………………………………………………………………………….....………………11 2.2.4 Soils…….…………………………………………………………………………………….....…………14 2.2.5 Vegetation…….................………………………………………………………………......……14 2.3 WILDLIFE.....................................................................................................................17 -

Agricultural Service Board Agenda

AGRICULTURAL SERVICE BOARD AGENDA The Agricultural Service Board will hold a meeting on Monday, September 18, 2017, at 9:00 a.m., in Council Chambers, 1408 Twp Rd. 320, Didsbury, AB 1. AGENDA 1.1 Adoption of Agenda 2. ADOPTION OF MINUTES 2.1 Agricultural Service Board Meeting Minutes of August 21, 2017 3. BUSINESS ARISING OUT OF THE MINUTES 4. DELEGATION 4.1 9:00 a.m. Christine Campbell, ALUS Canada, Western Hub Manager (conference call - ALUS Update and Old Business 5.2) 4.2 9:30 a.m. Ryan Morrison, Assistant Directory of Operational Services Mountain View County (New Business 6.4) 4.3 10:00 a.m. Tammy Schwass, Alberta Plastics Recycling Association, Executive Director, Pat Sliworsky, CAO, Mountain View Regional Waste Management Commission & Patricia McKean, Mountain View County Division 2 / Vice Chair, Commission Board of Directors (Old Business 5.3) 4.4 11:00 a.m. Grant Lastiwka, Livestock / Forage Business Specialist for Alberta Agriculture and Forestry 5. OLD BUSINESS 5.1 Riparian and Ecological Enhancement Program Projects 5.2 Alternative Land Use Services (ALUS) Projects 5.3 Farm Plastic Round-Up Program Review 6. NEW BUSINESS 6.1 2018 ASB Projects Budget 6.2 Living in the Natural Environment Support 6.3 Wild Boar Agreement 6.4 Second Cut of Gravel Roads East of Highway 2 Discussion (verbal report) 7. INFORMATION ITEMS 7.1 a. Seed Plant Updates (verbal report) b. Upcoming Workshops - Mountain View County Events Webpage Link c. Aspen Ranch Farm Safety, Agricultural & Environmental Awareness (verbal report) d. On Farm Water Testing Request Form 7.2 Expense Form 8.