Pink Elephant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Famuan: October 2, 1986

This year, the Inde' owling team has as Coll. 0 :;a s heart set on NEWS ringing home the i ampionship. CAMPUS NOTES VSports 8 CLASSIFIEDS The Fal HEALTH THEVOCE*F LOIAAMUIEST 'an OPINIONS SPORTS VOL. 92 No. 15 / TALLAHASSEE, FLA. www.thefam an.com LIFESTYLES 9-12 - OCTOBER 23, 2000 - It's time FAMU defense saves the day By Andre Carter special teams units provided the Correspondent spark the struggling Rattlers needed again to after two straight losses. Florida A&M University radio The defense played a role in 28 of color commentator Mike Thomas the 42 points, including two defen- summed up FAMU's game against sive touchdowns. Turnovers set up represent the Norfolk State Spartans in 12 two more scores. They were seeking words. redemption after allowing 30 points "This has been a dominating per- versus North Carolina A&T last formance so far by this defensive week. They showed the same inten- unit," Thomas said during the first sity their coaches showed on the half. sidelines. In front of what was characterized After both teams started the game as a sparse crowd at Dick Price with three and outs of offense, cor- Stadium, FAMU defeated the nerback Troy Hart intercepted ANTOINE DAVIS Spartans 42-14. The Rattlers' record Spartan quarterback John Roberts moves to 6-2 overall and 5-1 in the and returned the ball to the Norfolk The Famuan/ Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference. State 5-yard line. Two plays later, Kea Dupree Editor's note: This column is While the offense started and stalled FAMU redeemed it's loss against the Aggies (above) with a running in the absence of SGA early in the game, the defense and Please see Game/ 8 42-14 victory over the Norfolk Spartans on Saturday. -

Skyline Orchestras

PRESENTS… SKYLINE Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, you’ll be viewing the band Skyline, led by Ross Kash. Skyline has been performing successfully in the wedding industry for over 10 years. Their experience and professionalism will ensure a great party and a memorable occasion for you and your guests. In addition to the music you’ll be hearing tonight, we’ve supplied a song playlist for your convenience. The list is just a part of what the band has done at prior affairs. If you don’t see your favorite songs listed, please ask. Every concern and detail for your musical tastes will be held in the highest regard. Please inquire regarding the many options available. Skyline Members: • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES…………………………..…….…ROSS KASH • VOCALS……..……………………….……………………………….….BRIDGET SCHLEIER • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..………….…………………….……VINCENT FONTANETTA • GUITAR………………………………….………………………………..…….JOHN HERRITT • SAXOPHONE AND FLUTE……………………..…………..………………DAN GIACOMINI • DRUMS, PERCUSSION AND VOCALS……………………………….…JOEY ANDERSON • BASS GUITAR, VOCALS AND UKULELE………………….……….………TOM MCGUIRE • TRUMPET…….………………………………………………………LEE SCHAARSCHMIDT • TROMBONE……………………………………………………………………..TIM CASSERA • ALTO SAX AND CLARINET………………………………………..ANTHONY POMPPNION www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 DANCE: 24K — BRUNO MARS A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY — FERGIE A SKY FULL OF STARS — COLD PLAY LONELY BOY — BLACK KEYS AIN’T IT FUN — PARAMORE LOVE AND MEMORIES — O.A.R. ALL ABOUT THAT BASS — MEGHAN TRAINOR LOVE ON TOP — BEYONCE BAD ROMANCE — LADY GAGA MANGO TREE — ZAC BROWN BAND BANG BANG — JESSIE J, ARIANA GRANDE & NIKKI MARRY YOU — BRUNO MARS MINAJ MOVES LIKE JAGGER — MAROON 5 BE MY FOREVER — CHRISTINA PERRI FT. ED SHEERAN MR. SAXOBEAT — ALEXANDRA STAN BEST DAY OF MY LIFE — AMERICAN AUTHORS NO EXCUSES — MEGHAN TRAINOR BETTER PLACE — RACHEL PLATTEN NOTHING HOLDING ME BACK — SHAWN MENDES BLOW — KE$HA ON THE FLOOR — J. -

Download Song List

Modern Dance 90’s, 00’s, 10’s Love Shack Juice Pour Some Sugar On Me Chain Of Fools Sucker You Shook Me All Night Long Soul Man The Middle Still The One In The Midnight Hour Feel It Still Kiss Gimme Some Lovin' 24K Magic Shake Your Body Down You Really Got Me Finesse I've Had The Time Of My Life Domino Shut Up And Dance Start Me Up Wild Night I Can’t Feel My Face The Power Of Love Brown Eyed Girl That’s What I Like Glory Days Moondance Shape Of You Jump! Proud Mary Uptown Funk All Night Long Born On A Bayou We Found Love Celebration Treasure Ladies Night 50’s Happy Don’t Stop Til You Get Enough Rock Around The Clock Downtown What I Like About You School Days Blurred Lines Crazy Little Thing Called Love All Shook Up This is How We Do It Sweet Caroline Hound Dog Can't Hold Us Play That Funky Music Jail House Rock Get Lucky Brick House Blue Suede Shoes Suit & Tie That’s The Way I Like It Johnny B. Goode Buzzin’ Get Down Tonight Rockin' Robin Call Me Maybe Night Fever Whole Lotta Shakin Forget You September Valerie We Are Family SLOW All I Do Is Win How Sweet It Is To Be Loved Perfect Moves Like Jagger Feelin' Alright Thinking Out Loud Party Rock Anthem Listen To The Music Like I’m Gonna Lose You DJ Got Us Falling In Love Crocodile Rock Speechless Raise Your Glass Dance The Night Away I Want It That Way California Gurls All Of Me Tik Tok 60’s Better Together Dynamite Pretty Woman At Last Empire State Of Mind Louie Louie Faithfully I Gotta Feelin La Bamba Wonderful Tonight Just Dance Ain’t No Mountain High Enough When A Man Loves A Woman Crazy -

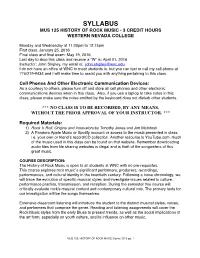

MUS 125 SYLLABUS(Spring 2016)

SYLLABUS MUS 125 HISTORY OF ROCK MUSIC - 3 CREDIT HOURS WESTERN NEVADA COLLEGE Monday and Wednesday at 11:00pm to 12:15pm First class: January 25, 2016 Final class and final exam: May 19, 2016 Last day to drop this class and receive a “W” is: April 01, 2016 Instructor: John Shipley, my email is: [email protected] I do not have an office at WNC to meet students in, but you can text or call my cell phone at 775/219-9434 and I will make time to assist you with anything pertaining to this class. Cell Phones And Other Electronic Communication Devices: As a courtesy to others, please turn off and store all cell phones and other electronic communications devices when in this class. Also, if you use a laptop to take notes in this class, please make sure the noise emitted by the keyboard does not disturb other students. *** NO CLASS IS TO BE RECORDED, BY ANY MEANS, WITHOUT THE PRIOR APPROVAL OF YOUR INSTRUCTOR. *** Required Materials: 1) Rock 'n Roll, Origins and Innovators by Timothy Jones and Jim McIntosh 2) A Pandora Apple Music or Spotify account or access to the music presented in class, i.e. your own or friend’s record/CD collection. Another resource is YouTube.com, much of the music used in this class can be found on that website. Remember downloading audio files from file sharing websites is illegal and is theft of the songwriters of this great music. COURSE DESCRIPTION: The History of Rock Music is open to all students at WNC with no pre-requisites. -

Songs by Artist

YouStarKaraoke.com Songs by Artist 602-752-0274 Title Title Title 1 Giant Leap 1975 3 Doors Down My Culture City Let Me Be Myself (Wvocal) 10 Years 1985 Let Me Go Beautiful Bowling For Soup Live For Today Through The Iris 1999 Man United Squad Loser Through The Iris (Wvocal) Lift It High (All About Belief) Road I'm On Wasteland 2 Live Crew The Road I'm On 10,000 MANIACS Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I M Gone Candy Everybody Wants Doo Wah Diddy When I'm Gone Like The Weather Me So Horny When You're Young More Than This We Want Some PUSSY When You're Young (Wvocal) These Are The Days 2 Pac 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Trouble Me California Love Landing In London 100 Proof Aged In Soul Changes 3 Doors Down Wvocal Somebody's Been Sleeping Dear Mama Every Time You Go (Wvocal) 100 Years How Do You Want It When You're Young (Wvocal) Five For Fighting Thugz Mansion 3 Doors Down 10000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Road I'm On Because The Night 2 Pac & Eminem Road I'm On, The 101 Dalmations One Day At A Time 3 LW Cruella De Vil 2 Pac & Eric Will No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 10CC Do For Love 3 Of A Kind Donna 2 Unlimited Baby Cakes Dreadlock Holiday No Limits 3 Of Hearts I'm Mandy 20 Fingers Arizona Rain I'm Not In Love Short Dick Man Christmas Shoes Rubber Bullets 21St Century Girls Love Is Enough Things We Do For Love, The 21St Century Girls 3 Oh! 3 Wall Street Shuffle 2Pac Don't Trust Me We Do For Love California Love (Original 3 Sl 10CCC Version) Take It Easy I'm Not In Love 3 Colours Red 3 Three Doors Down 112 Beautiful Day Here Without You Come See Me -

Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-2-2017 On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy Evan Nave Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Nave, Evan, "On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 697. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/697 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON MY GRIND: FREESTYLE RAP PRACTICES IN EXPERIMENTAL CREATIVE WRITING AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY Evan Nave 312 Pages My work is always necessarily two-headed. Double-voiced. Call-and-response at once. Paranoid self-talk as dichotomous monologue to move the crowd. Part of this has to do with the deep cuts and scratches in my mind. Recorded and remixed across DNA double helixes. Structurally split. Generationally divided. A style and family history built on breaking down. Evidence of how ill I am. And then there’s the matter of skin. The material concerns of cultural cross-fertilization. Itching to plant seeds where the grass is always greener. Color collaborations and appropriations. Writing white/out with black art ink. Distinctions dangerously hidden behind backbeats or shamelessly displayed front and center for familiar-feeling consumption. -

Please Note This Is a Sample Song List, Designed to Show the Style and Range of Music the Band Typically Performs

Please note this is a sample song list, designed to show the style and range of music the band typically performs. This is the most comprehensive list available at this time; however, the band is NOT LIMITED to the selections below. Please ask your event producer if you have a specific song request that is not listed. MSR SONG LIST TOP 40 AND DANCE HITS Adele Hello Rolling in the Deep Someone Like You Alicia Keys Underdog Andra Day Rise Up Ariana Grande 7 Rings Breathin Problems Thank You Next Beyonce Crazy in Love Halo Love on Top Single Ladies The Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Blink 182 All the Small Things Britney Spears Baby One More Time Bruno Mars 24K Magic Finesse Just the Way You Are Locked Out of Heaven That's What I Like Treasure Uptown Funk Cardi B I Like It Bodak Yellow Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe Calvin Harris This is What You Came For Camila Cabello Havana Cee Lo Green Forget You The Chainsmokers Closer Don’t Let Me Down Chris Brown Look at Me Now Clean Bandit Rather Be Echosmith Cool Kids Cupid Cupid Shuffle Daft Punk Get Lucky David Guetta Titanium Demi Lovato Neon Lights Desiigner Panda DNCE Cake by the Ocean Drake God’s Plan Hold on We're Going Home Hotline Bling One Dance Toosie Slide Ed Sheeran Perfect Shape of You Thinking Out Loud Ellie Goulding Burn Fetty Wap My Way Fifth Harmony Work from Home Flo Rida Low Ginuwine Pony Gnarls Barkley Crazy Gotye Somebody That I Used to Know Halsey Without Me Icona Pop I Love It Iggy Azalea Fancy Imagine Dragons Radioactive Jason Derulo Talk Dirty to Me The Other Side Want -

ASJ Song List Update.Pages

All Star Jukebox Song List 50's & 60's Rock & Soul 1. Ain't Too Proud To Beg (The Temptations) 2. Ain’t No Mountain High Enough (Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell) 3. Ain’t Nothin’ Like The Real Thing (Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell) 4. All Along the Watchtower (Bob Dylan) 5. All My Loving (The Beatles) 6. All You Need Is Love (The Beatles) 7. Bad Moon Rising (Creedence Clearwater Revival) 8. Blue Suede Shoes (Elvis Presley) 9. Burning Love (Elvis Presley) 10. Can’t Take My Eyes off of You (Frankie Valli & the Four Seasons) 11. Chain of Fools (Aretha Franklin) 12. Come Together (The Beatles) 13. Dancin' in the Streets (Martha & the Vandellas) 14. Dock of the Bay (Otis Redding) 15. Don’t Be Cruel (Elvis Presley) 16. Drive My Car (The Beatles) 17. Fire (Jimi Hendrix) 18. Get Back (The Beatles) 19. Get Ready Cause Here I Come 20. Gimme Some Lovin’ (Spencer Davis Band) 21. Good Lovin' (The Young Rascals) 22. Great Balls of Fire (Jerry Lee Lewis) 23. Hallelujah, I Love Her So (Ray Charles) 24. Happy Together (The Turtles) 25. Heard it Through the Grapevine (Marvin Gaye) 26. Here Comes the Sun (The Beatles) 27. Higher and Higher (Jackie Wilson) 28. Hound Dog (Elvis Presley) 29. I Can’t Help Falling in Love With You (Elvis Presley) 30. I Got You (James Brown) 31. Iko Iko (Dr. John) 32. I’m A Believer (The Monkees) 33. Imagine (John Lennon) 34. In My Life (The Beatles) 35. In the Midnight Hour (Wilson Picket) 36. I Saw Her Standing There (The Beatles) 37. -

How to Use This Songfinder

as of 3.14.2016 How To Use This Songfinder: We’ve indexed all the songs from 26 volumes of Real Books. Simply find the song title you’d like to play, then cross-reference the numbers in parentheses with the Key. For instance, the song “Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive” can be found in both The Real Book Volume III and The Real Vocal Book Volume II. KEY Unless otherwise marked, books are for C instruments. For more product details, please visit www.halleonard.com/realbook. 01. The Real Book – Volume I 10. The Charlie Parker Real Book (The Bird Book)/00240358 C Instruments/00240221 11. The Duke Ellington Real Book/00240235 B Instruments/00240224 Eb Instruments/00240225 12. The Bud Powell Real Book/00240331 BCb Instruments/00240226 13. The Real Christmas Book – 2nd Edition Mini C Instruments/00240292 C Instruments/00240306 Mini B Instruments/00240339 B Instruments/00240345 CD-ROMb C Instruments/00451087 Eb Instruments/00240346 C Instruments with Play-Along Tracks BCb Instruments/00240347 Flash Drive/00110604 14. The Real Rock Book/00240313 02. The Real Book – Volume II 15. The Real Rock Book – Volume II/00240323 C Instruments/00240222 B Instruments/00240227 16. The Real Tab Book – Volume I/00240359 Eb Instruments/00240228 17. The Real Bluegrass Book/00310910 BCb Instruments/00240229 18. The Real Dixieland Book/00240355 Mini C Instruments/00240293 CD-ROM C Instruments/00451088 19. The Real Latin Book/00240348 03. The Real Book – Volume III 20. The Real Worship Book/00240317 C Instruments/00240233 21. The Real Blues Book/00240264 B Instruments/00240284 22. -

Biography of James Brown from the Chapter Essay by Ricky Vincent

Biography of James Brown From the Chapter Essay by Ricky Vincent The most important force in the change in black music from blues based to rhythm-based music was James Brown. Brown’s 50-plus year career began in 1952 and lasted until his passing on Christmas Day 2006. Brown was known as “Soul Brother Number One” by fans who appreciated his intensely passionate delivery, his professionalism, and his close community connections. Born in a one-room shack in rural South Carolina, James Brown was raised by his aunts in Augusta, Georgia, who ran a brothel. There Brown learned first hand the nuances and necessities of the hustle, and Brown was soon on the streets of Augusta engaging in odd jobs, and eventually petty crimes and juvenile offenses. At the age of 16 Brown was caught stealing a coat from a car, and was given an eight year sentence. Upon his release in 1952 after only 3 years Brown stayed with the family of local singer Bobby Byrd, and joined Byrd’s group the Gospel Starlighters. Shortly after seeing the popularity of secular performance in the region, the group renamed itself the Famous Flames and performed a repertoire of rhythm and blues hits. Brown developed an appealing raw style that was popular throughout the South at the time. His first recording is now legendary, as the urgently begging ballad “Please, Please, Please” has been a part of his show for 50 years. The James Brown tour became the most celebrated R&B show on the circuit, with a show stopping performance, crisp, clean band and a number of stage antics, giveaways, raffles, and visits from local celebrities. -

Sing! 1975 – 2014 Song Index

Sing! 1975 – 2014 song index Song Title Composer/s Publication Year/s First line of song 24 Robbers Peter Butler 1993 Not last night but the night before ... 59th St. Bridge Song [Feelin' Groovy], The Paul Simon 1977, 1985 Slow down, you move too fast, you got to make the morning last … A Beautiful Morning Felix Cavaliere & Eddie Brigati 2010 It's a beautiful morning… A Canine Christmas Concerto Traditional/May Kay Beall 2009 On the first day of Christmas my true love gave to me… A Long Straight Line G Porter & T Curtan 2006 Jack put down his lister shears to join the welders and engineers A New Day is Dawning James Masden 2012 The first rays of sun touch the ocean, the golden rays of sun touch the sea. A Wallaby in My Garden Matthew Hindson 2007 There's a wallaby in my garden… A Whole New World (Aladdin's Theme) Words by Tim Rice & music by Alan Menken 2006 I can show you the world. A Wombat on a Surfboard Louise Perdana 2014 I was sitting on the beach one day when I saw a funny figure heading my way. A.E.I.O.U. Brian Fitzgerald, additional words by Lorraine Milne 1990 I can't make my mind up- I don't know what to do. Aba Daba Honeymoon Arthur Fields & Walter Donaldson 2000 "Aba daba ... -" said the chimpie to the monk. ABC Freddie Perren, Alphonso Mizell, Berry Gordy & Deke Richards 2003 You went to school to learn girl, things you never, never knew before. Abiyoyo Traditional Bantu 1994 Abiyoyo .. -

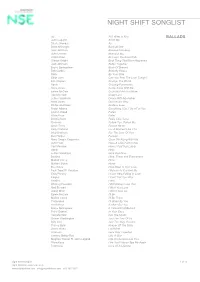

Night Shift Songlist

NIGHT SHIFT SONGLIST U2 All I Want Is You BALLADS John Legend All Of Me Stevie Wonder As Brian McKnight Back At One Jack Johnson Banana Pancakes John Lennon Beautiful Boy Celine Dion Because You Loved Me Gladys Knight Best Thing That Ever Happened Jack Johnson Better Together Bruce Springsteen Book Of Dreams Bob Carlisle Butterfly Kisses Sade By Your Side Elton John Can You Feel The Love Tonight Eric Clapton Change The World Adele Chasing Pavements Nora Jones Come Away With Me Edwin McCain Could Not Ask For More Van Morrison Crazy Love Luther Vandross Dance With My Father Nora Jones Don't Know Why Richie and Ross Endless Love Bryan Adams Everything I Do, I Do It For You Lauren Wood Fallen Alicia Keys Fallin' Bonnie Raitt Feels Like Home Genesis Follow You, Follow Me Steve Perry Foolish Heart Kelly Clarkson For A Moment Like This Isley Brothers For The Love Of You Ben Harper Forever Mary Chapin Carpenter Grow Old Along With Me John Hiatt Have A Little Faith In Me Van Morrison Have I Told You Lately Adele Hello Luther Vandross Here And Now Beatles Here, There and Everywhere Mariah Carey Hero Michael Buble Home Bee Gees How Deep Is Your Love Four Tops/W. Houston I Believe In You And Me Elvis Presley I Can't Help Falling In Love Eagles I Can't Tell You Why Beatles I Will Whitney Houston I Will Always Love You Rod Stewart I Wish You Love Jason Mraz I Won't Give Up Edwin McCain I'll Be Mariah Carey I'll Be There Pretenders I'll Stand By You Alicia Keys If I Ain't Got You Bruce Springsteen If I Should Fall Behind Peter Gabriel In Your Eyes Van Morrison Into The Mystic Grover Washington Just The Two Of Us Billy Joel Just The Way You Are Tracey Byrd Keeper Of The Stars Stevie Nicks Landslide Al Green Let's Stay Together Corinne Bailey Rae Like A Star Meghan Trainor Ft.