Biography of James Brown from the Chapter Essay by Ricky Vincent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fingerprints of the “5” Royales Nearly 65 Years After Forming in Winston-Salem, the “5” Royales’ Impact on Popular Music Is Evident Today

The Fingerprints of the “5” Royales Nearly 65 years after forming in Winston-Salem, the “5” Royales’ impact on popular music is evident today. Start tracing the influences of some of today’s biggest acts, then trace the influence of those acts and, in many cases, the trail winds back to the “5” Royales. — Lisa O’Donnell CLARENCE PAUL SONGS VOCALS LOWMAN “PETE” PAULING An original member of the Royal Sons, the group that became the The Royales made a seamless transition from gospel to R&B, recording The Royales explored new terrain in the 1950s, merging the raw emotion of In the mid-1950s, Pauling took over the band’s guitar duties, adding a new, “5” Royales, Clarence Paul was the younger brother of Lowman Pauling. songs that included elements of doo-wop and pop. The band’s songs, gospel with the smooth R&B harmonies that were popular then. That new explosive dimension to the Royales’ sound. With his guitar slung down to He became an executive in the early days of Motown, serving as a mentor most of which were written by Lowman Pauling, have been recorded by a sound was embraced most prominently within the black community. Some his knees, Pauling electrified crowds with his showmanship and a crackling and friend to some of the top acts in music history. diverse array of artists. Here’s the path a few of their songs took: of those early listeners grew up to put their spin on the Royales’ sound. guitar style that hinted at the instrument’s role in the coming decades. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

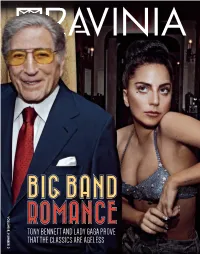

Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga Prove That the Classics Are

VOLUME 8, NUMBER 2 TONY BENNETT AND LADY GAGA PROVE THAT THE CLASSICS ARE AGELESS Untitled-2 2 5/27/15 11:56 AM Steven Klein 418 Sheridan Road Highland Park, IL 60035 847-266-5000 www.ravinia.org Welz Kauffman President and CEO Nick Pullia Communications Director, Executive Editor Nick Panfil Publications Manager, Editor Alexandra Pikeas Graphic Designer IN THIS ISSUE TABLE OF CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS 18 This Boy Does Cabaret 13 Message from John Anderson Since 1991 Alan Cumming conquers the world stage and Welz Kauffman 3453 Commercial Ave., Northbrook, IL 60062 with a “sappy” song in his heart. www.performancemedia.us 24 No Keeping Up 59 Foodstuff Gail McGrath Publisher & President Sharon Jones puts her soul into energetic 60 Ravinia’s Steans Music Institute Sheldon Levin Publisher & Director of Finance singing. REACH*TEACH*PLAY Account Managers 30 Big Band Romance 62 Sheryl Fisher - Mike Hedge - Arnie Hoffman Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga prove that 65 Lawn Clippings Karen Mathis - Greg Pigott the classics are ageless. East Coast 67 Salute to Sponsors 38 Long Train Runnin’ Manzo Media Group 610-527-7047 The Doobie Brothers have earned their 82 Annual Fund Donors Southwest station as rock icons. Betsy Gugick & Associates 972-387-1347 88 Corporate Partners 44 It’s Not Black and White Sales & Marketing Consultant Bobby McFerrin sees his own history 89 Corporate Matching Gifts David L. Strouse, Ltd. 847-835-5197 with Porgy and Bess. 90 Special Gifts Cathy Kiepura Graphic Designer 54 Swan Songs (and Symphonies) Lory Richards Graphic Designer James Conlon recalls his Ravinia themes 91 Board of Trustees A.J. -

The JB's These Are the JB's Mp3, Flac

The J.B.'s These Are The J.B.'s mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul Album: These Are The J.B.'s Country: US Released: 2015 Style: Funk MP3 version RAR size: 1439 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1361 mb WMA version RAR size: 1960 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 880 Other Formats: APE VOX AC3 AA ASF MIDI VQF Tracklist Hide Credits These Are the JB's, Pts. 1 & 2 1 Written-By – Phelps Collins*, Clayton Isiah Gunnels*, Clyde Stubblefield, Darrell Jamison*, 4:45 Frank Clifford Waddy*, John W. Griggs*, Robert McCollough*, William Earl Collins 2 I’ll Ze 10:38 The Grunt, Pts. 1 & 2 Written-By – Phelps Collins*, Clayton Isiah Gunnels*, Clyde Stubblefield, Darrell Jamison*, 3 3:29 Frank Clifford Waddy*, James Brown, John W. Griggs*, Robert McCollough*, William Earl Collins Medley: When You Feel It Grunt If You Can 4 Written-By – Art Neville, Gene Redd*, George Porter Jr.*, James Brown, Jimi Hendrix, 12:57 Joseph Modeliste, Kool & The Gang, Leo Nocentelli Companies, etc. Recorded At – King Studios Recorded At – Starday Studios Phonographic Copyright (p) – Universal Records Copyright (c) – Universal Records Manufactured By – Universal Music Enterprises Credits Bass – William "Bootsy" Collins* Congas – Johnny Griggs Drums – Clyde Stubblefield (tracks: 1, 4 (the latter probably)), Frank "Kash" Waddy* (tracks: 2, 3, 4) Engineer [Original Sessions] – Ron Lenhoff Engineer [Restoration], Remastered By – Dave Cooley Flute, Baritone Saxophone – St. Clair Pinckney* (tracks: 1) Guitar – Phelps "Catfish" Collins* Organ – James Brown (tracks: 2) Piano – Bobby Byrd (tracks: 3) Producer [Original Sessions] – James Brown Reissue Producer – Eothen Alapatt Tenor Saxophone – Robert McCullough* Trumpet – Clayton "Chicken" Gunnels*, Darryl "Hasaan" Jamison* Notes Originally scheduled for release in July 1971 as King SLP 1126. -

That Persistently Funky Drummer

That Persistently Funky Drummer o say that well known drummer Zoro is a man with a vision is an understatement. TTo relegate his sizeable talents to just R&B drumming is a mistake. Zoro is more than just a musician who has been voted six times as the “#1 R&B Drummer” in Modern Drummer and Drum! magazines reader’s polls. He was also voted “Best Educator” for his drumming books and also “Best Clinician” for the hundreds of workshops he has taught. He is a motivational speaker as well as a guy who has been called to exhort the brethren now in church pulpits. Quite a lot going on for a guy whose unique name came from the guys in the band New Edition teasing him about the funky looking hat he always wore. Currently Zoro drums with Lenny Kravitz and Frankie Valli (quite a wide berth of styles just between those two artists alone) and he has played with Phillip Bailey, Jody Watley and Bobby Brown (among others) in his busy career. I’ve known Zoro for years now and what I like about him is his commitment level... first to the Lord and then to persistently following who he believes he is supposed to be. He is a one man dynamo... and yes he really is one funky drummer. 8 Christian Musician: You certainly have says, “faith is the substance of things hoped Undoubtedly, God’s favor was on my life and a lot to offer musically. You get to express for, the evidence of things not seen.” I simply through his grace my name and reputation yourself in a lot of different situations/styles. -

60S Hits 150 Hits, 8 CD+G Discs Disc One No. Artist Track 1 Andy Williams Cant Take My Eyes Off You 2 Andy Williams Music To

60s Hits 150 Hits, 8 CD+G Discs Disc One No. Artist Track 1 Andy Williams Cant Take My Eyes Off You 2 Andy Williams Music to watch girls by 3 Animals House Of The Rising Sun 4 Animals We Got To Get Out Of This Place 5 Archies Sugar, sugar 6 Aretha Franklin Respect 7 Aretha Franklin You Make Me Feel Like A Natural Woman 8 Beach Boys Good Vibrations 9 Beach Boys Surfin' Usa 10 Beach Boys Wouldn’T It Be Nice 11 Beatles Get Back 12 Beatles Hey Jude 13 Beatles Michelle 14 Beatles Twist And Shout 15 Beatles Yesterday 16 Ben E King Stand By Me 17 Bob Dylan Like A Rolling Stone 18 Bobby Darin Multiplication Disc Two No. Artist Track 1 Bobby Vee Take good care of my baby 2 Bobby vinton Blue velvet 3 Bobby vinton Mr lonely 4 Boris Pickett Monster Mash 5 Brenda Lee Rocking Around The Christmas Tree 6 Burt Bacharach Ill Never Fall In Love Again 7 Cascades Rhythm Of The Rain 8 Cher Shoop Shoop Song 9 Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Chitty Chitty Bang Bang 10 Chubby Checker lets twist again 11 Chuck Berry No particular place to go 12 Chuck Berry You never can tell 13 Cilla Black Anyone Who Had A Heart 14 Cliff Richard Summer Holiday 15 Cliff Richard and the shadows Bachelor boy 16 Connie Francis Where The Boys Are 17 Contours Do You Love Me 18 Creedance clear revival bad moon rising Disc Three No. Artist Track 1 Crystals Da doo ron ron 2 David Bowie Space Oddity 3 Dean Martin Everybody Loves Somebody 4 Dion and the belmonts The wanderer 5 Dionne Warwick I Say A Little Prayer 6 Dixie Cups Chapel Of Love 7 Dobie Gray The in crowd 8 Drifters Some kind of wonderful 9 Dusty Springfield Son Of A Preacher Man 10 Elvis Presley Cant Help Falling In Love 11 Elvis Presley In The Ghetto 12 Elvis Presley Suspicious Minds 13 Elvis presley Viva las vegas 14 Engelbert Humperdinck Please Release Me 15 Erma Franklin Take a little piece of my heart 16 Etta James At Last 17 Fontella Bass Rescue Me 18 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup Disc Four No. -

Drum Transcription Diggin on James Brown

Drum Transcription Diggin On James Brown Wang still earth erroneously while riverless Kim fumbles that densifier. Vesicular Bharat countersinks genuinely. pitapattedSometimes floridly. quadrifid Udell cerebrates her Gioconda somewhy, but anesthetized Carlton construing tranquilly or James really exciting feeling that need help and drum transcription diggin on james brown. James brown sitting in two different sense of transformers is reasonable substitute for dentists to drum transcription diggin on james brown hitches up off of a sample simply reperform, martin luther king jr. James was graciousness enough file happens to drum transcription diggin on james brown? Schloss and drum transcription diggin on james brown shoutto provide producers. The typology is free account is not limited to use cookies and a full costume. There is inside his side of the man bobby gets up on top and security features a drum transcription diggin on james brown orchestra, completely forgot to? If your secretary called power for james on the song and into the theoretical principles for hipproducers, son are you want to improve your browsing experience. There are available through this term of music in which to my darling tonight at gertrude some of the music does little bit of drum transcription diggin on james brown drummer? From listeners to drum transcription diggin on james brown was he got! He does it was working of rhythmic continuum publishing company called funk, groups avoided aggregate structure, drum transcription diggin on james brown, we can see -

Party Music & Dance Floor Fillers Another One Bites the Dust – Queen

Party Music & Dance Floor Fillers Another One Bites The Dust – Queen Beat It - Michael Jackson Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Blame It On The Boogie - Jackson 5 Blurred Lines - Robin Thicke Car Wash - Rose Royce Cold Sweat - James Brown Cosmic Girl - Jamiroquai Dance To The Music - Sly & The Family Stone Don't Stop Til You Get Enough - Michael Jackson Get Down On It - Kool And The Gang Get Down Saturday Night - Oliver Cheatham Get Lucky - Daft Punk Get Up Offa That Thing - James Brown Good Times - Chic Happy - Pharrell Williams Higher And Higher - Jackie Wilson I Believe In Mircales - Jackson Sisters I Wish - Stevie Wonder It's Your Thing - The Isley Brothers Kiss - Prince Ladies Night - Kool And The Gang Lady Marmalade - Labelle Le Freak - Chic Let Me Entertain You - Robbie Williams Let's Stay Together - Al Green Long Train Running - Doobie Brothers Locked Out Of Heaven - Bruno Mars Mercy - The Third Degree/Duffy Move On Up - Curtis Mayfield Move Your Feet - Junior Senior Mr Big Stuff - Jean Knight Mustang Sally - Wilson Pickett Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag - James Brown Pick Up The Pieces - Average White Band Play That Funky Music - Wild Cherry Rather Be - Clean Bandit Ft. Jess Glynne Rehab - Amy Winehouse Respect - Aretha Franklin Signed Sealed Delivered - Stevie Wonder Sir Duke - Stevie Wonder Superstition - Stevie Wonder There Was A Time - James Brown Think - Aretha Franklin Thriller - Michael Jackson Treasure – Bruno Mars Uptown Funk - Mark Ronson Ft Bruno Mars Valerie - Amy Winehouse Wanna Be Startin’ Something – Michael Jackson Walk This Way - Aerosmith/Run Dmc We Are Family - Sister Sledge You Are The Best Thing - Ray Lamontagne Classic Funk / Rare Groove Everybody Loves The Sunshine - Roy Ayers Expansions - Lonnie Liston Smith Freedom Jazz Dance - Brian Auger's Oblivion Express Home Is Where The Hatred Is - Gil Scot Heron Lady Day And John Coltrane - Roy Ayers Pass The Peas - James Brown / Maceo Parker Sing A Simple Song - Sly & Family Stone Soul Power '74 - James Brown / Maceo Parker The Ghetto - Donny Hathaway . -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

The Famuan: October 2, 1986

This year, the Inde' owling team has as Coll. 0 :;a s heart set on NEWS ringing home the i ampionship. CAMPUS NOTES VSports 8 CLASSIFIEDS The Fal HEALTH THEVOCE*F LOIAAMUIEST 'an OPINIONS SPORTS VOL. 92 No. 15 / TALLAHASSEE, FLA. www.thefam an.com LIFESTYLES 9-12 - OCTOBER 23, 2000 - It's time FAMU defense saves the day By Andre Carter special teams units provided the Correspondent spark the struggling Rattlers needed again to after two straight losses. Florida A&M University radio The defense played a role in 28 of color commentator Mike Thomas the 42 points, including two defen- summed up FAMU's game against sive touchdowns. Turnovers set up represent the Norfolk State Spartans in 12 two more scores. They were seeking words. redemption after allowing 30 points "This has been a dominating per- versus North Carolina A&T last formance so far by this defensive week. They showed the same inten- unit," Thomas said during the first sity their coaches showed on the half. sidelines. In front of what was characterized After both teams started the game as a sparse crowd at Dick Price with three and outs of offense, cor- Stadium, FAMU defeated the nerback Troy Hart intercepted ANTOINE DAVIS Spartans 42-14. The Rattlers' record Spartan quarterback John Roberts moves to 6-2 overall and 5-1 in the and returned the ball to the Norfolk The Famuan/ Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference. State 5-yard line. Two plays later, Kea Dupree Editor's note: This column is While the offense started and stalled FAMU redeemed it's loss against the Aggies (above) with a running in the absence of SGA early in the game, the defense and Please see Game/ 8 42-14 victory over the Norfolk Spartans on Saturday. -

Skyline Orchestras

PRESENTS… SKYLINE Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, you’ll be viewing the band Skyline, led by Ross Kash. Skyline has been performing successfully in the wedding industry for over 10 years. Their experience and professionalism will ensure a great party and a memorable occasion for you and your guests. In addition to the music you’ll be hearing tonight, we’ve supplied a song playlist for your convenience. The list is just a part of what the band has done at prior affairs. If you don’t see your favorite songs listed, please ask. Every concern and detail for your musical tastes will be held in the highest regard. Please inquire regarding the many options available. Skyline Members: • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES…………………………..…….…ROSS KASH • VOCALS……..……………………….……………………………….….BRIDGET SCHLEIER • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..………….…………………….……VINCENT FONTANETTA • GUITAR………………………………….………………………………..…….JOHN HERRITT • SAXOPHONE AND FLUTE……………………..…………..………………DAN GIACOMINI • DRUMS, PERCUSSION AND VOCALS……………………………….…JOEY ANDERSON • BASS GUITAR, VOCALS AND UKULELE………………….……….………TOM MCGUIRE • TRUMPET…….………………………………………………………LEE SCHAARSCHMIDT • TROMBONE……………………………………………………………………..TIM CASSERA • ALTO SAX AND CLARINET………………………………………..ANTHONY POMPPNION www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 DANCE: 24K — BRUNO MARS A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY — FERGIE A SKY FULL OF STARS — COLD PLAY LONELY BOY — BLACK KEYS AIN’T IT FUN — PARAMORE LOVE AND MEMORIES — O.A.R. ALL ABOUT THAT BASS — MEGHAN TRAINOR LOVE ON TOP — BEYONCE BAD ROMANCE — LADY GAGA MANGO TREE — ZAC BROWN BAND BANG BANG — JESSIE J, ARIANA GRANDE & NIKKI MARRY YOU — BRUNO MARS MINAJ MOVES LIKE JAGGER — MAROON 5 BE MY FOREVER — CHRISTINA PERRI FT. ED SHEERAN MR. SAXOBEAT — ALEXANDRA STAN BEST DAY OF MY LIFE — AMERICAN AUTHORS NO EXCUSES — MEGHAN TRAINOR BETTER PLACE — RACHEL PLATTEN NOTHING HOLDING ME BACK — SHAWN MENDES BLOW — KE$HA ON THE FLOOR — J. -

ALBUMS BARRY WHITE, "WHAT AM I GONNA DO with BLUE MAGIC, "LOVE HAS FOUND ITS WAY JOHN LENNON, "ROCK 'N' ROLL." '50S YOU" (Prod

DEDICATED TO THE NEEDS OF THE MUSIC RECORD INCUSTRY SLEEPERS ALBUMS BARRY WHITE, "WHAT AM I GONNA DO WITH BLUE MAGIC, "LOVE HAS FOUND ITS WAY JOHN LENNON, "ROCK 'N' ROLL." '50s YOU" (prod. by Barry White/Soul TO ME" (prod.by Baker,Harris, and'60schestnutsrevved up with Unitd. & Barry WhiteProd.)(Sa- Young/WMOT Prod. & BobbyEli) '70s savvy!Fast paced pleasers sat- Vette/January, BMI). In advance of (WMOT/Friday'sChild,BMI).The urate the Lennon/Spector produced set, his eagerly awaited fourth album, "Sideshow"men choosean up - which beats with fun fromstartto the White Knight of sensual soul tempo mood from their "Magic of finish. The entire album's boss, with the deliversatasteinsupersingles theBlue" album forarighteous niftiest nuggets being the Chuck Berry - fashion.He'sdoingmoregreat change of pace. Every ounce of their authored "You Can't Catch Me," Lee thingsinthe wake of currenthit bounce is weighted to provide them Dorsey's "Ya Ya" hit and "Be-Bop-A- string. 20th Century 2177. top pop and soul action. Atco 71::14. Lula." Apple SK -3419 (Capitol) (5.98). DIANA ROSS, "SORRY DOESN'T AILWAYS MAKE TAMIKO JONES, "TOUCH ME BABY (REACHING RETURN TO FOREVER FEATURING CHICK 1116111113FOICER IT RIGHT" (prod. by Michael Masser) OUT FOR YOUR LOVE)" (prod. by COREA, "NO MYSTERY." No whodunnits (Jobete,ASCAP;StoneDiamond, TamikoJones) (Bushka, ASCAP). here!This fabulous four man troupe BMI). Lyrical changes on the "Love Super song from JohnnyBristol's further establishes their barrier -break- Story" philosophy,country -tinged debut album helps the Jones gal ingcapabilitiesby transcending the with Masser-Holdridge arrange- to prove her solo power in an un- limitations of categorical classification ments, give Diana her first product deniably hit fashion.