The Asclepian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Party Music & Dance Floor Fillers Another One Bites the Dust – Queen

Party Music & Dance Floor Fillers Another One Bites The Dust – Queen Beat It - Michael Jackson Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Blame It On The Boogie - Jackson 5 Blurred Lines - Robin Thicke Car Wash - Rose Royce Cold Sweat - James Brown Cosmic Girl - Jamiroquai Dance To The Music - Sly & The Family Stone Don't Stop Til You Get Enough - Michael Jackson Get Down On It - Kool And The Gang Get Down Saturday Night - Oliver Cheatham Get Lucky - Daft Punk Get Up Offa That Thing - James Brown Good Times - Chic Happy - Pharrell Williams Higher And Higher - Jackie Wilson I Believe In Mircales - Jackson Sisters I Wish - Stevie Wonder It's Your Thing - The Isley Brothers Kiss - Prince Ladies Night - Kool And The Gang Lady Marmalade - Labelle Le Freak - Chic Let Me Entertain You - Robbie Williams Let's Stay Together - Al Green Long Train Running - Doobie Brothers Locked Out Of Heaven - Bruno Mars Mercy - The Third Degree/Duffy Move On Up - Curtis Mayfield Move Your Feet - Junior Senior Mr Big Stuff - Jean Knight Mustang Sally - Wilson Pickett Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag - James Brown Pick Up The Pieces - Average White Band Play That Funky Music - Wild Cherry Rather Be - Clean Bandit Ft. Jess Glynne Rehab - Amy Winehouse Respect - Aretha Franklin Signed Sealed Delivered - Stevie Wonder Sir Duke - Stevie Wonder Superstition - Stevie Wonder There Was A Time - James Brown Think - Aretha Franklin Thriller - Michael Jackson Treasure – Bruno Mars Uptown Funk - Mark Ronson Ft Bruno Mars Valerie - Amy Winehouse Wanna Be Startin’ Something – Michael Jackson Walk This Way - Aerosmith/Run Dmc We Are Family - Sister Sledge You Are The Best Thing - Ray Lamontagne Classic Funk / Rare Groove Everybody Loves The Sunshine - Roy Ayers Expansions - Lonnie Liston Smith Freedom Jazz Dance - Brian Auger's Oblivion Express Home Is Where The Hatred Is - Gil Scot Heron Lady Day And John Coltrane - Roy Ayers Pass The Peas - James Brown / Maceo Parker Sing A Simple Song - Sly & Family Stone Soul Power '74 - James Brown / Maceo Parker The Ghetto - Donny Hathaway . -

Icons of Patience Memoir

ICONS OF PATIENCE The first lockdown Newcomers and Visiting Scholars writing project Newcomers and Visiting Scholars 1 ICONS OF PATIENCE The first lockdown Newcomers and Visiting Scholars writing project Now with hope of a vaccine on the horizon, this online publication documents thoughts, feelings and activities of our NVS contributors during the earlier stages of this 2020 Covid-19 pandemic. The range of lockdown conflicts and contradictions captured so sensitively by the individual voices of our members is striking: isolation yet friendship; confusion yet clarity; perseverance yet frustration; fear yet courage; sadness yet humour. Here are small delights in the shadow of darkness. When you look, read, or even listen, I hope you find the experience as uplifting as I did. My thanks go to Jane Luzio and Jenny McGuigan, who have helped every step of the way. I feel sure they will both agree that we can turn to this, a little history, really, in many years to come and say, “Look, this was where we were, what we did, what we thought and felt in the Spring of 2020. This is what we managed to get through…together.” Marianna Fletcher Williams November 2020 Foreword Many thanks, of course, to Marianna for being the inspiration for this wonderful project. NVS has always been a place where people from all over the world can come together to discuss, debate and express their thoughts and ideas. This record of the past year in poetry and prose is a true testament to that. Amanda Farnsworth NVS Chair Eric Whitacre’s Virtual Choir 6: Sing Gently https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=InULYfJHKI0 2 I Miss the Rain in Winter I miss the rain in winter, which is cold and damp. -

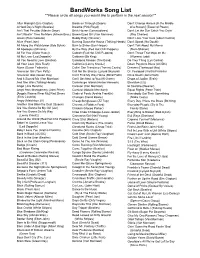

Bandworks Song List **Please Circle All Songs You Would Like to Perform in the Next Session**

BandWorks Song List **Please circle all songs you would like to perform in the next session** After Midnight (Eric Clapton) Break on Through (Doors) Don’t Change Horses [In the Middle A Hard Day’s Night (Beatles) Breathe (Pink Floyd) of a Stream] (Tower of Power) Ain’t That Peculiar (Marvin Gaye) Brick House (Commodores) Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Cryin’ Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More (Allman Bros.) Brown-Eyed Girl (Van Morrison) (Ray Charles) Alison (Elvis Costello) Buddy Holly (Weezer) Don’t Lose Your Cool (Albert Collins) Alive (Pearl Jam) Burning Down the House (Talking Heads) Don’t Speak (No Doubt) All Along the Watchtower (Bob Dylan) Burn to Shine (Ben Harper) Don’t Talk About My Mama All Apologies (Nirvana) By the Way (Red Hot Chili Peppers) (Mem Shanon) All For You (Sister Hazel) Cabron (Red Hot Chili Peppers) Don’t Throw That Mojo on Me All My Love (Led Zeppelin) Caldonia (Bb King) (Wynona Judd) All You Need Is Love (Beatles) Caledonia Mission (The Band) Do Your Thing (Lyn Collins) All Your Love (Otis Rush) California (Lenny Kravitz) Down Payment Blues (AC/DC) Alone (Susan Tedeschi) Callin’ San Francisco (Tommy Castro) Dreams (Fleetwood Mac) American Girl (Tom Petty) Call Me the Breeze (Lynyrd Skynyrd) Dr. Feelgood (Aretha Franklin) American Idiot (Green Day) Can’t Find My Way Home (Blind Faith) Drive South (John Hiatt) And It Stoned Me (Van Morrison) Can’t Get Next to You (Al Green) Drops of Jupiter (Train) And She Was (Talking Heads) Canteloupe Island (Herbie Hancock) Elevation (U2) Angel (Jimi Hendrix) Caravan (Van Morrison) -

Belles Lettres, 1941 Eastern Kentucky University, the Ac Nterbury Club

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Belles Lettres Literary Magazines 5-1-1941 Belles Lettres, 1941 Eastern Kentucky University, The aC nterbury Club Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/upubs_belleslettres Recommended Citation Eastern Kentucky University, The aC nterbury Club, "Belles Lettres, 1941" (1941). Belles Lettres. Paper 7. http://encompass.eku.edu/upubs_belleslettres/7 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the Literary Magazines at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Belles Lettres by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A *>iy <> \u\ *>l> An annual anthology of student writing sponsored and published by the Canterbury Club of Eastern Kentucky State Teachers College at Richmond, Kentucky Editor Mary Agnes Finneran Associate Editor , Vera Maybury Business Manager Raymond Goodlett Faculty Sponsor Roy B. Clark, Ph. D. VOLUME SEVEN NINETEEN FORTY-ONE ©onteniD When I Dare To Think Ruth Catlett 3 Epitome Dock Chandler 4 Full Life James Brock 4 Death Sleep Harold McConnell 5 Time, a Bandit Vera Maybury 7 There's Beauty Still Rhoda Whitehouse 8 Pillar of Society Paul Brandes 9 Meditation Helen Bowling 14 Death Took You Yesterday .... Betty Jo Weaver 15 Fog Helen Ashcraft 16 Strings Orville Byrne 16 Poor Tom's a-Cold Emma Osborne 16 My Mother Paul Brandes 18 In the Bus Station Ann Thomas 19 The Veteran Barney Be Jarnette 20 Life Helen Ashcraft 22 Recompense Helen Klein 22 A Maid and Her Mark Paul Brandes 25 The Graveyard Robert Witt, Jr 26 Grandmother Vera Maybury 26 Alone Emma Sams 28 FOREWORD With a feeling of gratitude for the in- creased interest the public is showing in Belles Lettres, the editors present this year's volume (1941). -

The Top 200 Greatest Funk Songs

The top 200 greatest funk songs 1. Get Up (I Feel Like Being a Sex Machine) Part I - James Brown 2. Papa's Got a Brand New Bag - James Brown & The Famous Flames 3. Thank You (Falletinme Be Mice Elf Agin) - Sly & The Family Stone 4. Tear the Roof Off the Sucker/Give Up the Funk - Parliament 5. Theme from "Shaft" - Isaac Hayes 6. Superfly - Curtis Mayfield 7. Superstition - Stevie Wonder 8. Cissy Strut - The Meters 9. One Nation Under a Groove - Funkadelic 10. Think (About It) - Lyn Collins (The Female Preacher) 11. Papa Was a Rollin' Stone - The Temptations 12. War - Edwin Starr 13. I'll Take You There - The Staple Singers 14. More Bounce to the Ounce Part I - Zapp & Roger 15. It's Your Thing - The Isley Brothers 16. Chameleon - Herbie Hancock 17. Mr. Big Stuff - Jean Knight 18. When Doves Cry - Prince 19. Tell Me Something Good - Rufus (with vocals by Chaka Khan) 20. Family Affair - Sly & The Family Stone 21. Cold Sweat - James Brown & The Famous Flames 22. Out of Sight - James Brown & The Famous Flames 23. Backstabbers - The O'Jays 24. Fire - The Ohio Players 25. Rock Creek Park - The Blackbyrds 26. Give It to Me Baby - Rick James 27. Brick House - The Commodores 28. Jungle Boogie - Kool & The Gang 29. Shining Star - Earth, Wind, & Fire 30. Got To Give It Up Part I - Marvin Gaye 31. Keep on Truckin' Part I - Eddie Kendricks 32. Dazz - Brick 33. Pick Up the Pieces - Average White Band 34. Hollywood Singing - Kool & The Gang 35. Do It ('Til You're Satisfied) - B.T. -

AP Literature and Composition

Pearson Education AP* Test Prep Series AP Literature and Composition Steven F. Jolliffe Richard McCarthy St. Johnsbury Academy *Advanced Placement, Advanced Placement Program, AP, and Pre-AP are registered trademarks of the College Board, which was not involved in the production of, and does not endorse, these products. Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco Upper Saddle River Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montreal Toronto Delhi Mexico City Sao Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo Vice President and Editor-in-Chief: Joseph Terry Senior Acquisitions Editor: Vivian Garcia Development Editor: Erin Reilly Senior Supplements Editor: Donna Campion Production Project Manager: Teresa Ward Production Management and Composition: Grapevine Publishing Services Cover Production: Alison Barth Burgoyne Manufacturing Buyer: Roy Pickering Executive Marketing Manager: Alicia Orlando Text and Cover Printer: Edwards Brothers Copyright © 2012 by Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. This publication is protected by Copyright and permission should be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction, storage in a retrieval system, or transmission in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or likewise. To obtain permission(s) to use material from this work, please submit a written request to Pearson Education, Inc., Permissions Department, 1900 E. Lake Ave., Glenview, IL 60025. For information regarding permissions, call (847) 486-2635. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designa- tions appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial caps or all caps. -

Biography of James Brown from the Chapter Essay by Ricky Vincent

Biography of James Brown From the Chapter Essay by Ricky Vincent The most important force in the change in black music from blues based to rhythm-based music was James Brown. Brown’s 50-plus year career began in 1952 and lasted until his passing on Christmas Day 2006. Brown was known as “Soul Brother Number One” by fans who appreciated his intensely passionate delivery, his professionalism, and his close community connections. Born in a one-room shack in rural South Carolina, James Brown was raised by his aunts in Augusta, Georgia, who ran a brothel. There Brown learned first hand the nuances and necessities of the hustle, and Brown was soon on the streets of Augusta engaging in odd jobs, and eventually petty crimes and juvenile offenses. At the age of 16 Brown was caught stealing a coat from a car, and was given an eight year sentence. Upon his release in 1952 after only 3 years Brown stayed with the family of local singer Bobby Byrd, and joined Byrd’s group the Gospel Starlighters. Shortly after seeing the popularity of secular performance in the region, the group renamed itself the Famous Flames and performed a repertoire of rhythm and blues hits. Brown developed an appealing raw style that was popular throughout the South at the time. His first recording is now legendary, as the urgently begging ballad “Please, Please, Please” has been a part of his show for 50 years. The James Brown tour became the most celebrated R&B show on the circuit, with a show stopping performance, crisp, clean band and a number of stage antics, giveaways, raffles, and visits from local celebrities. -

Filibuster 2008

Filibuster 2008 Writing a book is an adventure. To begin with, it is a toy and an amusement. Then it becomes a mistress, then it becomes a master, then it becomes a tyrant. The last phase is that just as you are about to be reconciled to your servitude, you kill the monster, and fling him to the public. Sir Winston Churchill Directly From the Editor!! Friends, full fraught with war-sweat glaring, kismet-dashed with derring-do, doth here present case: Alas the day when all voices cease and the final hours of coiling conundrum crash all together like minute pawns against the wagerly knights and evening kings and kingly queens in furious disparagement dispatch- ing the last breaths of mighty air! Not really. So, as both an editor and a writer, my chiefest frustration is also the greatest gift: I’m not included in this issue! “Humbug!” says Scrooge; “Hilarious!” says I! Aye. The focus changes when a feverish brain must reach for words other than its own, and here presented is the fruit of my labor(ers). No, I didn’t hire a score of goblins to sit in a dungeon and swim through page after page of unfaltering text. No. I swam through page after page, and one of the hardest things an editor must, MUST, do is say “No” to someone. I had to turn down some submissions. Sounding the trumpet from the blistering recesses of the computer lab to the towering heights of the Library’s tenth floor yielded a great wealth of submissions, for which I among others am thoroughly grateful. -

Polydor Records Discography 3000 Series

Polydor Records Discography 3000 series 25-3001 - Emergency! - The TONY WILLIAMS LIFETIME [1969] (2xLPs) Emergency/Beyond Games//Where/Vashkar//Via The Spectrum Road/Spectrum//Sangria For Three/Something Special 25-3002 - Back To The Roots - JOHN MAYALL [1971] (2xLPs) Prisons On The Road/My Children/Accidental Suicide/Groupie Girl/Blue Fox//Home Again/Television Eye/Marriage Madness/Looking At Tomorrow//Dream With Me/Full Speed Ahead/Mr. Censor Man/Force Of Nature/Boogie Albert//Goodbye December/Unanswered Questions/Devil’s Tricks/Travelling PD 2-3003 - Revolution Of The Mind-Live At The Apollo Volume III - JAMES BROWN [1971] (2xLPs) Bewildered/Escape-Ism/Get Up, Get Into It, Get Involved/Get Up I Feel Like Being A Sex Machine/Give It Up Or Turnit A Loose/Hot Pants (She Got To Use What She Got To Need What She Wants)/I Can’t Stand It/I Got The Feelin’/It’s A New Day So Let A Man Come In And Do The Popcorn/Make It Funky/Mother Popcorn (You Got To Have A Mother For Me)/Soul Power/Super Bad/Try Me [*] PD 2-3004 - Get On The Good Foot - JAMES BROWN [1972] (2xLPs) Get On The Good Foot (Parts 1 & 2)/The Whole World Needs Liberation/Your Love Was Good For Me/Cold Sweat//Recitation (Hank Ballard)/I Got A Bag Of My Own/Nothing Beats A Try But A Fail/Lost Someone//Funky Side Of Town/Please, Please//Ain’t It A Groove/My Part-Make It Funky (Parts 3 & 4)/ Dirty Harri PD 2-3005 - Ten Years Are Gone - JOHN MAYALL [1973] (2xLPs) Ten Years Are Gone/Driving Till The Break Of Dawn/Drifting/Better Pass You By//California Campground/Undecided/Good Looking -

Living with Atrial Fibrillation (Afib): Introduction

LIVING WITH ATRIAL FIBRILLATION Patient Guide University of North Carolina Department of Cardiology and Electrophysiology 1 Living with Atrial Fibrillation TABLE OF CONTENTS Living with Atrial Fibrillation (Afib): Introduction ......................................................... 3 Overview of Atrial Fibrillation .......................................................................................... 5 Who gets Afib? ...........................................................................................................................7 Types of Afib- What Type Do You Have? ................................................................................7 What Are Symptoms of Afib? ...................................................................................................8 What are the Dangers of Afib? ..................................................................................................8 Diagnosis of Afib ........................................................................................................................9 Afib Treatment .......................................................................................................................... 10 Important Points If You Are Taking Blood Thinners ............................................................ 11 Common Medications For Heart Rate Control in Afib ......................................................... 13 Getting The Heart back In Normal Rhythm: .......................................................................... 14 Antiarrhythmic -

AC/DC ADELE Rolling in the Deep Someone Like You AL GREEN

AC/DC BOZ SCAGGS CHRISTINA AGUILERA You Shook Me All Night Long Lido Shuffle Ain’t No Other Man ADELE CHUCK MANGIONE Rolling in the Deep Feels So Good Someone Like You COMMODORES AL GREEN Brick House Let’s Stay Together Easy AL JERREAU CREEDENCE Boogie Down CLEARWATER REVIVAL Proud Mary ALICIA KEYS If I Ain’t Got You CUPID Cupid Shuffle ARETHA FRANKLIN Chain of Fools DAFT PUNK Freeway of Love Get Lucky Respect DELBERT McCLINTON AVERAGE WHITE BAND Goin’ Back To Louisiana Pick up the Pieces DONNA SUMMER BEATLES BON JOVI Last Dance Got to Get You into My Life Livin’ on a Prayer In My Life EARTH WIND AND FIRE BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN Got to Get You In to My Life BEYONCÉ Born to Run In the Stone Crazy in Love Dancing in the Dark Let’s Groove Déjà vu September Love On Top BRUNO MARS Shining Star Run Away Baby BILLY JOEL Lazy Song EDDIE MONEY Just the Way Take Me Home Tonight Left Out of Heaven BILLY OCEAN Treasure ELTON JOHN Caribbean Queen Your Song CHEAP TRICK BOB MARLEY I Want You to Want Me ETTA JAMES Three Little Birds At Last CHICAGO Steal Away BOBBY CALDWELL Beginnings What You Won’t Do for Love Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is? EURYTHMICS Saturday in the Park Sweet Dreams Make Me Smile FELICIA SANDERS Fly Me to the Moon JOURNEY LOUIS ARMSTRONG Don’t Stop Believing What a Wonderful World FRANK SINATRA Separate Ways World on a String LUMINEERS New York New York KATRINA AND THE Ho Hey WAVES FRANKIE VALLEY Walking on Sunshine MACK RICE & THE FOUR SEASONS Mustang Sally Can’t Take My Eyes off of You KATY PERRY Oh What A Night Hot ‘N Cold -

The Winonan - 1940S

Winona State University OpenRiver The inonW an - 1940s The inonW an – Student Newspaper 3-29-1946 The inonW an Winona State Teachers' College Follow this and additional works at: https://openriver.winona.edu/thewinonan1940s Recommended Citation Winona State Teachers' College, "The inonW an" (1946). The Winonan - 1940s. 58. https://openriver.winona.edu/thewinonan1940s/58 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The inonW an – Student Newspaper at OpenRiver. It has been accepted for inclusion in The inonW an - 1940s by an authorized administrator of OpenRiver. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The358 ENTERED AS SECOND CLASS MATTER, WINONA, MINN. VoL. XX VII WINONA STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE, WINONA, MINNESOTA, MARCH 29, 1946 No. 7 Art Club Plans Wenonah Players . To Give "Blithe Spirit" For Spring Prom Noel Coward Farce Near Completion Plans are now being completed Judged Hilarious; by the members of the Art Club for the annual spring Prom to be Nelson Plays Lead held April 27. Carrol DeWald, president of the club, is the gen- "Blithe Spirit," a three-act im- eral chairman in charge of ar- probable farce by Noel Coward, rangements and committees. will be produced by the Wenonah Otto Stock and his orchestra Players on Saturday, May 4, ac- will furnish the music for the cording to an announcement by formal date affair, dancing to be Miss Dorothy B. Magnus, di- held in Somsen gym. Tickets for rector. the dance will go on sale begin- Noel Coward's play is one of ning April 8. the ten best plays, according to critics, produced on Broadway in the last six years.