The Poetry of Bob Kaufman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ishmael Reed Interviewed

Boxing on Paper: Ishmael Reed Interviewed by Don Starnes [email protected] http://www.donstarnes.com/dp/ Don Starnes is an award winning Director and Director of Photography with thirty years of experience shooting in amazing places with fascinating people. He has photographed a dozen features, innumerable documentaries, commercials, web series, TV shows, music and corporate videos. His work has been featured on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Comedy Central, HBO, MTV, VH1, Speed Channel, Nerdist, and many theatrical and festival screens. Ishmael Reed [in the white shirt] in New Orleans, Louisiana, September 2016 (photo by Tennessee Reed). 284 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10. no.1, March 2017 Editor’s note: Here author (novelist, essayist, poet, songwriter, editor), social activist, publisher and professor emeritus Ishmael Reed were interviewed by filmmaker Don Starnes during the 2014 University of California at Merced Black Arts Movement conference as part of an ongoing film project documenting powerful leaders of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements. Since 2014, Reed’s interview was expanded to take into account the presidency of Donald Trump. The title of this interview was supplied by this publication. Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) is the winner of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (genius award), the renowned L.A. Times Robert Kirsch Lifetime Achievement Award, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the National Institute for Arts and Letters. He has been nominated for a Pulitzer and finalist for two National Book Awards and is Professor Emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley (a thirty-five year presence); he has also taught at Harvard, Yale and Dartmouth. -

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

2018–2019 Annual Report the Center for the Humanities

The Center for the Humanities for The Center The Center for the Humanities The Center for the The Graduate Center, CUNY 365 5th Ave., Room 5103 New York, NY 10016 Humanities 2018-2019 2018–2019 Annual Report 2 3 4 Letter from the Director 6 Letter from the Staff 11 Student Engagement 29 Faculty Engagement 51 Public Engagement 75 Statistics 80 About the Center Front cover: Rachel Mazique presents at "Publishing American Sign Language Poetry," 2018. Participants at "Listening with Radical Empathy," 2018. Top: Hawwaa Ibrahim presents the keynote at the Y.E.S. Youth Summit, 2018. for the Humanities Bottom: Installation view of Ellen Rothenberg, "ISO 6346: ineluctable immigrant," 2019. 4 5 Letter from the Director The Center for the Humanities has been serving its various constit- uencies for a quarter century, and to commemorate our milestone year, we have chosen to arrange this annual report by celebrating the people we work with, demonstrating the variety of ways we collaborate with researchers—from individual students, faculty members, and visitors to community groups and global organizations. Over the last academic year, the Center for the Humanities has concentrated its energies on initiating, developing, and promoting sustained bodies of research over time. These discrete projects comprise an increasing part of our work. Moving away from delivering one-off events and conferences and toward supporting integrated multidisciplinary research, the Center has initiated collaborations with an increasingly diverse range of partner organizations across the city and internationally. Where core themes constructively overlap, we look to amplify such Director Keith Wilson in conversation with Harry Blain, Jacob Clary, Eileen Clancy, Christian Lewis, Dilara O’Neil, and artist crossover with bold public programming, as well as organize events that Mariam Ghani at screening of Dis-Ease, 2019. -

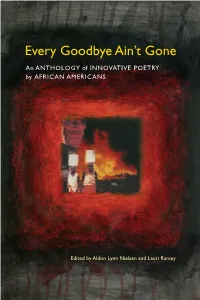

Every Goodbye Ain't Gone

Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone An ANTHOLOGY of INNOVATIVE POETRY by AFRICAN AMERICANS Edited by Aldon Lynn Nielsen and Lauri Ramey Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY POETICS Series Editors Charles Bernstein Hank Lazer Series Advisory Board Maria Damon Rachel Blau DuPlessis Alan Golding Susan Howe Nathaniel Mackey Jerome McGann Harryette Mullen Aldon Nielsen Marjorie Perloff Joan Retallack Ron Silliman Lorenzo Thomas Jerr y Ward You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone An Anthology of Innovative Poetry by African Americans Edited by ALDON LYNN NIELSEN and LAURI RAMEY THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA PRESS Tuscaloosa You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. Copyright © 2006 The University of Alabama Press Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35487-0380 All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Typeface: Janson Text ∞ The paper on which this book is printed meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

Addison Street Poetry Walk

THE ADDISON STREET ANTHOLOGY BERKELEY'S POETRY WALK EDITED BY ROBERT HASS AND JESSICA FISHER HEYDAY BOOKS BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA CONTENTS Acknowledgments xi Introduction I NORTH SIDE of ADDISON STREET, from SHATTUCK to MILVIA Untitled, Ohlone song 18 Untitled, Yana song 20 Untitied, anonymous Chinese immigrant 22 Copa de oro (The California Poppy), Ina Coolbrith 24 Triolet, Jack London 26 The Black Vulture, George Sterling 28 Carmel Point, Robinson Jeffers 30 Lovers, Witter Bynner 32 Drinking Alone with the Moon, Li Po, translated by Witter Bynner and Kiang Kang-hu 34 Time Out, Genevieve Taggard 36 Moment, Hildegarde Flanner 38 Andree Rexroth, Kenneth Rexroth 40 Summer, the Sacramento, Muriel Rukeyser 42 Reason, Josephine Miles 44 There Are Many Pathways to the Garden, Philip Lamantia 46 Winter Ploughing, William Everson 48 The Structure of Rime II, Robert Duncan 50 A Textbook of Poetry, 21, Jack Spicer 52 Cups #5, Robin Blaser 54 Pre-Teen Trot, Helen Adam , 56 A Strange New Cottage in Berkeley, Allen Ginsberg 58 The Plum Blossom Poem, Gary Snyder 60 Song, Michael McClure 62 Parachutes, My Love, Could Carry Us Higher, Barbara Guest 64 from Cold Mountain Poems, Han Shan, translated by Gary Snyder 66 Untitled, Larry Eigner 68 from Notebook, Denise Levertov 70 Untitied, Osip Mandelstam, translated by Robert Tracy 72 Dying In, Peter Dale Scott 74 The Night Piece, Thorn Gunn 76 from The Tempest, William Shakespeare 78 Prologue to Epicoene, Ben Jonson 80 from Our Town, Thornton Wilder 82 Epilogue to The Good Woman of Szechwan, Bertolt Brecht, translated by Eric Bentley 84 from For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide I When the Rainbow Is Enuf, Ntozake Shange 86 from Hydriotaphia, Tony Kushner 88 Spring Harvest of Snow Peas, Maxine Hong Kingston 90 Untitled, Sappho, translated by Jim Powell 92 The Child on the Shore, Ursula K. -

Hurlement: Une Traduction Du Poeme « Howl» Emilie Arseneault Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2012 Hurlement: une traduction du poeme « Howl» Emilie Arseneault Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Arseneault, Emilie, "Hurlement: une traduction du poeme « Howl»" (2012). Honors Theses. 764. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/764 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hurlement : une traduction du poème « Howl » Emilie Arseneault ********* Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Modern Languages Union College Winter, 2012 Hurlement – Traduction Français de Howl Emilie Arseneault Remerciements Je voudrais remercier Professeur Batson pour son aide avec cette traduction. Je voudrais aussi remercier mes parents pour leur support moral. Merci aussi à tous les professeurs qui m’ont aidé avec mon français pendant mon temps à Union. Je voudrais dédier cette thèse aux grands esprits à venir. 2 Hurlement – Traduction Français de Howl Emilie Arseneault Note de la traductrice : Introduction à « Howl » en français J’imagine que de nombreuses personnes pourraient se demander à quoi bon une traduction du poème « Howl » du célèbre poète américain Allen Ginsberg. Pour moi, la raison est évidente. Une traduction française de ce poème est pourrait contribuer à la richesse des lettres française, certes. Mais mon but principale est de faire reconnaître un des grands artiste qui a influencé de multiples mouvements et aux moins trois générations d’américain. -

Downbeat.Com December 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 . U.K DECEMBER 2014 DOWNBEAT.COM D O W N B E AT 79TH ANNUAL READERS POLL WINNERS | MIGUEL ZENÓN | CHICK COREA | PAT METHENY | DIANA KRALL DECEMBER 2014 DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Žaneta Čuntová Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Kevin R. Maher Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

The Impact of Allen Ginsberg's Howl on American Counterculture

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository UNIVERSITY OF RIJEKA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Vlatka Makovec The Impact of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl on American Counterculture Representatives: Bob Dylan and Patti Smith Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the M.A.in English Language and Literature and Italian language and literature at the University of Rijeka Supervisor: Sintija Čuljat, PhD Co-supervisor: Carlo Martinez, PhD Rijeka, July 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to explore the influence exerted by Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl on the poetics of Bob Dylan and Patti Smith. In particular, it will elaborate how some elements of Howl, be it the form or the theme, can be found in lyrics of Bob Dylan’s and Patti Smith’s songs. Along with Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and William Seward Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Ginsberg’s poem is considered as one of the seminal texts of the Beat generation. Their works exemplify the same traits, such as the rejection of the standard narrative values and materialism, explicit descriptions of the human condition, the pursuit of happiness and peace through the use of drugs, sexual liberation and the study of Eastern religions. All the aforementioned works were clearly ahead of their time which got them labeled as inappropriate. Moreover, after their publications, Naked Lunch and Howl had to stand trials because they were deemed obscene. Like most of the works written by the beat writers, with its descriptions Howl was pushing the boundaries of freedom of expression and paved the path to its successors who continued to explore the themes elaborated in Howl. -

Religion and Spirituality in the Work of the Beat Generation

DOCTORAL THESIS Irrational Doorways: Religion and Spirituality in the Work of the Beat Generation Reynolds, Loni Sophia Award date: 2011 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 Irrational Doorways: Religion and Spirituality in the Work of the Beat Generation by Loni Sophia Reynolds BA, MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of English and Creative Writing University of Roehampton 2011 Reynolds i ABSTRACT My thesis explores the role of religion and spirituality in the work of the Beat Generation, a mid-twentieth century American literary movement. I focus on four major Beat authors: William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Gregory Corso. Through a close reading of their work, I identify the major religious and spiritual attitudes that shape their texts. All four authors’ religious and spiritual beliefs form a challenge to the Modern Western worldview of rationality, embracing systems of belief which allow for experiences that cannot be empirically explained. -

Robert Glasper's In

’s ION T T R ESSION ER CLASS S T RO Wynton Marsalis Wayne Wallace Kirk Garrison TRANSCRIP MAS P Brass School » Orbert Davis’ Mission David Hazeltine BLINDFOLD TES » » T GLASPE R JAZZ WAKE-UP CALL JAZZ WAKE-UP ROBE SLAP £3.50 £3.50 U.K. T.COM A Wes Montgomery Christian McBride Wadada Leo Smith Wadada Montgomery Wes Christian McBride DOWNBE APRIL 2012 DOWNBEAT ROBERT GLASPER // WES MONTGOMERY // WADADA LEO SmITH // OrbERT DAVIS // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2012 APRIL 2012 VOLume 79 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed News Editor Hilary Brown Reviews Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editors Ed Enright Zach Phillips Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

Special Issue 4 April 2018 E-ISSN: 2456-5571

BODHI International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Science An Online, Peer reviewed, Refereed and Quarterly Journal Vol: 2 Special Issue: 4 April 2018 E-ISSN: 2456-5571 UGC approved Journal (J. No. 44274) CENTRE FOR RESOURCE, RESEARCH & PUBLICATION SERVICES (CRRPS) www.crrps.in | www.bodhijournals.com BODHI BODHI International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Science (ISSN: 2456-5571) is online, peer reviewed, Refereed and Quarterly Journal, which is powered & published by Center for Resource, Research and Publication Services, (CRRPS) India. It is committed to bring together academicians, research scholars and students from all over the world who work professionally to upgrade status of academic career and society by their ideas and aims to promote interdisciplinary studies in the fields of humanities, arts and science. The journal welcomes publications of quality papers on research in humanities, arts, science. agriculture, anthropology, education, geography, advertising, botany, business studies, chemistry, commerce, computer science, communication studies, criminology, cross cultural studies, demography, development studies, geography, library science, methodology, management studies, earth sciences, economics, bioscience, entrepreneurship, fisheries, history, information science & technology, law, life sciences, logistics and performing arts (music, theatre & dance), religious studies, visual arts, women studies, physics, fine art, microbiology, physical education, public administration, philosophy, political sciences, psychology, population studies, social science, sociology, social welfare, linguistics, literature and so on. Research should be at the core and must be instrumental in generating a major interface with the academic world. It must provide a new theoretical frame work that enable reassessment and refinement of current practices and thinking. This may result in a fundamental discovery and an extension of the knowledge acquired. -

20Questions Interview by David Brent Johnson Photography by Steve Raymer for David Baker

20questions Interview by David Brent Johnson Photography by Steve Raymer for David Baker If Benny Goodman was the “King of Swing” periodically to continue his studies over the B-Town and Edward Kennedy Ellington was “the Duke,” next decade, leading a renowned IU-based then David Baker could be called “the Dean big band while expanding his artistic and Hero and Jazz of Jazz.” Distinguished Professor of Music at compositional horizons with musical scholars Indiana University and conductor of the Smithso- such as George Russell and Gunther Schuller. nian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra, he is at home In 1966 he settled in the city for good and Legend performing in concert halls, traveling around the began what is now a world-renowned jazz world, or playing in late-night jazz bars. studies program at IU’s Jacobs School of Music. Born in Indianapolis in 1931, he grew up A pioneer of jazz education, a superlative in a thriving mid-20th-century local jazz scene trombonist forced in his early 30s to switch that begat greats such as J.J. Johnson and Wes to cello, a prolific composer, Pulitzer and Montgomery. Baker first came to Bloomington Grammy nominee and Emmy winner whose as a student in the fall of 1949, returning numerous other honors include the Kennedy 56 Bloom | August/September 2007 Toddler David in Indianapolis, circa 1933. Photo courtesy of the Baker family Center for the Performing Arts “Living Jazz Legend Award,” he performs periodically in Bloomington with his wife Lida and is unstintingly generous with the precious commodity of his time.