Planetary Cartography: What, How, and Why Begin with Where

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Cartography: the Development and Critique of Maps and Mapmaking

1. Cartography: the development and critique of maps and mapmaking Maps ‘are once again in the thick of it’ for critical social theorists, artists, literary critics and cultural geographers, but also in a very different way for planners, GIS researchers and scientists. Art and science offer different cartographic explanations. There are profound differences between those who research mapping as a practical form of applied knowledge, and those who seek to critique the map and the mapping process. (Perkins 2003: 341-342) Cartography is the study of maps and map-making. Classically, it focused on the art of the map-maker; today it includes the history of maps and their use in society. A map, as defined by the International Cartographic Association (2009), is ‘a symbolised image of geographical reality, representing selected features or characteristics, resulting from the creative effort of its author's execution of choices, and is designed for use when spatial relationships are of primary relevance’. While this definition eloquently indicates the varying constructions of maps, leading to the different ways maps are conceptualised and produced within society, its basic premise -- that a map is first and foremost ‘a symbolised image of a geographical reality’ -- has been challenged with the rise of a critical cartography/geography. Taking this definition as a starting premise, this chapter will seek to illustrate the ‘creativity’ and ‘selectivity’ of maps through a brief history of cartography, before embarking in later sections on a more critical analysis of the debates that surround the subject. The primary goal here is to understand the lessons that can be drawn from the historical development of cartography in a bid to assist contemporary criminologists in the development of more appropriate questions about maps and ultimately the process of crime mapping itself. -

The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century

The AAG Review of Books ISSN: (Print) 2325-548X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rrob20 The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century Jörn Seemann To cite this article: Jörn Seemann (2016) The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century, The AAG Review of Books, 4:3, 159-161, DOI: 10.1080/2325548X.2016.1187504 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/2325548X.2016.1187504 Published online: 07 Jul 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 312 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rrob20 The AAG Review OF BOOKS The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century Mark Monmonier, ed. Chicago, document how all cultures of all his- IL: University of Chicago Press, torical periods represented the world 2015. 1,960 pp., set of 2 using maps” (Woodward 2001, 28). volumes, 805 color plates, What started as a chat on a relaxed 119 halftones, 242 line drawings, walk by these two authors in Devon, England, in May 1977 developed into 61 tables. $500.00 cloth (ISBN a monumental historia cartographica, 978-0-226-53469-5). a cartographic counterpart of Hum- boldt’s Kosmos. The project has not Reviewed by Jörn Seemann, been finished yet, as the volumes on Department of Geography, Ball the eighteenth and nineteenth cen- State University, Muncie, IN. tury are still in preparation, and will probably need a few more years to be published. -

What Is Geovisualization? to the Growing Field of Geovisualization

This issue of GeoMatters is devoted What is Geovisualization? to the growing field of geovisualization. Brian McGregor uses geovisualiztion to by Joni Storie produce animated maps showing settle- ment patterns of Hutterite colonies. Dr. Marc Vachon’s students use it to produce From a cartography perspective, dynamic presentation options to com- videos about urban visualization (City geovisualization represents a change in municate knowledge. For example, at- Hall and Assiniboine Park), while Dr. how knowledge is formed and repre- lases require extra planning compared Chris Storie shows geovisualiztion for sented. Traditional cartography is usu- to individual maps, structurally they retail mapping in Winnipeg. Also in this issue Honours students describe their ally seen a visualization (a.k.a. map) could include hundreds of maps, and thesis projects for the upcoming collo- that is presented after the conclusion all the maps relate to each other. Dr. quium next March, Adrienne Ducharme is reached to emphasize or compliment Danny Blair and Dr. Ian Mauro, in the tells us about her graduate research at the research conclusions. Geovisual- Department of Geography, provide an ELA, we have a report about Cultivate ization changes this format by incor- excellent example of this integration UWinnipeg and our alumni profile fea- porating spatial data into the analysis with the Prairie Climate Atlas (http:// tures Michelle Méthot (Smith). (O’Sullivan and Unwin, 2010). Spatial www.climateatlas.ca/). The combina- Please feel free to pass this newsletter data, statistics and analysis are used to tion of maps with multimedia provides to anyone with an interest in geography. answer questions which contribute to for better understanding as well as en- Individuals can also see GeoMatters at the Geography website, or keep up with the conclusion that is reached within riched and informative experiences of us on Facebook (Department of Geog- the research. -

History of Cartography by Trista L

Name Date History of Cartography By Trista L. Pollard Our view of the world has changed since 1500 years ago. The maps and globes we use today are very accurate. They show more details. You can see cities and countries. They show landforms and landmarks. Our maps now have a standard coordinate or grid system. This measurement system helps us to locate places on Earth. But what about the first maps? What are they like? How were they made? Let's take a journey into the history of cartography. Cartography is the science of making maps. Today's cartographers use computers and cameras to help make maps. This is called remote sensing. Cameras are placed or mounted on airplanes. These cameras take pictures of the Earth's surface. Satellites in space are also used for cartography. Mapmakers in the past had much less technology. They used observation and stories from sailors to make maps. Most early scientists believed the Earth was flat. Imagine sailing from your country and falling over a cliff! That's what people thought. They also thought Earth was a flat disc. The center of the disc was filled with people. The outer edges of the Earth were empty. A world map made as early as 500 B.C. showed a disc with two continents. These continents were Europe and Asia. Both were surrounded by an ocean. That makes sense! Most people only knew about their surrounding or immediate area. Geographers also found early maps of the Pacific Ocean. They were made by navigators from Polynesia or the Pacific Islands. -

Leveraging Styles in Arcgis

Leveraging Styles in ArcGIS Pro Edie Punt Kenneth Field John Nelson Line symbols What’s in a style? Polygon symbols Point symbols Text symbols Label placements Colors N Color schemes North arrows Scale bars 0 1 2 km Why use styles? • Organize & reuse - Categories & tags • Match specifications - Colors, color models, line weights • Share - SQLite database stored as a single file - *.stylx file - File share or ArcGIS Online item Beer style Kenneth Field Styles are project items • They populate the galleries • System styles – installed with ArcGIS Pro • Custom styles – make your own or add from somewhere else • Favorites style – tied to your user account, always available • Top of galleries • Sandbox to experiment Manage styles in Catalog view • Add and import styles • Create and modify style items • Copy & paste items between styles • Manage tags and other metadata • Upgrade to current version Search for symbols in a gallery • Name, Category, and Tags all used as search terms • Use Category to rearrange galleries • Search Project styles or All styles Redlands Historical Map Kenneth Field Import ArcMap styles - .style file extension - Creates an ArcGIS Pro stylx version and adds it to the project - ArcMap styles in *.stylx format at https://esri-styles.maps.arcgis.com Styles on ArcGIS Online - ArcMap styles converted to the ArcGIS Pro *.stylx format and are accessible from https://esri-styles.maps.arcgis.com - PDF catalogs of many Esri styles are here Firefly style John Nelson Color - Save to Favorites to make accessible in galleries - Use -

CHAPTER 9 DATA DISPLAY and CARTOGRAPHY 9.1 Cartographic

CHAPTER 9 DATA DISPLAY AND CARTOGRAPHY 9.1 Cartographic Representation 9.1.1 Spatial Features and Map Symbols 9.1.2 Use of Color 9.1.3 Data Classification 9.1.4 Generalization Box 9.1 Representations 9.2 Types of Quantitative Maps Box 9.2 Locating Dots on a Dot Map Box 9.3 Mapping Derived and Absolute Values 9.3 Typography 9.3.1 Type Variations 9.3.2 Selection of Type Variations 9.3.3 Placement of Text in the Map Body Box 9.4 Options for Dynamic Labeling 9.4 Map Design 9.4.1 Layout Box 9.5 Wizards for Adding Map Elements 9.4.2 Visual Hierarchy 9.5 Map Production Box 9.6 Working with Soft-Copy Maps Box 9.7 A Web Tool for Making Color Maps Key Concepts and Terms Review Questions Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Applications: Data Display and Cartography Task 1: Make a Choropleth Map Task 2: Use Graduated Symbols, Line Symbols, Highway Shield Symbols, and Text Symbols Task 3: Label Streams Challenge Task References 1 Common Map Elements zCommon map elements are the title, body, legend, north arrow, scale, acknowledgment, and neatline/map border. zOther elements include the graticule or grid, name of map projection, inset or location map, and data quality information. Figure 9.1 Common map elements. 2 Cartographic Representation zCartography is the making and study of maps in all their aspects. zCartographers classify maps into general reference or thematic, and qualitative or quantitative. Spatial Features and Map Symbols zTo display a spatial feature on a map, we use a map symbol to indicate the feature’s location and a visual variable, or visual variables, with the symbol to show the feature’s attribute data. -

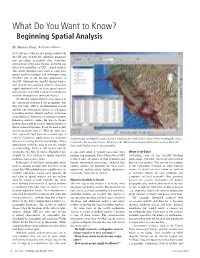

Beginning Spatial Analysis

What Do You Want to Know? Beginning Spatial Analysis By Monica Pratt, ArcUser Editor New GIS users who are just getting to know the ArcGIS suite of tools for capturing, managing, and presenting geospatial data sometimes overlook one of the most exciting, powerful, and distinctive capabilities of GIS—spatial analysis. This article introduces new users to some basic spatial analysis concepts and techniques using ArcMap, one of the desktop applications of ArcGIS. Although the ArcGIS Spatial Analyst and ArcGIS Geostatistical Analyst extensions supply additional tools, the basic spatial analysis functionality of ArcGIS is powerful and directly available through tools and menu choices. Simply put, spatial analysis encompasses all the operations performed on geographic data that add value. GIS is an information system, and like any information system, it is designed to produce answers. Spatial analysis can be used in an inductive, deductive, or normative manner. Inductive analysis studies the data to discern patterns that might be used to support theories or derive general principles. It can be used to help answer questions such as “Why do some areas have especially high rates of a certain type of cancer?” Deductive applications use geospatial Symbolizing earthquake events using a single point symbol does show where earthquakes have data to test existing theories or principles. These occurred—but not much more. However, the MAG (magnitude) fi eld can be used to fi lter the applications might be used to test the validity data and display it more meaningfully. of relationships between risk factors and the occurrence of a type of cancer. Normative uses is especially adept at visually perceiving both Where Is the Data? identify the best solution to spatial-dependent patterns and anomalies. -

Walch World History I Unit 1

WALCH WORLD HISTORY I UNIT 1 Walch – World History I Performance-Based Assessment Option for Unit 1 A performance-based assessment is one that requires students to demonstrate that they have mastered specific skills and competencies by performing or producing something. The Earliest People For the project you will be answering the following questions: • Why do you think the Nile River was crucial to the development of ancient Egyptian civilization? • Is the Fertile Crescent the same as Mesopotamia? Explain your answer. • Examine the geography of Mesopotamia. What does the geography suggest about why the city-states were constantly trying to conquer one another? Some Background Information Before Beginning the Project Cartography is the science or practice of drawing maps. It is the creation of charts and maps based on the layout of a territory's geography. Graphic design, also known as communication design, is the art and practice of planning and projecting ideas and experiences with visual and textual content. Infographics are graphic visual representations of information, data or knowledge intended to present information quickly and clearly. Visit the following site for some great examples of infographics. http://infographicworld.com/our- work/ The Project For this assessment, you will create an infographic. The infographic will be a map. Be creative. It can be hand-drawn or computer generated. Project Criterion The infographic should include the following: • Map the Fertile Crescent and Mesopotamia • Map of Ancient Egypt • Significant people, places, and events • Important information about people such as Sumerians, Babylonians. Assyrians, and Chaldeans, Persians, and Phoenicians • Answers to the above questions Assessment Tool: Bridgeway Academy Project Rubric: WALCH WORLD HISTORY I UNIT 1 . -

Exploratory Three Dimensional Cartographic Visualisation of Geolocated Datasets

Exploratory Three Dimensional Cartographic Visualisation of Geolocated Datasets A Thesis Submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Design Innovation Alexandre Bannwarth _ this thesis was completed as an online portfolio available at axbwh.thesis.surge.sh Victoria University of Wellington 2018 Figure 1. Thann Topographic Street Map. Abstract While digital technologies have vastly facilitated the generation and consumption of cartographic visualisations, the majority still conform to traditional two-dimensional map making guidelines. Consequently, design principles for three-dimensional cartographic models are still in their infancy and require further exploratory research to establish a comprehensive design framework. The free availability of high resolution global digital elevation models (GDEM), such as the ASTER GDEM (NASA LP DAAC, METI, 2011), makes it possible to develop accurate three-dimensional landscape visualisations and offer more intuitive and immersive representation of spatial information. Combined with the prevalence of geolocated content in both online data-repository and social-media platforms, there exists a wealth of material to be mined, interpreted and juxtaposed in exploratory cartographic visualisations. This thesis aims to establish a flexible and iterative procedural workflow to acquire, interpret and visualise 3D geolocated datasets, without compromising aesthetic control. Synergic with the procedural approach required for data collection and analysis, a procedural approach is used in the design of the visual output. This workflow aims to maximise automation and allow for the interpretation of a range of different data sources. The creative output of this process explores emergent cartographic principles for optimal three-dimensional spatial visualisation and investigate data presentation techniques beyond traditional two-dimensional geo-visualisation guidelines. -

Paradigmatic Tendencies in Cartography: a Synthesis of the Scientific-Empirical, Critical and Post-Representational Perspectives

Fakultät Forst-, Geo- und Hydrowissenschaften Paradigmatic Tendencies in Cartography: A Synthesis of the Scientific-Empirical, Critical and Post-Representational Perspectives Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) vorgelegt von M.Sc. Pablo Iván Azócar Fernández Gutachter: Herr Prof. Dr. phil.habil. Manfred F. Buchroithner Technische Universität Dresden Herr Prof. Dr. Zsolt G. Török Eötvös Lórand University, Budapest Dresden, February 09, 2012 Die Übereinstimmung dieses Exemplars mit dem Original der Dissertation zum Thema: „Paradigmatic Tendencies in Cartography: A Synthesis of the Scientific-Empirical, Critical and Post-Representational Perspectives“ wird hiermit bestätigt. ……………………………………….…. Ort, Datum Azócar, Pablo ……………………………………….…. Unterschrift (Vorname Name) i Abstract Maps have been important elements of visual representation in the development of different societies, and for this reason they have mainly been considered from a practical and utilitarian point of view. This means that cartographers or mapmakers have largely focused on the technical aspects of the cartographic products, and cartography has given little attention to both its theoretical component and to its philosophical and epistemological aspects. The current study is dedicated to consider these views. In this study the main trends, thoughts and different directions in cartography during positivism/empiricism, neo-positivism and post-structuralism are reviewed; and cartography is analysed under the modernism and post-modernism periods. Some of the arguments proposed by philosophers such as Ludwig Wittgenstein and Karl Popper are examined as important contributions in our understanding of the development of cartography and mapping. This study also incorporates the idea or concept of paradigm, which has been taken from the field of the epistemology of sciences. -

Mobile Mapping Mobile Mapping Mediamatters

media Mobile Mapping matters Space, Cartography and the Digital Amsterdam University clancy wilmott Press Mobile Mapping MediaMatters MediaMatters is an international book series published by Amsterdam University Press on current debates about media technology and its extended practices (cultural, social, political, spatial, aesthetic, artistic). The series focuses on critical analysis and theory, exploring the entanglements of materiality and performativity in ‘old’ and ‘new’ media and seeks contributions that engage with today’s (digital) media culture. For more information about the series see: www.aup.nl Mobile Mapping Space, Cartography and the Digital Clancy Wilmott Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by a grant from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Community’s 7th Framework program (FP7/2007-2013)/ ERC Grant Number: 283464 Cover illustration: Clancy Wilmott Cover design: Suzan Beijer Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 453 0 e-isbn 978 90 4853 521 7 doi 10.5117/9789462984530 nur 670 © C. Wilmott / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2020 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 7 Part 1 – Maps, Mappers, Mapping 1. -

GEOG 2104 – Introduction to Cartography &

GEOG 2104 – Introduction to Cartography & GIS (Cowan, Hinton, Johnson, Wiseman) The objective of this course is to gain an understanding of basic cartographic issues and GIS concepts, and their use in a specific GIS application (ArcGIS 10). This course is directed at students seeking to gain an initial introduction to GIS, including those intending to follow the GIS minor at GWU. This course is roughly fifty percent cartographic principles and fifty percent GIS fundamentals. Lab assignments will constitute forty percent of the overall grade and are designed to provide the student with a basic software overview and introductory competency. Prerequisites: There are no prerequisites for this course, but it is suggested that you take Geog 2105 – Techniques of Spatial Analysis, in tandem with Geog 2104, if you intend to pursue further advanced GIS classes GEOG 2105 – Techniques of Spatial Analysis (Streletskiy, Hurley) The primary objective of this course is to familiarize you with basic concepts and methods used in spatial analysis, a field which spans many related disciplines and which brings together many tools for describing and analyzing spatial data. We will learn how to analyze and interpret geographical data, when to use a certain procedure, and how to apply statistics in your own work. The course will begin by reviewing statistical concepts and techniques used in traditional aspatial analysis. You will develop an understanding of some of the limitations associated with spatial data when applying traditional statistical approaches, as well as the challenge of selecting analytical techniques when data are known to be spatially autocorrelated. Techniques and methods that have been designed to handle spatial data will be taught, and include point- pattern analysis and measures of spatial autocorrelation.