2, Imported Cosmetics and Colonial Crucibles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People's Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University Abd El Hamid Ibn Badis Faculty of Foreign Languages Department of English Master in Literature and Interdisciplinary Approaches The US Beauty Industry and the Other Face of Racism towards the 21st Century African -American Women Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master in Literature and Interdisciplinary Approaches Submitted By: Reguig Khadidja Board of Examiners: Chairperson: Ms. Bellel Hanane Supervisor: Mr. Teguia Cherif Examiner: Mrs. Adnani Rajaa 2018-2019 Dedication It is my genuine gratefulness and warmest regard that I dedicate this work to my beloved people who have meant and continue to mean so much to me. Although some of them are no longer in this world, their memories will always stay engraved in my heart. First and foremost, to my dear late grandmother Fatma who taught me kindness. To my family: my parents, my brothers and sisters for believing in me and for their unceasing encouragements and support. I would like to dedicate my work to my friends from secondary school days: Sarra and Omar. Unfortunately, I cannot mention everyone by name, it would take a lifetime. Just make sure you all count so much to me. Without your prayers, benedictions, sincere love and help, I would have never completed this dissertation. i Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Mr. Teguia Cherif for his continuous support, patience, motivation, and immense knowledge. His guidance helped me all the time of research and writing of this dissertation. -

Lead Poisoning from the Colonial Period to the Present

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1996 Lead Poisoning from the Colonial Period to the Present Elsie Irene Eubanks College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Eubanks, Elsie Irene, "Lead Poisoning from the Colonial Period to the Present" (1996). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626037. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-3p5y-hz98 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEAD POISONING FROM THE COLONIAL PERIOD TO THE PRESENT A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology The College of William and Mary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Elsie Irene Eubanks 1996 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, May 1996 <yf/f ' Norman Barka Marley Brown J Theodore Reinhart TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER I. ARCHAEOLOGY AND HUMAN LEAD BONE CONTENT ............................................................................ 8 CHAPTER II. A STUDY OF HISTORIC LEAD GLAZED CERAMICS ......................................................................... 16 CHAPTER III. JOSIAH WEDGWOOD - A STUDY OF LEAD AND THE P O T T E R ................................................................... -

2020-21 Course Descriptions

2020-21 Course Descriptions Students should consult their success adviser and faculty adviser each quarter prior to registering for courses to be sure they are meeting graduation requirements for their course of study and taking appropriate electives. ACCESSORY DESIGN UNDERGRADUATE ACCE 101 Accessory Design Immersion Students discover the world of fashion accessory design with an in-depth exploration of the evolution of accessory trends, brands and research methodologies. Students learn to sketch accessory concepts, make patterns and select finishing techniques to bring accessory ideas to fruition. Through operating sewing machines, cutting tables and skiving machines students learn how to craft accessories with skill and precision. Prerequisite(s): DRAW 100, DSGN 102, any major or minor except accessory design. ACCE 110 Sewing Technology for Accessory Design This course introduces students to the industry practices involved in producing accessories. Students also are introduced to decorative ornamentation techniques while applying these techniques to accessory design. Basic patternmaking skills are taught and provide the foundation for future courses in accessory design. Prerequisite(s): None. ACCE 120 Materials and Processes for Accessory Design This course introduces students to core materials used in the implementation of accessory design products. By exploring the qualities and properties of traditional materials, students learn the basics of traditional and nontraditional materials. Students explore a variety of techniques related to accessory design with leather, from tanning to production. This course also explores alternative materials used in accessory products such as rubber, synthetics, woods and metals, as well as cements. This course requires experimentation culminating in a final project which explores individualized processes and material manipulation. -

Geocaching Warning

12 04 09 | reportermag.com Geocaching Using multi-million-dollar satellites to find tupperware in the woods. Warning: Unwanted Knowledge The surprising ingredients in personal care products. WITR Mired in Controversy Student radio under fire from alumni and community members. TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 04 09 | VOLUME 59 | ISSUE 11 A Rock Band 2 competitor rocks out during the October 24 tournament. Photograph by Shinay McNeill. NEWS PG. 06 SPORTS PG. 22 SG Update Interveiw With Adam Frank Winter Sports Preview Destler to deliver verdict on semesters in Reporter sits down with the author of “The The snow’s falling and winter sports are taking spring. Constant Fire.” the field. Staff Council Reviews Of the 14,000 ordered, RIT only recieves 300 Why John Mayer’s 4th album might not be VIEWS PG. 27 H1N1 vaccines. worth a listen. Artifacts RIT/ROC Forecast At Your Leisure Remember Windows 95? Holiday Songs and Skies Planetarium Show is Reporter recommends: Sporcle. The dude Grandpa’s Garbage Plate the new hot date spot. abides. One man’s trash... WITR Mired in Controversy RIT Rings Student radio leadership under fire from FEATURES PG. 16 Seriously, why does Lady Gaga have a [disco alumni and community members. Geocaching stick]? Using multi-million-dollar satellites to find LEISURE PG. 10 tupperware in the woods. Warning: This Product May Contain Unwanted Alternate Reality Gaming Knowledge Fiction never felt so real. The suprising ingredients in personal care products. Cover illiustration by Jamie Douglas EDITOR IN CHIEF Andy Rees EDITOR’S NOTE | [email protected] MANAGING EDITOR Madeleine Villavicencio | [email protected] THE MORE THINGS CHANGE COPY EDITOR Michael Conti When I was in high school, I took a lot of history courses. -

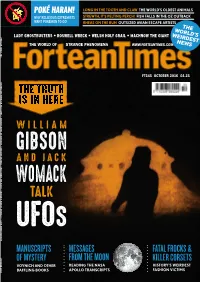

Womack and Gibson the Truth Is in Here

POKÉ HARAM! LONG IN THE TOOTH AND CLAW THE WORLD'S OLDEST ANIMALS WHY RELIGIOUS EXTREMISTS STREWTH, IT'S PELTING PERCH! FISH FALLS IN THE OZ OUTBACK WANT POKÉMON TO GO! RHEAS ON THE RUN OUTSIZED AVIAN ESCAPE ARTISTS THE WOR THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA LD’S LADY GHOSTBUSTERS • ROSWELL WRECK • WELSH HOLY GRAIL • MACHNOWWWW.FORTEANTIMES.COM THE GIANT WEIRDES FORTEAN TIMES 345 NEWS T THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA WWW.FORTEANTIMES.COM FT345 OCTOBER 2016 £4.25 GIBSON AND WOMACK TALK UFOS • MANUSCRIPTS OF MYSTERY • THE TRUTH IS IN HERE WILLIAM FA GIBSON SHION VICTIMS • MACHNOW THE GIANT • WORLD'S OLDEST ANIMALS • LADY GHOSTBUSTERS AND JACK WOMACK TALK UFOS MANUSCRIPTS MESSAGES FATALFROCKS& OCTOBER 2016 OFMYSTERY FROMTHEMOON KILLERCORSETS VOYNICH AND OTHER READING THE NASA HISTORY'S WEIRDEST BAFFLING BOOKS APOLLO TRANSCRIPTS FASHION VICTIMS LISTEN IT JUST MIGHT CHANGE YOUR LIFE LIVE | CATCH UP | ON DEMAND Fortean Times 345 strange days Pokémon versus religion, world’s oldest creatures, fate of Flight MH370, rheas on the run, Bedfordshire big cat, female ghostbusters, Australian fi sh fall, Apollo transcripts, avian CONTENTS drones, pornographer’s papyrus – and much more. 05 THE CONSPIRASPHERE 23 MYTHCONCEPTIONS 14 ARCHAEOLOGY 25 ALIEN ZOO the world of strange phenomena 15 CLASSICAL CORNER 28 NECROLOG 16 SCIENCE 29 FAIRIES & FORTEANA 18 GHOSTWATCH 30 THE UFO FILES features COVER STORY 32 FROM OUTER SPACE TO YOU JACK WOMACK has been assembling his collection of UFO-related books for half a century, gradually building up a visual and cultural history of the saucer age. Fellow writer and fortean WILLIAM GIBSON joined him to celebrate a shared obsession with pulp ufology, printed forteana and the search for an all too human truth.. -

Face Paint : the Story of Makeup

Editor: David Cashion Designers: Robin Derrick with Danielle Young Production Manager: True Sims Library of Congress Control Number: 2014959338 ISBN: 978-1-4197-1796-3 Text copyright © 2015 Lisa Eldridge See this page for photo credits. Published in 2015 by Abrams Image, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. Abrams Image books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact [email protected] or the address below. 115 West 18th Street New York, NY 10011 www.abramsbooks.com To my mother, whose makeup got me into all of this in the first place Contents Introduction Prologue: The Painted Face Section One The Ancient Palette Red: Beauty’s Most Enduring Shade White: The Politics and Power of Pale Black: Beauty’s Dark Mark Section Two The Business of Beauty Media and Motivation: Creating the Dream The Beauty Pioneers: Visionaries and Vaudeville History in Your Handbag: Folk Remedies to Global Brands The Bleeding Edge: Into the Future Afterword: I Want to Look Like You Acknowledgments Endnotes Photo Credits Index of Searchable Terms About the Author We’ve been altering our skin with paints and oils and dabbling in artistry since the Ice Age. A Introduction Although we have been painting ourselves in a variety of ways for thousands of years, the reasons why—and how—we wear makeup in the twenty-first century have changed dramatically. -

The Beautiful; Decorative 1992 Medieval Calendar!

Looking for the perfect gift for a history buff? Student? Teacher? Ricardian or S.C.A. member? It's here! (The beautiful; decorative 1992 Medieval Calendar! Richard Ill Society, Inc. Volume XV No. 3 Fall, 1991 All new hand-rendered art, an exciting new theme (Clothing Styles of the Middle Ages), a record of historical events, and membership information about the Richard III Society. Keep one for yourself and order several for gifts, promotions or public relations! If you have seen our calendars of past years, you already know that this is more than just an ordinary calendar-- it is an unusual work of art, a teaching tool, and a special way to introduce others to the Ricardian cause! Printed in russett on fine quality gold -colored parchment and vellum, the 1992 calendar depicts men and women garbed in various clothing styles from all walks of life, appropriate information and quotations pertaining to each. Art work, research and production by Richard III Society chapter members from Southern California. Proceeds will be used to benefit worthy Society causes and/or the Schallek memorial scholarship fund (for medieval studies). ORDER YOURS NOW — DON'T MISS OUT! Price per calendar, is ONLY $7.50 If ordered in quantities of ten or more shipped to the same address, a special 'wholesale' price of ONLY $5.00 per calendar will be extended. (Please add $1.00 ea. for postage, packaging and handling.) Local chapters and branches are encouraged to order in quantity and re-sell at the mark-up, if you wish, as a fund-raiser for your own treasury. -

Heavy Metal and the Beauty I

ACADEMIA Letters Heavy metal and the beauty industry: an unexpected connection from ancient Afghanistan St John Simpson There is a very long history of use of cosmetic in the Middle East [1]. In Iraq, excavated graves dating to the third millennium BC have been found to contain individual shells holding spe- cific colours: black/dark brown, blue, green, purple, red, yellow or white. Scientific analyses of those found at Ur indicate that the black/dark brown was usually manganese (pyrolusite), whereas the white was usually calcined bone but sometimes a lead-rich mineral (cerussite, laurionite and gypsum), whereas lead sulphide (galena) has so far only been found in a pair of cosmetic shells from Kish; the other colours were sourced from azurite (blue), oxidised cop- per minerals, notably atacamite and paratacamite (green), and ochre (red, yellow and purple) [2]. Although not previously described, it is clear from the appearance of the cake that they must have been mixed with a considerable amount of binder which has since evaporated and caused the pigment to contract, rather like shoe-polish in a poorly lidded container. More- over, impressions of a pointed applicator on some examples from Ur indicate that they had been used immediately prior to burial and the pigment most likely applied as eye-liner; on others there are impressions of woven textile, possibly from a small purse used to contain the shell and keep it moist. Isotopic analyses suggest that south-east Arabia was the source of the green, blue and black/dark brown pigments, and it is telling that the tradition of placing black (manganese mineral pyrolusite (MnO2)) or green (atacamite) cosmetic within shell containers is attested from that region from the late third millennium BC onwards [3]. -

Evaluation of Letsoku and Related Indigenous Clayey Soils

EVALUATION OF LETSOKU AND RELATED INDIGENOUS CLAYEY SOILS by Refilwe Morekhure-Mphahlele 96276313 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chemical Technology In the Faculty of Engineering, Built Environment and Information Technology University of Pretoria Pretoria Supervisor: Prof. WW Focke November 2017 DECLARATION I, Refilwe Morekhure-Mphahlele, the undersigned, declare that the thesis that I hereby submit for the degree PhD in Chemical Technology at the University of Pretoria is my original work. Acknowledgement has been given and reference made in instances where literature resources were used. The work has not been previously submitted by anyone for a degree or any examination at this or any other academic institution. __________________ _________________ Signature Place __________________ Date ii ABSTRACT The nature of letsoku and related clayey soils, traditionally used by indigenous Southern African communities for a wide range of purposes, was explored. Thirty-nine samples were collected from Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland, South Africa and Zimbabwe. They were analysed to determine their composition and physical properties. Structured interviews were used to establish the purpose of use and the location of sourcing sites. The samples were in the form of either powder or rocks, and some were supplied as dry rolled clay balls. Cosmetic applications were almost universally indicated. However, other functions, related to artwork, medicinal use, cultural symbolism and traditional beliefs, were also mentioned. The samples covered a wide range of colours from bright red to yellow, but also from off-white to black, with some having a light grey colour. It was therefore not surprising that the mineral composition of the letsoku samples also varied widely. -

The New York Environmental Lawyer a Publication of the Environmental & Energy Law Section of the New York State Bar Association

NYSBA 2020 | VOL. 40 | NO. 1 The New York Environmental Lawyer A publication of the Environmental & Energy Law Section of the New York State Bar Association Inside n Expert Advocacy in the Legal Setting n Omnipresent Chemicals: TSCA Preemption in the Wake of PFAS Contamination n A Special Harm That Affects Everyone: How One Can Use Climate Change to Obtain Standing Under SEQR NYSBA.ORG/ENVIRONMENTAL Section Officers THE NEW YORK Chair Nicholas M. Ward-Willis ENVIRONMENTAL LAWYER Keane & Beane, PC Editor-in-Chief 445 Hamilton Ave, Ste 1500 Miriam E. Villani White Plains, NY 10601 Sahn Ward, PLLC [email protected] 333 Earle Ovington Blvd, Ste 601 Uniondale, NY 11553 Vice-Chair [email protected] Linda R. Shaw Knauf Shaw LLP Issue Editors 2 State St, Ste 1400 Alicia G. Artessa Rochester, NY 14614 Government Relations Associate [email protected] Retail Council of New York State 258 State St Treasurer Albany, NY 12210 James P. Rigano [email protected] Rigano, LLC 538 Broadhollow Rd, Ste 217 Prof. Keith Hirokawa Melville, NY 11747 Albany Law School [email protected] 80 New Scotland Ave Albany, NY 12208 Secretary [email protected] Yvonne E. Hennessey Barclay Damon LLP Aaron Gershonowitz 80 State St Forchelli Curto Albany, NY 12207 333 Earle Ovington Blvd [email protected] Uniondale, NY 11553 [email protected] Publication—Editorial Policy—Subscriptions Law Student Editorial Board Persons interested in writing for this Journal are wel comed and Albany Law School and St. John’s University School of Law encouraged to submit their articles for con sid er ation. -

A Study of the Labels of Women's Foundations Jennie Selén

“Because you’re worth it” A Study of the Labels of Women’s Foundations Jennie Selén, 38555 Pro gradu -avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Brita Wårvik Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCOLOGY AND TEOLOGY Master’s thesis abstract Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Jennie Selén Title: “Because you’re worth it”: A Study of the Labels of Women’s Foundations Supervisor: Brita Wårvik Makeup has been around since ancient times; it is something which has been used by Cleopatra and Elizabeth I and is today used by millions of people around the world. It appears as if there has always been a desire to alter one’s skin tone. Trends have shifted from a preference for a lighter skin to the current trend of using self-tanning products to achieve a sun-kissed look. Today the selection of makeup products is very large. However, attention has been drawn to problems with the availability of different makeup products not to mention the labels these products have in particular for women with a darker skin colour. This thesis examines the labels which cosmetic companies give their foundations. The aim is to study what kinds of labels are used for different shades of foundations. The study is carried out by conducting a semantic categorisation in which the connotations of the most frequently used labels are examined. The interest is to see if there are any emerging patterns and differences for the labels given to the products depending on the skin colour of the person the product is aimed for. -

Queen Elizabeth's Makeup – a Frightening History in Beauty

Queen Elizabeth’s makeup – A Frightening History in beauty the face, neck and chest. Because lead is poison, smearing it all over one’s skin caused some serious skin damage. Not only did it make the skin look “grey and shriveled” there was lead poisoning, hair loss and if used over an extended period of time could cause death. Another way to get pale skin was to attach leeches to both cheeks which would suck blood out of the face. They lined their eyes with black kohl to make them look darker and used belladonna (also a poison) eye drops to dilate women’s pupils (dilated pupils were very romantic). Fashion required eyebrows to be thin and The cosmetics (makeup) that were worn by arched. a high forehead it was also considered women in the time of Queen Elizabeth were to be a sign of beauty and nobility. Women drastically different from those we wear today. would pluck out the hair from their eyebrows Not only were the materials they used very and forehead to achieve these looks. different but the look they were trying to Red Cheeks and red lips were very popular. achieve was very different as well. What is This was obtained with plants, beetle shell and considered “beautiful” changes all the time, animal dyes and then mixed with beeswax. depending on what period of time you are looking at. Queen Elizabeth had a great If women could not achieve the desired color of influence over what was considered “beautiful” light hair, they would wear wigs. Some women during her reign.