The Legal Implications of China's Accession to the WTO* Pitman B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Prominences1

THE THREE PROMINENCES1 Yizhong Gu The political-aesthetic principle of the “three prominences” (san tuchu 三突出) was the formula foremost in governing proletarian literature and art during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) (hereafter CR). In May 1968, Yu Huiyong 于会泳 initially proposed and defined the principle in this way: Among all characters, give prominence to the positive characters; among the positive characters, give prominence to the main heroic characters; among the main characters, give prominence to the most important character, namely, the central character.2 As the main composer of the Revolutionary Model Plays, Yu Hui- yong had gone through a number of ups and downs in the official hierarchy before finally receiving favor from Jiang Qing 江青, wife of Mao Zedong. Yu collected plenty of Jiang Qing’s concrete but scat- tered directions on the Model Plays and tried to summarize them in an abstract and formulaic pronouncement. The principle of three prominances was supposed to be applicable to all the Model Plays and thus give guidance for the creation of future proletarian artworks. Summarizing the gist of Jiang’s instruction, Yu observed, “Comrade Jiang Qing lays strong emphasis on the characterization of heroic fig- ures,” and therefore, “according to Comrade Jiang Qing’s directions, we generalize the ‘three prominences’ as an important principle upon which to build and characterize figures.”3 1 This essay owes much to invaluable encouragement and instruction from Profes- sors Ban Wang of Stanford University, Tani Barlow of Rice University, and Yomi Braester of the University of Washington. 2 Yu Huiyong, “Rang wenyi wutai yongyuan chengwei xuanchuan maozedong sixiang de zhendi” (Let the stage of art be the everlasting front to propagate the thought of Mao Zedong), Wenhui Bao (Wenhui daily) (May 23, 1968). -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript Pas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissenation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from anytype of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material bad to beremoved, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with smalloverlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell &Howell Information Company 300North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521·0600 THE LIN BIAO INCIDENT: A STUDY OF EXTRA-INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS IN THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AUGUST 1995 By Qiu Jin Dissertation Committee: Stephen Uhalley, Jr., Chairperson Harry Lamley Sharon Minichiello John Stephan Roger Ames UMI Number: 9604163 OMI Microform 9604163 Copyright 1995, by OMI Company. -

Download the Full Issue

East Asian History NUMBER 41 • AUGUST 2017 www.eastasianhistory.org CONTENTS 1–2 Guest Editor’s Preface Shih-Wen Sue Chen 3–14 ‘Aspiring to Enlightenment’: Buddhism and Atheism in 1980s China Scott Pacey 15–24 Activist Practitioners in the Qigong Boom of the 1980s Utiraruto Otehode and Benjamin Penny 25–40 Displaced Fantasy: Pulp Science Fiction in the Early Reform Era of the People’s Republic Of China Rui Kunze 王瑞 41–48 The Emergence of Independent Minds in the 1980s Liu Qing 刘擎 49–56 1984: What’s Been Lost and What’s Been Gained Sang Ye 桑晔 57–71 Intellectual Men and Women in the 1980s Fiction of Huang Beijia 黄蓓佳 Li Meng 李萌 online Chinese Magazines of the 1980s: An Online Exhibition only Curated by Shih-Wen Sue Chen Editor Benjamin Penny, The Australian National University Guest Editor Shih-Wen Sue Chen, Deakin University Editorial Assistant Lindy Allen Editorial Board Geremie R. Barmé (Founding Editor) Katarzyna Cwiertka (Leiden) Roald Maliangkay (ANU) Ivo Smits (Leiden) Tessa Morris-Suzuki (ANU) Design and production Lindy Allen and Katie Hayne Print PDFs based on an original design by Maureen MacKenzie-Taylor This is the forty-first issue of East Asian History, the fourth published in electronic form, August 2017. It continues the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. Contributions to www.eastasianhistory.org/contribute Back issues www.eastasianhistory.org/archive To cite this journal, use page numbers from PDF versions ISSN (electronic) 1839-9010 Copyright notice Copyright for the intellectual content of each paper is retained by its author. -

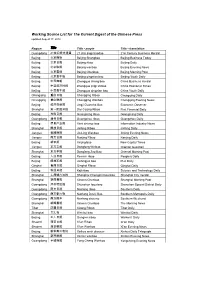

Working Source List for the Current Digest of the Chinese Press Updated August 17, 2012

Working Source List for The Current Digest of the Chinese Press updated August 17, 2012 Region Title Title - pinyin Title - translation Guangdong 21世纪经济报道 21 shiji jingji baodao 21st Century Business Herald Beijing 北京商报 Beijing Shangbao Beijing Business Today Beijing 北京日报 Beijing ribao Beijing Daily Beijing 北京晚报 Beijing wanbao Beijing Evening News Beijing 北京晨报 Beijing Chenbao Beijing Morning Post Beijing 北京青年报 Beijing qingnian bao Beijing Youth Daily Beijing 中国商報 Zhongguo shang bao China Business Herald Beijing 中国经济时报 Zhongguo jingji shibao China Economic Times Beijing 中国青年报 Zhongguo qingnian bao China Youth Daily Chongqing 重庆日报 Chongqing Ribao Chongqing Daily Chongqing 重庆晚报 Chongqing Wanbao Chongqing Evening News Beijing 经济观察报 Jingji Guancha Bao Economic Observer Shanghai 第一财经日报 Diyi Caijing Ribao First Financial Daily Beijing 光明日报 Guangming ribao Guangming Daily Guangdong 廣州日報 Guangzhou ribao Guangzhou Daily Beijing 信息产业报 Xinxi chanye bao Information Industry News Shanghai 解放日报 Jiefang Ribao Jiefang Daily Jiangsu 金陵晚报 Jin Ling Wanbao Jinling Evening News Jiangsu 南京日报 Nanjing Ribao Nanjing Daily Beijing 新京报 Xinjing bao New Capital Times Jiangsu 东方卫报 Dongfang Weibao Oriental Guardian Shanghai 东方早报 Dongfang Zao Bao Oriental Morning Post Beijing 人民日报 Renmin ribao People's Daily Beijing 解放军报 Jiefangjun bao PLA Daily Qinghai 青海日报 Qinghai Ribao Qinghai Daily Beijing 科技日报 Keji ribao Science and Technology Daily Shanghai 上海城市导报 Shanghai Chengshi Dao Bao Shanghai City Herald Shanghai 新闻晨报 Xinwen Chenbao Shanghai Morning Post Guangdong 深圳特区报 Shenzhen -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Academic nationalism Sleeboom, M.E. Publication date 2001 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Sleeboom, M. E. (2001). Academic nationalism. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 BIBLIOGRAPHY: European Languages Journals and translation services: Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs Current Anthropology CA China Quarterly CQ Chinese Sociology and Anthropology Discourse & Society FBIS Foreign Broadcast Information Service Foreign Affairs Issues & Studies l&S JPRS CPS Joint Publications Research Service: Chinese Politics and Society JPRS CST Joint Publications Research Service: Chinese Science and Technology Journal of Asian Studies Monumenta Nipponica The New Courant Peking Review SELMM Selected Materials from the Mainland (China) Social Science in China Strategy and Management S&M Volkskrant Altheide, D.L. -

Summary of a Talk with the Representatives of Press and Publishing Circles

T E X T E I G H T Summary of a Talk with the Representatives of Press and Publishing Circles 10 MARCH 1957 [75] From 3:00 to 7:00 P.M. on 10 March, Chairman Mao held an informal discussion in his office with representatives of the press and publishing circles. Participating in this informal discussion were Jin Zhonghua,1 the representative of Shanghai's Xinwen ribao [Daily Sources: 9:75-90, alternate text, 7:46-59. A truncated version of this exchange has been pub lished in Mao Zedong xinwen gongzuo wenxuan (A selection of Mao Zedong's writings on news work) (Beijing, Xinhua chubanshe, 1983), pp. 186-95. The excisions made in the 1983 version seem designed to gloss over contemporary political problems. An even briefer ver sion of this text appears in the restricted circulation publication, Wenxian he yanjiu: 1983 huibianben (Documents and research: 1983 Selections) (Beijing, Renmin chubanshe, 1984), pp. 54-62. That this last neibu version is less complete than the public version serves as a warning that "restricted circulation'' does not guarantee greater completeness. 1Jin Zhonghua (b. 1902) was one of China's leading journalists. He had worked in the 1930s 250 TEXT EIGHT News] and China News Service; Wang Yunsheng, representative [of] Dagong bao,Z [and] Shanghai [76] Wenhui baa's representative, Xu Zhucheng.3 To start the discussion, the Chairman first invited the non-party personages from Shanghai to speak. The Chairman asked when Shanghai's Shen bao was abolished. [When he] heard the reply that Shen bao stopped publishing after Liberation, the Chairman remarked: There was no reason to abolish Shen bao, so old a paper of several decades' standing. -

The Workers' Movement in China, 2005-2006

CLB Research Reports No.5 Speaking Out The Workers’ Movement in China (2005-2006) www.clb.org.hk December 2007 Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1: The economic, legislative and social background to the workers’ movement ............ 5 The economy........................................................................................................................... 5 Legislation and government policy......................................................................................... 6 Social change .......................................................................................................................... 9 Chapter 2. Worker Protests in 2005-06......................................................................................... 13 1. Privatization Disputes ....................................................................................................... 13 Worker protests during the restructuring of SOEs........................................................ 14 Worker protests after SOE restructuring....................................................................... 17 2. General Labour Disputes .................................................................................................. 20 Chapter 3. An Analysis of Worker Protests.................................................................................. 25 Chapter 4. Government Policies in Response to Worker Protests -

CHINESE COMMUNISM and the RISE of a CLASSIFICATION EDDY U Luminos Is the Open Access Monograph Publishing Program from UC Press

CREATING the INTELLECTUAL CHINESE COMMUNISM AND THE RISE OF A CLASSIFICATION EDDY U Luminos is the Open Access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Creating the Intellectual The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Sue Tsao Endowment Fund in Chinese Studies. Creating the Intellectual Chinese Communism and the Rise of a Classification Eddy U UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2019 by Eddy U This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses. Suggested citation: U, E. Creating the Intellectual: Chinese Communism and the Rise of a Classification. Oakland: University of California Press, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/luminos.68 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: U, Eddy, author. Title: Creating the intellectual : Chinese communism and the rise of a classification / Eddy U. -

UPDATE on ARRESTS in CHINA No.21

February 18, 1991 1 UPDATE ON ARRESTS IN CHINA No.2 INTRODUCTION Beginning in January 1990, Chinese officials began releasing dissidents arrested in connection with the spring 1989 pro-democracy movement, but the repression is by no means over. Arrests, trials and sentencings continue, and Chinese authorities still refuse to issue a list of those detained, arrested, tried or released. Only a handful of released activists - most of them internationally known - have been officially identified. Of the thousands arrested since June 1989, fewer than 1000 have been publicly identified, and few of those identifications come from official sources. Asia Watch has only recently become aware of certain arrests that may have taken place as long ago as June 1989. In many cases, the first indication that an arrest had occurred was official acknowledgment of trial and sentencing. Two dissidents, awaiting sentencing in Beijing for allegedly heading a counterrevolutionary group were previously unknown to human rights organizations and even now little information about their backgrounds or activities during the 1989 pro-democracy movement is available. Presumably they are workers who have had little opportunity to make their arrests known outside China. In another instance, at least two dissidents released in Beijing on January 26, 1991 were never officially listed as in detention. All this suggests that the true figure for the total arrested after June 4 may be much higher than earlier estimates. SUMMARY: 111 The current series of updates began with Update No.1, January 30, 1991. The updates should be read in conjunction with two 1990 Asia Watch reports, Punishment Season and Repression in China Since June 4, 1989: Cumulative Data and with a shorter report, "Rough Justice in Beijing," issued in January 1991. -

Dissertation (Fan Liao)

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Paradoxical Peking Opera: Performing Tradition, History, and Politics in 1949-1967 China A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Drama and Theatre by Fan Liao Committee in charge: University of California, San Diego Professor Janet L. Smarr, Chair Professor Paul G. Pickowicz, Co-Chair Professor Nancy A. Guy Professor Marianne McDonald Professor John S. Rouse University of California, Irvine Professor Stephen Barker 2012 The Dissertation of Fan Liao is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Chair University of California, San Diego University of California, Irvine 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………………iii Table of Contents……………………………………………………………....................iv Vita………………………………………………………………………………………...v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………...vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter One………………………………………….......................................................29 Reform of Jingju Old Repertoire in the 1950s Chapter Two……………………………………………………………………………...81 Making History: The Creation of New Jingju Historical Plays Chapter Three…………………………………………………………………………...135 Inventing Traditions: The Creation of New Jingju Plays with Contemporary Themes Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………...204 Appendix……………………………………………………………………………….211 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………229 iv VITA 2003 -

Student Activism and Campus Politics in China, 1957

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Blooming, Contending, and Staying Silent: Student Activism and Campus Politics in China, 1957 DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History by Yidi Wu Dissertation Committee: Professor Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Chair Professor Susan Morrissey Professor Paul Pickowicz 2017 © 2017 Yidi Wu DEDICATION To All my interviewees, who kindly shared their time, experience and wisdom with me. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION vi CHAPTER 1: Introduction: Student Activism in 1957’s China 1 CHAPTER 2: 1919, 1957, 1966, and 1989: Student Activism in Twentieth-Century China 14 CHAPTER 3: From Moscow to Beijing: Chinese Students Learn from Crises in the Soviet Bloc 39 CHAPTER 4: Student Activism as Contentious Politics at Peking University I: Contentious Repertoire and Framing Techniques 78 CHAPTER 5: Student Activism as Contentious Politics at Peking University II: Political Opportunity and Constraint, Organization and Mobilization, and Divisions 131 CHAPTER 6: Variations across Campuses: Similarities and Differences in Beijing, Wuhan and Kunming 168 CHAPTER 7: Stand in Line: Classification of College Students’ Political Reliability in the Anti-Rightist Campaign 205 CHAPTER 8: Epilogue: The Past Has Not Passed 257 REFERENCES 269 APPENDIX: Interview List 274 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express sincere gratitude to my dissertation committee. I could not ask for a better advisor, as Professor Wasserstrom has continued to help me connect with various people in the field, and he has provided opportunities for co-authorship in several publications. Professor Pickowicz generously included me in the UC San Diego Chinese history research seminar and the joint conference at East China Normal University, Shanghai. -

Zhang Jishun 张济顺, a City Displaced: Shanghai in the 1950S 远去的都市:1950 年代的上海 (北京:社会科学文献出版社,2015)

The PRC History Review Book Review Series No. 24, August 2020. © The PRC History Group, 2020 BOOK REVIEW Zhang Jishun 张济顺, A City Displaced: Shanghai in the 1950s 远去的都市:1950 年代的上海 (北京:社会科学文献出版社,2015) Chuchu Wang, University of California, San Diego hanghai was not only the birthplace of Chinese Communist campaigns from 1952 to 1955, by distinguishing the reliable S Party (CCP), but also where the Party’s revolution from the problematic ones. The success of CCP’s transition and originally failed, forcing their flight from the city. “purification” facilitated the state’s penetration into society. Achieving military victory in the 1949, the CCP now needed to However, the individuals involved could exert their own agency govern an urban culture it once failed to tame. Zhang’s book, through participation in the state’s construction and A City Displaced: Shanghai in the 1950s, adopts the bottom-up mobilization process. The state’s intention and individuals’ social history approach to explore how different social groups own agency were not polarly opposed, and the goals of both in Shanghai reacted to or even actively engaged with CCP’s sides could be achieved, as Zhang demonstrates in this chapter. governance in the first decade of the People’s Republic. She clearly illustrates how society/individuals were actively involved in and contributed to the CCP’s triumph over As a person born in 1949 and an offspring of Shanghai’s itself/themselves. modern education forerunner Zhang Huanlun (张焕纶), Zhang wrote this book with nostalgia and passion. Throughout the Chapter 2 uses several cases to demonstrate how, in Shanghai’s book, Zhang coherently addresses three overriding themes: first election for the local People’s Congress, political reliability continuity before and after 1949; the relationship between was not crucial for total success.