Zhang Jishun 张济顺, a City Displaced: Shanghai in the 1950S 远去的都市:1950 年代的上海 (北京:社会科学文献出版社,2015)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Prominences1

THE THREE PROMINENCES1 Yizhong Gu The political-aesthetic principle of the “three prominences” (san tuchu 三突出) was the formula foremost in governing proletarian literature and art during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) (hereafter CR). In May 1968, Yu Huiyong 于会泳 initially proposed and defined the principle in this way: Among all characters, give prominence to the positive characters; among the positive characters, give prominence to the main heroic characters; among the main characters, give prominence to the most important character, namely, the central character.2 As the main composer of the Revolutionary Model Plays, Yu Hui- yong had gone through a number of ups and downs in the official hierarchy before finally receiving favor from Jiang Qing 江青, wife of Mao Zedong. Yu collected plenty of Jiang Qing’s concrete but scat- tered directions on the Model Plays and tried to summarize them in an abstract and formulaic pronouncement. The principle of three prominances was supposed to be applicable to all the Model Plays and thus give guidance for the creation of future proletarian artworks. Summarizing the gist of Jiang’s instruction, Yu observed, “Comrade Jiang Qing lays strong emphasis on the characterization of heroic fig- ures,” and therefore, “according to Comrade Jiang Qing’s directions, we generalize the ‘three prominences’ as an important principle upon which to build and characterize figures.”3 1 This essay owes much to invaluable encouragement and instruction from Profes- sors Ban Wang of Stanford University, Tani Barlow of Rice University, and Yomi Braester of the University of Washington. 2 Yu Huiyong, “Rang wenyi wutai yongyuan chengwei xuanchuan maozedong sixiang de zhendi” (Let the stage of art be the everlasting front to propagate the thought of Mao Zedong), Wenhui Bao (Wenhui daily) (May 23, 1968). -

2021 Edelman Award Ceremony for Distinction in Practice

2021 EDELMAN ogether, these awards demonstrate the power of advanced analytics at Intel, and its fundamental importance in our ability to deliver the technology AWARD Tleadership and reliable, top quality products the world needs and expects. CEREMONY — Kalani Ching, Intel Recognizing Distinction in the Practice of Analytics, Operations Research, and Management Science www.informs.org 2021 EDELMAN AWARD CEREMONY FOR DISTINCTION IN PRACTICE FRANZ EDELMAN AWARD Achievement in Advanced Analytics, Operations Research, & Management Science Emphasizing Beneficial Impact DANIEL H. WAGNER PRIZE Excellence in Operations Research Practice Emphasizing Innovative Methods and Clear Exposition UPS GEORGE D. SMITH PRIZE Strengthening Ties Between Academia & Industry Emphasizing Effective Academic Preparation INFORMS PRIZE Sustained Integration of Operations Research Emphasizing Long-Term, Multiproject Success The Edelman Award Ceremony 49 OCP 5 Ceremony Program 53 United Nations World Food Programme 6 Salute our Sponsors The Wagner Prize 7 Co-host—Dionne Aleman 57 Daniel H. Wagner Prize History 8 Co-host—Zahir Balaporia, CAP 58 2020 Wagner Prize Finalists Analytics and Operations Research Today 59 2020 Wagner Prize Winner 11 2021 Edelman Program Notes—Stephen Graves UPS George D. Smith Prize 14 Enriching the Lives of Every 63 UPS George D. Smith Prize History Person on Earth—Kalani Ching 65 2021 Smith Prize Competition 16 Operations Research: Billions and Billions of Benefits!—Jeffrey M. Alden 65 Smith Prize Past Winners TABLE OF Franz Edelman Award INFORMS Prize 19 Recognizing and Rewarding Real 71 INFORMS Prize History Achievement in O.R. and Analytics 71 INFORMS Prize Winners 20 The Finest Step Forward: Journey CONTENTS to the Franz Edelman Award 72 INFORMS Prize Criteria 23 Edelman First-Place Award Recipients 73 2021 INFORMS Prize Winner 26 The 2021 Selection Committee & Verifiers INFORMS 27 The 2021 Coaches & Judges 75 About INFORMS 29 The Edelman Laureates 76 Advancing the Practice of O.R. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript Pas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissenation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from anytype of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material bad to beremoved, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with smalloverlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell &Howell Information Company 300North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521·0600 THE LIN BIAO INCIDENT: A STUDY OF EXTRA-INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS IN THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AUGUST 1995 By Qiu Jin Dissertation Committee: Stephen Uhalley, Jr., Chairperson Harry Lamley Sharon Minichiello John Stephan Roger Ames UMI Number: 9604163 OMI Microform 9604163 Copyright 1995, by OMI Company. -

10M Air Rifle Women

XXXI O LYMPIC GAMES PR EVIEW DAY 1 SATURDAY, AUG 06 2016 EVENT INFORMATION AT 10:30 FINALS WORLD RANKING #1: Andrea ARSOVIC (SRB) TITLE DEFENDER: YI Siling (CHN) WORLD RECORD: 422.9 points scored by CHEN Dongqi (CHN) on 12/03/2014 FINALS WORLD RECORD: 211.0 points scored by YI Siling (CHN) on 03/07/2014 OLYMPIC RECORD: ISSF Rule Change - not established yet FINALS OLYMPIC RECORD: ISSF Rule Change - not established yet 10M AIR RIFLE WOMEN ust as in London four years ago, the participations occurred during the 2016 ISSF TOP FAVORITE 10m Air Women event will pres- World Cup Series: in Bangkok (THA), where ent the first Gold medal of the Rio she finished at the top the podium, and in Rio J2016 Olympic Games, following a long last- de Janeiro (BRA), where she placed 6th. ing tradition which was also upheld in Lon- A tangible threat to Yi’s ambitions will don, where the People’s Republic of China’s come in the shape of Serbia’s ANDREA YI SILING (27) received the first Gold medal ARSOVIC (27), current World Ranking leader of the Games. and winner of the World Cup Gold in the 10m Despite not having officially announced Air Rifle Women event in Munich (GER) last their Olympic selection yet, the Chinese na- June. tional team will probably be headlined by Yi Arsovic is going to lead a group of herself, current number 3 in the World Rank- contenders which will probably include Yi’s ing in this event and holder of the Finals teammate SHI MENGYAO (18), who made her World Record with 211.0 points. -

Download the Full Issue

East Asian History NUMBER 41 • AUGUST 2017 www.eastasianhistory.org CONTENTS 1–2 Guest Editor’s Preface Shih-Wen Sue Chen 3–14 ‘Aspiring to Enlightenment’: Buddhism and Atheism in 1980s China Scott Pacey 15–24 Activist Practitioners in the Qigong Boom of the 1980s Utiraruto Otehode and Benjamin Penny 25–40 Displaced Fantasy: Pulp Science Fiction in the Early Reform Era of the People’s Republic Of China Rui Kunze 王瑞 41–48 The Emergence of Independent Minds in the 1980s Liu Qing 刘擎 49–56 1984: What’s Been Lost and What’s Been Gained Sang Ye 桑晔 57–71 Intellectual Men and Women in the 1980s Fiction of Huang Beijia 黄蓓佳 Li Meng 李萌 online Chinese Magazines of the 1980s: An Online Exhibition only Curated by Shih-Wen Sue Chen Editor Benjamin Penny, The Australian National University Guest Editor Shih-Wen Sue Chen, Deakin University Editorial Assistant Lindy Allen Editorial Board Geremie R. Barmé (Founding Editor) Katarzyna Cwiertka (Leiden) Roald Maliangkay (ANU) Ivo Smits (Leiden) Tessa Morris-Suzuki (ANU) Design and production Lindy Allen and Katie Hayne Print PDFs based on an original design by Maureen MacKenzie-Taylor This is the forty-first issue of East Asian History, the fourth published in electronic form, August 2017. It continues the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. Contributions to www.eastasianhistory.org/contribute Back issues www.eastasianhistory.org/archive To cite this journal, use page numbers from PDF versions ISSN (electronic) 1839-9010 Copyright notice Copyright for the intellectual content of each paper is retained by its author. -

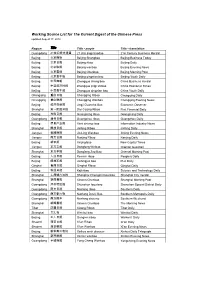

Working Source List for the Current Digest of the Chinese Press Updated August 17, 2012

Working Source List for The Current Digest of the Chinese Press updated August 17, 2012 Region Title Title - pinyin Title - translation Guangdong 21世纪经济报道 21 shiji jingji baodao 21st Century Business Herald Beijing 北京商报 Beijing Shangbao Beijing Business Today Beijing 北京日报 Beijing ribao Beijing Daily Beijing 北京晚报 Beijing wanbao Beijing Evening News Beijing 北京晨报 Beijing Chenbao Beijing Morning Post Beijing 北京青年报 Beijing qingnian bao Beijing Youth Daily Beijing 中国商報 Zhongguo shang bao China Business Herald Beijing 中国经济时报 Zhongguo jingji shibao China Economic Times Beijing 中国青年报 Zhongguo qingnian bao China Youth Daily Chongqing 重庆日报 Chongqing Ribao Chongqing Daily Chongqing 重庆晚报 Chongqing Wanbao Chongqing Evening News Beijing 经济观察报 Jingji Guancha Bao Economic Observer Shanghai 第一财经日报 Diyi Caijing Ribao First Financial Daily Beijing 光明日报 Guangming ribao Guangming Daily Guangdong 廣州日報 Guangzhou ribao Guangzhou Daily Beijing 信息产业报 Xinxi chanye bao Information Industry News Shanghai 解放日报 Jiefang Ribao Jiefang Daily Jiangsu 金陵晚报 Jin Ling Wanbao Jinling Evening News Jiangsu 南京日报 Nanjing Ribao Nanjing Daily Beijing 新京报 Xinjing bao New Capital Times Jiangsu 东方卫报 Dongfang Weibao Oriental Guardian Shanghai 东方早报 Dongfang Zao Bao Oriental Morning Post Beijing 人民日报 Renmin ribao People's Daily Beijing 解放军报 Jiefangjun bao PLA Daily Qinghai 青海日报 Qinghai Ribao Qinghai Daily Beijing 科技日报 Keji ribao Science and Technology Daily Shanghai 上海城市导报 Shanghai Chengshi Dao Bao Shanghai City Herald Shanghai 新闻晨报 Xinwen Chenbao Shanghai Morning Post Guangdong 深圳特区报 Shenzhen -

Olympische Spiele in Peking

1 Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite/n 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 3 – 4 Nominierung: Ovtcharov, Boll und Han führen deutsches Aufgebot zur EM nach Budapest 5 EM-Titelverteidiger und beste Deutsche 2015 5 Austragungsort Budapest 6 Wettbewerb + Modus 7 EM-Zeitplan 7 Geplante TV-Termine 9 Europa-Rangliste Herren/Damen Statistik 10 Deutsche Medaillengewinner bei Europameisterschaften 13 Achtelfinalisten bis Medaillengewinner des DTTB 13 Damen/Herren Einzel 16 Herren Doppel 17 Damen Doppel 18 Mixed Porträts 19 Porträts der deutschen Herren 25 Porträts der deutschen Damen 31 Porträts des Trainerteams 2 Nominierung Ovtcharov, Boll und Han führen deutsches Aufgebot zur EM nach Budapest Frankfurt/Budapest. Dimitrij Ovtcharov, Timo Boll und Han Ying führen die Aufgebote des Deutschen Tischtennis-Bundes bei den Europameisterschaften in Ungarns Hauptstadt Budapest (18. bis 23. Oktober) an. Das Bundestrainer-Team mit Jörg Roßkopf, Jie Schöpp und Sportdirektor Richard Prause schickt fünf Herren und fünf Damen bei der Individual-EM mit Einzel, Doppel und Mixed ins Rennen. Das Trio Ovtcharov (Orenburg), Boll (Düsseldorf) und Han (Tarnobrzeg) wird flankiert von Patrick Franziska (Saarbrücken), Steffen Mengel und Benedikt Duda (beide Bergneustadt), den Berlinerinnen Shan Xiaona und Petrissa Solja sowie Kolbermoors Sabine Winter und Kristin Silbereisen. Pause für Steger nach Olympia „Es ist eine schlagkräftige Truppe und eine gute Mischung aus vielen erfahrenen, aber auch jungen Kräften“, charakterisiert Richard Prause, Sportdirektor des Deutschen Tischtennis-Bundes, die Auswahl. Das lange Olympia-Jahr hat allerdings auch bei den mit zwei Medaillen in Rio dekorierten Deutschen Spuren hinterlassen. So verzichtet Rio-Fahrer Bastian Steger (Bremen) auf die EM und plant eine Regenerations- und Trainingsphase. Dimitrij Ovtcharov ist der Titelverteidiger im Einzel. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Academic nationalism Sleeboom, M.E. Publication date 2001 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Sleeboom, M. E. (2001). Academic nationalism. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 BIBLIOGRAPHY: European Languages Journals and translation services: Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs Current Anthropology CA China Quarterly CQ Chinese Sociology and Anthropology Discourse & Society FBIS Foreign Broadcast Information Service Foreign Affairs Issues & Studies l&S JPRS CPS Joint Publications Research Service: Chinese Politics and Society JPRS CST Joint Publications Research Service: Chinese Science and Technology Journal of Asian Studies Monumenta Nipponica The New Courant Peking Review SELMM Selected Materials from the Mainland (China) Social Science in China Strategy and Management S&M Volkskrant Altheide, D.L. -

2009 März Engl.Pmd

NEWS In this issue: Europe Top 12 02 2009 03 Düsseldorf - Review Europe Top 12 - Düsseldorf Preview German Open 04 Timo Boll triumphant for the fourth time „Tips and Tricks“ 05 World Champion Werner Schlager: Carrer The best European players had to go to the „cave of the lion“ to challenge Timo Boll at the Continental Ranking Tournament, the Europe Top 12. In the end Boll won his fourth title but the European Champion needed all the support he could get Products of the month 08 in a tricky situation. More about this on the next page! Butterfly in a new Internet Outfit! News/WRL (02/09) 12 Dear Ladies and Gentlemen, living table tennis Interview Part 13 Dear Table Tennis Friends! Timo Boll blades João Pedro Monteiro, Portugal Finally the time has come for our new internet appearance. While we were designing the web we paid Technique Tips 15 99 00 Werner Schlager’s forehand counter 00 special attention to make our internet pages dynamic, 22 jackets topspin at/over the table functional and individual for our customers. You are welcome to give us a feedback about our new pages. Butterfly inside 19 Best wishes, Hideyuki Kamizuru Summer Camp Neuheitenflyer_02_RZ.indd 1 19.01.09 16:13 www.butterfly-world.comProzessfarbe CyanProzessfarbe MagentaProzessfarbe GelbProzessfarbe Schwarz Redaktion/Editor - Am Schürmannshütt 30h - D-47441 Moers - Germany - Phone: +49 2841 90532-0 - Mail: [email protected] 02 Review Europe Top 12 Europe Top 12 2009 6. March - 8. March 2009 Timo Boll triumphant for the fourth time 77. National German Championship, Bielefeld The Butterfly on his chest lends Timo Boll its wings and the necessary support of the spectators gave him the needed back wind 11. -

Tuesday 25Th June – Quotes of the Day

Minsk 2019 2nd European Games Tuesday 25th June – Quotes of the Day by Milica Nikolic ETTU Press Officer 1.00 pm: Women’s Singles Semi-Final Yang Xiaoxin (Monaco) beat Polina Mikhailova (Russia) 11-7, 11-9, 11-1, 11-5 “I played her twice before in French League and won both times. I like to play against her style. I know what to do to win. Most important thing is to change the rhythm of the match constantly. I kept changing my service and kept changing the direction of my play. I changed forehand to backhand, went close to the table, then back. In second game she had a chance, she came close but after I won I think she just lost the edge to her game.” Yang Xiaoxin 1.00 pm: Women’s Singles Semi-Final Ni Xia Lian (Luxembourg) beat Linda Bergström (Sweden) 11-8, 11-7, 11-9, 5-11, 11-9 “I beat her already twice, so I had some mental advantage. Nevertheless, I was cautious. I knew I could not risk too much, I had to play conservatively and to be patient. Even though I was prepared, she surprised me a little. She has improved her game a great deal.” Ni Xia Lian 2.00 pm: Women’s Singles Semi-Final Han Ying (Germany) beat Li Jie (Netherlands) 11-5, 8-11, 14-12, 11-7, 11-5) “I tried to be more aggressive, not to be too passive. I have a mixed record against her. I beat her recently but I still remember our match from Baku when I lost.” Han Ying At the semi-final stage Han Ying meets Yang Xiaoxin “If I repeat my today’s game I do not have reason to worry. -

Summary of a Talk with the Representatives of Press and Publishing Circles

T E X T E I G H T Summary of a Talk with the Representatives of Press and Publishing Circles 10 MARCH 1957 [75] From 3:00 to 7:00 P.M. on 10 March, Chairman Mao held an informal discussion in his office with representatives of the press and publishing circles. Participating in this informal discussion were Jin Zhonghua,1 the representative of Shanghai's Xinwen ribao [Daily Sources: 9:75-90, alternate text, 7:46-59. A truncated version of this exchange has been pub lished in Mao Zedong xinwen gongzuo wenxuan (A selection of Mao Zedong's writings on news work) (Beijing, Xinhua chubanshe, 1983), pp. 186-95. The excisions made in the 1983 version seem designed to gloss over contemporary political problems. An even briefer ver sion of this text appears in the restricted circulation publication, Wenxian he yanjiu: 1983 huibianben (Documents and research: 1983 Selections) (Beijing, Renmin chubanshe, 1984), pp. 54-62. That this last neibu version is less complete than the public version serves as a warning that "restricted circulation'' does not guarantee greater completeness. 1Jin Zhonghua (b. 1902) was one of China's leading journalists. He had worked in the 1930s 250 TEXT EIGHT News] and China News Service; Wang Yunsheng, representative [of] Dagong bao,Z [and] Shanghai [76] Wenhui baa's representative, Xu Zhucheng.3 To start the discussion, the Chairman first invited the non-party personages from Shanghai to speak. The Chairman asked when Shanghai's Shen bao was abolished. [When he] heard the reply that Shen bao stopped publishing after Liberation, the Chairman remarked: There was no reason to abolish Shen bao, so old a paper of several decades' standing. -

The Legal Implications of China's Accession to the WTO* Pitman B

The Legal Implications of China’s Accession to the WTO* Pitman B. Potter China’s application for accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) raises particular questions about the implications for China’s legal system. This article examines these issues by reference to Chinese contexts and perspectives, and by examining the processes of accession and what these mean for further legal reform. It concludes with a discussion of possible approaches that might prove useful in managing China’s relationship with the world trading system. Contexts for China’s Accession to the WTO China’s effort to gain accession to the WTO stands against a back- ground of socio-economic and political conditions locally, and percep- tions about dependency and nationalism internationally. Associated with efforts to entrench policies of economic reform, WTO membership symbolizes contrasting policy preferences on China’s interaction with the world political economy, even while it raises for Chinese policy makers difficult questions about specific local costs and benefits. Chinese domestic conditions. China’s accession to the WTO should be viewed in light of domestic conditions.1 On the economic front, the ongoing and apparently intractable issue of state-owned enterprise reform and resulting conditions of unemployment and underemployment have created significant problems. The cost of investing to upgrade these enterprises is high and the level of foreign investment interest is marginal. The challenge of maintaining high growth rates while avoiding inflation continues to occupy China’s best economic planners. Public sector spend- ing on education and health care is lagging behind GDP growth, whereas the demographics of Chinese society suggest that these issues will require more investment, as increased economic competition places a greater premium on education and an ageing population puts greater burdens on the health care system.