From Diversity to Uniformity: a Study of Eap Courses from Diversity to Uniformity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bus 1: Mohawk & Redeemer Chris, David, Bruce

Directions for Drivers: Bus 1: Mohawk & Redeemer Chris, David, Bruce, Angel 10:45am- Arrival at Redeemer University College campus (777 Garner Rd E, Ancaster) Northwest Entrance parking lot, outside Auditorium 11:00am - Arrive at Mohawk College Campus (135 Fennell Avenue West) The Fennell drop off zone across from St. Josephs Healthcare 11:15am - Depart Mohawk Campus >>> Cotton Factory 11:30am - Arrive at The Cotton Factory (270 Sherman Ave N, Hamilton, ON L8L 6N4) Drop off at the main front door- It is a green door. Busses can park around the back once they unload. 1:30pm - Depart Cotton Factory >>> Collective Arts 1:40pm - Arrive at Collective Arts Brewing- (207 Burlington St E, Hamilton, ON L8L 4H2) Drop off at the side parking lot on Ferguson Ave N- The door to the “Beer Garden” 2:40pm - Depart Collective Arts >>> Kitestring 2:50pm - Arrive at Kitestring- (126 Catharine Street North, Hamilton ON L8R 1J4) 3:20pm – Depart Kitestring >>> AGH 3:45pm - Arrive at Art Gallery of Hamilton – (123 King St W, Hamilton, ON L8P 4S8) 4:30pm – Depart AGH>>> Mohawk 4:45pm - Arrive at Mohawk College Campus (135 Fennell Avenue West) The Fennell drop off zone across from St. Josephs Healthcare 4:50pm - Depart Mohawk>>> Redeemer 5:10pm - Arrival at Redeemer University College campus (777 Garner Rd E, Ancaster) Northwest Entrance parking lot, outside Auditorium Bus 2: McMaster Gisela, Teresa, Victoria 11:00am - Arrive at McMaster University (1280 Main St. W) Bus Circle in front of Ivor Wynne Centre 11:15am - Depart McMaster Campus >>> Cotton Factory 11:30am - Arrive at The Cotton Factory (270 Sherman Ave N, Hamilton, ON L8L 6N4) Drop off at the main front door- It is a green door. -

May 7 - Concurrent Session Schedule (1) Transitions In, Through & out of College (2) Student Development 51 Presenters Total (Not Including Dr

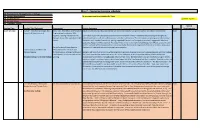

May 7 - Concurrent session schedule (1) Transitions In, Through & Out of College (2) Student Development 51 presenters total (not including Dr. Tinto) (3) Social Inclusion Updated: April 22 (4) Current Issues (5) Transition Toolkit Special Session Time Session Title/College(s) Presenter(s) Session Summary Location Requirements 11:15-12:15 pm 1 A1/A17 - Transition to College, Get Becca Allan, Orientation and Transition Together Centennial and Georgian College will share their transition programming from orientation to leadership. K318 Connected, Stay Connected Programming Coordinator, Mike Zecchino, Housing and Student Life Learn about Centennial's Road to Success transitions framework and our Leadership Passport program designed to Manager, Seona Morrison, Student Life connect students to each other, the institution and their communities. The cornerstones of getting started (Centennial Advisor Welcomes and Extended Orientation), getting supported (Service Fairs) and getting involved (Engagement Week and Leadership Passport) will be explored. The focus will be on the newly implemented Engagement Weeks, created to align with our semesterly break weeks and our innovative Leadership Passport program which results in students receiving a Darryl Creeden, Director Student Distinction in Leadership (second credential) at convocation. Transitioning to Academic and Recruitment and Transitions and Personal Success Christine Haesler, Manager of Student Georgian will share their 4 main transition programming events designed to connect incoming students with their college, Development, Transitions and Service staff, peers and the local community across all 7 of our campuses. It encourages the building of relationships and Georgian College, Centennial College Learning developing of connections making Georgian into their new home. Get Connected is our pre orientation program where we invite students on campus before classes have begun, but after they have picked their timetable. -

Loyalist College of Applied Arts and Technology – Annual Report 2018-19

LOYALIST COLLEGE ANNUAL REPORT 2018–2019 APPROVED JUNE 13, 2019 BOARD OF GOVERNORS ANNUAL REPORT 2018/19 LOYALIST COLLEGE OF APPLIED ARTS & TECHNOLOGY Contents 01 21 College Profile Building Capacity 02 23 A Message from the Board Increasing Transparency Chair and President 04 24 Skills and Job Outcome Sustainability Milestones Achievements 06 25 Innovations in Financial Health and Teaching and Learning Analysis of Financial Performance 08 28 Cluster-Based Applied Appendix A: Programs and Research 2018/19 Consolidated Highlights Financial Statements 16 30 Student Success Appendix B: 2018/19 Board of Governors 19 35 Employment and Appendix C: Training Support Advisory College Council Report 20 35 International Expansion Appendix D: Summary of Advertising and Marketing Complaints i ANNUAL REPORT 2018/19 LOYALIST COLLEGE OF APPLIED ARTS & TECHNOLOGY College Profile Loyalist College of Applied Arts & Technology is Ontario’s Destination College, empowering students, faculty, staff, and partners through experiential, industry cluster-based education, training and applied research programs. The College provides career-ready graduates for, and knowledge transfer to, industry and the community. Loyalist offers more than 70 full-time diploma, certificate and apprenticeship programs in biosciences, building sciences, business, community service, health and wellness, media studies, public safety, and skilled trades. Continuing education options are available through LoyalistFocus.com; including hundreds of online, distance and in-class courses; and through the College’s 100+ university transfer agreements. Located on more than 200 acres in the beautiful Bay of Quinte region, the College is perfectly positioned between Toronto, Ottawa and Montreal. As the region’s only post- secondary institution, Loyalist serves a population of 250,000, including the City of Belleville, City of Quinte West, Municipality of Brighton, Prince Edward County, Greater Napanee, and the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory. -

GRADUATE REPORT STATS and Testimonials

table of contents GRADUATE REPORT STATS and Testimonials SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE CENTRE FOR JUSTICE STUDIES GRADUATE TESTIMONIALS AND BUILDING SCIENCES Community & Justice Services Worker . .24 Bill Henderson ARCHITECTURE Corporate & Commercial Security . .24 Survey Engineering Technician . .2 Architectural Technician/Technology . .2 Customs & Immigration . .24 Kelly Sedore Residential Design & Drafting . .2 Paralegal . .24 Chemical Engineering Technology . .5 BUILDING SCIENCES Police Foundations . .26 Chad Duff, Environmental Technology . .6 Civil Engineering Technician/Technology . .2/3 Graduate Employers . .26/27 Nathalie Pye, Biotechnology Technology . .8 Construction Engineering Technician . .3 Kirsty Creamer Survey Engineering Technician . .3 SCHOOL OF MEDIA STUDIES Chemical Engineering Technology . .9 Graduate Employers . .3/4 Advertising . .29 Karen Hovinga Broadcast Journalism . .29 Culinary Skills-Chef Training . .12 Tenesa-Joy Gannon, Culinary Management . .14 SCHOOL OF BIOSCIENCES Photojournalism . .29 Isabelle Cloutier, Culinary Management . .14 Bio-Food Technician/Technology . .5 Print Journalism . .30 Courtney Cooper Biotechnology Technician/Technology . .5 Radio Broadcasting . .30 Business Sales & Marketing . .15 Chemical Engineering Technician/ Television & New Media Production . .30 Nancy File, Business Administration3 . .16 Technology . .6 POST-GRADUATE Matt Richardson, Business Administration . .17 Environmental Technician/Technology . .7 Public Relations . .30 Lorraine Downey, Paramedic . .19 Graduate Employers . .7/8 -

Loyalist College Annual Report 2019–2020

LOYALIST COLLEGE ANNUAL REPORT 2019–2020 APPROVED JUNE 24, 2020 BOARD OF GOVERNORS ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 LOYALIST COLLEGE OF APPLIED ARTS & TECHNOLOGY Contents 01 40 College Profile Financial Health and Analysis of Financial Performance 03 43 A Message from the Board Appendix A: 2019/20 Chair and President Consolidated Financial Statements 05 45 Highlights – Skills and Job Appendix B: 2019/20 Outcome Achievements Board of Governors 08 50 Highlights – Loyalist and Appendix C: College our Community Council Report 09 50 Loyalist College’s Appendix D: Summary of Strategic Directions Advertising and Marketing Complaints 37 COVID-19 and Loyalist College Response i ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 LOYALIST COLLEGE OF APPLIED ARTS & TECHNOLOGY College Profile Loyalist College of Applied Arts & Technology is Ontario’s Destination College, empowering students, faculty, staff, and partners through experiential, industry cluster-based education, training and applied research. The College provides career-ready graduates for, and knowledge transfer to, industry and the community. Loyalist offers more than 70 full-time diploma, certificate and apprenticeship programs in biosciences, building sciences, business, community service, health and wellness, media studies, public safety, and skilled trades. Distance and continuing education options are available through LoyalistFocus.com; including hundreds of online, distance and in-class courses; and through the College’s 100+ university transfer agreements. People and places are the forces that shape our lives. The greatest impact on the Loyalist educational experience is made by the students who learn with us, and the classrooms, labs and workshops where they study. The leading-edge facilities at Loyalist give access to the latest tools and technologies, learning resources, and realistic practice environments that prepare our students to be confident and effective in the workplace. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Gordon L. Heath Mcmaster Divinity College

CURRICULUM VITAE Gordon L. Heath McMaster Divinity College 1280 Main Street West Hamilton, Ontario, L8S4K1 [email protected] (905) 525-9140 x26409 20 August 2019 EDUCATION PhD, 2004 • University of St. Michael’s College at the University of Toronto MDiv (Honours), 1994 • Acadia University BTh, 1989 • Tyndale University College EMPLOYMENT McMaster Divinity College • Professor of Christian History, 2017 – present • Centenary Chair of World Christianity, 2013 – present • Director, Canadian Baptist Archives, 2004 – present • Associate Professor of Christian History, 2009 – 2017 • Assistant Professor of Christian History, 2004 – 2009 Tyndale University College • Assistant Professor of History, 2000 – 2004 • Director, Degree Completion Program, 2000 – 2004 • Adjunct Faculty, 1999 – 2000 TEACHING EXPERIENCE Undergraduate • History of Christianity • History of Christianity 1 • History of Christianity 2 • The Reformation • History of Evangelicalism • The Historian’s Craft: Historiography • Directed Research Project 2 Graduate • History of Christianity 1 • History of Christianity 2 • Foundations in Theology and History 1 • Foundations in Theology and History 2 • The Reformation • Christians and Violence • Christianity in the Canadian Context • Post-Christendom and the Canadian Church • History of Evangelicalism • Baptist History and Polity • Critical Events in Christian History • Women in Christian History • World and Writings of John Wesley • The Lives of the Saints: Then and Now • Ministry and Evangelical Thought • Evangelical Thought and Practice • Various Directed Studies classes • Presbyterianism in Canada (as a TA) PUBLICATIONS Authored Books • The British Nation is Our Nation: The BACSANZ Baptist Press and the South African War, 1899-1902. Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2017. • A War with a Silver Lining: Canadian Protestant Churches and the South African War, 1899-1902. Montreal/Kingston/London/Ithaca: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009. -

Press Release

For Immediate Release September 8, 2011 th Mechanical 17 Annual Mechanical Contractors Association Scholarship Awards Contractors Association Exceeds $323,000.00 Since Program’s Inception Hamilton SOUTHERN ONTARIO - The Mechanical Contractors Association of Hamilton (MCAH) serving members from Hamilton, Halton, Haldimand, Brant, and Norfolk Counties held their 17th Annual Scholarship Awards Ceremony at the Faculty Club of McMaster University. Twenty $1,000.00 scholarships were awarded to extraordinary students, children of salaried employees of MCAH Member Companies. Recipients are students either entering or currently enrolled in universities or colleges across Canada who maintained an exceptional grade average, established an outstanding commitment to their community through volunteerism and demonstrated superior interest in the mechanical contracting industry or their chosen field of study. This year, the MCA Hamilton McMaster Student Chapter $1,000 Scholarship also resulted in a tie. Lorraine Waller, MCAH President, hosted the awards and shares, “Again, we matched last year’s record-breaking 42 submissions, an increase measured over the past three years. Every year the recipient judging is difficult to say the least with the receipt of so (Photo) - 2011 MCAH Scholarship Recipients many accomplished applicants. The level of proficiency and achievement reached by these students this year has been absolutely top notch, both in their academic and community involvement. These students are progressive, optimistic thinkers, who know how to challenge themselves and have the results to prove it as testament to their discipline and determination.” This year’s Scholarship Selection Committee members having the difficult task included MCAH Director and Education Committee Chairman Bill Patterson, MCAH Past President Ron Marcotte and Education Committee members Anthony DeChellis, Manny Lemos and Rocco DiGiovanni. -

Services Available for Students with Lds at Ontario Colleges and Universities

Services Available for Students with LDs at Ontario Colleges and Universities Institution Student Accessibilities Services Website Student Accessibilities Services Contact Information Algoma University http://www.algomau.ca/learningcentre/ 705-949-2301 ext.4221 [email protected] Algonquin College http://www.algonquincollege.com/accessibility-office/ 613-727-4723 ext.7058 [email protected] Brock University https://brocku.ca/services-students-disabilities 905-668-5550 ext.3240 [email protected] Cambrian College http://www.cambriancollege.ca/AboutCambrian/Pages/Accessibilit 705-566-8101 ext.7420 y.aspx [email protected] Canadore College http://www.canadorecollege.ca/departments-services/student- College Drive Campus: success-services 705-474-7600 ext.5205 Resource Centre: 705-474-7600 ext.5544 Commerce Court Campus: 705-474-7600 ext.5655 Aviation Campus: 705-474-7600 ext.5956 Parry Sound Campus: 705-746-9222 ext.7351 Carleton University http://carleton.ca/accessibility/ 613-520-5622 [email protected] Centennial College https://www.centennialcollege.ca/student-life/student- Ashtonbee Campus: services/centre-for-students-with-disabilities/ 416-289-5000 ext.7202 Morningside Campus: 416-289-5000 ext.8025 Progress Campus: 416-289-5000 ext.2627 Story Arts Centre: 416-289-5000 ext.8664 [email protected] Services Available for Students with LDs at Ontario Colleges and Universities Conestoga College https://www.conestogac.on.ca/accessibility-services/ 519-748-5220 ext.3232 [email protected] Confederation -

The Corporation) on Sunday November 29, 2009, at 6:30 P.M., Local Time, for the Following Purposes

McMASTER STUDENTS UNION INCORPORATED TAKE NOTICE that there will be a meeting of McMASTER STUDENTS UNION INCORPORATED (the Corporation) on Sunday November 29, 2009, at 6:30 p.m., local time, for the following purposes. 1. To approve the amendments to the Agreement between the McMaster Students Union and the Mohawk Students Association. 2. To transact any further business that may properly come before the meeting Dated at Hamilton, Ontario, this 16th day of November, 2009 BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS. ______________________ Julianne Simpson Corporate Secretary MOTIONS 1. Moved by Richardson, seconded by Tenenbaum to approve the amendments to the Agreement between the McMaster Students Union and the Mohawk Students Association as presented and attached. AGREEMENT between the McMaster Students Union and the Mohawk Students’ Association 1.0 INTRODUCTION Whereas the McMaster Students Union operates several student services and operations at the McMaster University campus in Hamilton and Mohawk Students’ Association operates several student services and operations at the Mohawk College campus in Hamilton; Whereas students of Mohawk College will be attending classes at the McMaster University campus and students of McMaster University will be attending classes at Mohawk college campus ; Whereas the Mohawk Students’ Association wishes to contract the McMaster Students Union to provide certain services for the aforementioned students and the McMaster Students Union wishes to contract the Mohawk Students’ Association to provide certain services for the aforementioned students; Herein contained are the terms and conditions on which the McMaster Students Union and Mohawk Students’ Association agree. 2.0 DEFINITIONS “MSU” shall refer to the McMaster Students Union. -

OC C Me Mbe Rs H Ip Dire C to Ry 201 9

20 - 20 – 2019 2019 CCCO des Directory Membres des Membership Ontario College Counsellor Directory OCC 2019-20 Répertoire des Membres des Conseillers et Conseillères des Collèges de l'Ontario Répertoire OCC-CCCO Executive Officers 2019-2020 Chair Maheen Sayal, Sheridan College (905) 459-7533 Ext. 2891 [email protected] Past Chair Shawna Bernard, Conestoga College (519) 748-5220 Ext. 3236 [email protected] Secretary Greg Taylor, Georgian College (705) 728-1968 Ext. 1626 [email protected] Webmaster / Social Media Consultant Heather Drummond, Mohawk College (905) 575-2102 [email protected] Registrar Jennifer Babin, Niagara College (905) 641-2252 Ext.4167 [email protected] Treasurer John Muldoon, Algonquin College (613) 727-4723 Ext.6275 [email protected] Between Us/Entre Nous Editors Candice Lawrence, Fanshawe College (519) 452-4430 Ext. 4307 [email protected] HOSA Liaison Bonnie Lipton-Bos, Conestoga College (519) 748-5220 Ext: 2269 [email protected] Professional Development Liaison Lavlet Forde, George Brown College (416) 675-6622 Ext. 4743 [email protected] Sue Furs, Seneca College (416) 491-5050 Ext. 33095 [email protected] Regional Representatives Northern Representative Darryl MacNeil, Confederation College (807) 475-6438 [email protected] Eastern Representative John Muldoon, Algonquin College (613) 727-4723 Ext. 6275 [email protected] Central Representative Alyse Nishimura, Sheridan College (905) 845-9430 Ext. 2696 [email protected] Southwestern Representative Candice Lawrence, Fanshawe College (519) 452-4430 Ext. 4307 [email protected] Indigenous Representative Jamie Warren, Niagara College (905) 735-2211 Ext. 7774 [email protected] Francophone Representative Katherine Whiteside, Georgian College (705) 325-2740 Ext. -

Action Recommendations Report April 2016

Change Camp Hamilton 2016 A Conversation on Community, Partnerships, and Collaboration Action Recommendations Report April 2016 Compiled by Change Camp Hamilton Steering Committee Dave Heidebrecht, McMaster University (Chair) Luke Baylis, Mohawk Students’ Association Irene Heffernan, City of Hamilton Spencer Nestico-Semianiw, McMaster Students Union Alexia Olaizola, McMaster Students Union Annelisa Pedersen, City of Hamilton John Schuurman, Redeemer University College and Planning Team Jennifer Canning, McMaster University Karen Cornies, Redeemer University College Laura Ryan, Social Planning and Research Council of Hamilton Lyna Saad, Social Planning and Research Council of Hamilton Sheila Sammon, McMaster University Lauren Soluk, Mohawk College Change Camp Hamilton 2016 | Action Recommendations Report Page 1 of 22 THANK YOU to our volunteer facilitators and support team: John Ariyo, City of Hamilton Cindy Mutch, City of Hamilton Diedre Beintema, City of Hamilton Rodrigo Narro Perez, McMaster University Johanna Benjamins, Redeemer University Daymon Oliveros, McMaster Students College Union Jacob Brodka, McMaster University Katie Pita, McMaster Students Union Jay Carter, Evergreen Cityworks Huzaifa Saeed, Hamilton Chamber of Don Curry, City of Hamilton Commerce Kyle Datzkiw, Mohawk Students’ Natalie Shearer, Mohawk College Association Jocelyn Strutt, City of Hamilton Carajane Dempsey, McMaster University Wayne Terryberry, McMaster University Heather Donison, City of Hamilton Pete Topalovic, City of Hamilton Katherine Flynn, Mohawk College -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents: Co-op Program Contacts ................................................................................................................................2 College Message and Co-op Services ..........................................................................................................3 Mohawk Co-op Process ..................................................................................................................................4 Co-operative Education Tax Credit (CETC) ..................................................................................................5 On-Campus Employee Recruitment and Career Fairs ................................................................................6 Posting Full-Time, Part-Time and Seasonal Jobs ........................................................................................7 Employer Services ...........................................................................................................................................8 Maps and Directions .....................................................................................................................................62 Co-op Program Descriptions BUSINESS, MEDIA AND ENTERTAINMENT Business Business – Accounting ...................................................................................................................18 Business – Marketing .....................................................................................................................20 Insurance .........................................................................................................................................22