Bring Back the Streetcars : a Conservative Vision of Tomorrow's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can Public Transit Revitalize Detroit? the Qline and the People Mover”

“Can Public Transit Revitalize Detroit? The QLine and the People Mover” John B. Sutcliffe, Sarah Cipkar and Geoffrey Alchin Department of Political Science, University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, N9B 3P4 Email: [email protected] Paper prepared for presentation at the Canadian Political Science Association Annual Conference, Vancouver, BC. June 2019. This is a working draft. Please do not cite without permission. 1 “Can Public Transit Revitalize Detroit? The QLine and the People Mover" Introduction On May 12, 2017 a new streetcar – the QLine – began operating in Detroit, running along a 3.3- mile (6.6-mile return) route on Woodward Avenue, one of the central north-south roads in the city. This project is one example of the return to prominence of streetcars in the (re)development of American cities. Having fallen into disuse and abandonment in hundreds of American cities during the early part of the 20th century, this form of public transit has returned in many cities including, for example, Dallas, Cincinnati, Kansas City, and Portland. As streetcar services have returned to prominence, so too has the debate about their utility as a form of public transit, the function they serve in a city, and who they serve (Brown 2013; Culver 2017). These debates are evident in the case of Detroit. Proponents of the QLine – most prominently the individuals and organizations that advocated for its creation and provided the majority of the start-up capital – have praised the streetcar for acting as a spur to development, for being a forward-thinking transit system and for acting as a first step towards a comprehensive regional transit system in Metro Detroit (see M-1 Rail 2018). -

10 – Eurocruise - Porto Part 4 - Heritage Streetcar Operations

10 – Eurocruise - Porto Part 4 - Heritage Streetcar Operations On Wednesday morning Luis joined us at breakfast in our hotel, and we walked a couple of blocks in a light fog to a stop on the 22 line. The STCP heritage system consists of three routes, numbered 1, 18 and 22. The first two are similar to corresponding services from the days when standard- gauge streetcars were the most important element in Porto’s transit system. See http://www.urbanrail.net/eu/pt/porto/porto-tram.htm. The three connecting heritage lines run every half-hour, 7 days per week, starting a little after the morning rush hour. Routes 1 and 18 are single track with passing sidings, while the 22 is a one-way loop, with a short single-track stub at its outer end. At its Carmo end the 18 also traverses a one-way loop through various streets. Like Lisbon, the tramway operated a combination of single- and double- truck Brill-type cars in its heyday, but now regular service consists of only the deck-roofed 4-wheelers, which have been equipped with magnetic track brakes. Four such units are operated each day, as the 1 line is sufficiently long to need two cars. The cars on the road on Wednesday were 131, 205, 213 and 220. All were built by the CCFP (Porto’s Carris) from Brill blueprints. The 131 was completed in 1910, while the others came out of the shops in the late 1930s-early 1940s. Porto also has an excellent tram museum, which is adjacent to the Massarelos carhouse, where the rolling stock for the heritage operation is maintained. -

Other Trams in the Bendigo Fleet

Other trams in the Bendigo Fleet The status of the trams in the list below are one of the following: A. In storage B. Being restored/awaiting restoration C. On static display at the tramways D. On loan or lease to other tramways Tram Number: Historic and technical details: #2 Status: In storage Maximum Traction Bogie Tram History: This tram first operated in Melbourne as Hawthorn Tramways Trust #20. With the formation of the Melbourne and Metropolitan Tramways Board, it became M&MTB # 126. It was sold to the SECV Geelong Tramways in 1947 to become #34. Upon the closure of the Geelong Tramways in 1956, the tram was transferred to Bendigo where it became #2. Builder: Duncan & Fraser, Adelaide, South Australia (1916) for the Hawthorn Tramways Trust as #20. Technical Information: Trucks - Brill 22E. Motors - 2 X 65 hp GE 201. Controllers - GE B23E. Braking - hand brakes and air operated manual-lapping valves. Weight - 16.0 tonnes. Length - 13.59 metres. #3 Status: Undergoing restoration at the main depot. Single Truck Battery Tram History: Tram services using these trams commenced in June 1890 but because of the inefficiency of the battery trams, the entire system was abandoned in September 1890 and the assets sold to the Bendigo Tramway Company Limited. Builder: Brush Electrical Engineering Company Limited, Loughborough, United Kingdom (1889) for the Sandhurst and Eaglehawk Tramway Company Limited (S&ETCo Ltd) as #3. Technical Information: The trams were powered by a single motor, with a wheel operated controller located on each platform. Braking was obtained by the use of a hand brake also located on each platform. -

Comparison Between Bus Rapid Transit and Light-Rail Transit Systems: a Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Approach

Urban Transport XXIII 143 COMPARISON BETWEEN BUS RAPID TRANSIT AND LIGHT-RAIL TRANSIT SYSTEMS: A MULTI-CRITERIA DECISION ANALYSIS APPROACH MARÍA EUGENIA LÓPEZ LAMBAS1, NADIA GIUFFRIDA2, MATTEO IGNACCOLO2 & GIUSEPPE INTURRI2 1TRANSyT, Transport Research Centre, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Spain 2Department of Civil Engineering and Architecture (DICAR), University of Catania, Italy ABSTRACT The construction choice between two different transport systems in urban areas, as in the case of Light-Rail Transit (LRT) and Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) solutions, is often performed on the basis of cost-benefit analysis and geometrical constraints due to the available space for the infrastructure. Classical economic analysis techniques are often unable to take into account some of the non-monetary parameters which have a huge impact on the final result of the choice, since they often include social acceptance and sustainability aspects. The application of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) techniques can aid decision makers in the selection process, with the possibility to compare non-homogeneous criteria, both qualitative and quantitative, and allowing the generation of an objective ranking of the different alternatives. The coupling of MCDA and Geographic Information System (GIS) environments also permits an easier and faster analysis of spatial parameters, and a clearer representation of indicator comparisons. Based on these assumptions, a LRT and BRT system will be analysed according to their own transportation, economic, social and environmental impacts as a hypothetical exercise; moreover, through the use of MCDA techniques a global score for both systems will be determined, in order to allow for a fully comprehensive comparison. Keywords: BHLS, urban transport, transit systems, TOPSIS. -

The Stepped Hull Hybrid Hydrofoil

The Stepped Hull Hybrid Hydrofoil Christopher D. Barry, Bryan Duffty Planing @brid hydrofoils or partially hydrofoil supported planing boat are hydrofoils that intentionally operate in what would be the takeoff condition for a norma[ hydrofoil. They ofler a compromise ofperformance and cost that might be appropriate for ferq missions. The stepped hybrid configuration has made appearances in the high speed boat scene as early as 1938. It is a solution to the problems of instability and inefficiency that has limited other type of hybrids. It can be configured to have good seakeeping as well, but the concept has not been used as widely as would be justified by its merits. The purpose of this paper is to reintroduce this concept to the marine community, particularly for small, fast ferries. We have performed analytic studies, simple model experiments and manned experiments, andfiom them have determined some specljic problems and issues for the practical implementation of this concept. This paper presents background information, discusses key concepts including resistance, stability, seakeeping, and propulsion and suggests solutions to what we believe are the problems that have limited the widespread acceptance of this concept. Finally we propose a “strawman” design for a ferry in a particular service using this technology. BACKGROUND Partially hydrofoil supported planing hulls mix hydrofoil support and planing lift. The most obvious A hybrid hydrofoil is a vehicle combining the version of this concept is a planing hull with a dynamic lift of hydrofoils with a significant amount of hydrofoil more or less under the center of gravity. lit? tiom some other source, generally either buoyancy Karafiath (1974) studied this concept and ran model or planing lift. -

Woodland Ferry History

Woodland Ferry: Crossing the Nanticoke River from the 1740s to the present Carolann Wicks Secretary, Department of Transportation Welcome! This short history of the Woodland Ferry, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, was written to mark the commissioning of a new ferryboat, the Tina Fallon, in 2008. It is an interesting and colorful story. TIMELINE 1608 Captain John Smith explores 1843 Jacob Cannon Jr. murdered at the the Nanticoke River, and encounters wharf. Brother Isaac Cannon dies one Nanticoke Indians. Native Americans month later. Ferry passes to their sister have resided in the region for thousands Luraney Boling of years 1845 Inventory of Luraney Boling’s 1734 James Cannon purchases a estate includes “one wood scow, one land tract called Cannon’s Regulation at schooner, one large old scow, two small Woodland old scows, one ferry scow, one old and worn out chain cable, one lot of old cable 1743? James Cannon starts operating a chains and two scow chains, on and ferry about the wharves” 1748 A wharf is mentioned at the 1883 Delaware General Assembly ferry passes an act authorizing the Levy Court of Sussex County to establish and 1751 James Cannon dies and his son maintain a ferry at Woodland Jacob takes over the ferry 1885 William Ellis paid an annual 1766 A tax of 1,500 lbs. of tobacco salary of $119.99 by Sussex County for is paid “to Jacob Cannon for keeping operating the ferry a Ferry over Nanticoke River the Year past” 1930 Model “T” engine attached to the wooden ferryboat 1780 Jacob Cannon dies and -

A Ride Through Victoria's Tramway Culture

Trammies A ride through Victoria’s tramway culture Trammies tells of Victoria’s rich and colourful tramway history from 1885 to the present. Discover when trams started, why they survived against the odds and the characters who continue to work on them. 21 February – 11 May 2003 The Trammie Family The trammie family is an experience for many of us who put on the tram uniform. Our common costume helps identify us to the public and to our co-workers, while shiftwork has us out and about at odd times; early morning, late at night, and of course during the day. Trammies meet with Melbourne’s citizenry every day, as well as the many visitors to our city that jump on for a ride. Trammies gather around the pool table at the Malvern Depot. Trammies work from Melbourne’s eight tram depots, while others work at the Preston Workshops, Civil Branch and the Overhead Electrical Department. Together they share the day’s experiences and have the long standing tradition of socialising through tramway social clubs, inter-depot competitions, balls, picnics and barbeques. This social tradition was encouraged in the days of the Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board who actively sought to develop and encourage a harmonious ‘trammie family'. East Preston Depot vs South Melbourne Depot football match, 1995. South won! Ballarat Tramways Social Club, Grenville Street, Excerpts from the MMTB News, 1964 and 1967. c.1930s. Courtesy of Ballarat Tramway Museum. Melbourne’s 2003 Depots Brunswick Camberwell East Preston Essendon Glenhuntly Kew Malvern Southbank Melbourne – A Rare Tramway Survivor The changing fortunes of trams The Melbourne tramway system is the only surviving complete tramway system in the English-speaking world. -

The Transfer Newsletter Spring 2013.Cdr

Oregon Electric Railway Historical Society Volume 18 503 Issue 2 Spring 2013 Reminder to members: Please be sure your dues In this issue: are up to date. 2013 dues were due Jan 1, 2013. Willamette Shore Trolley - Back on Track.................................1 If it has been longer than one year since you renewed, Interpretive Center Update - Greg Bonn...............................2 go to our website: oerhs.org and download an Vintage Trolley History - Richard Thompson.............................3 application by clicking: Become a Member Pacific NW Transit Update - Roy Bonn...............................8 Spotlight on Members: Charlie Philpot ................................11 Setting New Poles - Greg Bonn..............................................12 Willamette Shore Trolley ....back on track! See this issue in color on line at oerhs.org/transfer miles from Lake Oswego to Riverwood Crossing with an ultimate plan to extend to Portland. Also see the article on page 3 on the history of the cars of Vintage Trolley. Dave Rowe installing wires from Generator to Trolley. Hal Rosene at the controls of 514 on a training run emerging Gage Giest painting from the Elk Rock Tunnel on the Willamette Shore line. the front of Trolley. Wayne Jones photo The Flume car in background will be After a several-year hiatus, the Willamette Shore our emergency tow Trolley is just about ready to roll. Last minute electrical and vehicle if the Trolley mechanical details and regulatory compliance testing are breaks down on the nearing completion. With many stakeholders involved and mainline. many technical issues that had to be overcome, it has been a challenge to get the system to the 100% state. Dave Rowe and his team have been working long hours to overcome the obstacles of getting Gomaco built Vintage Trolley #514, its Doug Allen removing old stickers from side tag-along generator, track work, electrical systems, crew of Trolley training, safety compliance issues, propulsion, braking, and so many other details to a satisfactory state to begin revenue service. -

January–June 2005 · $10.00 / Rails To

January–June 2005 · $10.00 / Rails to Rubber to Rails Again, Part 1: Alabama–Montana Headlights The Magazine of Electric Railways Published since 1939 by the Electric Railroaders’ Association, Inc. WWW.ERAUSA.ORG Staff Contents Editor and Art Director January–June 2005 Sandy Campbell Associate Editors Raymond R. Berger, Frank S. Miklos, John Pappas Contributors Edward Ridolph, Trevor Logan, Bill Volkmer, Columns Alan K. Weeks 2 News Electric Railroaders’ Compiled by Frank Miklos. International transportation reports. Association, Inc. E Two-Part Cover Story Board of Directors 2008 President 18 Rails to Rubber to Rails Again Frank S. Miklos By Edward Ridolph. An extensive 60-year summary of the street railway industry in First Vice President the U.S. and Canada, starting with its precipitous 30-year, post-World War II decline. William K. Guild It continues with the industry’s rebirth under the banner of “light rail” in the early Second Vice President & Corresponding Secretary 1980s, a renaissance which continues to this day. Raymond R. Berger Third Vice President & Recording Secretary Robert J. Newhouser Below: LAMTA P3 3156 is eastbound across the First Street bridge over the Los Treasurer Angeles River in the waning weeks of service before abandonment of Los Angeles’ Michael Glikin narrow gauge system on March 31, 1963. GERALD SQUIER PHOTO Director Jeffrey Erlitz Membership Secretary Sandy Campbell Officers 2008 Trip & Convention Chairman Jack May Librarian William K. Guild Manager of Publication Sales Raymond R. Berger Overseas Liason Officer James Mattina National Headquarters Grand Central Terminal, New York City A-Tower, Room 4A Mailing Address P.O. -

Bus/Light Rail Integration Lynx Blue Line Extension Reference Effective March 19, 2018

2/18 www.ridetransit.org 704-336-RIDE (7433) | 866-779-CATS (2287) 866-779-CATS | (7433) 704-336-RIDE BUS/LIGHT RAIL INTEGRATION LYNX BLUE LINE EXTENSION REFERENCE EFFECTIVE MARCH 19, 2018 INTEGRACIÓN AUTOBÚS/FERROCARRIL LIGERO REFERENCIA DE LA EXTENSIÓN DE LA LÍNEA LYNX BLUE EN VIGOR A PARTIR DEL 19 DE MARZO DE 2018 On March 19, 2018, CATS will be introducing several bus service improvements to coincide with the opening of the LYNX Blue Line Light Rail Extension. These improvements will assist you with direct connections and improved travel time. Please review the following maps and service descriptions to learn more. El 19 de marzo de 2018 CATS introducirá varias mejoras al servicio de autobuses que coincidirán con la apertura de la extensión de ferrocarril ligero de la línea LYNX Blue. Estas mejoras lo ayudarán con conexiones directas y un mejor tiempo de viaje. Consulte los siguientes mapas y descripciones de servicios para obtener más información. TABLE OF CONTENTS ÍNDICE Discontinued Bus Routes ....................................1 Rutas de autobús discontinuadas ......................1 54X University Research Park | 80X Concord Express 54X University Research Park | 80X Concord Express 201 Garden City | 204 LaSalle | 232 Grier Heights 201 Garden City | 204 LaSalle | 232 Grier Heights Service Improvements .........................................2 Mejoras al servicio ...............................................2 LYNX Blue Line | 3 The Plaza | 9 Central Ave LYNX Blue Line | 3 The Plaza | 9 Central Ave 11 North Tryon | 13 Nevin -

115 Welcome the Following Mem Bers to the Museum:- APRIL 1968

2 TROLLEY WIRE APRIL I968 help ! The Museum work force desperately needs the as sistance of members in three major works projects being undertaken at Loftus. The depot is to be rebuilt, preliminary work has already been undertaken but we still need several members to assist. The depot junction pointwork is presently being rebuilt. Remember this work must be completed before we can begin regular running of interstate cars on our sys tem, The Brisbane car, 180, needs a lot of time spent on it to strip off all the paint, inside and out, before minor repairs to bodywork and electrical etc, can be carried out. The regular workforce (all five of them....yes, FIVE of them) would be grateful for your help. ELECTION OF DIRECTORS The ninth annual meeting of the South Pacific Electric Railway Co-operative Society Limited will be held at 8.00 pm on Friday 28th June, 1968 at a venue to be ad vised . Any shareholder wishing to stand for election to the position of director should satisfy the following re quirements :- 1. He must be a financial member with all current museum financial requirements fully settled. 2. He must lodge his nomination with the Secretary at Box 103, G.P.O., Sydney, 2001 by 31st May, I968, bearing his own signature as well as those of a nominator and a seconder, both af whom must satisfy the requirements of part 1 above. 3. Those nominating for election, as well as the nominator and seconder must be 21 years of age or over on 31st May, I968. -

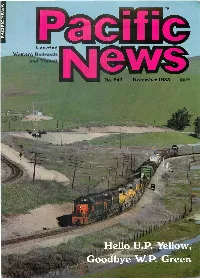

$2.00 New from Random House This Fall

__- - e tern Railroads and Transit , I $2.00 New From Random House this fall .... THIRTY THREE LIFE STORIES OF THE PEOPLE THAT MADE OVER THE TRAINS 150 RUN. PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE INTRODUCTION BY STUART LEUTHNER "This is not a railroad book.It is a railroaders book. It is about the people who worked for the railroads. The engineers, brakemen, chefs, executives, the people who made it work. With a few exceptions, books dealing with the railroads have become cavalcades of iron. Page after page of locomotives, leaning into curves, in the roundhouse, at the coaling dock.You name it, it's been photographed. A typical caption: 'Rods flashing, high-drivered Pennsy K-4s No.5404 wheels the varnishas she hits her stride with the Broadway Limited near the Horseshoe Curve on an old February afternoon, 1945' .... "The railroads were one of the most important industries in this country when these people were on the job.Even into the 1950's, they were a complicated system of machinery and people stretching over the entire country. It's been an undisputed fact that without the railroads' superhuman efforts, World War" might not have been won.The railroads worked the way they did because the people worked. Worked in the true meaning of the word. There was only ...." " r----- ------------------ Bonanza Inn Bookshop -� I .. 650 Market Street •••• 11-•• Ii•• • I !I.,,-.f.jj I San Francisco 941 04 -:-g�g-::-�"'" '- I I ON TRAINS I Please send copies of The Railroaders @$1 9.95, plus BOOIS IiTROLLEYS I $1 .1 5 total shipping charge for any quantity.