Hawkins 1.4 Charisma Validity 20110512

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disrupting the Party: a Case Study of Ahora Madrid and Its Participatory Innovations

Disrupting the Party: A Case Study of Ahora Madrid and Its Participatory Innovations Quinton Mayne and Cecilia Nicolini September 2020 Disrupting the Party: A Case Study of Ahora Madrid and Its Participatory Innovations Quinton Mayne and Cecilia Nicolini September 2020 disrupting the party: A Case Study of Ahora Madrid and Its Participatory Innovations letter from the editor The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excel- lence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. By training the very best leaders, developing powerful new ideas, and disseminating innovative solutions and institutional reforms, the Ash Center’s goal is to meet the profound challenges facing the world’s citizens. Our Occasional Papers Series highlights new research and commentary that we hope will engage our readers and prompt an energetic exchange of ideas in the public policy community. This paper is contributed by Quinton Mayne, Ford Foundation Associate Profes- sor of Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School and an Ash Center faculty associate, and Cecilia Nicolini, a former Ash Center Research Fellow and a current advisor to the president of Argentina. The paper addresses issues that lie at the heart of the work of the Ash Center—urban governance, democratic deepening, participatory innova- tions, and civic technology. It does this through a study of the fascinating rise of Ahora Madrid, a progressive electoral alliance that—to the surprise of onlookers—managed to gain political control, just a few months after being formed, of the Spanish capital following the 2015 municipal elections. Headed by the unassuming figure of Manuela Carmena, a former judge, Ahora Madrid won voters over with a bold agenda that reimagined the relationship between citizens and city hall. -

The Year in Elections, 2013: the World's Flawed and Failed Contests

The Year in Elections, 2013: The World's Flawed and Failed Contests The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Norris, Pippa, Richard W. Frank, and Ferran Martinez i Coma. 2014. The Year in Elections 2013: The World's Flawed and Failed Contests. The Electoral Integrity Project. Published Version http://www.electoralintegrityproject.com/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11744445 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA THE YEAR IN ELECTIONS, 2013 THE WORLD’S FLAWED AND FAILED CONTESTS Pippa Norris, Richard W. Frank, and Ferran Martínez i Coma February 2014 THE YEAR IN ELECTIONS, 2013 WWW. ELECTORALINTEGRITYPROJECT.COM The Electoral Integrity Project Department of Government and International Relations Merewether Building, HO4 University of Sydney, NSW 2006 Phone: +61(2) 9351 6041 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.electoralintegrityproject.com Copyright © Pippa Norris, Ferran Martínez i Coma, and Richard W. Frank 2014. All rights reserved. Photo credits Cover photo: ‘Ballot for national election.’ by Daniel Littlewood, http://www.flickr.com/photos/daniellittlewood/413339945. Licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0. Page 6 and 18: ‘Ballot sections are separated for counting.’ by Brittany Danisch, http://www.flickr.com/photos/bdanisch/6084970163/ Licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0. Page 8: ‘Women in Pakistan wait to vote’ by DFID - UK Department for International Development, http://www.flickr.com/photos/dfid/8735821208/ Licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0. -

Mali 2013: a Year of Elections and Further Challenges Written by Morten Boas

Mali 2013: A Year of Elections and Further Challenges Written by Morten Boas This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Mali 2013: A Year of Elections and Further Challenges https://www.e-ir.info/2013/12/22/mali-2013-a-year-of-elections-and-further-challenges/ MORTEN BOAS, DEC 22 2013 Emerging from a severe political crisis that had a severe impact upon the country for almost a year and a half, Mali staged a remarkable comeback during the summer of 2013 when the country held successful presidential elections. The winner was Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, and the large majority he collected gave his mandate legitimacy. The challenges are, however, still huge; the upsurge in violence that accompanied the parliamentary elections testifies to this, but the Islamic insurgents are not the only bump in the road to the Malian recovery. Political and administrative institutions must be rebuilt, the army must be brought under constitutional control, and President Keita must find a constructive way of dealing with the Tuareg rebels in the north. His main challenge in this regard is that his room for manoeuvring is constrained by his own supporters who will not accept a deal that gives autonomy to the areas to which the Tuareg lay claim. The Malian Crisis The Malian crisis was a crisis of multiple dimensions, with each feeding the others. It started in the north with a rebellion originally based on Tuareg grievances, but as the Malian army fled south, Islamist-inspired insurgents took control of large parts of northern Mali. -

Rise of Illiberal Civil Society W

Executive Summary This publication examines the growing influence of illiberal, anti-Western and socially conservative civil society groups, popular movements and political forces in five post-Soviet states: Georgia, Armenia, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan and Moldova. It finds that illiberal social attitudes remain prevalent across the region, particularly in relation to LGBTI rights, and that they are increasingly being used as opportunities for political mobilisation within these societies. While there have been attempts to create illiberal civil society groups that mirror pro- Western/liberal NGOs or think-tanks, they remain significantly less influential than the institutions and groups linked to the dominant religious organisations in these countries such as the Orthodox Church, or political factions with influence over state resources. What is clear, however, particularly in Ukraine and Georgia, is that there has been a significant rise in far-right and nationalist street movements, alongside smaller but active homophobic gangs. These ‘uncivil rights movements’ still lack broad public support but their political energy and rate of growth is influencing the wider politics of the region. It is clear that illiberal civil society is on the rise in these five countries but it is growing in its own way rather than simply aping its liberal counterparts. Russia has an important role in the rise of illiberal civil society across the region, in particular the way it has disseminated and promoted the concept of ‘traditional values’; however it is important to recognise that while some groups have direct or indirect contact with Russia, many do not and that the primary drivers of such activity are to be found in the local societies of the countries at hand. -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

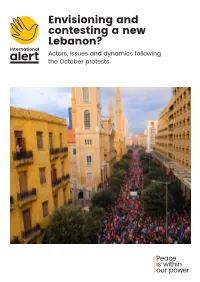

Envisioning and Contesting a New Lebanon? Actors, Issues and Dynamics Following the October Protests About International Alert

Envisioning and contesting a new Lebanon? Actors, issues and dynamics following the October protests About International Alert International Alert works with people directly affected by conflict to build lasting peace. We focus on solving the root causes of conflict, bringing together people from across divides. From the grassroots to policy level, we come together to build everyday peace. Peace is just as much about communities living together, side by side, and resolving their differences without resorting to violence, as it is about people signing a treaty or laying down their arms. That is why we believe that we all have a role to play in building a more peaceful future. www.international-alert.org © International Alert 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without full attribution. Layout: Marc Rechdane Front cover image: © Ali Hamouch Envisioning and contesting a new Lebanon? Actors, issues and dynamics following the October protests Muzna Al-Masri, Zeina Abla and Rana Hassan August 2020 2 | International Alert Envisioning and contesting a new Lebanon? Acknowledgements International Alert would like to thank the research team: Muzna Al-Masri, Zeina Abla and Rana Hassan, as well as Aseel Naamani, Ruth Simpson and Ilina Slavova from International Alert for their review and input. We are also grateful for the continuing support from our key funding partners: the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs; the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade; and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. -

Analysis of Platforms in Lebanon's 2018 Parliamentary Election

ا rلeمtركnزe اCل لبeنsانneي aلbلeدرLا eساThت LCPS for Policy Studies r e p a 9 Analysis of Platforms 1 P 0 2 y a y M in Lebanon's 2018 c i l o Parliamentary Election P Nizar Hassan Founded in 1989, the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies is a Beirut-based independent, non-partisan think tank whose mission is to produce and advocate policies that improve good governance in fields such as oil and gas, economic development, public finance, and decentralization. Copyright© 2019 The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies Designed by Polypod Executed by Dolly Harouny Sadat Tower, Tenth Floor P.O.B 55-215, Leon Street, Ras Beirut, Lebanon T: + 961 1 79 93 01 F: + 961 1 79 93 02 [email protected] www.lcps-lebanon.org Analysis of Platforms in Lebanon's 2018 Parliamentary Election 1 1 Nizar Hassan The author would like to thank Sami Nizar Hassan is a former researcher at the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies. He Atallah, John McCabe, and Georgia Dagher for their contributions to this paper. holds an M.Sc. in Labour, Social Movements and Development from the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. At LCPS, his work focused on Lebanese political parties and movements and their policy platforms. His master’s research examined protest movements in Lebanon and he currently researches political behavior in the districts of Chouf and Aley. Nizar co-hosts ‘The Lebanese Politics Podcast’, and his previous work has included news reporting and non-profit project management. 2 LCPS Policy Paper Introduction Prior to the May 2018 Lebanese Parliamentary Election, a majority of 2 2 political parties and emerging political groups launched electoral Henceforth referred to as 'emerging platforms outlining their political and socioeconomic goals and means groups'. -

Briefing Notes 19 December 2016

Group 22 – Information Centre for Asylum and Migration Briefing Notes 19 December 2016 Afghanistan Armed clashes Hostilities, raids and attacks, some involving fatalities or injuries among the civilian population, continue to occur. According to press reports, the follow- ing provinces were affected in recent weeks: Parwan, Nangarhar, Ghazni, Za- bul, Nuristan, Helmand, Balkh, Kunduz, Kabul (Paghman district). The Afghan Local Police in Kunduz (North-East Afghanistan) are demanding heavy weapons, claiming that they are otherwise unable to combat the Taliban in the province effectively. Targeted attacks On 13.12.16 a border police commander and his bodyguard were killed in a bomb attack in Kunar (East Af- ghanistan). A girl was killed in an attack by insurgents on a bus in Badakhstan (North-East Afghanistan); two people were injured. Two insurgents died in Kabul on 14.12.16 when their explosives blew up prematurely. One foreigner was shot dead by a guard near Kabul airport and at least two were injured. Two children were killed in an explosion in Zabul (South-East Afghanistan) on 15.12.16. Three children and one woman were injured. Two suicide bombers were arrested before they had an opportunity to carry out an attack in Nangarhar (South-East Afghanistan). Five female airport employees were shot dead by unknown assailants on their way to work in Kandahar (South Afghanistan) on 17.12.16. Taliban executed a mother of two in Badghis (West Afghanistan) on 19.12.16. She had married another man after her first husband went to Iran. On returning, the latter had denounced his wife to the Taliban. -

The World Factbook

The World Factbook Africa :: Mali Introduction :: Mali Background: The Sudanese Republic and Senegal became independent of France in 1960 as the Mali Federation. When Senegal withdrew after only a few months, what formerly made up the Sudanese Republic was renamed Mali. Rule by dictatorship was brought to a close in 1991 by a military coup that ushered in a period of democratic rule. President Alpha KONARE won Mali's first two democratic presidential elections in 1992 and 1997. In keeping with Mali's two-term constitutional limit, he stepped down in 2002 and was succeeded by Amadou Toumani TOURE, who was elected to a second term in 2007 elections that were widely judged to be free and fair. Malian returnees from Libya in 2011 exacerbated tensions in northern Mali, and Tuareg ethnic militias started a rebellion in January 2012. Low- and mid-level soldiers, frustrated with the poor handling of the rebellion overthrew TOURE on 22 March. Intensive mediation efforts led by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) returned power to a civilian administration in April with the appointment of interim President Dioncounda TRAORE. The post-coup chaos led to rebels expelling the Malian military from the three northern regions of the country and allowed Islamic militants to set up strongholds. Hundreds of thousands of northern Malians fled the violence to southern Mali and neighboring countries, exacerbating regional food insecurity in host communities. An international military intervention to retake the three northern regions began in January 2013 and within a month most of the north had been retaken. -

Liberalism, Marxism and Democratic Theory Revisited: Proposal of a Joint Index of Political and Economic Democracy

brazilianpoliticalsciencereview ARTICLE Liberalism, Marxism and Democratic Theory Revisited: Proposal of a Joint Index of Political and Economic Democracy Angelo Segrillo Department of History, University of São Paulo Liberalism and Marxism are two schools of thought which have left deep imprints in sociological, political and economic theory. They are usually perceived as opposite, rival approaches. In the field of democracy there is a seemingly in- surmountable rift around the question of political versus economic democracy. Liberals emphasize the former, Marxists the latter. Liberals say that economic democracy is too abstract and fuzzy a concept, therefore one should concentrate on the workings of an objective political democracy. Marxists insist that political democracy without economic democracy is insufficient. The article argues that both propositions are valid and not mutually exclu- sive. It proposes the creation of an operational, quantifiable index of economic democracy that can be used alongside the already existing indexes of political democracy. By using these two indexes jointly, political and economic democracy can be objectively evaluated. Thus, the requirements of both camps are met and maybe a more dialogical approach to democracy can be reached in the debate between liberals and Marxists. The joint index is used to evaluate the levels of economic and political democracy in the transition countries of Eastern Europe. Keywords: democratic theory; transition countries; economic democracy Introduction iberalism and Marxism are two schools of thought which have left deep imprints Lin political, sociological and economic theory. Both have been very fruitful in il- luminating a wide range of common issues across these fields and yet are usually perceived 8 bpsr Liberalism, Marxism and Democratic Theory Revisited: Proposal of a Joint Index of Political and Economic Democracy as opposite, rival approaches contradicting each other in general. -

The Long Shadow of Ordoliberalism: Germany's Approach to the Euro Crisis

brief policy The long shadow of ordoliberalism: germany’s approach To The euro crisis sebastian dullien and ulrike guérot At the end of January, European leaders agreed the wording SUMMARY The new treaty agreed by European leaders of the new treaty aimed primarily at tightening fiscal policy in in January reflects Germany’s distinctive the euro area that was agreed in principle by 26 EU heads of approach to the euro crisis rather than collective government at last December’s European summit. The treaty compromise. Much to the frustration of many reflects German positions rather than collective compromise. other eurozone countries, Germany has imposed In particular, the treaty centres on a “fiscal compact” that its own approach – centred on austerity and price stability at the expense of economic growth compels all eurozone countries to incorporate into their – on others without considering whether the constitutions a deficit limit modelled on the German institutional flaws of monetary union beyond a Schuldenbremse, or “debt brake”. In addition, European lack of fiscal control may be the cause of some leaders once again ruled out the possibility of using European of the distortions and problems that the current Central Bank (ECB) funds to “leverage” the European euro crisis has exposed or whether its approach Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) or European Stability could have a negative impact on other eurozone Mechanism (ESM), and there was no mention of ECB bond countries. German economic orthodoxy has been widely criticised elsewhere in Europe. purchases to help stabilise bond markets. This brief explores the historical and ideological However, although the new treaty reflects views that are foundations of German economic thinking supported by a broad consensus in Germany (strict opposition and discusses how it differs from mainstream to ECB intervention and a one-sided focus on fiscal austerity), international economic discourse.