Borneo Biomedical Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appell, GN 1986 Kayan Land Tenure and the Distribution of Devolvable

- 119 - Appell, G. N. 1986 Kayan Land Tenure and the Distribution of Devolvable Usufruct in Borneo. Borneo Research Bulletin 18:119-30. KAYAN LAND TENURE AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF DEVOLVABLE USUFRUCT IN BORNEO G. N. Appell Brandeis University INTRODUCTION The literature on land tenure among the indigenous peoples of Borneo perpetuates an error with regard to the Kayan system of land tenure. It is stated that among the Kayan no devolvable usufructary rights are created by the clearing of primary forest (e.g. Rousseau 1977:136) and that the Kayan land tenure system is, therefore, like that of the Rungus of Sabah. However, according to my field inquiries the Kayan and Rungus have radically different systems of land tenure. In correcting this misapprehension it will be necessary to review the status of research on land tenure in Borneo and pose critical questions for further research.1 THE TYPES OF LAND TENURE SYSTEMS IN THE SWIDDEN SOCIETIES OF BORNEO There are two basic types of land tenure systems found in those societies practicing swidden agriculture (see Appell 1971a). First, there is what I term "the circulating usufruct system"; and second, there is what I call "the devolvable usufruct system" (See Appell 1971b).2 In the system of circulating usufruct, once a swidden area has reverted to forest, any member of the village may cut the forest again to make a swidden without seeking permission of the previous cultivator. In other words, no devolvable or permanent use rights are established by cutting primary forest. Examples of this type of system may be found among the Rungus (See Appell 1971b, 1976) and the Bulusu' (see Appell 1983a, n.d.). -

Social Semiotics: Realizing Destination Image by Means of Cultural Representations

International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, Vol. 5, No. 1, January 2015 Social Semiotics: Realizing Destination Image by Means of Cultural Representations Hanita Hassan However, studies on tourism from a communication Abstract—This paper discusses the ways in which cultures perspective are lacking [7] and therefore this study aimed to are used as a part of tourism commodities to realize destination study how Malaysian diverse cultures are represented to image. Tourism advertisements were analyzed using realize a destination image using social semiotic framework. multimodal discourse framework. The findings show that both, linguistic and nonlinguistic, modes complement each other as social semiotic resources in realizing cultures as destination image. Different ethnic groups that reside in Malaysia and II. SOCIAL SEMIOTICS AS A MEANING MAKING TOOL traditional lifestyles which compose Malaysian cultures are linguistically described as to instill the sense of pleasure, A. Semiotic Resources impressiveness and recreational. On the other hand, images Social semiotics refers to social or semiotic actions that that portray Malaysian cultures, for example, people from produce meaning. The main concern of social semiotics is on different ethnicities, traditional costumes and traditional houses are found to be exclusively adopted in tourism advertisements the construction of social meaning, or a common theme, by as persuasive tools. means of semiotic forms, for instance, texts and practices [8], [9]. In order to derive to the shared meaning, the society Index Terms—Culture, meaning making. social semiotics, needs to get hold of certain semiotic resources. tourism advertisements. Semiotic resources include almost everything we do or make that contributes to meaning and this thus makes it clear that 'semiotic resources are not restricted to speech and I. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

NOVEMBER 2019 Stargazing in New Zealand

NOVEMBER 2019 Stargazing in New Zealand MY Guide to Colombo, Sri Lanka ■ Melbourne’s Chef Ang Ling Chee of Parklife Love Affair With All Things Creative ■ Traditional Pottery Making In Perak •_Nov 2019_Cover_OK.indd 2 17/10/2019 12:32 PM EXPLORE | Sarawak Litsea Scents of the Rainforest Commercialising essential oils harvested from the Sarawak rainforest to empower indigenous communities. Words Carolyn Hong | Photography courtesy of Sarawak Biodiversity Centre The sun was low in the sky and the On that trek guided by Taie and his son Ukong rainforest was growing dark as Margarita Taie, the team mapped out the indigenous goingplacesmagazine.com Naming and her team from the Sarawak plants commonly used in the villages of Long Biodiversity Centre (SBC) trudged back to the Telingan and Long Kerebangan, both located village. Suddenly, a zesty scent filled the air. over three hours’ away by road from the nearest town. Margarita remembered clambering up and To many Malaysians, a sudden sultry scent in the down muddy slopes, walking for hours to search jungle is a signal to hurry away without looking for plants used locally as medicines, food and back. But to Margarita’s team, it was cause to other purposes. “We kept asking ‘are we there stop to take a closer look – their exhaustion yet?’,” she recalled, laughing. | 48 immediately forgotten, their senses awakened | November 2019 November | and their curiosity piqued. Back in their labs in Kuching, the team set out to analyse the chemistry of the Litsea cubeba The invigorating scent, reminiscent of citronella berries and other cuttings. To their excitement, or lemongrass, was emanating from tiny they found its oil composition to be markedly 1 berry-like fruits being picked by their forest different from similar Litsea plants found in the guide and local medicinal plant expert, the late highlands of China and Taiwan, where they 1. -

Through Central Borneo

LIBRARY v.. BOOKS BY CARL LUMHOLTZ THKODOH CENTRAL BORNEO NEW TRAILS IN MEXICO AMONG CANNIBALS Ea(k Profuitly llluilraUd CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS THROUGH CENTRAL BORNEO 1. 1>V lutKSi « AKI. J-lMHol,!/. IN IMK HI 1 N<. AN U H THROUGH CENTRAL BORNEO AN ACCOUNT OF TWO YEARS' TRAVEL IN THE LAND OF THE HEAD-HUNTERS BETWEEN THE YEARS 1913 AND 1917 BY ^ i\^ ^'^'' CARL LUMHOLTZ IfEMBER OF THE SOaETY OF SCIENCES OF CHRISTIANIA, NORWAY GOLD MEDALLIST OF THE NORWEGIAN GEOGRAPHICAL SOCTETY ASSOCIE ETRANGER DE LA SOCIETE DE L'ANTHROPOLOGIE DE PARIS, ETC. WITH ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY THE AUTHOR AND WITH MAP VOLUME I NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1920 COPYKICBT, IMO. BY CHARLF.'; '^CRIBN'ER'S SONS Publubed Sepcembcr, IMU We may safely affirm that the better specimens of savages are much superior to the lower examples of civilized peoples. Alfred Russel ffallace. PREFACE Ever since my camping life with the aborigines of Queensland, many years ago, it has been my desire to explore New Guinea, the promised land of all who are fond of nature and ambitious to discover fresh secrets. In furtherance of this purpose their Majesties, the King and Queen of Norway, the Norwegian Geographical So- ciety, the Royal Geographical Society of London, and Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, generously assisted me with grants, thus facilitating my efforts to raise the necessary funds. Subscriptions were received in Norway, also from American and English friends, and after purchasing the principal part of my outfit in London, I departed for New York in the au- tumn of 1913, en route for the Dutch Indies. -

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES to the TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, the Natives

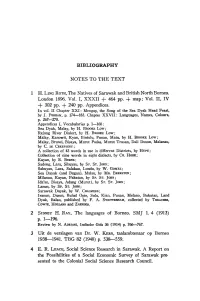

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES TO THE TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo. London 18%. Vol. I, XXXII + 464 pp. + map; Vol. II, IV + 302 pp. + 240 pp. Appendices. In vol. II Chapter XXI: Mengap, the Song of the Sea Dyak Head Feast, by J. PERHAM, p. 174-183. Chapter XXVII: Languages, Names, Colours, p.267-278. Appendices I, Vocabularies p. 1-160: Sea Dyak, Malay, by H. BROOKE Low; Rejang River Dialect, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Kanowit, Kyan, Bintulu, Punan, Matu, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Brunei, Bisaya, Murut Padas, Murut Trusan, Dali Dusun, Malanau, by C. DE CRESPIGNY; A collection of 43 words in use in different Districts, by HUPE; Collection of nine words in eight dialects, by CH. HOSE; Kayan, by R. BURNS; Sadong, Lara, Sibuyau, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sabuyau, Lara, Salakau, Lundu, by W. GoMEZ; Sea Dayak (and Bugau), Malau, by MR. BRERETON; Milanau, Kayan, Pakatan, by SP. ST. JOHN; Ida'an, Bisaya, Adang (Murut), by SP. ST. JOlIN; Lanun, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sarawak Dayak, by W. CHALMERS; Iranun, Dusun, Bulud Opie, Sulu, Kian, Punan, Melano, Bukutan, Land Dyak, Balau, published by F. A. SWETTENHAM, collected by TREACHER, COWIE, HOLLAND and ZAENDER. 2 SIDNEY H. RAY, The languages of Borneo. SMJ 1. 4 (1913) p.1-1%. Review by N. ADRIANI, Indische Gids 36 (1914) p. 766-767. 3 Uit de verslagen van Dr. W. KERN, taalambtenaar op Borneo 1938-1941. TBG 82 (1948) p. 538---559. 4 E. R. LEACH, Social Science Research in Sarawak. A Report on the Possibilities of a Social Economic Survey of Sarawak pre sented to the Colonial Social Science Research Council. -

FORUM MASYARAKAT ADAT DATARAN TINGGI BORNEO (FORMADAT) Borneo (Indonesia & Malaysia)

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. FORUM MASYARAKAT ADAT DATARAN TINGGI BORNEO (FORMADAT) Borneo (Indonesia & Malaysia) Equator Initiative Case Studies Local sustainable development solutions for people, nature, and resilient communities UNDP EQUATOR INITIATIVE CASE STUDY SERIES Local and indigenous communities across the world are 126 countries, the winners were recognized for their advancing innovative sustainable development solutions achievements at a prize ceremony held in conjunction that work for people and for nature. Few publications with the United Nations Convention on Climate Change or case studies tell the full story of how such initiatives (COP21) in Paris. Special emphasis was placed on the evolve, the breadth of their impacts, or how they change protection, restoration, and sustainable management over time. Fewer still have undertaken to tell these stories of forests; securing and protecting rights to communal with community practitioners themselves guiding the lands, territories, and natural resources; community- narrative. The Equator Initiative aims to fill that gap. based adaptation to climate change; and activism for The Equator Initiative, supported by generous funding environmental justice. The following case study is one in from the Government of Norway, awarded the Equator a growing series that describes vetted and peer-reviewed Prize 2015 to 21 outstanding local community and best practices intended to inspire the policy dialogue indigenous peoples initiatives to reduce poverty, protect needed to take local success to scale, to improve the global nature, and strengthen resilience in the face of climate knowledge base on local environment and development change. Selected from 1,461 nominations from across solutions, and to serve as models for replication. -

English for the Indigenous People of Sarawak: Focus on the Bidayuhs

CHAPTER 6 English for the Indigenous People of Sarawak: Focus on the Bidayuhs Patricia Nora Riget and Xiaomei Wang Introduction Sarawak covers a vast land area of 124,450 km2 and is the largest state in Malaysia. Despite its size, its population of 2.4 million people constitutes less than one tenth of the country’s population of 30 million people (as of 2015). In terms of its ethnic composition, besides the Malays and Chinese, there are at least 10 main indigenous groups living within the state’s border, namely the Iban, Bidayuh, Melanau, Bisaya, Kelabit, Lun Bawang, Penan, Kayan, Kenyah and Kajang, the last three being collectively known as the Orang Ulu (lit. ‘upriver people’), a term that also includes other smaller groups (Hood, 2006). The Bidayuh (formerly known as the Land Dayaks) population is 198,473 (State Planning Unit, 2010), which constitutes roughly 8% of the total popula- tion of Sarawak. The Bidayuhs form the fourth largest ethnic group after the Ibans, the Chinese and the Malays. In terms of their distribution and density, the Bidayuhs are mostly found living in the Lundu, Bau and Kuching districts (Kuching Division) and in the Serian district (Samarahan Division), situated at the western end of Sarawak (Rensch et al., 2006). However, due to the lack of employment opportunities in their native districts, many Bidayuhs, especially youths, have migrated to other parts of the state, such as Miri in the east, for job opportunities and many have moved to parts of Peninsula Malaysia, espe- cially Kuala Lumpur, to seek greener pastures. Traditionally, the Bidayuhs lived in longhouses along the hills and were involved primarily in hill paddy planting. -

Megalithic Societies of Eastern Indonesia

Mégalithismes vivants et passés : approches croisées Living and Past Megalithisms: interwoven approaches Mégalithismes vivants et passés : approches croisées Living and Past Megalithisms: interwoven approaches sous la direction de/edited by Christian Jeunesse, Pierre Le Roux et Bruno Boulestin Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 345 8 ISBN 978 1 78491 346 5 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the authors 2016 Couverture/Cover image: left, a monumental kelirieng, a carved hardwood funeral post topped by a heavy stone slab, Punan Ba group, Balui River, Sarawak (Sarawak Museum archives, ref. #ZL5); right, after Jacques Cambry, Monumens celtiques, ou recherches sur le culte des Pierres (Paris, chez madame Johanneau, libraire, 1805), pl. V. Institutions partenaires/Partner institutions : Centre national de la recherche scientifique Institut universitaire de France Université de Strasbourg Maison interuniversitaire des Sciences de l’Homme – Alsace Unité mixte de recherche 7044 « Archéologie et histoire ancienne : Méditerranée – Europe » (ARCHIMÈDE) Unité mixte de recherche 7363 « Sociétés, acteurs, gouvernements en Europe » (SAGE) Association pour la promotion de la recherche archéologique en Alsace All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Oxuniprint, Oxford -

Learn Thai Language in Malaysia

Learn thai language in malaysia Continue Learning in Japan - Shinjuku Japan Language Research Institute in Japan Briefing Workshop is back. This time we are with Shinjuku of the Japanese Language Institute (SNG) to give a briefing for our students, on learning Japanese in Japan.You will not only learn the language, but you will ... Or nearby, the Thailand- Malaysia border. Almost one million Thai Muslims live in this subregion, which is a belief, and learn how, to grow other (besides rice) crops for which there is a good market; Thai, this term literally means visitor, ASEAN identity, are we there yet? Poll by Thai Tertiary Students ' Sociolinguistic. Views on the ASEAN community. Nussara Waddsorn. The Assumption University usually introduces and offers as a mandatory optional or free optional foreign language course in the state-higher Japanese, German, Spanish and Thai languages of Malaysia. In what part students find it easy or difficult to learn, taking Mandarin READING HABITS AND ATTITUDES OF THAI L2 STUDENTS from MICHAEL JOHN STRAUSS, presented partly to meet the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS (TESOL) I was able to learn Thai with Sukothai, where you can learn a lot about the deep history of Thailand and culture. Be sure to read the guide and learn a little about the story before you go. Also consider visiting neighboring countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia. Air LANGUAGE: Thai, English, Bangkok TYPE OF GOVERNMENT: Constitutional Monarchy CURRENCY: Bath (THB) TIME ZONE: GMT No 7 Thailand invites you to escape into a world of exotic enchantment and excitement, from the Malaysian peninsula. -

Inequality of Opportunities Among Ethnic Groups in the Philippines Celia M

Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas Inequality of Opportunities Among Ethnic Groups in the Philippines Celia M. Reyes, Christian D. Mina and Ronina D. Asis DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2017-42 The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are being circulated in a limited number of copies only for purposes of soliciting comments and suggestions for further refinements. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. December 2017 For comments, suggestions or further inquiries please contact: The Research Information Department, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 18th Floor, Three Cyberpod Centris – North Tower, EDSA corner Quezon Avenue, 1100 Quezon City, Philippines Tel Nos: (63-2) 3721291 and 3721292; E-mail: [email protected] Or visit our website at https://www.pids.gov.ph Inequality of opportunities among ethnic groups in the Philippines Celia M. Reyes, Christian D. Mina and Ronina D. Asis. Abstract This paper contributes to the scant body of literature on inequalities among and within ethnic groups in the Philippines by examining both the vertical and horizontal measures in terms of opportunities in accessing basic services such as education, electricity, safe water, and sanitation. The study also provides a glimpse of the patterns of inequality in Mindanao. The results show that there are significant inequalities in opportunities in accessing basic services within and among ethnic groups in the Philippines. -

The Forests Dialogue Food, Fuel, Fiber and Forests (4Fs) Indonesia Field Dialogue Central Kalimantan, Indonesia | 16-19 March 2014

The Forests Dialogue Food, Fuel, Fiber and Forests (4Fs) Indonesia Field Dialogue Central Kalimantan, Indonesia | 16-19 March 2014 FIELD TRIP SITE INFORMATION Map of the locations Community forest in Buntoi Tenure (Who owns the land? Who manage the land?) The community considers that they own the land. Part of the land is privately owned, viz. rubber and fruit gardens and areas for rice cultivation. Forest is communally owned. However the community has no official documents to prove their rights. Only recently did they receive a permit from the Ministry of Forestry to manage the community forest. The government considers all land state land and the government has the right to issue certificates (for ownership) or licenses to third parties to manage a certain area. Land use history Until 1970s only community land use, mainly for subsistence and some extraction of valuable products demanded by the market. In 1970 timber concessions were allocated by the national government. The timber companies exploited a limited number of commercial timber species. Communities were still able to partly use their village territory. In 1990s oil palm plantations were developed in Central Kalimantan. Initially government would allocate area to oil palm plantation, often with limited (or no) scheme for smallholders. In general this created problems because communities lost large tracks of their community land. With political reforms, and increased protest by communities the government changed the regulation for oil palm plantation requiring oil palm plantations to allocate 20% of the area to smallholder schemes. Buntoi has no established oil palm plantations in its village territory, but has had oil palm concession allocated to its village territory.