Waymarking Italy's Influence on the American Environmental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincia Di Perugia [email protected] Provincia Di Terni [email protected] Comune Di Acqu

Provincia di Perugia [email protected] Documento elettronico sottoscritto Provincia di Terni mediante firma digitale e conservato nel sistema di protocollo informatico [email protected] della Regione Umbria Comune di Acquasparta [email protected] Comune di Allerona [email protected] GIUNTA REGIONALE Direzione Regionale Comune di Alviano Programmazione Innovazione e [email protected] Competitività dell'Umbria Comune di Amelia [email protected] Servizio Urbanistica Centri Storici e Espropriazioni Comune di Arrone [email protected] Dirigente Angelo Pistelli Comune di Assisi [email protected] REGIONE UMBRIA Via Mario Angeloni, 61 06124 Perugia Comune di Attigliano TEL. 075 504 5962 [email protected] FAX 075 5045567 [email protected] Indirizzo PEC Comune di Avigliano Umbro areaprogrammazione.regione@postacert. [email protected] umbria.it Comune di Baschi [email protected] Comune di Bastia Umbra [email protected] Comune di Bettona [email protected] Comune di Bevagna [email protected] Comune di Calvi [email protected] Comune di Campello sul Clitunno www.regione.umbria.it WWW.REGIONE .UMBRIA.IT [email protected] Comune di Cannara [email protected] Comune di Cascia [email protected] Comune di Castel -

The Saint Francis'

Gubbio - Biscina Valfabbrica - Ripa Assisi - Foligno Spoleto - Ceselli The Reatine Valley (Lazio) LA VERNA Planning a Distance: 22,8 km Distance: 10,5 km Distance: 21,8 km Distance: 15,9 km The Sacred Valley of Rieti is full of testimony PIEVE S. STEFANO Height difference: + 520 / - 500 m Height difference: + 90 / - 50 m Height difference: + 690 / - 885 m Height difference: + 490 / - 680 m to St. Francis. The Greccio Hermitage, the Difficulty: challenging Difficulty: easy Difficulty: Challenging Difficulty: Challenging Sanctuaries of Fontecolombo and La Foresta, your CERBAIOLO VIA DI FRANCESCO the temple of Terminillo and the Beech Tree b SAINT FRANCIS - AND THE WOLF OF Val fabbrica (Pg) SAINT FRANCIS - IN FOLIGNO SAINT FRANCIS - IN SPOLETO of St. Francis are just some of the best-known GUBBIO Francis therefore leapt to his feet, made the Nil iucundius vidi valle mea spoletana landmarks. If you would like to see these Trip The sermon being ended, Saint Francis added Franciscan itinerary: sign of the cross, prepared a horse, got into the I have never seen anything more joyful than places, a visit to the website of the these words: Church of Coccorano saddle, and taking scarlet cloth with him set off my Spoleto valley - Saint Francis’ Rieti tourist board is highly recommended, “Listen my brethren: the wolf who is here before 13 Church of Santa Maria Assunta at speed for Foligno. There, as was his custom, at www.camminodifrancesco.it. c you has promised and pledged his faith that he sold all his goods and with a stroke of luck he consents to make peace with you all, and sold his horse as well. -

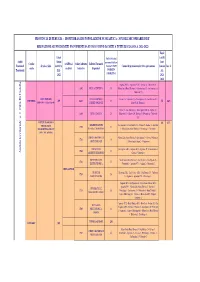

REPORT STUDENTI ISCRITTI DA COMUNI DIVERSI A.S 2021-2022.Pdf

PROVINCIA DI PERUGIA - MONITORAGGIO POPOLAZIONE SCOLASTICA - SCUOLE SECONDARIE DI II° RILEVAZIONE ALUNNI ISCRITTI PROVENIENTI DA FUORI COMUNE (ISCRITTI A TUTTE LE CLASSI A.S. 2021-2022) Totale Totale TOTALE Iscritti iscritti Ambiti Alunni fuori Ccodice Sedi/Plessi Codice indirizzo Indirizzi Formativi provenienti da fuori Funzionali Scuola e Sede iscritti AS Comune X OGNI Comuni di provenienza/iscritti x ogni comune Comune Inc. % scuola scoalstici formativo frequentati Territoriali 2021- INDIRIZZO A.S. 2022 FORMATIVO 2021- 2022 Anghiari AR (1) - Apecchio PU (2) - Citerna (3) - Monterchi (2) - LI02 LICEO SCIENTIFICO 23 Monta Santa Maria Tiberina (3) - San Giustino (7) - San Sepolcro (2)- Umbertide (3) LICEO "PLINIO IL LICEO SCIENTIFICO Citerna (1) - Umbertide (13) - San Sepolcro (1) - San Giustino (2) - PGPC05000A 499 L103 19 71 14% GIOVANE" - Città di Castello SCIENZE APPLICATE Monte S. M. Tiberina (2) Citerna (3) - San Giustino (4) - San Sepolcro AR (4)- Anghiari (1) - LI01 LICEO CLASSICO 29 Monterchi (1) - Monte S.M. Tiberina (1) - Perugia (2) - Umbertide (13) ISTITUTO ECONOMICO 425 45% AMMINISTRAZIONE San Giustino 11 - San Sepolcro 11 - Citerna 6 - Anghiari 2 - Apecchio TECNOLOGICO IT01 41 "FRANCHETTI-SALVIANI" FINANZA E MARKETING 1 - Monte Santa Maria Tiberina 5 - Pietralunga 1 -Umbertide 4 CITTA' DI CASTELLO CHIMICA MATERIALI E Monte Santa Maria Tiberina 2 - San Giustino 2 - Citerna 2 -Monterchi IT16 10 BIOTECNOLOGIE 1 - Pieve Santo Stefano 2 - Verghereto 1 COSTRUZIONI San Sepolcro AR 1- Anghiari AR 2 - Apecchio PU 2- San Giustino -

Rankings Municipality of Citerna

9/29/2021 Maps, analysis and statistics about the resident population Demographic balance, population and familiy trends, age classes and average age, civil status and foreigners Skip Navigation Links ITALIA / Umbria / Province of Perugia / Citerna Powered by Page 1 L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH ITALIA Municipalities Powered by Page 2 Assisi Stroll up beside >> L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Giano AdminstatBastia Umbra logo dell'Umbria DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH Bettona ITALIA Gualdo Bevagna Cattaneo Campello sul Gualdo Tadino Clitunno Gubbio Cannara Lisciano Cascia Niccone Castel Ritaldi Magione Castiglione del Marsciano Lago Massa Martana Cerreto di Monte Castello Spoleto di Vibio Citerna Monte Santa Città della Maria Tiberina Pieve Montefalco Città di Castello Monteleone di Collazzone Spoleto Corciano Montone Costacciaro Nocera Umbra Deruta Norcia Foligno Paciano Fossato di Vico Panicale Fratta Todina Passignano sul Trasimeno Perugia Piegaro Pietralunga Poggiodomo Preci San Giustino Sant'Anatolia di Narco Scheggia e Pascelupo Scheggino Sellano Powered by Page 3 Sigillo L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Provinces Spello Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH Spoleto PERUGIAITALIA Todi TERNI Torgiano Trevi Tuoro sul Trasimeno Umbertide Valfabbrica Vallo di Nera Valtopina Regions Abruzzo Liguria Basilicata Lombardia Calabria Marche Campania Molise Città del Piemonte Vaticano Puglia Emilia-Romagna Repubblica di Friuli-Venezia -

Località Disagiate Umbria

Località disagiate Umbria Tipo Regione Prov. Comune Frazione Cap gg. previsti Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA ATRI 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA AVENDITA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA BUDA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA CAPANNE DI ROCCA PORENA 6043 4 Comune DisagiataUmbria PG CASCIA CASCIA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA CASCINE DI OPAGNA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA CASTEL SAN GIOVANNI 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA CASTEL SANTA MARIA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA CERASOLA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA CHIAVANO 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA CIVITA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA COLFORCELLA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA COLLE DI AVENDITA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA COLLE GIACONE 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA COLMOTINO 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA CORONELLA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA FOGLIANO 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA FUSTAGNA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA GIAPPIEDI 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA LOGNA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA MALTIGNANO 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA MALTIGNANO DI CASCIA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA MANIGI 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA OCOSCE 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA ONELLI 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA OPAGNA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA PALMAIOLO 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA PIANDOLI 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA POGGIO PRIMOCASO 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA PURO 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA ROCCA PORENA 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA SAN GIORGIO 6043 4 Disagiata Umbria PG CASCIA SANT'ANATOLIA -

I Borghi Più Belli D'italia

I Borghi più Belli d’Italia Il fascino dell’Italia nascosta UUmmbbrriiaa MAGICAL VILLAGE ENERGIZE FOR LIFE Tour of the villages and festivals Fireworks, Folklore, Art, Music and Fine Tasting I BORGHI PIÙ BELLI D’ITALIA is an BORGHI ITALIA TOUR NETWORK is the exclusive club that contains the Citerna exclusive TOUR OPERATOR of the Club of most beautiful villages of Italy. This Montone the Most Beautiful Villages of Italy - Anci Castiglione Corciano initiative arose from the need to del Lago S. Antonio and responsible of tourism activity and Torgiano Bettona Paciano Panicale Spello promote the great heritage of His - Deruta strategy. It turns the hudge Heritage of Monte Castello Bevagna di Vibio tory, Art, Culture, Environment and Montefalco Trevi art, culture, traditions, fine food and wine Traditions of small Italian towns Massa Martana Norcia and the beauties of natural environment Acquasparta Vallo di Nera which are, for the large part, ex - in a unique Italian tourist product, full of Lugnano San Gemini Arrone cluded from the flows of visitors in Teverina charm and rich in contents. Emotional and tourists. Giove Stroncone tourism and relationship tourism. UMBRIA, near Rome and Florence, is the region with the largest number of most beautiful villages of Italy: 24! It’s land of grapes and olives, that pro - duces, from ancient Roman times, fine wine and oil; it’s land of mystical abbeys: between St. Benedict, patron of Europe and St. Francis, patron of Italy. Umbria is land of peace. THE BORGO… The most beautiful “borghi” of Italy are enchanted places whose beauty, consolidated over the centuries, tran - scends our lives, whose squares, fortresses, castles, churches, palaces, towers, bell towers, landscapes, festivals, typical products, stories allows us to understand what really Italy is, beyond the rhetoric, the most beautiful country in the world. -

Comune Di Bastia Umbra Nota Di Aggiornamento Al Documento Unico Di Programmazione (D.U.P.) 2017-2019 Approvato Con Delibera C.C

COMUNE DI BASTIA UMBRA NOTA DI AGGIORNAMENTO AL DOCUMENTO UNICO DI PROGRAMMAZIONE (D.U.P.) 2017-2019 APPROVATO CON DELIBERA C.C. N. 66 del 06/10/2016 1 INDICE Pag. Premessa 3 Il Documento unico di programmazione degli enti locali (DUP) 4 1 La Sezione Strategica 5 2 Le linee programmatiche di mandato 7 3 Analisi del contesto esterno ed interno 51 3.1 Analisi delle condizioni esterne 52 3.1.1 Compatibilità presente e futura con le disposizioni e con gli obiettivi di 52 finanza pubblica - Quadro normativo di riferimento 3.1.2 Dal patto di stabilità interno al pareggio di bilancio 52 3.2 Analisi di contesto interno 56 3.2.1 Caratteristiche della popolazione e del territorio 57 3.2.2 Economia insediata 60 3.2.3 Il territorio 62 3.2.4 La struttura organizzativa 66 3.2.5 Le strutture operative 69 3.3 Organizzazione e modalità di gestione dei servizi pubblici locali 71 3.3.1 Accordi di programma 80 3.3.2 Servizi gestiti in concessione ed Altro 80 4 Gli investimenti e la realizzazione delle opere pubbliche. 80 5 La Ripartizione delle linee programmatiche di mandato, declinate in in 86 programmi e progetti, in coerenza con la nuova struttura del bilancio armonizzato ai sensi del d. lgs. 118/2011. 6 La Sezione Operativa- Parte 1^ 108 6.1 Quadro generale riassuntivo 2017-2018-2019 110 6.2 Gli equilibri di Bilancio 2017-2018-2019 111 6.3 Analisi delle risorse finanziarie 113 6.3.1 Entrate tributarie. 113 6.3.2 Contributi e trasferimenti di parte corrente. -

Loc2001 Comune Centro Abitato Popolazione 2001

LOC2001 COMUNE CENTRO ABITATO POPOLAZIONE 2001 5400110008 Assisi Pianello 92 5400110013 Assisi Torchiagina 601 5400110012 Assisi Sterpeto 45 5400110007 Assisi Petrignano 2536 5400110006 Assisi Palazzo 1343 5400110015 Assisi Tordibetto 235 5400110002 Assisi Assisi 3920 5400110001 Assisi Armenzano 40 5400110010 Assisi Santa Maria degli Angeli 6665 5400110009 Assisi Rivotorto 1284 5400110011 Assisi San Vitale 494 5400110014 Assisi Tordandrea 898 5400110005 Assisi Castelnuovo 754 5400110003 Assisi Capodacqua 92 5400110004 Assisi Case Nuove 312 5400210001 Bastia Umbra Bastia 15090 5400210003 Bastia Umbra Ospedalicchio 1139 5400210002 Bastia Umbra Costano 782 5400310003 Bettona Passaggio 896 5400310002 Bettona Colle 114 5400310001 Bettona Bettona 590 5400410004 Bevagna Limigiano 56 5400410002 Bevagna Cantalupo 332 5400410001 Bevagna Bevagna 2559 5400410005 Bevagna Torre del Colle 33 5400410003 Bevagna Gaglioli 28 5400510002 Campello sul Clitunno Pettino 74 5400510001 Campello sul Clitunno Campello sul Clitunno 1889 5400610001 Cannara Cannara 2508 5400610002 Cannara Collemancio 78 5400710001 Cascia Avendita 138 5400710016 Cascia San Giorgio 69 5400710011 Cascia Poggio Primocaso 74 5400710007 Cascia Logna 65 5400710006 Cascia Fogliano 119 5400710005 Cascia Colle Giacone 72 5400710015 Cascia Padule 45 5400710002 Cascia Cascia 1515 5400710009 Cascia Ocosce 93 5400710012 Cascia Rocca Porena 73 5400710008 Cascia Maltignano 130 5400710010 Cascia Onelli 51 5400710004 Cascia Civita 58 5400710003 Cascia Chiavano 38 5400710014 Cascia Villa San Silvestro -

The Risk of Wolf Attacks in Umbria's Municipalities Has Been

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Portsmouth University Research Portal (Pure) Highlights - The risk of wolf attacks in Umbria’s municipalities has been assessed. - The risk map constructed shows that a high number of municipalities are at high risk. - AHPSort II, a new risk classification sorting method based on AHP, has been developed. - It requires far fewer pairwise comparisons than its predecessor, AHPSort. 1 Sorting municipalities in Umbria according to the risk of wolf attacks with AHPSort II Francesco Miccoli, Alessio Ishizaka University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth Business School, Centre for Operational Research and Logistics, Richmond Building, Portland Street, Portsmouth PO1 3DE, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT In Italy, the recent wolf expansion process is the result of a series of historical, natural, ecological and conservation related factors that have characterized the Italian environmental context during the last few decades. The difficulties in broaching the environmental management of the wolf species have increased economic conflicts, mainly with livestock farmers. To facilitate and pacify the debate, an assessment of the risk of wolf attacks on livestock farms in Umbria’s municipalities needed to be carried out. For this assessment, AHPSort II, a new multi-criteria sorting method for a large number of alternatives, has been developed. This is used for sorting the alternatives into predefined, ordered risk categories. It requires far fewer comparisons than its predecessor, AHPSort. This sorting method can be applied to different environmental problems that have a large number of alternatives. -

Programma 8 Marzo 2014.Indd

1 2 PERUGIA martedì 4 marzo ore 10.00 Palazzo della Provincia, Sala Consiliare, Piazza Italia, 11 L’etica della pubblicità Incontro con Alessandro M. Sciortino, direttore creativo di McCann Erickson Roma Intervengono Donatella Porzi, Assessore Pari Opportunità della Provincia di Perugia Gemma Paola Bracco, Consigliera di Parità della Provincia di Perugia Coordina Maddalena Santeroni, Presidente Associazione Amici dell’Arte Moderna a Valle Giulia di Roma Parteciperanno all’incontro i ragazzi di alcune Scuole Superiori di Perugia a cura di: Assessorato Attività culturali e sociali, Politiche giovanili, Pubblica istru- zione e Pari Opportunità della Provincia di Perugia e della Consigliera di Parità della Provincia di Perugia, nell’ambito del Progetto “Lo Stato siamo noi. Leg@ lmente – Punti fermi sulla strada della nostra responsabilità” - Ingresso libero Giornale istituzionale a cura dell’Assessorato Pari Opportunità della Provincia di Perugia on line sul sito www.provincia.perugia.it e sulle principali testate on line locali giovedì 6 marzo ore 17.30 Palazzo dei Priori, Sala dei Notari Presentazione apertura Centro Antiviolenza “Catia Doriana Bellini” di Perugia Intervengono Laura Boldrini, Presidente della Camera dei Deputati Catiuscia Marini, Presidente Regione Umbria Wladimiro Boccali, Sindaco del Comune di Perugia Lorena Pesaresi, Assessore alle Pari Opportunità del Comune di Perugia Emanuela Moroli, Presidente Associazione Differenza Donna Paola Moriconi, Presidente Associazione Libera...mente Donna a cura di: Comune di Perugia, Assessorato -

Allegato N°6: Ricognizione Delle Ville E Dimore Storiche Presenti Nel PUT E Delle Ville Che Costituiscono La “La Rete Regionale Ville Parchi E Giardini”

Allegato n°6: Ricognizione delle Ville e dimore storiche presenti nel PUT e delle Ville che costituiscono la “La rete regionale Ville parchi e giardini” COMUNE LOCALITÀ DENOMINAZIONE CITERNA (loc. Petriolo) VILLA BRIGLIANA (o Brighigna) CITERNA Tra Fighille e Villa Schifanoia Schifanoia CITERNA presso Citerna Zoccolanti CITERNA presso Citerna Villa Fano CITERNA (loc. Pistrino di VILLA DURANTI Sotto) CITERNA presso Citerna I CAPPUCCINI SAN GIUSTINO S.GIUSTINO CASTELLO BUFALINI SAN GIUSTINO (loc. Celalba) VILLA IL PALAZZO SAN GIUSTINO (tra S.Giustino e VILLA MURCE (Le Murce) Selci Stazio SAN GIUSTINO (loc. Colle Plinio) VILLA CAPPELLETTI (Colle Plinio) SAN GIUSTINO (tra S.Giustino e VILLA S.MARTINO Selci stazio SAN GIUSTINO (loc. Cospaia) VILLA GIOVAGNOLI SAN GIUSTINO (tra Cospaia e S. CASA MORI (VILLA MORI) Giustino) SAN GIUSTINO (presso S. Giustino) GABRIELLONA SAN GIUSTINO (loc. Montione) CASA OTTAVIANI (Le Ville) SAN GIUSTINO (tra S.Giustino e CASA BASTIANELLI Stazione Sel SAN GIUSTINO (loc. Capanne) VILLA DELLE CAPANNE SAN GIUSTINO (loc. Capanne) CA' SAN MARCO (Marco I e II) SAN GIUSTINO (loc. Pitigliano) CASA MATRA SAN GIUSTINO (loc. Fondaccio) VILLA IN LOC. FONDACCIOI (Biccio I) MONTONE presso Montone Palazzo del Colle UMBERTIDE (tra Monte Castelli e VILLA BERTANZI Nestore) UMBERTIDE (loc. Poggio VILLA LANDUCCI Mappino) UMBERTIDE (tra Niccone e MONTALTO Umbertide) UMBERTIDE (tra Campo SERRA PARTUCCI Reggiano e C. Ranie UMBERTIDE (tra S.Benedetto e VILLA PACE Umbertide) UMBERTIDE (loc. Civitella CIVITELLA RANIERI Ranieri) UMBERTIDE (presso Umbertide) PALAZZETTO UMBERTIDE (presso Umbertide) PALAZZO S. FEDE UMBERTIDE (presso Umbertide) VILLA CORRADINO UMBERTIDE (tra Umbertide e LA VILLA (Polgeto) Preggio) UMBERTIDE (loc. Poggio POGGIO MANENTE Manente) UMBERTIDE (loc. -

Regione Umbria MINIERE Servizio Qualità Dell'ambiente: Gestione Citta' Di Castello Rifiuti E Attività Estrattive Lippiano Miniere Anno: 2010 PIETRALUNGA

2.278.895 2.293.895 2.308.895 2.323.895 2.338.895 2.353.895 12°0'E 12°10'E 12°20'E 12°30'E 12°40'E 12°50'E 13°0'E CARTA DEI DETRATTORI AMBIENTALI ARTIFICIALI Legge regionale 18.11.2008 n.° 17 articolo 7 N ' 0 4 ° 3 4 SAN GIUSTINO SORGENTI DI RADIAZIONE ELETTROMAGNETICA 5 5 Fonte: Arpa Umbria 9 9 Siti attivi 9 9 Catasto NIR - Radiazioni Non Ionizzanti e . 5 5 RF - Radio Frequenza 2 2 8 San Giustino 8 . (stazioni radiotelevisive, stazioni radiobase 4 Sant'Anastasio 4 per la telefonia mobile) Anno: 2010 Celalba Bagnaia Fonte: Arpa Umbria STAZIONI ECOLOGICHE Catasto dei rifiuti Fighille Anno: 2008 Selci-Lama Stazioni ecologiche N ' 0 3 Pistrino ° CITERNA 3 4 Citerna Cerbara Fraccano Badiali DISCARICHE Fonte: Arpa Umbria Anno: 2010 Piosina Discariche N Titta ' 0 3 ° 3 4 Lerchi Belvedere Fonte: Regione Umbria MINIERE Servizio Qualità dell'ambiente: gestione Citta' di Castello rifiuti e attività estrattive Lippiano Miniere Anno: 2010 PIETRALUNGA CITTA' DI CASTELLO Fonte: Regione Umbria Monte Santa Maria Tiberina CAVE ATTIVE Servizio Qualità dell'ambiente: gestione Pietralunga rifiuti e attività estrattive MONTE SANTA MARIA TIBERINA Altri materiali Anno: 2010 5 5 9 Isola Fossara 9 9 9 Arenarie e calcareniti . 0 Marcignano Santa Lucia 0 1 1 8 8 . Gioiello . Argille 4 4 SCHEGGIA E PASCELUPO Basalti San Secondo Croce di Castiglione Ponte Calcara Calcare Scheggia San Maiano Ghiaie e sabbie Perticano Morra Pascelupo Fabbri Badia Petroia Carpini Costa San Savino Fabrecce Cinquemiglia Bivio Lugnano Mocaiana Fonte: Regione Umbria Cornetto Monteleto Belvedere