The Prize of Governance. How the European Union Uses Symbolic Distinctions to Mobilize Society and Foster Competitiveness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Films

FEATURE FILMS NEW BERLINALE 2016 GENERATION CANNES 2016 OFFICIAL SELECTION MISS IMPOSSIBLE SPECIAL MENTION CHOUF by Karim Dridi SPECIAL SCREENING by Emilie Deleuze TIFF KIDS 2016 With: Sofian Khammes, Foued Nabba, Oussama Abdul Aal With: Léna Magnien, Patricia Mazuy, Philippe Duquesne, Catherine Hiegel, Alex Lutz Chouf: It means “look” in Arabic but it is also the name of the watchmen in the drug cartels of Marseille. Sofiane is 20. A brilliant Some would say Aurore lives a boring life. But when you are a 13 year- student, he comes back to spend his holiday in the Marseille ghetto old girl, and just like her have an uncompromising way of looking where he was born. His brother, a dealer, gets shot before his eyes. at boys, school, family or friends, life takes on the appearance of a Sofiane gives up on his studies and gets involved in the drug network, merry psychodrama. Especially with a new French teacher, the threat ready to avenge him. He quickly rises to the top and becomes the of being sent to boarding school, repeatedly falling in love and the boss’s right hand. Trapped by the system, Sofiane is dragged into a crazy idea of going on stage with a band... spiral of violence... AGAT FILMS & CIE / FRANCE / 90’ / HD / 2016 TESSALIT PRODUCTIONS - MIRAK FILMS / FRANCE / 106’ / HD / 2016 VENICE FILM FESTIVAL 2016 - LOCARNO 2016 HOME by Fien Troch ORIZZONTI - BEST DIRECTOR AWARD THE FALSE SECRETS OFFICIAL SELECTION TIFF PLATFORM 2016 by Luc Bondy With: Sebastian Van Dun, Mistral Guidotti, Loic Batog, Lena Sukjkerbuijk, Karlijn Sileghem With: Isabelle Huppert, Louis Garrel, Bulle Ogier, Yves Jacques Dorante, a penniless young man, takes on the position of steward at 17-year-old Kevin, sentenced for violent behavior, is just let out the house of Araminte, an attractive widow whom he secretly loves. -

Cultural Heritage

N°62/March 2018 EPFMA BULLETIN European Parliament Former Members Association www.formermembers.eu Cultural Heritage FMA Activities FMA Activities EP to Campus Co-operation with Programme the EUI Page 22 Page 28 2 FMA BULLETIN - 62 IN THIS ISSUE 03 Message from the President FOCUS LATEST NEWS 04 EP at work 14 European culture 31 New members viewed through the ages CURRENT AFFAIRS (Pedro Canavarro) 32 Activities In memoriam 05 1948: Start of the 15 The economic value of 33 European Constitutional Cycle cultural heritage (Manuel Porto) (Andrea Manzella) 16 The humble rural architecture 06 Democratic conventions´ of Greece (Nikolaos Sifounakis) (Nicole Fontaine) 17 Unesco (Brigitte Langenhagen) 07 United in diversity 18 Cultural property in the event (Jean-Marie Beaupuy) of armed conflict (Monica Baldi) 08 The point of view of a Former 19 Lux Film Prize (Doris Pack) Member (Ursula Braun-Moser) 09 Every five minutes... (Karin Junker) FMA ACTIVITIES A ceremony took place on 24 January 2018 at the European 10 AMAR Programme 21 Democracy Support Parliament to mark the upcoming (Emma Baroness Nicholson of International Holocaust Winterbourne) 22 EP to Campus Programme Remembrance Day on 27 January 11 Observation mission in 28 Co-operation with the EUI in memory of the victims of the Holocaust. Catalonia (Jan Dhaene) 30 FMA Annual Seminar 12 The French Federation of Cover:©iStock Houses of Europe (Martine Buron) CALL FOR CONTRIBUTIONS: The Editorial Board would like to thank all those members who took the time to contribute to this issue of the FMA Bulletin. We would like to draw your attention to the fact that the decision to include an article lies with the FMA Editorial Board and, in principle, contributions from members who are not up-to-date with the payment of the membership fee will not be included. -

Network Review #37 Cannes 2021

Network Review #37 Cannes 2021 Statistical Yearbook 2020 Cinema Reopening in Europe Europa Cinemas Network Review President: Nico Simon. General Director: Claude-Eric Poiroux Head of International Relations—Network Review. Editor: Fatima Djoumer [email protected]. Press: Charles McDonald [email protected]. Deputy Editors: Nicolas Edmery, Sonia Ragone. Contributors to this Issue: Pavel Sladky, Melanie Goodfellow, Birgit Heidsiek, Ste- fano Radice, Gunnar Rehlin, Anna Tatarska, Elisabet Cabeza, Kaleem Aftab, Jesus Silva Vilas. English Proofreader: Tara Judah. Translation: Cinescript. Graphic Design: Change is good, Paris. Print: Intelligence Publishing. Cover: Bergman Island by Mia Hansen-Løve © DR CG Cinéma-Les Films du Losange. Founded in 1992, Europa Cinemas is the first international film theatre network for the circulation of European films. Europa Cinemas 54 rue Beaubourg 75003 Paris, France T + 33 1 42 71 53 70 [email protected] The French version of the Network Review is available online at https://www.europa-cinemas.org/publications 2 Contents 4 Editorial by Claude-Eric Poiroux 6 Interview with Lucia Recalde 8 2020: Films, Facts & Figures 10 Top 50 30 European movies by admissions Czech Republic in the Europa Cinemas Network Czech exhibitors try to keep positive attitude while cinemas reopen 12 Country Focus 2020 32 France 30 French Resistance Cinema Reopening in Europe 34 46 Germany The 27 Times Cinema initiative Cinema is going to have a triumphant return and the LUX Audience Award 36 Italy Reopening -

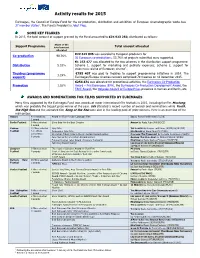

Activity Results for 2015

Activity results for 2015 Eurimages, the Council of Europe Fund for the co-production, distribution and exhibition of European cinematographic works has 37 member states1. The Fund’s President is Jobst Plog. SOME KEY FIGURES In 2015, the total amount of support granted by the Fund amounted to €24 923 250, distributed as follows: Share of the Support Programme total amount Total amount allocated allocated €22 619 895 was awarded to European producers for Co-production 90.76% 92 European co-productions. 55.76% of projects submitted were supported. €1 253 477 was allocated to the two schemes in the distribution support programme: Distribution 5.03% Scheme 1, support for marketing and publicity expenses; Scheme 2, support for awareness raising of European cinema2. Theatres (programme €795 407 was paid to theatres to support programming initiatives in 2014. The 3.19% support) Eurimages/Europa Cinemas network comprised 70 theatres on 31 December 2015. €254 471 was allocated for promotional activities, the Eurimages Co-Production Promotion 1.02% Award – Prix Eurimages (EFA), the Eurimages Co-Production Development Award, the FACE Award, the Odyssée-Council of Europe Prize, presence in Cannes and Berlin, etc. AWARDS AND NOMINATIONS FOR FILMS SUPPORTED BY EURIMAGES Many films supported by the Eurimages Fund won awards at major international film festivals in 2015, including the film Mustang, which was probably the biggest prize-winner of the year. Ida attracted a record number of awards and nominations while Youth, the High Sun and the animated film Song of the Sea were also in the leading pack of prize-winners. -

| | Film Schedule 01-31.10.2020 В И Г О П Р Е Т С Т А В У В А

В И Г О П Р Е Т С Т А В У В А РАСПОРЕД НА ФИЛМОВИ | | FILM SCHEDULE 01-31.10.2020 В И Г О П Р Е Т С Т А В У В А РАСПОРЕД НА ЕМИТУВАЊЕ НА ФИЛМОВИ | TV SCHEDULE 01-31.10.2020 01.10.2020 (четврток) 21:00 ч. | КинеНова Ретро | KineNova Retro СЛАВА од Петар Валчанов и Кристина Грозева | GLORY by Petar Valchanov and Kristina Grozeva [2016] Бугарија / Bulgaria — 01 ч. 41 мин. — премиера 02.10.2020 (петок) 21:00 ч. | КинеНова Ретро | KineNova Retro АЛЕКСИ од Барбара Векариќ | ALEKSI by Barbara Vekaric [2018] Хрватска / Croatia — 01 ч. 30 мин. — премиера 03.10.2020 (сабота) 21:00 ч. | КинеНова Ретро | KineNova Retro БЕЗ ДАТУМ, БЕЗ ПОТПИС од Вахид Јалилванд | NO DATE, NO SIGNATURE by Vahid Jalilvand [2018] Иран / Iran — 01 ч. 39 мин. — премиера 04.10.2020 (недела) 21:00 ч. | КинеНова Ретро | KineNova Retro РЕТАБЛО од Алваро Делгадо Апаричио | RETABLO by Alvaro Delgado Aparicio [2017] Перу / Peru — 01 ч. 35 мин. — премиера 05.10.2020 (понеделник) 21:00 ч. | КинеНова Ретро | KineNova Retro ПАТОТ ДО ЛА ПАЗ од Франциско Вароне | ROAD TO LA PAZ by Francisco Varone [2015] Аргентина / Argentina — 01 ч. 32 мин. — премиера В И Г О П Р Е Т С Т А В У В А РАСПОРЕД НА ЕМИТУВАЊЕ НА ФИЛМОВИ | TV SCHEDULE 01-31.10.2020 06.10.2020 (вторник) 21:00 ч. | КинеНова Ретро | KineNova Retro ПРАСЕТО од Драгомир Шолев | PIG by Dragomir Sholev [2019] Бугарија / Bulgaria — 01 ч. 36 мин. — премиера 07.10.2020 (среда) 21:00 ч. -

Copyright by Berna Gueneli 2011

Copyright by Berna Gueneli 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Berna Gueneli Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: CHALLENGING EUROPEAN BORDERS: FATIH AKIN’S FILMIC VISIONS OF EUROPE Committee: Sabine Hake, Supervisor Katherine Arens Philip Broadbent Hans-Bernhard Moeller Pascale Bos Jennifer Fuller CHALLENGING EUROPEAN BORDERS: FATIH AKIN’S FILMIC VISIONS OF EUROPE by Berna Gueneli, B.A., M.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication For my parents Mustafa and Günay Güneli and my siblings Ali and Nur. Acknowledgements Scholarly work in general and the writing of a dissertation in particular can be an extremely solitary endeavor, yet, this dissertation could not have been written without the endless support of the many wonderful people I was fortunate to have in my surroundings. First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation advisor Sabine Hake. This project could not have been realized without the wisdom, patience, support, and encouragement I received from her, or without the intellectual exchanges we have had throughout my graduate student life in general and during the dissertation writing process in particular. Furthermore, I would like to thank Philip Broadbent for discussing ideas for this project with me. I am grateful to him and to all my committee members for their thorough comments and helpful feedback. I would also like to extend my thanks to my many academic mentors here at the University of Texas who have continuously guided me throughout my intellectual journey in graduate school through inspiring scholarly questions, discussing ideas, and encouraging my intellectual quest within the field of Germanic and Media Studies. -

Report on Events Organised by the European Parliament Information Offices on the Occasion of the 2016 Sakharov Prize

EP Information Offices | Annual Report 2016 ReportReport onon eventsevents organisedorganised byby thethe EuropeanEuropean ParliamentParliament InformationInformation OfficesOffices onon thethe occasionoccasion ofof thethe 20162016 LUXSakharov Film Prize Prize Directorate for Information Offices Produced by Horizontal and Thematic Monitoring Unit Directorate for Information Offices Manuscript completed in March 2017 © European Union, 2017 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Report on events organised by the European Parliament Information Offices on the occasion of the 2016 Sakharov Prize TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 7 2 TYPES OF EVENTS 8 3 PARTICIPANTS 14 4 MEDIA AND SOCIAL MEDIA 15 5 FACTS & FIGURES 16 6 ANNEXES 17 EP Information Offices | Sakharov Prize Report 2016 1 INTRODUCTION The Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, awarded each year by the Eu- ropean Parliament, is intended to honour exceptional individuals who combat intolerance, fanaticism and oppression around the world. In 2016, the Prize was awarded to Nadia Murad Basee Taha and Lamiya Aji Bashar - survivors of sexual enslavement by Islamic State who have beco- me spokespersons for women afflicted by IS’s campaign of sexual violence. The European Parliament Information Offices (EPIOs) promoted the Sakha- rov Prize via various events and actions organised within the scope of the wider, year-long Human Rights campaign of the European Parliament, rai- sing awareness of the EP’s commitment to the protection of human rights around the world. This -

Press Release 09-11-2015 - 15:57 Reference No: 20151109IPR01724

Press release 09-11-2015 - 15:57 Reference No: 20151109IPR01724 Final round of 2015 LUX Film competition: screenings and debates with directors The final round of the ninth edition of the 2015 LUX Film Prize competition starts in Brussels on Monday. It includes three screenings, live debates with audiences and two weeks in which the three shortlisted films –Mediterranea, Mustang and Urok (The Lesson) – will be shown at the EP, with MEPs voting for the winning film and audiences choosing their favourites. Screenings at the EP run from 9 to 20 November. The films will also be presented at Bozar in Brussels on 10 and 11 November and Mediterranea will be shown simultaneously in eight European cities. Mediterranea will be relayed from Bozar, on Wednesday, 11 November, to cinemas in Aarhus, Seville, Cork, Bratislava, Paris, Lisbon, Santiago de Compostela and Bucharest. The director, Jonas Carpignano, will and will take part, from Bruissels, in a live debate with the audience after the film via Twitter (#luxprize), which will be livestreamed to all the cinemas taking part. ARTE TV will also broadcast the debate on its website. Audiences across Europe are invited join the discussion on Twitter and send their questions to the director. The films will also be screened twice a day at the European Parliament from 9 to 20 November. MEPs will be able to vote for their favourite film up to 23 November and the winner will be announced when the voting has closed. The prize will be awarded on 24 November at a ceremony in Strasbourg. The three films shortlisted for the 2015 LUX Prize All three films deal with contemporary European social issues such as immigration, the role of local conservative traditions and economic problems in society. -

No.3, 2017 (November)

No.3, 2017 (November) Internet /Tech Industry EU Guidelines for Platforms to Tackle Hate Speech Online p.2 Guidelines on Hate Speech a Threat to Online Expression? P.2 Continued EU Hunt on Tax-Evading Tech Giants p.3 EU Debate on Taxing Digital Companies p.3 U.S.Lawmakers Critical of Silicon Valley Too p.4 U.S.Net Neutrality Rules To Be Scrapped? P.5 EU Rules for Free Flow of Non-Personal Data Proposed p.5 Freedom of Expression EU Policymakers Appalled by Murder of Top Investigative Journalist p.6 Parliament Wants Tough EU Law to Protect Whistleblowers p.7 Much Criticism of Censorship in Catalonia But EU Silent p.7 New OSCE Representative Builds Coalition To Defend Media Freedom p.8 Copyright Copyright reform: Controversial Upload Filters in Focus p.8 Geo-Blocking Rules: Music and e-Books Not Covered p.9 New Online Broadcasting Rules: Only More News Across Borders? p.10 Privacy Data Protection EU Parliament Wants Strong e-Privacy Rules p.11 e-Privacy rules: Tech Giants, Advertisers and Media Up In Arms p.12 EU Data Protection Rules Give Competitive Advantage? P.12 Encryption: Police Access to Encrypted Data Without Backdoors? P.13 Media – general EU Commission Calls For Advice on Fake News p.13 Hearing in Parliament about Fake News p.14 Brexit To Affect International Broadcasters and Creative Workers? P.14 Twitter Vital in Modern Political Communication? p.15 Nordic Coproduction Wins LUX Film Prize p.15 1 Internet / Tech Industry EU Guidelines for Platforms to Tackle Hate Speech Online Many governments have become increasingly concerned about the wave of hate speech spreading via social networks. -

Agenda EN Conference Will Take Place at 15.30

The Week Ahead 25 November – 01 December 2019 Plenary session, Strasbourg Plenary session, Strasbourg Election of the European Commission. As Parliament’s President and political group leaders declared the public hearings of candidates closed, Ursula von der Leyen, President-elect of the European Commission, will present her team of Commissioners- designate to Parliament and discuss the new Commission’s objectives with MEPs. Parliament will then decide (by simple majority) whether to approve the College of Agenda Commissioners in its entirety. If elected, the European Commission will take up office on 1 December. A press conference by President Sassoli and President-elect von der Leyen is scheduled for 13.30 (Wednesday) Climate Emergency/COP25. MEPs will debate the climate and environmental emergency and discuss how to ensure that the EU leads in countering climate change, ahead of the UN climate change conference (COP25) in Madrid on 2-13 December. There will be a vote on two draft resolutions calling for the EU to commit to cutting greenhouse gas emissions to make the EU reach climate neutrality by 2050. (Debates Monday, votes Thursday) EU budget 2020. Next year’s budget for investing in the EU and its member states, which was agreed with the Council on 18 November, will be put to the plenary vote and immediately signed into law by Parliament’s President. (Debate Tuesday, vote Wednesday ) EU summit. MEPs, First Commission Vice-President Frans Timmermans and a representative of the Finnish Presidency will discuss Parliament’s priorities in anticipation of the European Council meeting (Brussels, 12-13 December). The main topics on the summit agenda are the EU long-term budget, EU climate change strategy, and external relations. -

LUX Film Prize Finalists' Plea to EU Decision Makers

Press Release Brussels, 13 November 2018 LUX Film Prize finalists’ plea to EU decision makers: audiovisual creators should be linked to the life of their works On the occasion of the European Parliament LUX Film Prize Award Ceremony on 14 November, LUX Prize finalists since 2007 are calling in an open letter on Member States and the European Commission to take on board the Parliament’s proposal to introduce a principle of fair and proportionate remuneration for authors and performers in the proposed Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market. The LUX Film Prize is a unique platform for European filmmakers’ works to reach European audiences at large by providing visibility and subtitles in the EU official languages. In order to foster a vibrant creative environment at a time when the online exploitation of audiovisual works is increasing, European filmmakers are calling on EU institutions to support them in finally sharing in the economic success of their work. Following the adoption of the European Parliament’s position on the proposed Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market on 12 September, interinstitutional negotiations have started, with the objective of reaching an agreement by the end of the year. The European Parliament proposed to introduce a much-needed principle of fair and proportionate remuneration for authors and performers, leaving flexibility to Member States on the choice of the implementation instrument (collective bargaining agreements, collective management of rights, statutory remuneration mechanisms) provided that authors and performers receive remuneration from the revenues derived from the exploitation of their works. Quotes “Representative organisations of screenwriters and directors have asked for it, more than 21,000 petition signatories support it, The European Parliament proposed it and now we, the finalists of the LUX Film Prize, call for it. -

Polish Culture Yearbook 2017

2017 POLISH CULTURE YEARBOOK 2017 POLISH CULTURE YEARBOOK Warsaw 2018 TENETS OF CULTURAL POLICY FOR 2018 2017 Prof. Piotr Gliński, Minister of Culture and National Heritage 5 REFLECTIONS ON CULTURE FROM AN INSTITUTIONAL PERSPECTIVE Prof. Rafał Wiśniewski, Director of the National Centre for Culture 13 TABLE O CONTENTS TABLE 1. CENTENARY CELEBRATIONS OF THE REPUBLIC OF POLAND REGAINING INDEPENDENCE 17 THE MULTI-ANNUAL GOVERNMENTAL ‘NIEPODLEGŁA’ PROGRAM (Ed. Office of the ‘Niepodległa’ Program) 18 2. FIELDS OF CULTURE AND NATIONAL HERITAGE 27 POLISH STATE ARCHIVES (Ed. Head Office of Polish State Archives) 28 LIBRARIES (Ed. The National Library) 38 CULTURAL CENTRES (Ed. Centre for Cultural Statistics, Statistical Office in Kraków) 52 POLISH CULTURE YEARBOOK POLISH CULTURE CINEMATOGRAPHY (Ed. Polish Film Institute) 60 MUSEUMS (Ed. National Institute for Museums and Public Collections) 69 MUSIC (Ed. Institute of Music and Dance) 82 PUBLISHING PRODUCTION - BOOKS AND MAGAZINES (Ed. The National Library) 90 BOOK MARKET – THE CREATIVE ECONOMY (Ed. Book Institute) 98 ART EDUCATION (Ed. Centre for Art Education) 104 DANCE (Ed. Institute of Music and Dance) 113 THEATRE (Ed. Zbigniew Raszewski Theatre Institute) 118 HISTORICAL MONUMENTS: THE STATE OF CONSERVATION (Ed. National Heritage Board of Poland) 128 3. POLISH CULTURE ABROAD 141 POLISH CULTURAL HERITAGE ABROAD (Ed. Ministry of Culture and National Heritage Department of Cultural Heritage Abroad and Wartime Losses ) 142 NATIONAL MEMORIAL SITES ABROAD (Ed. Ministry of Culture and National Heritage Department of Cultural Heritage Abroad and Wartime Losses ) 162 RESTITUTION OF CULTURAL PROPERTY (Ed. Ministry of Culture and National Heritage Department of Cultural Heritage Abroad and Wartime Losses) 169 4.