Canada: Imperialist Or Imperialized? Paper Presented To: IX Encuentro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Victims Rule

1 24 JEWISH INFLUENCE IN THE MASS MEDIA, Part II In 1985 Laurence Tisch, Chairman of the Board of New York University, former President of the Greater New York United Jewish Appeal, an active supporter of Israel, and a man of many other roles, started buying stock in the CBStelevision network through his company, the Loews Corporation. The Tisch family, worth an estimated 4 billion dollars, has major interests in hotels, an insurance company, Bulova, movie theatres, and Loliards, the nation's fourth largest tobacco company (Kent, Newport, True cigarettes). Brother Andrew Tisch has served as a Vice-President for the UJA-Federation, and as a member of the United Jewish Appeal national youth leadership cabinet, the American Jewish Committee, and the American Israel Political Action Committee, among other Jewish organizations. By September of 1986 Tisch's company owned 25% of the stock of CBS and he became the company's president. And Tisch -- now the most powerful man at CBS -- had strong feelings about television, Jews, and Israel. The CBS news department began to live in fear of being compromised by their boss -- overtly, or, more likely, by intimidation towards self-censorship -- concerning these issues. "There have been rumors in New York for years," says J. J. Goldberg, "that Tisch took over CBS in 1986 at least partly out of a desire to do something about media bias against Israel." [GOLDBERG, p. 297] The powerful President of a major American television network dare not publicize his own active bias in favor of another country, of course. That would look bad, going against the grain of the democratic traditions, free speech, and a presumed "fair" mass media. -

Canada's Location in the World System: Reworking

CANADA’S LOCATION IN THE WORLD SYSTEM: REWORKING THE DEBATE IN CANADIAN POLITICAL ECONOMY by WILLIAM BURGESS BA (Hon.), Queens University, 1978 MA (Plan.), University of British Columbia, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Geography We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA January 2002 © William Burgess, 2002 Abstract Canada is more accurately described as an independent imperialist country than a relatively dependent or foreign-dominated country. This conclusion is reached by examining recent empirical evidence on the extent of inward and outward foreign investment, ownership links between large financial corporations and large industrial corporations, and the size and composition of manufacturing production and trade. -

Senate Halts As Students Walk

Campagne de souscription CapitalCampaign de l'UniversiteConcordia Concordia University Batisoons ensemble ~ Building together Senate halts as students walk out By Carole l{leingrib Senate's first a ttempt to debate the five Calling the Phase II report a " mother poss ible m issions fo r Concordia men hood statement," the students said the tioned in the Ph ase 11 report of the Univer document should be re-written in order to ' sity's Mi ssio n and Strategy-Development " re-focus its direction ." Study never got off the ground last Friday· On another front, Division I Dean Don because 13 studen ts senators walked out, T addeo presented Sena te with his own forcing the cha irman to adjourn for lack "ana lys is o f the situa ti on and interpreta of quorum. ti on of the Phase II report" . Speaking " not T he student senators had earlier pres as a member o f the Phase II Steering ented two motions, one calling for the Committee nor as Dean of Div ision I, bu t Phase II report to be re-written; the otheF rather as a member of Sena te," Taddeo requesti n-g that stud ents. a n d fa culty expressed his concern abo ut wha t he feels members be repn::sented on the Committee is the lack o f any cl ear context for d iscus on Institutional Strategy formed to over sion of the•Mi ~sion Study issue, see implemen tation of the Miss ion Study, Taddeo suppli_ed da ta o n Concordia 's The first motion was defeated; the second place in the Quebec unive rsity network, was ta bl ed. -

The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm: a History of Corporate Ownership in Canada

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: A History of Corporate Governance around the World: Family Business Groups to Professional Managers Volume Author/Editor: Randall K. Morck, editor Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-53680-7 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/morc05-1 Conference Date: June 21-22, 2003 Publication Date: November 2005 Title: The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm: A History of Corporate Ownership in Canada Author: Randall Morck, Michael Percy, Gloria Tian, Bernard Yeung URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10268 1 The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm A History of Corporate Ownership in Canada Randall K. Morck, Michael Percy, Gloria Y. Tian, and Bernard Yeung 1.1 Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century, large pyramidal corporate groups, controlled by wealthy families or individuals, dominated Canada’s large corporate sector, as in modern continental European countries. Over several decades, a large stock market, high taxes on inherited income, a sound institutional environment, and capital account openness accompa- nied the rise of widely held firms. At mid-century, the Canadian large cor- porate sector was primarily freestanding widely held firms, as in the mod- ern large corporate sectors of the United States and United Kingdom. Then, in the last third of the century, a series of institutional changes took place. These included a more bank-based financial system, a sharp abate- Randall K. Morck is Stephen A. Jarislowsky Distinguished Professor of Finance at the University of Alberta School of Business and a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research. -

Major Sectoral Developments

September 1986 Major Sectoral Developments The following section focuses on major investment transaction trends in the more active industrial sectors during 1985. Metal Mining (SIC 10) - Foreign direct investment in U.S. metal mining firms, at a low ebb for the past few years, rebounded slightly in 1985. Concerns over political instability abroad, country debt repayment problems and a weakening U.S. dollar were factors that accounted for increased foreign investment in this sector. In 1985,10 completed transactions were identified; 7 of them had a total value or $124.4 million, a four-fold increase over the 1984 figure. The largest transaction was the acquisition of Copper Range Co. by Echo Bay Mines Ltd. of Edmonton, Canada for $55 million. Echo Bay Mines, operator of Canada's second largest gold mine, will expand its interests through the purchase of Copper Range which has several gold exploration projects in Nevada as well as copper interests in Michigan. The second largest transaction was the addition of a new mill at Newmont Mining Corp.'s Carlin gold mine in northeastern Nevada valued at $33.9 million. Newmont Mining is 26.1 percent owned by Consolidated Gold Fields Ltd. of England, itself 29 percent owned by Minorco, a Bermuda-based firm controlled by Anglo-American Corp. of South Africa Ltd. Canada was the primary source country for investors in the metal mining sector in 1985. Canadian investors accounted for almost half of the transactions (5). In second place were investors from the United Kingdom with 2 transactions. These investments were largely mine expansions (4) or acquisitions (3). -

Thank You NEWS What Makes a City Great?

NEWS BULLETIN 26 October 2012 Please forward and distribute widely - thank you NEWS What Makes a City Great? was the topic of CBC Radio show “Ontario Today” on October 25th when Cities Centre Interim Director Richard Stren was a featured participant. Hosted by Kathleen Petty and aired on Radio One on a weekly basis, the program is an Ontario-wide news and current affairs phone-in program. Past episodes are posted ….more Just released: The Impact of Precarious Legal Status on Immigrants’ Economic Outcomes by Professor Luin Goldring of York University and Cities Centre Research Associate Professor Patricia Landolt, Chair of the Department of Sociology, UTSC. The new study is published by the Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP) …more and download Cities Centre congratulates former Director, Professor Eric Miller on being chosen as the inaugural recipient of the new UBC Margolese National Design for Living Prize. “Dr. Miller has been an extraordinary force for the development and improvement of urban living environments in Canada,“ says UBC Applied Science’s Dean pro tem Eric Hall. The prize of $50,000 will be awarded annually to a Canadian who has made outstanding contributions to the development or improvement of living environments for Canadians of all economic classes. Professor Miller will travel to Vancouver to give a public lecture in early 2013 …more The Toronto Community Foundation has announced a Call for Applications for Vital Ideas Grants. The Vital Ideas program is open to any charitable organization registered with -

Business Groups in Canada: Their Rise and Fall, and Rise and Fall Again

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES BUSINESS GROUPS IN CANADA: THEIR RISE AND FALL, AND RISE AND FALL AGAIN Randall Morck Gloria Y. Tian Working Paper 21707 http://www.nber.org/papers/w21707 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2015 We are grateful for very helpful comments from Asli M. Colpan, Takashi Hikino, Franco Amatori, Tetsuji Okazak and participants in Kyoto University’s conference on Business Groups in Developed Economies and in the 2015 World Economic History Congress. We are grateful to the Bank of Canada for partial funding. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2015 by Randall Morck and Gloria Y. Tian. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Business Groups in Canada: Their Rise and Fall, and Rise and Fall Again Randall Morck and Gloria Y. Tian NBER Working Paper No. 21707 November 2015 JEL No. G3,L22,N22 ABSTRACT Family-controlled pyramidal business groups were important in Canada early in the 20th century, amid rapid catch-up industrialization, but largely gave way to widely held free-standing firms by mid- century. In the 1970s and early 1980s – an era of high inflation, financial reversal, unprecedented state intervention, and explicit emulation of continental European institutions – pyramidal groups abruptly regained prominence. -

Who-Owns-Canada.Pdf

summary The Imperialist Nature of the PART 1: Who Controls the Economy? PART2: Canadian Bourgeoisie The concept of imperialism • Concentration and • Control of capital monopoly — The early 1900s — Concentration today • The strongholds of the Ca• nadian Bourgeoisie • Financial capital and the — Canadian giants in each financial oligarchy sector of the economy — The creation of Canadian finance capital at the — State corporations beginning of the 20th century — Canada's banks — Finance capital today — The financial oligarchy • The export of capital • The place of US imperialism — Who controls Canada's in the Canadian economy export of capital? — Fluctuations in US control — In which economic sectors — Tendency to decline since is Canadian foreign 1970 investment found? — The present state of US domination • The division of the world. — Canadian participation in the economic division of the world — Canada and the territorial • Who controls the strategic division of the world sectors of Canada's — The question of colonies economy? 8 9 Who owns Canada? Who controls the economy While other writers admit an independent Canadian —Canadian or foreign capitalists? bourgeoisie was able to develop, they insist that it This question has long been at the heart of quickly fell under US domination. debates among those who are committed to fighting Mel Watkins (4), for example, maintains that capitalism in our country. For by determining who around the turn of the century "the indigenous bour• controls economic and thus political power in Canada, geoisie dominates foreign capital and the state..."(5). we can identify the main enemy in our struggle for But the US rapidly turned Canada into a neo-colony. -

Our Time to Lead Contributions to Knowledge Building & Professional Development from the Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing

Our Time to Lead Contributions to knowledge building & professional development from the Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing October 2016 Special Events The Council of Agencies Serving South Asians (CASSA) CONGRATULATIONS TO ALL!! and Dr. Sepali Guruge (in her capacity as Research Chair th Excellent nursing scholarship was evident at The in Urban Health) organized this year’s 6 Health Equity CNSA Ontario-Quebec 2016 Regional Summit, which was held on Sep. 27, at the Sears Atrium at conference at the Metro Toronto Convention Ryerson University. Centre, September 30 to October 2, 2016! It was The event was attended by more than 75 academics, a huge success and the conference hosts and community agency representatives, and community organizers were our own DCSN students! members. Among the presenters were Drs. Usha George, The theme: Building the Future: Inspiring the Mandana Vahabi, and Purnima George from Ryerson Next Generation of Nurses, drew presentations University. The focus of the summit was ‘Health and and posters that directed student focus to create Wellbeing of South Asian Immigrants.’ Taking a lifespan brighter, healthier world. Our nursing students approach, the presenters addressed topics such as mental are demonstrating that everyone makes a health, sexual and reproductive health, violence against difference. Congratulations to the students! women, and elder abuse. The summit strengthened community collaborations and created a valuable Congratulations to all members of the opportunity to build new network with organizations across Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing! the province that work with various South Asian Elaine Santa Mina communities in Ontario. Interim Director Youth Dementia Awareness Networking Event & Symposium and Mindfest For photos and comprehensive stories about these events, please flip to the end of the newsletter. -

Fault Manb* Brtfttooob SECOND SECTION

SECOND SECTION fault Manb* Brtfttooob WEDNESDAY, MAY 25. 1988 • B1 Carnival has Coffee benefit will games, food for everyone offset licensing cost A coffeehouse benefit has been Sigurgeirson's residence. Visitors to Salt Spring Elemen• planned to help offset licensing The school caters to 10 children tary School's annual carnival will costs of the Under the Rainbow between the ages of three and have the opportunity to feast on Nursery School. five years. The children attend barbecued food, travel through a The May 27 event at St. the program for two and a half haunted house and participate in George's Church Hall will be hours twice weekly. a number of games and sales. followed by an open house at the The carnival, organized by the 124 Westcott Road pre-school on Unlike the Ganges pre-school, school's Parents' Group, will be Sunday, May 29. run from the Community Centre, held throughout the Salt Spring Under the Rainbow is not a Elementary building, beginning Under the Rainbow co• parent-participation program. Si• after school on Friday, May 27. ordinator Lisa Sigurgeirson says gurgeirson feels some parents Unlike previous years, greater the coffee benefit will help cover can't afford that amount of time. family participation will be en• the expense of licensing the However, parents do take part in couraged with the availability of school — something she has been one or two fund-raisers every year dinner. working towards since the estab• — such as a trike-a-thon last year Two of the organizers, Anne lishment of a play group there two — plus a spring and fall work McKerricher and Cherry Jensen, years ago. -

Looking at Me 10 Canadian Self-Portraits

LOOKING AT ME 10 CANADIAN SELF-PORTRAITS When artists become their own subjects Self-portraits are opportunities for artists to play with their identities in innovative and engaging ways. Whether experimenting with a new medium and trying out techniques, promoting a career, or contemplating the face and the body, artists have found endless reasons to create portraits of themselves. In the spirit of summer as a time to pause and reflect, we’re sharing the following ten Canadian self-portraits which offer insights into both their creators and our country. Sara Angel Founder and Executive Director, Art Canada Institute DOUBLE TROUBLE Shuvinai Ashoona and Shary Boyle, Self Portrait (detail), 2015, private collection Two of Canada’s leading contemporary artists—Shuvinai Ashoona and Shary Boyle (both past recipients of the prestigious Gershon Iskowitz Prize)— created this double self-portrait. Kinngait (Cape Dorset)-based Ashoona and Toronto-based Boyle first collaborated in 2011 when the latter visited the Arctic. Self Portrait was created for their joint 2015 exhibition Universal Cobra (organized by Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain in partnership with Feheley Fine Arts), which featured six co-created works for which each artist prepared part of a drawing, leaving white space for her counterpart to fill. This work includes references to Ashoona’s and Boyle’s shared interests and practices, from the drawing papers scattered at their feet to their mutual love of bright colours and playful patterns. Learn More MAN IN THE MIRROR Ozias Leduc, Self-Portrait with Camera (Autoportrait à la caméra) (detail), c.1899, BAnQ Vieux-Montréal In 1899 Quebec artist Ozias Leduc created this photograph as part of a body of self-portraits that also includes drawings and a painting. -

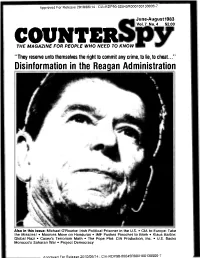

Counterspy: Disinformation in the Reagan Administration

Approved For Release 2010/06/14: CIA-RDP90-00845R000100130006-7 June-August 1983 Vol. 7 No. 4 $2.00 COUNTERTHE MAGAZINE FOR PEOPLE WHO NEED TO KNOW "They reserveunto themselves the right to commit any crime, to lie, to cheat. .. " Disinformation in the Reagan Administration Also in this issue: Michael O'Rourke: Irish Political Prisoner in the U.S. • CIA to Europe: Take the Missiles! • Moonies Move on Honduras • IMF Pushes Pinochet to Brink • Klaus Barbie: Global Nazi • Casey's Terrorism Math • The Pope Plot: CIA Production, Inc. • U.S. Backs Morocco's Saharan War • Project Democracy Approved For Release 2010/06/14: CIA-RDP90-00845R000100130006-7 Approved For Release 2010/06/14: CIA-RDP90-00845R000100130006-7 CounterSpy Statement of Purpose: The United States emerged from World War II as the world's dominant political and economic power, To conserve and enhance this power, the U.S. govern ment created a variety of institutions to secure dominance over "free world" nations which supply U.S. corporations with cheap labor, raw materials, and markets. A number of these in stitutions, some initiated jointly with allied Western European governments, have systemat ically violated the fundamental rights and freedoms of people in this country and the world over. Prominent among these creations was the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), born in 1947. Since 1973, CounterSpy magazine has exposed and analyzed such intervention in all its facets: covert CIA operations, U.S. interference in foreign labor movements, U.S. aid in cre ating foreign intelligence agencies, multinational corporations-intelligence agency link-ups, and World Bank assistance for counterinsurgency, to name but a few.