1 2018 United States Voluntary National Cetacean Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captive Orcas

Captive Orcas ‘Dying to Entertain You’ The Full Story A report for Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS) Chippenham, UK Produced by Vanessa Williams Contents Introduction Section 1 The showbiz orca Section 2 Life in the wild FINgerprinting techniques. Community living. Social behaviour. Intelligence. Communication. Orca studies in other parts of the world. Fact file. Latest news on northern/southern residents. Section 3 The world orca trade Capture sites and methods. Legislation. Holding areas [USA/Canada /Iceland/Japan]. Effects of capture upon remaining animals. Potential future capture sites. Transport from the wild. Transport from tank to tank. “Orca laundering”. Breeding loan. Special deals. Section 4 Life in the tank Standards and regulations for captive display [USA/Canada/UK/Japan]. Conditions in captivity: Pool size. Pool design and water quality. Feeding. Acoustics and ambient noise. Social composition and companionship. Solitary confinement. Health of captive orcas: Survival rates and longevity. Causes of death. Stress. Aggressive behaviour towards other orcas. Aggression towards trainers. Section 5 Marine park myths Education. Conservation. Captive breeding. Research. Section 6 The display industry makes a killing Marketing the image. Lobbying. Dubious bedfellows. Drive fisheries. Over-capturing. Section 7 The times they are a-changing The future of marine parks. Changing climate of public opinion. Ethics. Alternatives to display. Whale watching. Cetacean-free facilities. Future of current captives. Release programmes. Section 8 Conclusions and recommendations Appendix: Location of current captives, and details of wild-caught orcas References The information contained in this report is believed to be correct at the time of last publication: 30th April 2001. Some information is inevitably date-sensitive: please notify the author with any comments or updated information. -

Page 1297 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 917B

Page 1297 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 917b 1923, as amended’’ on authority of Pub. L. 89–554, § 7(b), classified principally to chapter 38 (§ 1801 et seq.) of this Sept. 6, 1966, 80 Stat. 631 (the first section of which en- title. For complete classification of this Act to the acted Title 5, Government Organization and Employ- Code, see Short Title note set out under section 1801 of ees), and of section 1106(a) of act Oct. 28, 1949, ch. 782, this title and Tables. title XI, 63 Stat. 972, which provided that references in MENDMENTS other laws to the Classification Act of 1923 shall be con- A sidered to mean the Classification Act of 1949. 1996—Par. (3). Pub. L. 104–208 substituted ‘‘Magnuson- In cl. (b), ‘‘subchapter I of chapter 57 of title 5 and Stevens Fishery’’ for ‘‘Magnuson Fishery’’. section 5731(a) of title 5’’ substituted for ‘‘the Travel 1980—Par. (3). Pub. L. 96–561 substituted ‘‘Magnuson Expense Act of 1949 and section 10 of the Act of March Fishery Conservation and Management Act’’ for ‘‘Fish- 3, 1933 (U.S.C., title 5, sec. 73b)’’ on authority of Pub. L. ery Conservation and Management Act of 1976’’. 89–554, § 7(b), Sept. 6, 1966, 80 Stat. 631, the first section of which enacted Title 5. EFFECTIVE DATE OF 1996 AMENDMENT In cl. (e), ‘‘section 501 of title 44’’ substituted for Section 101(a) [title II, § 211(b)] of div. A of Pub. L. ‘‘section 11 of the Act of March 1, 1919 (U.S.C., title 44, 104–208 provided that the amendment made by that sec- sec. -

Whale Conservation in Coastal Ecuador : Environmentalism of the Poor Or Neoliberal Conservation ?*

Revista Iberoamericana 25.2 (2014 ): 1-33. Whale Conservation in Coastal Ecuador : Environmentalism of the Poor or Neoliberal Conservation ?* Bradley Tatar Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology [UNIST] Tatar, Bradley (2014), Whale Conservation in Coastal Ecuador: Environmentali sm of the Poor or Neoliberal Conservation? In this p aper, I examine the interaction between transnational activist Abstract networks, conservation scientists, government authorities, and artisanal fish ing communities in coastal Ecuador. Focusing on the problem of cetacean bycatch, I employ the concept of the “discourse of nature” to identify contrasting languages of valuation used by the stakeholders for marine coastal environments. NGOs utilize a scientific evaluation to portray artisanal fishing as a hazard to the survival of hum pback whales, but this coincides with the attempt by government and development agencies to portray artisanal fisheries as inefficient and ecologically harmful. In contrast, a survey I carried out in a coastal fishing community shows that local residents contest this portrayal of fishing as ecologically harmful, drawing upon their discourses of livelihood, indigenous identity, territorial claims, and social marginality. Focusing on the social conflict surrounding the marine protected area [MPA] of Machalilla National Park, I argue that additional restrictions on fishing to mitigate the incidence of cetacean bycatch will not have adequate social acceptance by local artisan fishing communities. Hence, the language of whale conservation which appears to be a pro-poor environmentalism at the macro (international) level, appears to local actors as a threat to their livelihoods. To offset this micro/macro discrepancy, whale conservation NGOs should support local aspirations to continue fishing as a livelihood, thereby * This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2012S1A5A8024090). -

The Regulatory Framework for Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises in European Waters

The Regulatory Framework for Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises in European Waters Andrea Ripol, Seas At Risk, Brussels, Belgium and Mirta Zupan, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences and Ghent University, Belgium No EU citizen wants to eat fish that has been caught at the expense of iconic species like dolphins or whales. The legal framework to prevent the killing of marine mammals exists, now it is just a matter of political will to implement it. Andrea Ripol © Tilen Genov, Morigenos © Tilen Genov, 28 Overview of Cetacean Species in European Waters (including Red List Status) Introduction Interest in whale conservation began in earnest in the late 1940s largely as a response to the unsustainable pressure placed on whale populations by intensified commercial whaling. At first, the aim was to conserve populations in order to continue harvesting them. In the 1970s, as environmental activism heightened, several international agreements for nature protection were signed, including the Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats and the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). Today, in addition, cetaceans in European Union (EU) waters are strictly protected by the EU‘s Habitats Directive, as well as the Marine Strategy Framework Directive, which intends to prevent human-induced decline of biodiversity, targets various pressures and threats and tries to achieve a good environmental status in EU waters. Legal framework in Europe Habitats Directive and the Natura 2000 network The protection of cetaceans in the EU is primarily driven by the Habitats Directive (Council Directive 92/43/EEC), a cornerstone of EU legislation for nature protection, adopted in 1992 (Council of the European Communities, 1992). -

SOLUTION: Gathering and Sonic Blasts for Oil Exploration Because These Practices Can Harm and Kill Whales

ENDANGEREDWHALES © Nolan/Greenpeace WE HAVE A PROBLEM: WHAT YOU CAN DO: • Many whale species still face extinction. • Tell the Bush administration to strongly support whale protection so whaling countries get the • Blue whales, the largest animals ever, may now number as message. few as 400.1 • Ask elected officials to press Iceland, Japan • Rogue nations Japan, Norway and Iceland flout the and Norway to respect the commercial whaling international ban on commercial whaling. moratorium. • Other threats facing whales include global warming, toxic • Demand that the U.S. curb global warming pollution dumping, noise pollution and lethal “bycatch” from fishing. and sign the Stockholm Convention, which bans the most harmful chemicals on the planet. • Tell Congress that you oppose sonar intelligence SOLUTION: gathering and sonic blasts for oil exploration because these practices can harm and kill whales. • Japan, Norway and Iceland must join the rest of the world and respect the moratorium on commercial whaling. • The loophole Japan exploits to carry out whaling for “Tomostpeople,whalingisallnineteenth- “scientific” research should be closed. centurystuff.Theyhavenoideaabout • Fishing operations causing large numbers of whale hugefloatingslaughterhouses,steel-hulled bycatch deaths must be cleaned up or stopped. chaserboatswithsonartostalkwhales, • Concerted international action must be taken to stop andharpoonsfiredfromcannons.” other threats to whales including global warming, noise Bob Hunter, pollution, ship strikes and toxic contamination. -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 75/Wednesday, April 21, 2021

21082 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 75 / Wednesday, April 21, 2021 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Lisa Network, and the Wishtoyo Foundation Manning, NMFS, Office of Protected filed a complaint seeking court-ordered National Oceanic and Atmospheric Resources, 301–427–8466. deadlines for the issuance of proposed Administration SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: and final rules to designate critical habitat for the CAM, MX, and WNP 50 CFR Parts 223, 224, and 226 Background DPSs of humpback whales. See Center Under the ESA, we are responsible for for Biological Diversity et al. v. National [Docket No. 210415–0080] determining whether certain species are Marine Fisheries Service, et al., No. threatened or endangered, and, to the 3:18–cv–01628–EDL (N.D. Cal.). The RIN 0648–BI06 maximum extent prudent and parties entered into a settlement determinable, designating critical agreement with the approval and Endangered and Threatened Wildlife habitat for endangered and threatened oversight of the court, and subsequently and Plants: Designating Critical species at the time of listing (16 U.S.C. amended the dates specified in the Habitat for the Central America, 1533(a)(3)(A)(i)). On September 8, 2016, original order. The amended settlement Mexico, and Western North Pacific we published a final rule that revised agreement stipulated that NMFS submit Distinct Population Segments of the listing of humpback whales under a proposed determination concerning Humpback Whales the ESA by removing the original, the designation of critical habitat for taxonomic-level species listing, and in these three DPSs to the Federal Register AGENCY: National Marine Fisheries its place listing four DPSs as endangered by September 26, 2019. -

The Action Plan for Australian Cetaceans J L Bannister,* C M Kemper,** R M Warneke***

The Action Plan for Australian Cetaceans J L Bannister,* C M Kemper,** R M Warneke*** *c/- WA Museum, Francis Street, Perth WA 6000 ** SA Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, SA 5000 ***Blackwood Lodge, RSD 273 Mount Hicks Road, Yolla Tasmania 7325 Australian Nature Conservation Agency September 1996 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Commonwealth Government, the Minister for the Environment, Sport and Territories, or the Director of National Parks and Wildlife. ISBN 0 642 21388 7 Published September 1996 © Copyright The Director of National Parks and Wildlife Australian Nature Conservation Agency GPO Box 636 Canberra ACT 2601 Cover illustration by Lyn Broomhall, Perth Copy edited by Green Words, Canberra Printer on recycled paper by Canberra Printing Services, Canberra Foreword It seems appropriate that Australia, once an active whaling nation, is now playing a leading role in whale conservation. Australia is a vocal member of the International Whaling Commission, and had a key role in the 1994 declaration of the Southern Ocean Sanctuary. The last commercial Australian whaling station ceased operations in Albany in 1978, and it is encouraging to see that once heavily exploited species such as the southern right and humpback whales are showing signs of recovery. Apart from the well-known great whales, Australian waters support a rich variety of cetaceans: smaller whales, dolphins, porpoises and killer whales. Forty-three of the world’s 80 or so cetacean species are found in Australia. This diversity is a reflection of our wide range of coastal habitats, and the fact that Australia is on the main migration route of the great whales from their feeding grounds in the south to warmer breeding grounds in northern waters. -

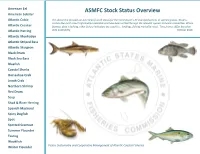

ASMFC Stock Status Overview

American Eel ASMFC Stock Status Overview American Lobster Atlantic Cobia This document provides an overview of stock status for the Commission’s 27 managed species or species groups. Graphs contain the most recent information available and have been vetted through the relevant species technical committee. Where Atlantic Croaker biomass data is lacking, other fishery indicators are used (i.e., landings, fishing mortality rates). Time frames differ based on Atlantic Herring data availability. October 2020 Atlantic Menhaden Atlantic Striped Bass Atlantic Sturgeon Black Drum Black Sea Bass Bluefish Coastal Sharks Horseshoe Crab Jonah Crab Northern Shrimp Red Drum Scup Shad & River Herring Spanish Mackerel Spiny Dogfish Spot Spotted Seatrout Summer Flounder Tautog Weakfish Vision: Sustainable and Cooperative Management of Atlantic Coastal Fisheries Winter Flounder Quick Guide to ASMFC Species Stock Status (Current as of October 2020) = Rebuilt/Sustainable / = Recovering/Rebuilding = Depleted ? = Unknown *= Concern STATUS/ REBUILDING STATUS & SPECIES OVERFISHED OVERFISHING TRENDS SCHEDULE 2017 stock assessment update American Eel Depleted Unknown indicates resource remains depleted. GOM/GBK stock abundance Gulf of Maine/ has increased since the 1980s. American Georges Bank Not Depleted N 2020 benchmark assessment to Lobster (GOM/GBK) be presented to the Board in October. SNE stock has collapsed and is experiencing recruitment Southern New Depleted N failure. 2020 benchmark England assessment to be presented to the Board in October. Depleted on coastwide basis; Amendment 3 established 2013 moratorium unless river- American Shad Depleted Unknown specific sustainability can be documented; benchmark assessment scheduled for 2020. In 2020, the TLA was updated to incorporate additional fishery-independent surveys, Atlantic age and length information, an Unknown Unknown ? Croaker updated reference period, regional characteristics, and an updated management trigger mechanism. -

Kids for Whales Activities

Defending the Whales whales.greenpeace.org/us Kids for Whales Activities Table of Contents 1. Letter of Introduction 2. What Can We Do? 3. How to Petition 4. How to Write a Letter to the Editor & Sample Letter 5. How to Write a Letter to your Representative and Sample Letter 6. Whale Tale Defending the Whales whales.greenpeace.org/us 1. Letter of Introduction Dear Students and Teachers, It’s amazing to think that it was over thirty years ago that Greenpeace first set out to confront the whalers and save the whales. Three decades later, the image of Greenpeace activists placing themselves in front of the harpoons and putting their bodies on the line to defend the whales remains as powerful as ever. And it remains our most effective technique for shutting down the whalers when we are on the front lines in the Antarctic whaling grounds. Even though most people don’t think so, thousands of whales are hunted each year across our oceans. But as crucial as it is to get between the whalers and their harpoons, there is much more to saving the whales than pounding through the waves in an inflatable boat. Because ultimately, an end to commercial whaling will only come about through political pressure on the countries that support it. And no country is better positioned to apply that pressure than the United States. The US has historically been among the leading voices defending the whales, and this year, with the International Whaling Commission (IWC) meeting in Alaska in May, there are signs that it is rediscovering that voice. -

Buying Whales to Save Them | Issues in Science and Technology

9/26/2018 Buying Whales to Save Them | Issues in Science and Technology Buying Whales to Save Them by Ben A. Minteer, Leah R. Gerber Current policy approaches to manage whaling and protect whales are failing. It’s time to try a new approach that combines economic pragmatism and ethical principles. Since the beginning of the conservation movement in the late 19th century, decisionmakers facing environmental issues have struggled to square the impulse to respect nature’s dignity with more anthropocentric calculations of economic utility. It is a task that has often divided scientists, ethicists, and advocates S who share a regard for biodiversity and ecological integrity, yet dier on how such goals are to be justied and promoted in policy discourse. This debate has evolved over the years as new conservation initiatives and policy proposals have taken center stage, but the core of the dispute remains relatively unchanged: Does viewing species and ecosystems as economic goods preclude seeing them as objects of moral duty? Will the use of economic valuation methods extinguish rather than encourage public support for environmental protection? Can conservation really be expected to succeed by ignoring economic incentives bearing on the protection of wild populations and ecosystems? A recent proposal to create a “whale conservation market” has highlighted this stubborn ethics/economics divide in a very visible and contentious way. The whale market or “whale shares” idea presents an alternative to the traditional regulatory approach. By calling for the establishment of quotas that could be bought and sold, it allows conservation groups as well as whalers to purchase a xed number of whale shares, thereby providing a mechanism for whale protection as well as managed harvest. -

UNDER PRESSURE. the Need to Protect Whales and Dolphins In

UNDER PRESSURE The need to protect whales and dolphins in European waters The need to protect whales and dolphins in European waters April 2021 An OceanCare report. © OceanCare 2021 ISBN 978-3-033-08516-9 Editor: Laetitia Nunny, Wild Animal Welfare, La Garriga, Spain Cover image: © gettyimages Design: Roman Richter Suggested citation: OceanCare (2021) Under Pressure: The need to protect whales and dolphins in European waters. An OceanCare report. Copyright: The copyright of individual articles (including research articles, opinion pieces, conference proceedings, abstracts and images) remains the property of the authors. OceanCare Gerbestrasse 6 P.O.Box 372 CH-8820 Wädenswil Switzerland Tel: +41 (0) 44 780 66 88 https://www.oceancare.org OceanCare has been committed to marine wildlife protection since 1989. Through research and conservation projects, campaigns, environmental education, and involvement in a range of important international committees, OceanCare undertakes concrete steps to improve the situation for wildlife in the world’s oceans. OceanCare holds Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations (ECOSOC) and is a partner of the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM), the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS), and the UNEP/CMS Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS), as well as UNEP/MAP. OceanCare is accredited observer at the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). OceanCare has also been accredited as a Major Group to the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA), which is the governing body of UNEP and is a part of the UNEP Global Partnership on Marine Litter. -

Implementation of the Action Plan for the Conservation Ofmarine Mammals (Mmap) in the Widder Caribbean: a Scientific and Technical Analysis

UNITED NATIONS EP Distr. LIMITED UNEP(DEPI)/CAR WG.42/INF.29 Add.1 1 March 2021 Original: ENGLISH Ninth Meeting of the Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC) to the Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) in the Wider Caribbean Region Virtual meeting, 17–19 March 2021 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ACTION PLAN FOR THE CONSERVATION OFMARINE MAMMALS (MMAP) IN THE WIDDER CARIBBEAN: A SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL ANALYSIS For reasons of public health and safety associated with COVD-19, this meeting is being convened virtually. Delegates are kindly requested to access all meeting documents electronically for download as necessary. *This document has been reproduced without formal editing. Implementation of the Action Plan for the Conservation of Marine Mammals (MMAP) in the Wider Caribbean: A SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL ANALYSIS Implementation of the Action Plan for the Conservation of Marine Mammals (MMAP) in the Wider Caribbean: A SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL ANALYSIS November 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY including from all activities listed in Articles 11(1)(b) of Marine mammals hold a unique place in the collective the Protocol.2 pysche and economies of the Wider Caribbean Region (WCR). As a breeding and calving ground After more than a decade of MMAP-related for some whale species, the warm waters of the programmatic work under the SPAW Protocol, this Caribbean see the perennial return or residency of report compiles and reviews the status of major a diversity of majestic marine mammal species that threats to marine mammals of the region, and aims serve as a boost for tourism and source of inspiration to assess progress by countries towards achieving for some, or a valuable natural resource to be implementation of the MMAP since its adoption consumed or utilized by others.