Associations of Yoga Practice, Health Status, and Health Behavior Among

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

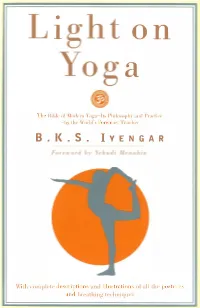

I on an Empty Stomach After Evacuating the Bladder and Bowels

• I on a Tllt' Bi11lr· ol' \lodt•nJ Yoga-It� Philo�opl1� and Prad il't' -hv thr: World" s Fon-·mo �l 'l'r·ar·lwr B • I< . S . IYENGAR \\ it h compldc· dt·!wription� and illustrations of all tlw po �tun·� and bn·athing techniqn··� With More than 600 Photographs Positioned Next to the Exercises "For the serious student of Hatha Yoga, this is as comprehensive a handbook as money can buy." -ATLANTA JOURNAL-CONSTITUTION "The publishers calls this 'the fullest, most practical, and most profusely illustrated book on Yoga ... in English'; it is just that." -CHOICE "This is the best book on Yoga. The introduction to Yoga philosophy alone is worth the price of the book. Anyone wishing to know the techniques of Yoga from a master should study this book." -AST RAL PROJECTION "600 pictures and an incredible amount of detailed descriptive text as well as philosophy .... Fully revised and photographs illustrating the exercises appear right next to the descriptions (in the earlier edition the photographs were appended). We highly recommend this book." -WELLNESS LIGHT ON YOGA § 50 Years of Publishing 1945-1995 Yoga Dipika B. K. S. IYENGAR Foreword by Yehudi Menuhin REVISED EDITION Schocken Books New 1:'0rk First published by Schocken Books 1966 Revised edition published by Schocken Books 1977 Paperback revised edition published by Schocken Books 1979 Copyright© 1966, 1968, 1976 by George Allen & Unwin (Publishers) Ltd. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Choreographers and Yogis: Untwisting the Politics of Appropriation and Representation in U.S. Concert Dance A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Jennifer F Aubrecht September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Chairperson Dr. Anthea Kraut Dr. Amanda Lucia Copyright by Jennifer F Aubrecht 2017 The Dissertation of Jennifer F Aubrecht is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I extend my gratitude to many people and organizations for their support throughout this process. First of all, my thanks to my committee: Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Anthea Kraut, and Amanda Lucia. Without your guidance and support, this work would never have matured. I am also deeply indebted to the faculty of the Dance Department at UC Riverside, including Linda Tomko, Priya Srinivasan, Jens Richard Giersdorf, Wendy Rogers, Imani Kai Johnson, visiting professor Ann Carlson, Joel Smith, José Reynoso, Taisha Paggett, and Luis Lara Malvacías. Their teaching and research modeled for me what it means to be a scholar and human of rigorous integrity and generosity. I am also grateful to the professors at my undergraduate institution, who opened my eyes to the exciting world of critical dance studies: Ananya Chatterjea, Diyah Larasati, Carl Flink, Toni Pierce-Sands, Maija Brown, and rest of U of MN dance department, thank you. I thank the faculty (especially Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebekah Kowal) and participants in the 2015 Mellon Summer Seminar Dance Studies in/and the Humanities, who helped me begin to feel at home in our academic community. -

Forum Group Fitness Classes

WILSON’S FITNESS CENTERS FORUM GROUP FITNESS CLASSES FALL SCHEDULE EFFECTIVE SEPTEMBER 9, 2019 TIME CLASS INSTRUCTOR STUDIO MONDAY 5:30 - 6:30 am BodyPump Lisa Kent Group 5:30 - 6:30 am Flight & Flexibility* Shelby Miller Cycling/Mind Body 7:00 - 8:00 am Aqua Peggy Nigh Pool 8:15 - 9:00 am Forever Fit Phyllis Koepp Group 8:25 - 9:25 am BodyFlow Angela Peterson Mind Body 9:00 - 9:45 am RPM✪ Betty Bohon Cycling 9:05 - 10:00 am Cardio Step Fran Welek Group 9:30 - 10:45 am Extreme H2O Lisa Glass Pool 9:35 - 10:30 am Barre Fitness* Becky Nielsen Mind Body 10:05 - 11:00 am Total Body Workout (TBW) Keira Hamann Group 12:00 - 12:45 pm BodyPump Express Amy Appold Group 4:30 - 5:25 pm Barre Fitness* HH Becky Nielsen Mind Body 5:30 - 6:30 pm Total Body Workout (TBW) Brenda Brown Group 5:30 - 6:30 pm Vinyasa Flow Yoga Susan Zeng Mind Body 5:40 - 6:25 pm RPM✪ Katy Lohmann Cycling 5:45 - 6:45 pm Aqua Blast Jennifer Mantle Pool 6:35 - 7:35 pm Aerial Yoga* Megan Carter Mind Body 6:40 - 7:25 pm Flight* Angela Peterson Cycling 7:30 - 8:00 pm GRIT Mimi Hamling Group 7:40 - 8:40 pm Prenatal/Postpartum Yoga* Megan Carter Mind Body TUESDAY 5:30 - 6:15 am BodyStep Express Katie Benfatto Group 5:30 - 6:30 am RPM✪ Betty Bohon Cycling 5:30 - 6:30 am BodyFlow Lisa Kent Mind Body 7:00 - 8:00 am Aqua Peggy Nigh Pool 8:25 - 9:25 am Yoga Linda Keown Group 8:30 - 9:15 am Chair Yoga* Erica Canlas Mind Body 9:00 - 9:30 am HIIT Flight* Travis Ritter Cycling 9:30 - 10:30 am Aqua Core & More Carey Henson Pool 9:30 - 10:15 am Pilates* Erica Canlas Mind Body 9:30 - 10:30 am -

Yoga Therapy

Yoga Therapy Yoga Therapy: Theory and Practice is a vital guidebook for any clinician or scholar looking to integrate yoga into the medical and mental health fields. Chapters are written by expert yoga therapy practitioners and offer theoretical, historical, and practice-based instruction on cutting-edge topics such as the application of yoga therapy to anger management and the intersection of yoga therapy and epigenetics; many chapters also include Q&A “self-inquiries.” Readers will find that Yoga Therapy is the perfect guide for practitioners looking for new techniques as well as those hoping to begin from scratch with yoga therapy. Ellen G. Horovitz, PhD, is professor and director of the graduate art therapy program at Nazareth College in Rochester, New York. She is the author of seven books, served on the American Art Therapy Association’s board of directors and as president-elect, and is past media editor of Arts & Health: An International Journal of Research, Policy and Practice. Staffan Elgelid, PhD, is an associate professor of physical therapy at Nazareth College in Rochester, New York and has served on the board of the North America Feldenkrais Guild, the advisory board of the International Association of Yoga Therapists, and on the editorial board of several journals. This page intentionally left blank Yoga Therapy: Theory and Practice Edited by Ellen G. Horovitz and Staffan Elgelid First published 2015 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge 27 Church Road, Hove, East Sussex BN3 2FA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2015 Ellen G. -

We Are the Yoga Life Studio

07780 535134 @yogalifestudio [email protected] www.yoga-life.co.uk @theyogalifestudio “Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness that most frightens us. We ask ourselves, 'Who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, fabulous?' Actually, who are you not to be? You are a child of God. Your playing small does not serve the world. There is nothing enlightened about shrinking so that other people won't feel insecure around you. We are all meant to shine, as children do. We were born to make manifest the glory of God that is within us. It's not just in some of us; it's in everyone. And as we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same. As we are liberated from our own fear, our presence automatically liberates others.” ― Marianne Williamson 2 About Us Welcome To Yoga Life Studio Our award winning Yoga Life Studio offers a wonderful variety of classes throughout the day to suit everyone. We are open 7 days a week, morning till evening. Unique and exclusive workshops as well as courses are available during the week and weekends. Our aim is to create a friendly space where everyone can enjoy their own practice in a safe and calm environment. Our friendly Yoga classes focus on removing stress, restoring balance and harmony in body, mind and spirit. The Yoga classes on offer involve practising traditional asanas, as well as combining breath awareness exercises with relaxation and meditation. -

Exploring Krishnamacharya's Ashtanga

Exploring Krishnamacharya’s Ashtanga based on the works of the Mysore years Yoga Makaranda (1934) Yogasanagalu (1941) and the 1938 documentary New blog mission statement. ............................................................................................ 4 Yogasanagalu's (1941) 'Original' Ashtanga Primary Group/ Series in Yoga Makaranda (1934) .............................................................................................................................. 6 How to practice Krishnamacharya's 'Original' Ashtanga Yoga ......................................... 11 Uddiyana kriya and asana in Krishnamacharya's 'Original' Ashtanga ............................. 17 Krishnamacharya's Yoga Makaranda extended stays. ..................................................... 20 Examples of usage of Kumbhaka (Breath retention) in asana in Krishnamacharya's Yoga Makaranda ..................................................................................................................... 24 Why did Krishnamacharya introduce kumbhaka (breath retention) into the practice of asana in Ashtanga? ........................................................................................................ 31 Why did Krishnamacharya introduced kumbhaka into asana? ........................................ 35 APPENDIX: Kumbhaka in Krishnamacharya's descriptions of asana ............................. 39 Krishnamacharya's asana description in Yogasanagalu (1941) ....................................... 45 Krishnamacharya's Yogasanagalu - the extra asana -

Ashtanga Yoga: Practice and Philosophy

Praise for Ashtanga Yoga: Practice and Philosophy “I love Ashtanga Yoga: Practice and Philosophy. At last there is a book that is not just on asana but coupled with that, the real beauty of asana and philosophy.” — Frances Liotta, founder of Yogamat “Gregor Maehle’s Ashtanga Yoga: Practice and Philosophy weaves philosophy and integrated knowledge of anatomy into our yoga practice to keep us centered in the heart of a profound tradition. He also gives us a brilliant translation and com- mentary on the Yoga Sutra, revealing a deep philosophical and historical context in which to ground and stimulate our entire lives.” — Richard Freeman, founder of the Yoga Workshop in Boulder, Colorado, and author of The Yoga Matrix CD “A much-needed new tool for practicing the method with greater safety in the physical form and with much needed depth in the inner form of the practice. I especially appreciate the comprehensive approach, which includes philosophical perspectives, anatomy, vedic lore, a thorough description of the physical method itself as well as a complete copy of Patanjala Yoga Darshana. A valuable contribution to the evolving understanding of this profound system and method of yoga.” — Chuck Miller, Ashtanga yoga teacher, senior student of Sri K. Pattabhi Jois since 1980 ii ASHTANGA YOGA Practice and Philosophy ASHTANGA YOGA Practice and Philosophy A Comprehensive Description of the Primary Series of Ashtanga Yoga, Following the Traditional Vinyasa Count, and an Authentic Explanation of the Yoga Sutra of Patanjali Gregor Maehle New World Library Novato, California New World Library 14 Pamaron Way Novato, California 94949 Copyright © 2006 by Gregor Maehle All rights reserved. -

Group Exercise Schedule Asheville Ymca Winter 2019 | February

COMBINATION (CARDIO + DANCE MIND / BODY / FLEXIBILITY STRENGTH) Hip Hop Fitness A dance-based cardio and toning Flex and Stretch A combination of gentle toning Athletic Conditioning Intense cardio, strength, program that blends various hip hop and dancehall and stretching exercises, concentrating on core muscles balance, and plyometric drills, along with core work moves to strengthen the core and lower body. Dip, and improving flexibility. This class is great for designed to improve performance in athletics as well as shake, and pump your body to the hottest hits while participants with joint and mobility limitations. everyday activities. Functional fitness at its best, getting fit and having fun! Pilates This conditioning program incorporates core Athletic Conditioning is sure to challenge all who Zumba® Latin-inspired dance class incorporating training, stretching, and proper breathing techniques for participate. international and pop music for a dynamic, exciting, and a full body workout. *Note: Please talk to your instructor Low Impact Fitness Geared towards active older effective workout. before class if you have osteopenia or osteoporosis. adults this low impact class can be performed seated or Soul Sweat™ an exhilarating dance fitness class, Gentle Yoga/Therapeutic Yoga A class with standing. Includes cardio, strength and flexibility. offering a joyful variety of music and dance styles. With a more gentle approach to yoga. Class will work through Early Bird Get your body moving first thing in the attainable choreography and heart expanding moves, a series of gentle postures with a focus on breathing morning with this low-impact cardio step routine this class is an invitation to have fun while digging techniques. -

Well & Being Spa Fitness Schedule July

OCTOBER–DECEMBER FITNESS CLASSES MONDAY FRIDAY 7:30AM TRX Fusion AT Debbie 7:00AM WellFit Circuit FS Autumn 8:00AM Yoga Fusion FS Susan 8:00AM Deep Yoga Stretch AT Rasoul 9:30AM Aqua Fitness SB Debbie 9:00AM Mat Pilates FS Rasoul 10:30AM Pilates HIIT FS Autumn 9:30AM Aqua Fitness SB Autumn 11:45AM Bootcamp FS Autumn 10:00AM Aerial Yoga* FS Rachel 5:45PM WellFit Circuit FS Vera 11:00AM Cardio Dance FS Autumn TUESDAY SATURDAY 7:00AM Morning Yoga Flow AT Leanna 7:00AM Spin FS Debbie 7:30AM Body Sculpt 30 MIN FS Vera 8:00AM Hatha Yoga AT Stacy 8:00AM Spin FS Vera 8:00AM Strength Training FS Debbie 9:00AM Core & Stretch FS Debbie 9:00AM Aerial Yoga* AT Debbie 10:00AM Aerial Yoga AT Debbie 10:00AM Aerial Yoga* AT Debbie 10:30AM Barre BURN FS Staff 6:00PM Yin Yoga FS Susan SUNDAY WEDNESDAY 8:00AM Wall Yoga MB Rasoul 8:00AM Gentle Yoga AT Gloria 7:30AM TRX Fusion AT Debbie 9:00AM Yoga Nidra 30 MIN AT Gloria 8:00AM Yoga Fusion FS Susan 9:00AM Surfset Fitness FS Abdelhak 9:30AM Aqua Fitness SB Debbie 10:00AM Aerial Yoga* AT Abdelhak 10:30AM Pilates HIIT FS Autumn 4:30PM Restorative Yoga FS Rachel 11:45AM Bootcamp FS Autumn 5:45PM WellFit Circuit FS Vera THURSDAY LOCATION KEY: AT ATRIUM MB MIND/BODY 7:00AM Morning Yoga Flow AT Leanna FS FITNESS STUDIO 7:00AM Body Sculpt 30 MIN FS Debbie SB SUNSET BEACH & OVERLOOK 7:30AM Spin FS Vera SP SPA ROOFTOP POOL 8:30AM Cardio Dance FS Debbie FITNESS ON DEMAND 9:30AM Aerial Yoga* AT Debbie 10:30AM Barre BURN FS Staff 60 MIN Personal Training Sessions available for $89, and 30 MIN Assisted Stretch available for $75. -

Yoga Class Descriptions

HEALI NG C E NTRE YOGA CLASS DESCRIPTIONS 1 YOGA CLASS DESCRIPTIONS AERIAL YOGA Aerial yoga combines acrobatic arts and anti-gravity asana, but it’s also an accessible practice that can help you find more length in your spine and safe alignment in your poses. The positions you can achieve in Aerial Yoga also temporarily improve circulation. This can bring you focus and improved energy as well as a boost in mood. GENTLE AWAKENING YOGA Gentle Awakening yoga is a gentle, introspective class that restores mind, body, and spirit. Incorporating twists and slow fully embodied movements this class stimulates the digestive, immune, and lymph systems, while allowing students to focus on deep, healthful breathing. Gentle Awakening yoga is a wonderful practice for anyone interested in improving or maintaining good health. HATHA YOGA Hatha simply refers to the practice of physical yoga postures, meaning Ashtanga, vinyasa, Iyengar, and even power yoga classes are all Hatha Yoga. The word “hatha” can be translated two ways: as “willful” or the yoga of activity, and as “sun” (ha) and “moon” (tha), the yoga of balance. Hatha practices are designed to align and calm your body, mind, and spirit in preparation for meditation. Hatha classes are slower-paced and there’s an emphasis on static postures. This makes Hatha Yoga a good place to work on alignment, learn relaxation techniques, and become comfortable with doing yoga while building strength and flexibility. Some classes may include Pranayama (yogic breathing techniques) and meditation. RESTORATIVE YOGA Restorative yoga classes are very mellow. The practice focuses on slowing down, opening your body through passive stretching, and cultivating inner stillness. -

Die Energetische Anatomie Des Hatha Yoga

BI_978-3-426-67581-6_s001-137.indd 2 08.08.19 11:11 Wanda Badwal YOGADie 108 wichtigsten Übungen und ihre ganzheitliche Wirkung Mit Fotos von Dirk Spath Photography BI_978-3-426-67581-6_s001-137.indd 3 08.08.19 11:11 Die vorliegenden Informationen beruhen auf gründlicher Recherche der Autorin. Alle Empfehlungen und Informationen sind von Autorin und Verlag sorgfältig geprüft, dennoch kann keine Garantie für das Ergebnis übernommen werden. Jegliche Haftung der Autorin bzw. des Verlags und seiner Beauftragten für Gesund- heitsschäden sowie Personen-, Sach- oder Vermögensschäden ist ausgeschlossen. Der Leser sollte in jedem Fall die Anwendung der hier genannten Methoden und Übungen auf seinen speziellen Bedarfsfall vom betreuenden Arzt prüfen lassen. Besuchen Sie uns im Internet: www.knaur-balance.de Originalausgabe 2019 © 2019 Wanda Badwal © 2019 Knaur Verlag Ein Imprint der Verlagsgruppe Droemer Knaur GmbH & Co. KG, München Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk darf – auch teilweise – nur mit Genehmigung des Verlags wiedergegeben werden. Redaktion: Anke Schenker Covergestaltung: PixxWerk® München unter Verwendung von Motiven von shutterstock.com Coverabbildung: Dirk Spath Abbildungen im Innenteil: alle Fotos von Dirk Spath, außer: Shutterstock.com: S. 5, 9, 22, 34, 41, 287, 288, 303, 304 und Schmuckelemente iStock / Getty Images: S. 31 / Sudowoodo, S. 53 / goshdarnypooh Marcel Peters: S. 11, 33, 304 Lisa Hantke Photography (www.lisahantke.de): S. 40 Tom Schlegel / Spray’n Pray Productions: S. 54, 244 Hanna Witte Fotografie (www.hanna-witte.de): -

Specialty Group Fitness Classes Fall 2019

WILSON’S FITNESS CENTERS SPECIALTY CLASSES FALL SCHEDULE EFFECTIVE SEPTEMBER 9, 2019 TIME CLASS INSTRUCTOR STUDIO MONDAY 5:00 - 6:00 am Boxing/Kickboxing* Nikki Wilson MAC Group 5:15 - 6:00 am Hot Barre* Cassie Kauffman Forum Hot 5:30 - 6:30 am Flight & Flexibility* Shelby Miller Forum Cycling/Mind Body 9:15 - 10:15 am Fusion Hot 60* Janette Keller Forum Hot 9:35 - 10:30 am Barre Fitness* Becky Nielsen Forum Mind Body 12:00 - 12: 45pm Hot Barre* Candace Kauffman Forum Hot 12:00 - 1:00 pm Boxing/Kickboxing* Nikki Wilson MAC Group 12:30 - 1:15 pm Animal Flow Circuit* HH Malcolm Castilow District Group/Hot 4:15 - 5:15 pm Fusion Hot 60* HH Hayes Murray Forum Hot 4:05 - 4:35 pm Animal Flow* HH Meghan McCullah Rangeline Mind Body 4:30 - 5:25 pm Barre Fitness* HH Becky Nielsen Forum Mind Body 5:30 - 6:15 pm Hot Barre* Robin May Forum Hot 5:30 - 6:30 pm Aerial Fabric Skills Level 1* Wendy Batson Rangeline Mind Body 6:30 - 7:30 pm Radiant Yoga* Shelby Miller Forum Hot 6:35 - 7:35 pm Introduction to Aerial Fabrics* Wendy Batson Rangeline Mind Body 6:35 - 7:35 pm Aerial Yoga* Megan Carter Forum Mind Body 7:40 - 8:40 pm Prenatal/Postpartum Yoga* Megan Carter Forum Mind Body TUESDAY 5:30 - 6:30 am Fusion Hot 60* Shelby Miller Forum Hot 7:00 - 7:45 am Pilates* HH Erin Jensen Rangeline Mind Body 8:30 - 9:15 am Chair Yoga* Erica Canlas Forum Mind Body 9:00 - 9:30 am HIIT Flight* Travis Ritter Forum Cycling 9:15 - 10:00 am Hot Barre* Catina Topash Forum Hot 9:30 - 10:15 am Pilates* Erica Canlas Forum Mind Body 10:15 - 11:15 am Radiant Yoga* Catina Topash