Open Streets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Itinerari Di Architettura Milanese

ORDINE DEGLI ARCHITETTI, FONDAZIONE DELL’ORDINE DEGLI ARCHITETTI, PIANIFICATORI, PAESAGGISTI E CONSERVATORI PIANIFICATORI, PAESAGGISTI E CONSERVATORI DELLA PROVINCIA DI MILANO DELLA PROVINCIA DI MILANO /figure ritratti dal professionismo milanese Piero Bottoni: la dimensione civile della bellezza Giancarlo Consonni Graziella Tonon Itinerari di architettura milanese L’architettura moderna come descrizione della città “Itinerari di architettura milanese: l’architettura moderna come descrizione della città” è un progetto dell’Ordine degli Architetti P.P.C. della Provincia di Milano a cura della sua Fondazione. Coordinamento scientifico: Maurizio Carones Consigliere delegato: Paolo Brambilla Responsabili della redazione: Alessandro Sartori, Stefano Suriano Coordinamento attività: Giulia Pellegrino Ufficio Stampa: Ferdinando Crespi “Piero Bottoni: la dimensione civile della bellezza” Giancarlo Consonni, Graziella Tonon a cura di: Alessandro Sartori, Stefano Suriano, Barbara Palazzi Per le immagini si ringrazia: Archivio Piero Bottoni in quarta di copertina: Piero Bottoni, Schizzo di studio per il Padiglione mostre al QT8, 1951 La Fondazione dell’Ordine degli Architetti P.P.C. della Provincia di Milano rimane a disposizione per eventuali diritti sui materiali iconografici non identificati www.ordinearchitetti.mi.it www.fondazione.ordinearchitetti.mi.it Piero Bottoni: la dimensione civile della bellezza Nei quarant’anni centrali del XX secolo la vicenda di Piero Bottoni si intreccia con la storia di Milano. Chi si occupi delle trasformazioni -

Milan, Italy Faculty Led Learning Abroad Program Fashion and Design Retailing: the Italian Way Led By: Dr

Milan, Italy Faculty Led Learning Abroad Program Fashion and Design Retailing: The Italian Way Led by: Dr. Chiara Colombi & Dr. Marcella Norwood What: 10-Day Study Tour: Milan, Italy (including Florence, Italy) When: Dates: May 22 – 31, 2016 (Between spring and summer terms 2016) Academic Plan: 1. Participate in preparation series during spring 2016 2. Travel & tour 3. Complete written assignments Enrollment: Enroll in HDCS 4398 or GRET 6398 (summer mini session) GPA Requirement: 2.5 (undergraduates); 3.0 (graduates) Scholarships: UH International Education Fee Scholarships 1. $750 (see http://www.uh.edu/learningabroad/scholarships/uh- scholarships/ for eligibility and application details. (graduate students already receiving GTF not eligible for scholarship) Deadline: IEF scholarship applications open January 4, close March 4. http://www.uh.edu/learningabroad/scholarships/uh-scholarships/) 2. $250 tuition rebate for HDCS 4398 (see http://www.uh.edu/learningabroad/scholarships/uh-scholarships/) (not available for GRET 6398 enrollment) To Apply: For Study Tour: To go into the registration, please click on this link (www.worldstridescapstone.org/register ) and you will be taken to the main registration web page. You will then be prompted to enter the University of Houston’s Trip ID: 129687 . Once you enter the Trip ID and requested security characters, click on the ‘Register Now’ box below and you will be taken directly to the site . Review the summary page and click ‘Register’ in the top right corner to enter your information 1 . Note: You are required to accept WorldStrides Capstone programs terms and conditions and click “check-out” before your registration is complete. -

Welcome to Milan

WELCOME TO MILAN WHAT MILAN IS ALL ABOUT MEGLIOMILANO MEGLIOMILANO The brochure WELCOME TO MILAN marks the attention paid to those who come to Milan either for business or for study. A fi rst welcome approach which helps to improve the image of the city perceived from outside and to describe the city in all its various aspects. The brochure takes the visitor to the historical, cultural and artistic heritage of the city and indicates the services and opportunities off ered in a vivid and dynamic context as is the case of Milan. MeglioMilano, which is deeply involved in the “hosting fi eld” as from its birth in 1987, off ers this brochure to the city and its visitors thanks to the attention and the contribution of important Institutions at a local level, but not only: Edison SpA, Expo CTS and Politecnico of Milan. The cooperation between the public and private sectors underlines the fact that the city is ever more aiming at off ering better and useable services in order to improve the quality of life in the city for its inhabitants and visitors. Wishing that WELCOME TO MILAN may be a good travel companion during your stay in Milan, I thank all the readers. Marco Bono Chairman This brochure has been prepared by MeglioMilano, a non-profi t- making association set up by Automobile Club Milan, Chamber of Commerce and the Union of Commerce, along with the Universities Bocconi, Cattolica, Politecnico, Statale, the scope being to improve the quality of life in the city. Milan Bicocca University, IULM University and companies of diff erent sectors have subsequently joined. -

Milan Dynamic Noise Mapping from Few Monitoring Stations: Statistical Analysis on Road Network

INTER-NOISE 2016 Milan dynamic noise mapping from few monitoring stations: statistical analysis on road network Giovanni ZAMBON1; Roberto BENOCCI2; Alessandro BISCEGLIE3; H. Eduardo ROMAN4 1-2-3 Dipartimento di Scienze dell’Ambiente e del Territorio e di Scienze della Terra, University of Milano - Bicocca, Italy 4 Dipartimento di Fisica “G. Occhialini”, Università degli Studi di Milano–Bicocca, Milan, Italy ABSTRACT One of the main objectives of "Dynamap" project is to realize a dynamic noise map within a given area of the city of Milan, containing about 2000 road arches, by using approximately 20 continuous measuring stations. This map is scheduled to be updated dynamically within a period of time varying from 5 minutes to 1 hour. The ability to obtain reliable maps within a complex urban context is linked to the fact that the vehicle flow patterns are very regular. In the first phase of the project, we monitored nearly 100 roads for a period of at least 24 hours. Then, these roads have been aggregated by means of a cluster analysis, depending on their noise level profiles. The analysis of the distribution of a non-acoustical parameter in the clusters, such as the vehicular flow rate, allowed to attribute a specific noise profile to a road not present in the database. It was also possible to select the most representative arches, among the 2000 arches to be mapped, where the monitoring stations will be installed. It was finally estimated the error associated with the noise levels of the dynamic maps as a function of the updating time interval. -

Orari E Percorsi Della Linea Metro M1

Orari e mappe della linea metro M1 Sesto F.S. - Rho Fiera / Bisceglie Visualizza In Una Pagina Web La linea metro M1 (Sesto F.S. - Rho Fiera / Bisceglie) ha 2 percorsi. Durante la settimana è operativa: (1) Rho Fiera/Bisceglie: 00:03 - 23:54 (2) Sesto F.S.: 00:11 - 23:57 Usa Moovit per trovare le fermate della linea metro M1 più vicine a te e scoprire quando passerà il prossimo mezzo della linea metro M1 Direzione: Rho Fiera/Bisceglie Orari della linea metro M1 31 fermate Orari di partenza verso Rho Fiera/Bisceglie: VISUALIZZA GLI ORARI DELLA LINEA lunedì 00:03 - 23:54 martedì 00:03 - 23:54 Sesto 1° Maggio FS 269 Viale Antonio Gramsci, Cinisello Balsamo mercoledì 00:03 - 23:54 Sesto Rondò giovedì 00:03 - 23:54 Piazza 4 Novembre, Cinisello Balsamo venerdì 00:03 - 23:54 Sesto Marelli sabato 00:03 - 23:54 Viale Tommaso Edison, Milano domenica 00:03 - 23:54 Villa S.G. 315 Viale Monza, Milano Precotto 220 Viale Monza, Milano Informazioni sulla linea metro M1 Direzione: Rho Fiera/Bisceglie Gorla Fermate: 31 158 Viale Monza, Milano Durata del tragitto: 37 min La linea in sintesi: Sesto 1° Maggio FS, Sesto Rondò, Turro Sesto Marelli, Villa S.G., Precotto, Gorla, Turro, 116 Viale Monza, Milano Rovereto, Pasteur, Loreto, Lima, P.ta Venezia, Palestro, San Babila, Duomo, Cordusio, Cairoli, Rovereto Cadorna FN, Conciliazione, Pagano, Buonarroti, 93 Viale Monza, Milano Amendola, Lotto, Qt8, Lampugnano, Uruguay, Bonola, S. Leonardo, Molino Dorino, Pero, Rho Fiera Pasteur Viale Monza, Milano Loreto Corso Buenos Aires, Milano Lima 1 Piazza Lima, Milano P.ta Venezia 1 Corso Buenos Aires, Milano Palestro 53 Corso Venezia, Milano San Babila 4 Piazza San Babila, Milano Duomo Cordusio Piazza Cordusio, Milano Cairoli Largo Cairoli, Milano Cadorna FN Piazzale Luigi Cadorna, Milano Conciliazione Piazza della Conciliazione, Milano Pagano Via Giorgio Pallavicino, Milano Buonarroti Piazza Michelangelo Buonarroti, Milano Amendola 5 Piazza Giovanni Amendola, Milano Lotto Piazzale Lorenzo Lotto, Milano Qt8 Piazza Santa Maria Nascente, Milano Lampugnano Uruguay Bonola S. -

Milan and the Lakes Travel Guide

MILAN AND THE LAKES TRAVEL GUIDE Made by dk. 04. November 2009 PERSONAL GUIDES POWERED BY traveldk.com 1 Top 10 Attractions Milan and the Lakes Travel Guide Leonardo’s Last Supper The Last Supper , Leonardo da Vinci’s 1495–7 masterpiece, is a touchstone of Renaissance painting. Since the day it was finished, art students have journeyed to Milan to view the work, which takes up a refectory wall in a Dominican convent next to the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie. The 20th-century writer Aldous Huxley called it “the saddest work of art in the world”: he was referring not to the impact of the scene – the moment when Christ tells his disciples “one of you will betray me” – but to the fresco’s state of deterioration. More on Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) Crucifixion on Opposite Wall Top 10 Features 9 Most people spend so much time gazing at the Last Groupings Supper that they never notice the 1495 fresco by Donato 1 Leonardo was at the time studying the effects of Montorfano on the opposite wall, still rich with colour sound and physical waves. The groups of figures reflect and vivid detail. the triangular Trinity concept (with Jesus at the centre) as well as the effect of a metaphysical shock wave, Example of Ageing emanating out from Jesus and reflecting back from the 10 Montorfano’s Crucifixion was painted in true buon walls as he reveals there is a traitor in their midst. fresco , but the now barely visible kneeling figures to the sides were added later on dry plaster – the same method “Halo” of Jesus Leonardo used. -

Our Residences How to Reach Us TURRO Turro Is Part of the Camplus Living Network, Which Means by Car Hospitality and Functionality at a Good Quality-Price Ratio

Our residences How to reach us TURRO Turro is part of the Camplus Living network, which means By car hospitality and functionality at a good quality-price ratio. From the East ring road, take exit number 10 Via Palmanova. Drive along A wide range of services makes each of the residences the fl yover Cascina Gobba and then via Palmanova. Turn right in via San unique and adequate to satisfy all of your needs. Camplus Giovanni de la Salle, then turn left in Via Padova. Turn again right in via Living combines tradition and modernity creating, in 8 of Francesco Cavezzali, and drive as far as 25, via Stamira D’Ancona. the richest Italian cities as to history and culture, a perfect By train blend of past and present: places for welcoming which can From the Central railway station, catch metro line number 2 (green) towards Cascina Gobba, get off at Loreto, catch metro line number 1 make your stay even more pleasant. (red) towards Sesto FS, get off at Turro. A place for welcome By plane Bologna Parma Torino From Linate Airport Catania Milano Venezia - A51 motorway, or East ring road, exit number 10 Via Palmanova - Bus number 73, get off at San Babila. Metro line 1 (red) towards Sesto Ferrara Roma FS, get off at Turro. - Shuttle bus towards the central railway station, then metro line 2 (green) towards Cascina Gobba, get off at Loreto, metro line 1 (red) towards Sesto FS, get off at Turro. From Malpensa Airport - Shuttle bus towards the central railway station, then metro line 2 (green) towards Cascina Gobba, get off at Loreto, metro line 1 (red) towards Sesto FS, get off at Turro. -

For an Urban History of Milan, Italy: the Role Of

FOR AN URBAN HISTORY OF MILAN, ITALY: THE ROLE OF GISCIENCE DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of Texas State University‐San Marcos in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of PHILOSOPHY by Michele Tucci, B.S., M.S. San Marcos, Texas May 2011 FOR AN URBAN HISTORY OF MILAN, ITALY: THE ROLE OF GISCIENCE Committee Members Approved: ________________________________ Alberto Giordano ________________________________ Sven Fuhrmann ________________________________ Yongmei Lu ________________________________ Rocco W. Ronza Approved: ______________________________________ J. Micheal Willoughby Dean of the Gradute Collage COPYRIGHT by Michele Tucci 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincere thanks go to all those people who spent their time and effort to help me complete my studies. My dissertation committee at Texas State University‐San Marcos: Dr. Yongmei Lu who, as a professor first and as a researcher in a project we worked together then, improved and stimulated my knowledge and understanding of quantitative analysis; Dr. Sven Fuhrmann who, in many occasions, transmitted me his passion about cartography, computer cartography and geovisualization; Dr. Rocco W. Ronza who provided keen insight into my topic and valuable suggestions about historical literature; and especially Dr. Alberto Giordano, my dissertation advisor, who, with patience and determination, walked me through this process and taught me the real essence of conducting scientific research. Additional thanks are extended to several members of the stuff at the Geography Department at Texas State University‐San Marcos: Allison Glass‐Smith, Angelika Wahl and Pat Hell‐Jones whose precious suggestions and help in solving bureaucratic issues was fundamental to complete the program. My office mates Matthew Connolly and Christi Townsend for their cathartic function in listening and sharing both good thought and sometimes frustrations of being a doctoral student. -

ITALY. Milano. December 9, 2010. Via Leoncavallo. ITALY. Milan

ITALY. Milano. ITALY. Milan. December 9, 2010. Via September 11, 2015. Leoncavallo. Porta Genova. People attending the pro-refugees barefoot ITALY. Milan, 2010. march from Porta Chinatown. Genova to the Porta Ticinese dock known as Darsena. The main march was on the same ITALY. Milan. March day in Venice, born 2, 2014. from an idea by the The UniCredit Tower Italian movie seen from Cavalcavia director Daniele Eugenio Bussa. It is Segre, during the part of "Progetto annual Venice Film Porta Nuova"-Porta Festival; more Nuova Project-a plan barefoot marches took of urban renewal and place in several development after a Italian cities on the long period of decay, same day. which involves Isola, Varesine and ITALY. Milan, 2010. Garibaldi areas. Porta Genova. Qatar Investment Authorities is now the sole property owner of Milan Porta ITALY. MILAN. Nuova business February 23, 2011. district. JO NO FUI fashion show ad, in the ITALY. Milan. April tensile structure in 13, 2014. Piazza Duomo, on the Young people in Porta opening day of Milan Genova during the Fashion Week 2011. Design Week. ITALY. Milan, 2010. San Babila. ITALY. MILAN. ITALY. MILAN. May 1, February 25, 2011. 2010. Young people in Before Massimo Corso di Porta Rebecchi Fashion Show Ticinese at May Day at Palazzo Clerici rally. during Milan Fashion Week 2011. ITALY. MILAN. February 23, 2011. Fashion designer Fausto Puglisi (on the left,looking at the computer) and fashion bloggers in Via della Spiga, during Milan Fashion Week 2011. ITALY. MILAN. March 1, 2011. Backstage at Circolo Filologico during Milan Fashion Week 2011. -

Impagin 9 Zone

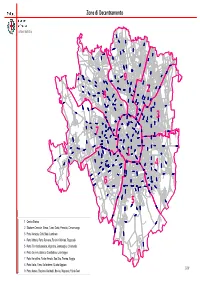

Zone di Decentramento Settore Statistica V i a C o m a s i n a V ia V l i e a R u G b . ic o P n a e s t a i t s e T . F e l a i V ani V gn i odi a ta M . Lit L A . Via V ia O l r e n E a . t F o e r V m i a i A s t e s a a n z i n orett i Am o Via C. M e l a i V V V i i a V a i B a M G o . v . L i B s . e a a G s s r s c d a o e s a r n s B i a . F ia V i t s e T V . V F i a a v i ado a l e P l ia e V P a i e E l . V l e F g e r r i n m o i V ia R o M s am s b i r et ti Piazza dell'Ospedale Maggiore a a v z o n n a o lm M a P e l ia a i V V a v Via V o G i d all a a ara ni P te B ia a o nd i a V v . C i G s ia V a V ia s A c a p a e l p i e C n n a in i i V V ia G al V V lar i i at ia hini a e V mbrusc Piazza h V i Via La C c V a r i a C Bausan . -

INFOPACK Final

! ! Welcome to ! In this document you will find information about: • The hotel • The conference venues o Centro culturale il Pertini o BASE o ANCI Lombardia – La Casa dei Comuni • Travels o From the airports to the hotel o From the airports to the conference venues o From the hotel to the conference venues If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact us! ! [email protected] +39 02 66023.201/804/887 +39 347 0490966 +39 338 5080748 #youthwork16 ! THE HOTEL, B&B MILANO - SESTO ! Name: B&B Hotel Milano Sesto Address: Via Ercole Marelli 303, Sesto San Giovanni (Mi) Phone: +39 02.22471152 Web: http://www.hotel-bb.com/it/hotel/milano-sesto.htm ! ! ! ! Information about the conference venues ! Centro culturale Il Pertini Monday 17 October in Cinisello Balsamo Name: Centro culturale il Pertini Address: Piazza Natale Confalonieri 3, 20092, Cinisello Balsamo (Mi) Phone: +39. 02.66023542 Web: http://www.comune.cinisello-balsamo.mi.it/spip.php?rubrique2324 www.ilpertini.it www.facebook.com/ilpertini ! ! ! ! ! BASE a place for cultural progress Tuesday 18 October in Milano: Name: BASE Address:Via Bergognone 34, 20144, Milano www.base.milano.it www.facebook.com/BASE-Milano-1618538701746097 twitter.com/base_milano www.instagram.com/base_milano ! ! ! ! ! ANCI Lombardia - La Casa dei Comuni ! Wednesday 19 October in Milano: Name: ANCI Lombardia – La Casa dei Comuni Address: Via Rovello 2, 20121, Milano Phone: +39. 02.72629601 Web: www.ancilab.it www.anci.lombardia.it ! ! ! ! Information about travels From the airports to the hotel: From Linate Airport to the Hotel ! In front of the main exit of the airport, take bus Nr. -

Hostelworld Guide for Milan the Essentials Climate

Hostelworld Guide for Milan The Essentials Climate Getting There As it is one of Italy's most northerly cities, Milan experiences cooler temperatures than most of its counterparts. Winters frequently experience By plane: Milan is served by three airports - Linate, temperatures of 0°C and sometimes even lower. Malpensa and Orio al Serio. Some budget airlines Temperatures begin to climb in mid-April and by use Orio al Serio and Malpensa, while Linate is summer Milan experiences countless trademark hot nearest to central Milan. All are connected to the days Italy is so synonymous with. September is city centre via bus. extremely mild before things start to cool down again in October. By train: Milan's Stazione Centrale has rail links with all of Europe's major cities. It is a very imressive building and not far from the historical centre. By bus: Buses arriving from and going to major European cities do so from the bus station at Piazza Sigmund Freud. Getting Around On foot: Milan's historical centre is easily explored on foot, but to get from Stazione Centrale to Il Duomo you may want to utilise the metro. By metro: Milan's metro network consists of three Useful Information Slick, sleek and uber-cool, Milan is one of the most stylish cities in the world. Lavish designer stores lines - M1 (red), M2 (green) and M3 (yellow). It is abound endless streets while just as lavish bags loaded with the latest 'must-have' items hang from easy to use and efficient. Single journeys cost €1 Language: Italian endless shoppers' arms.