Canterbury Christ Church University's Repository of Research Outputs Http

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, a MATTER of LIFE and DEATH/ STAIRWAY to HEAVEN (1946, 104 Min)

December 8 (XXXI:15) Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH/ STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN (1946, 104 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger Music by Allan Gray Cinematography by Jack Cardiff Film Edited by Reginald Mills Camera Operator...Geoffrey Unsworth David Niven…Peter Carter Kim Hunter…June Robert Coote…Bob Kathleen Byron…An Angel Richard Attenborough…An English Pilot Bonar Colleano…An American Pilot Joan Maude…Chief Recorder Marius Goring…Conductor 71 Roger Livesey…Doctor Reeves Robert Atkins…The Vicar Bob Roberts…Dr. Gaertler Hour of Glory (1949), The Red Shoes (1948), Black Narcissus Edwin Max…Dr. Mc.Ewen (1947), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), 'I Know Where I'm Betty Potter…Mrs. Tucker Going!' (1945), A Canterbury Tale (1944), The Life and Death of Abraham Sofaer…The Judge Colonel Blimp (1943), One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), 49th Raymond Massey…Abraham Farlan Parallel (1941), The Thief of Bagdad (1940), Blackout (1940), The Robert Arden…GI Playing Bottom Lion Has Wings (1939), The Edge of the World (1937), Someday Robert Beatty…US Crewman (1935), Something Always Happens (1934), C.O.D. (1932), Hotel Tommy Duggan…Patrick Aloyusius Mahoney Splendide (1932) and My Friend the King (1932). Erik…Spaniel John Longden…Narrator of introduction Emeric Pressburger (b. December 5, 1902 in Miskolc, Austria- Hungary [now Hungary] —d. February 5, 1988, age 85, in Michael Powell (b. September 30, 1905 in Kent, England—d. Saxstead, Suffolk, England) won the 1943 Oscar for Best Writing, February 19, 1990, age 84, in Gloucestershire, England) was Original Story for 49th Parallel (1941) and was nominated the nominated with Emeric Pressburger for an Oscar in 1943 for Best same year for the Best Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Writing, Original Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Missing Missing (1942) which he shared with Michael Powell and 49th (1942). -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

Reading List for Atypically British: the Films of Powell and Pressburger

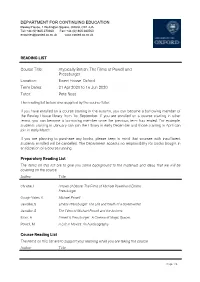

DEPARTMENT FOR CONTINUING EDUCATION Rewley House, 1 Wellington Square, Oxford, OX1 2JA Tel: +44 (0)1865 270360 Fax: +44 (0)1865 280760 [email protected] www.conted.ox.ac.uk READING LIST Course Title: Atypically British: The Films of Powell and Pressburger Location: Ewert House, Oxford Term Dates: 21 Apr 2020 to 16 Jun 2020 Tutor: Pete Boss The reading list below was supplied by the course tutor. If you have enrolled on a course starting in the autumn, you can become a borrowing member of the Rewley House library from 1st September. If you are enrolled on a course starting in other terms, you can become a borrowing member once the previous term has ended. For example, students starting in January can join the Library in early December and those starting in April can join in early March. If you are planning to purchase any books, please keep in mind that courses with insufficient students enrolled will be cancelled. The Department accepts no responsibility for books bought in anticipation of a course running. Preparatory Reading List The items on this list are to give you some background to the materials and ideas that we will be covering on the course. Author Title Christie, I Arrows of Desire: The Films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger Gough-Yates, K Michael Powell Jawolke, S Emeric Pressburger: The Life and Death of a Screenwriter Jawolke, S The Films of Michael Powell and the Archers Moor, A Powell & Pressburger : A Cinema of Magic Spaces Powell, M A Life in Movies: An Autobiography Course Reading List The items on this list are to support your learning while you are taking the course. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

Blind Spot: Hitler's Secretary

Blind Spot: Hitler’s Secretary Dir: Andre Heller and Othmar Schmiderer, Austria, 2003 A review by Jessica Lang, John Hopkins University, USA Blind Spot: Hitler's Secretary, a documentary film directed by Andre Heller and Othmar Schmiderer, is the first published account of Traudl Humps Junge's memories as Hitler's secretary from 1942 until his suicide in 1945. The ninety minute film, which came out in 2002, was edited from more than ten hours of footage. The result is a disturbing compilation of memories and reflections on those memories that, while interesting enough, are presented in a way that is at best uneven. Part of this unevenness is a product of the film's distribution of time: while it begins with Junge's recalling how she interviewed for her secretarial position in order to quit another less enjoyable job, most of it is spent reflecting on Hitler as his regime and military conquests collapsed around him. But the film also is not balanced in terms of its reflectivity, abandoning halfway through some of its most interesting and most important narrative strategies. In terms of its construction, the film involves Junge speaking directly to the camera. She speaks with little prompting (that the audience can hear, at least) and appears to have retained a footprint of war memories that has remained almost perfectly intact through the sixty years she has kept them largely to herself. Interrupted by sudden editing breaks, the viewer is rushed through the first two and a half years of Junge's employment in the first half of the film. -

HP0221 Teddy Darvas

BECTU History Project - Interview No. 221 [Copyright BECTU] Transcription Date: Interview Dates: 8 November 1991 Interviewer: John Legard Interviewee: Teddy Darvas, Editor Tape 1 Side A (Side 1) John Legard: Teddy, let us start with your early days. Can you tell us where you were born and who your parents were and perhaps a little about that part of your life? The beginning. Teddy Darvas: My father was a very poor Jewish boy who was the oldest of, I have forgotten how many brothers and sisters. His father, my grandfather, was a shoemaker or a cobbler who, I think, preferred being in the cafe having a drink and seeing friends. So he never had much money and my father was the one brilliant person who went to school and eventually to university. He won all the prizes at Gymnasium, which is the secondary school, like a grammar school. John Legard: Now, tell me, what part or the world are we talking about? Teddy Darvas: This is Budapest. He was born in Budapest and whenever he won any prizes which were gold sovereigns, all that money went on clothes and things for brothers and sisters. And it was in this Gymnasium that he met Alexander Korda who was in a parallel form. My father was standing for Student's Union and he found somebody was working against him and that turned out to be Alexander Korda, of course the family name was Kelner. They became the very, very greatest of friends. Alex was always known as Laci which is Ladislav really - I don't know why. -

Proud to Sponsor Canterbury Festival

CANTERBURY FESTIVAL KENT’S INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL 20 OCT - 3 NOV 2018 canterburyfestival.co.uk i Welcome & Sponsors Box Office: 01227 787787 canterburyfestival.co.uk WELCOME PARTNER AND PRINCIPAL SPONSOR FUNDERS from Rosie Turner Festival Director Per ardua ad astra (through struggle to the stars) has been our watchword in preparing this Canterbury Christ Church University welcomes the SPONSORS year’s star-studded Festival. opportunity to work with Canterbury Festival in 2018, for the ninth consecutive year. We are delighted to be Massive thanks to our sponsors and associated with such a prestigious and popular event in donors – led by Canterbury Christ the city, as both Principal Sponsor and Partner. Church University – who have stayed Venue Sponsor loyal, increased their commitment, Canterbury Festival plays both a vital role in the city’s or joined us for the first time, proving excellent cultural programme and the UK festival that Canterbury needs, loves and calendar. It brings together the people of Canterbury, deserves a fantastic Festival. Now visitors, and international artists in an annual celebration you can support us by booking early, of arts and culture, which contributes to a prosperous telling your friends, organising a and more vibrant city. This year’s Festival promises to work’s night out… we need to sell be as ambitious and inspirational as ever, with a rich Technical Sponsor more tickets than ever before and and varied programme. there’s lots to tempt you. The University is passionate about, and contributes From Knights and Dames to significantly to, the region’s creative economy. We are performing Socks – please look proud to work closely with a range of local and national through the entire programme as cultural organisations, such as the Canterbury Festival, some of our unique events defy to collectively offer an artistically vibrant, academically simple classification. -

Botany Bay on Talking Pictures TV Stars: Alan Ladd, James Mason and Patricia Medina

Talking Pictures TV www.talkingpicturestv.co.uk Highlights for week beginning SKY 328 | FREEVIEW 81 Mon 11th May 2020 FREESAT 306 | VIRGIN 445 Botany Bay on Talking Pictures TV Stars: Alan Ladd, James Mason and Patricia Medina. Directed by John Farrow, released in 1953. In 1787 prisoners are shipped from Newgate Jail on Charlotte to found a new penal colony in Botany Bay, New South Wales. Amongst them is an American medical student who was wrongly imprisoned. During the journey he clashes with the villainous Captain, and is soon plotting mutiny against him. Airs on Saturday 16th May at 9pm. Monday 11th May 1:10pm Tuesday 12th May 10pm The Importance of being Earnest The Best of Everything (1959) (1952) Drama, directed by Jean Negulesco. Comedy, directed by Anthony Stars: Joan Crawford, Louis Jourdan, Asquith. Stars: Michael Redgrave, Hope Lange, Stephen Boyd and Suzy Richard Wattis, Michael Denison, Parker. A story about the lives of three Edith Evans, Margaret Rutherford. women who share a small apartment Algernon discovers that his friend in New York City. Ernest has a fictional brother and Wednesday 13th May 11:30am decides to impersonate the brother. Scotland Yard Investigator (1945) Monday 11th May 5:30pm Directed by George Blair. Hue and Cry (1947) Stars: C. Aubrey Smith, Stephanie Adventure. Director: Charles Crichton. Bachelor, Erich von Stroheim. During Stars: Alastair Sim, Frederick Piper, the Second World War the Mona Lisa Harry Fowler. A gang of street boys is moved to a London gallery, where a foil a crook who sends commands for German art collector tries to steal it. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Winter Series Art Films and Events January February Filmmarch Film

Film Program Winter 2008 National Gallery of Art, Washington Winter Series film From the Archives: 16 at 12 England’s New Wave, 1958 – 1964 István Szabó’s 20th Century Alexander Sokurov In Glorious Technicolor Art Films and Events This Sporting Life (Photofest) 19 Sat II March Edward 2:00 England’s New Wave, 1958 – 1964: A Kind of Loving 1 Sat J. M.W. Turner and Film 4:30 England’s New Wave, 1958 – 1964: 2:00 István Szabó’s 20th Century: Mephisto (two-part program) This Sporting Life 4:30 István Szabó’s 20th Century: Colonel Redl 2 Sun The Gates 20 Sun 4:30 England’s New Wave, 1958 – 1964: 4:30 István Szabó’s 20th Century: Hanussen International Festival of Films Saturday Night and Sunday Morning; 4 Tues The Angry Silence on Art 12:00 From the Archives: 16 at 12: The City 22 Tues of Washington Henri Storck’s Legacy: 12:00 From the Archives: 16 at 12: Dorothea 8 Sat Lange: Under the Trees; Eugène Atget (1856 – 1927) Belgian Films on Art 3:00 Event: Max Linder Ciné-Concert 26 Sat 9 Sun 2:00 Event: International Festival of Films on Art England’s Finest Hour: 4:30 Alexander Sokurov: The Sun (Solntse) Films by Humphrey Jennings 27 Sun 11 Tues 4:00 Event: International Festival of Films on Art Balázs Béla Stúdió: 1961 – 1970 12:00 From the Archives: 16 at 12: Washington, 29 Tues City with a Plan Max Linder Ciné-Concert 12:00 From the Archives: 16 at 12: Dorothea 15 Sat Lange: Under the Trees; Eugène Atget (1856 – 1927) 2:30 Alexander Sokurov: Elegy of Life: Silvestre Revueltas: Music for Film Rostropovich Vishnevskaya February 4:30 Alexander -

Liminal Soundscapes in Powell & Pressburger's Wartime Films

Liminal soundscapes in Powell & Pressburger’s wartime films Anita Jorge To cite this version: Anita Jorge. Liminal soundscapes in Powell & Pressburger’s wartime films. Studies in European Cinema, Intellect, 2016, 14 (1), pp.22 - 32. 10.1080/17411548.2016.1248531. hal-01699401 HAL Id: hal-01699401 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01699401 Submitted on 8 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Liminal soundscapes in Powell & Pressburger’s wartime films Anita Jorge Université de Lorraine This article explores Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s wartime films through the prism of the soundscape, focusing on the liminal function of sound. Dwelling on such films as 49th Parallel (1941) and One of Our Aircraft is Missing (1942), it argues that sound acts as a diegetic tool translating the action into a spatiotemporal elsewhere, as well as a liberation tool, enabling the people threatened by Nazi assimilation to reach for a more permissive world where restrictions no longer operate. Lastly, the soundscape serves as a ‘translanguage’, bridging the gap between soldiers and civilians, or between different nations fighting against a common enemy, thus giving birth to a transnational community. -

415 REVIEWS Area, Produced by the Romney Marsh Research Trust (RMRT) and Its Antecedents

Archaeologia Cantiana - Vol. 131 2011 REVIEWS Excavations at Market Way St Stephen’s, Canterbury. By Richard Helm and Jon Rady. ix + 90 pp. 35 figs, 30 plates and 33 tables. CAT Occasional Paper No. 8, 2011. Paperback, £13.95. ISBN 978-1-870545-2-1. This very recently published report on the Market Way excavations adds considerably to the knowledge and understanding of the importance of suburban sites peripheral to Canterbury. Activity on this site has been dated to the Mesolithic, through the Neolithic to the transition of the Bronze to the Iron Age. After an apparent break in use of the site there is evidence of late Iron Age and early Roman agricultural activity along the Stour reflecting a trend already identified in the area. Although the excavations did not uncover as much as was hoped to consolidate the nearby findings by Frank Jenkins in the 1950s, sufficient evidence remained of the suburban pottery and tile industry which emerged in Canterbury suburbs during the first and second centuries AD, fixing the Market Way site into the overall pattern of activity along the Stour. From the mid-second century AD signs of abandonment are all that remain. The possible existence of a Roman road running from Northgate to the Market Way site is sustained by later Roman inhumation burials along the route, and the use of the route after a four hundred year hiatus, when the next agricultural settlements, evidenced by field patterns, emerged in the eighth century, only to be abandoned after the middle of the ninth century. Thereafter the site remained unoccupied until late post-medieval horticultural usage.