The Health and Environmental Impacts of Hazardous Wastes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transport of Dangerous Goods

ST/SG/AC.10/1/Rev.16 (Vol.I) Recommendations on the TRANSPORT OF DANGEROUS GOODS Model Regulations Volume I Sixteenth revised edition UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2009 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ST/SG/AC.10/1/Rev.16 (Vol.I) Copyright © United Nations, 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may, for sales purposes, be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the United Nations. UNITED NATIONS Sales No. E.09.VIII.2 ISBN 978-92-1-139136-7 (complete set of two volumes) ISSN 1014-5753 Volumes I and II not to be sold separately FOREWORD The Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods are addressed to governments and to the international organizations concerned with safety in the transport of dangerous goods. The first version, prepared by the United Nations Economic and Social Council's Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods, was published in 1956 (ST/ECA/43-E/CN.2/170). In response to developments in technology and the changing needs of users, they have been regularly amended and updated at succeeding sessions of the Committee of Experts pursuant to Resolution 645 G (XXIII) of 26 April 1957 of the Economic and Social Council and subsequent resolutions. -

Assessment of Portable HAZMAT Sensors for First Responders

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Assessment of Portable HAZMAT Sensors for First Responders Author(s): Chad Huffman, Ph.D., Lars Ericson, Ph.D. Document No.: 246708 Date Received: May 2014 Award Number: 2010-IJ-CX-K024 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant report available electronically. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Assessment of Portable HAZMAT Sensors for First Responders DOJ Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice Sensor, Surveillance, and Biometric Technologies (SSBT) Center of Excellence (CoE) March 1, 2012 Submitted by ManTech Advanced Systems International 1000 Technology Drive, Suite 3310 Fairmont, West Virginia 26554 Telephone: (304) 368-4120 Fax: (304) 366-8096 Dr. Chad Huffman, Senior Scientist Dr. Lars Ericson, Director UNCLASSIFIED This project was supported by Award No. 2010-IJ-CX-K024, awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Urine Elements Resource Guide

Urine Elements Resource Guide Science + Insight doctorsdata.com Doctor’s Data, Inc. Urine Elements Resource Guide B Table of Contents Sample Report Sample Report ........................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Urine Toxic Metals Profile Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................................3 Aluminum .....................................................................................................................................................................................3 Antimony .......................................................................................................................................................................................4 Arsenic ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Barium ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Beryllium ........................................................................................................................................................................................5 Bismuth ......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

1/2 Toxic Compound Data Sheet Name: Indene CAS Number: 00095

1/2 Toxic Compound Data Sheet Name: Indene CAS Number: 00095-13-6 Justification: This compound is listed in Ohio Administrative Code 3745 - 114 - 01 because it fulfills one or more of the following criteria: substances that are known to be, or may reasonably be anticipated to be, carcinogenic, mutagenic, teratogenic, or neurotoxic, causes reproductive dysfunction, is acutely or chronically toxic, or causes the threat of adverse environmental effects through ambient concentrations, bioaccumulation, or atmospheric deposition. lndene is acutely toxic with effects on the upper respiratory system (mucous membranes), pulmonary irritation, liver and kidney effects. Molecular Weight (g/mol): 116.15 Synonyms: Indonaphthene U.S. EPA Carcinogenic Classification (IRIS): Not listed on IRIS. PBT: Not listed as persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic. NTP: Not listed by the National Toxicology Program. HAP: Not listed as a hazardous air pollutant (HAP) by U.S. EPA. 112r: Not listed under Section 112(r) of the Clean Air Act. ACGIH: TLV: 10 ppm or 47,505 µg/m3. Critical effects include upper respiratory irritation or damage, pulmonary irritation, and liver and kidney effects. HSDB: Listed in the Hazardous Substances Data Bank. Inhalation of indene vapors is expected to cause irritation of mucous membranes. International IARC: Not listed by International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). ATSDR (MRL): Not listed by ATSDR. DataSheet Indene.wpd 2/2 Reference Material 1. American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) 2006. TLVs and BEIs: -

Selenium Hexafluoride INTERIM 1: 11-2007 1 2 3 INTERIM ACUTE EXPOSURE GUIDELINE LEVELS (Aegls) 5 for 6 Selenium Hexafluoride 7 (CAS Reg

Selenium Hexafluoride INTERIM 1: 11-2007 1 2 3 INTERIM ACUTE EXPOSURE GUIDELINE LEVELS (AEGLs) 5 FOR 6 Selenium Hexafluoride 7 (CAS Reg. No. 7783-79-1) 8 9 Se-F6 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Selenium Hexafluoride INTERIM 1: 11-2007 1 INTERIM ACUTE EXPOSURE GUIDELINE LEVELS (AEGLs) 3 FOR 4 SELENIUM HEXAFLUORIDE 5 (CAS Reg. No. 7783-79-1) 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 4 Selenium Hexafluoride INTERIM 1: 11-2007 1 2 3 4 5 PREFACE 6 7 Under the authority of the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) P. L. 92-463 of 8 1972, the National Advisory Committee for Acute Exposure Guideline Levels for Hazardous 9 Substances (NAC/AEGL Committee) has been established to identify, review and interpret 10 relevant toxicologic and other scientific data and develop AEGLs for high priority, acutely toxic 11 chemicals. 12 13 AEGLs represent threshold exposure limits for the general public and are applicable to 14 emergency exposure periods ranging from 10 minutes to 8 hours. Three levels C AEGL-1, 15 AEGL-2 and AEGL-3 C are developed for each of five exposure periods (10 and 30 minutes, 1 16 hour, 4 hours, and 8 hours) and are distinguished by varying degrees of severity of toxic effects. 17 The three AEGLs are defined as follows: 18 19 AEGL-1 is the airborne concentration (expressed as parts per million or milligrams per 20 cubic meter [ppm or mg/m3]) of a substance above which it is predicted that the general 21 population, including susceptible individuals, could experience notable discomfort, irritation, or 22 certain asymptomatic, non-sensory effects. -

View PDF Version

Nanoscale View Article Online REVIEW View Journal | View Issue Synthesis of emerging 2D layered magnetic materials Cite this: Nanoscale, 2021, 13, 2157 Mauro Och,a Marie-Blandine Martin,b Bruno Dlubak, b Pierre Seneorb and Cecilia Mattevi *a van der Waals atomically thin magnetic materials have been recently discovered. They have attracted enormous attention as they present unique magnetic properties, holding potential to tailor spin-based device properties and enable next generation data storage and communication devices. To fully under- stand the magnetism in two-dimensions, the synthesis of 2D materials over large areas with precise thick- ness control has to be accomplished. Here, we review the recent advancements in the synthesis of these materials spanning from metal halides, transition metal dichalcogenides, metal phosphosulphides, to ternary metal tellurides. We initially discuss the emerging device concepts based on magnetic van der Waals materials including what has been achieved with graphene. We then review the state of the art of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence. the synthesis of these materials and we discuss the potential routes to achieve the synthesis of wafer- scale atomically thin magnetic materials. We discuss the synthetic achievements in relation to the struc- Received 3rd November 2020, tural characteristics of the materials and we scrutinise the physical properties of the precursors in relation Accepted 8th January 2021 to the synthesis conditions. We highlight the challenges related to the synthesis of 2D magnets and we DOI: 10.1039/d0nr07867k provide a perspective for possible advancement of available synthesis methods to respond to the need for rsc.li/nanoscale scalable production and high materials quality. -

Cal/OSHA, DOT HAZMAT, EEOC, EPA, HIPAA, IATA, IMDG, TDG, MSHA, OSHA, Australia WHS, and Canada OHS Regulations and Safety Online Training

! Cal/OSHA, DOT HAZMAT, EEOC, EPA, HIPAA, IATA, IMDG, TDG, MSHA, OSHA, Australia WHS, and Canada OHS Regulations and Safety Online Training This document is provided as a training aid and may not reflect current laws and regulations. Be sure and consult with the appropriate governing agencies or publication providers listed in the "Resources" section of our website. www.ComplianceTrainingOnline.com ! ! ! ! ! Facebook LinkedIn Twitter Google Plus Website Hazardous Chemicals Handbook Second edition Phillip Carson PhD MSc AMCT CChem FRSC FIOSH Head of Science Support Services, Unilever Research Laboratory, Port Sunlight, UK Clive Mumford BSc PhD DSc CEng MIChemE Consultant Chemical Engineer Oxford Amsterdam Boston London New York Paris San Diego San Francisco Singapore Sydney Tokyo Butterworth-Heinemann An imprint of Elsevier Science Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 225 Wildwood Avenue, Woburn, MA 01801-2041 First published 1994 Second edition 2002 Copyright © 1994, 2002, Phillip Carson, Clive Mumford. All rights reserved The right of Phillip Carson and Clive Mumford to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1T 4LP. -

Chemical Names and CAS Numbers Final

Chemical Abstract Chemical Formula Chemical Name Service (CAS) Number C3H8O 1‐propanol C4H7BrO2 2‐bromobutyric acid 80‐58‐0 GeH3COOH 2‐germaacetic acid C4H10 2‐methylpropane 75‐28‐5 C3H8O 2‐propanol 67‐63‐0 C6H10O3 4‐acetylbutyric acid 448671 C4H7BrO2 4‐bromobutyric acid 2623‐87‐2 CH3CHO acetaldehyde CH3CONH2 acetamide C8H9NO2 acetaminophen 103‐90‐2 − C2H3O2 acetate ion − CH3COO acetate ion C2H4O2 acetic acid 64‐19‐7 CH3COOH acetic acid (CH3)2CO acetone CH3COCl acetyl chloride C2H2 acetylene 74‐86‐2 HCCH acetylene C9H8O4 acetylsalicylic acid 50‐78‐2 H2C(CH)CN acrylonitrile C3H7NO2 Ala C3H7NO2 alanine 56‐41‐7 NaAlSi3O3 albite AlSb aluminium antimonide 25152‐52‐7 AlAs aluminium arsenide 22831‐42‐1 AlBO2 aluminium borate 61279‐70‐7 AlBO aluminium boron oxide 12041‐48‐4 AlBr3 aluminium bromide 7727‐15‐3 AlBr3•6H2O aluminium bromide hexahydrate 2149397 AlCl4Cs aluminium caesium tetrachloride 17992‐03‐9 AlCl3 aluminium chloride (anhydrous) 7446‐70‐0 AlCl3•6H2O aluminium chloride hexahydrate 7784‐13‐6 AlClO aluminium chloride oxide 13596‐11‐7 AlB2 aluminium diboride 12041‐50‐8 AlF2 aluminium difluoride 13569‐23‐8 AlF2O aluminium difluoride oxide 38344‐66‐0 AlB12 aluminium dodecaboride 12041‐54‐2 Al2F6 aluminium fluoride 17949‐86‐9 AlF3 aluminium fluoride 7784‐18‐1 Al(CHO2)3 aluminium formate 7360‐53‐4 1 of 75 Chemical Abstract Chemical Formula Chemical Name Service (CAS) Number Al(OH)3 aluminium hydroxide 21645‐51‐2 Al2I6 aluminium iodide 18898‐35‐6 AlI3 aluminium iodide 7784‐23‐8 AlBr aluminium monobromide 22359‐97‐3 AlCl aluminium monochloride -

Bacterial Recovery and Recycling of Tellurium from Tellurium- Containing Compounds by Pseudoalteromonas Sp

Bacterial recovery and recycling of tellurium from tellurium- containing compounds by Pseudoalteromonas sp. EPR3 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bonificio, W.D., and D.R. Clarke. 2014. “ Bacterial Recovery and Recycling of Tellurium from Tellurium-Containing Compounds by Pseudoalteromonas Sp. EPR3 .” Journal of Applied Microbiology 117 (5) (September 26): 1293–1304. doi:10.1111/jam.12629. Published Version doi:10.1111/jam.12629 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:13572100 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP 1 For submission to Journal of Applied Microbiology 2 3 Bacterial recovery and recycling of tellurium from tellurium-containing 4 compounds by Pseudoalteromonas sp. EPR3 5 William D. Bonificio #, David R. Clarke 6 7 School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, 29 Oxford St., 8 Cambridge, MA 02138, United States 9 10 Running Title: Bacterial recovery of tellurium 11 12 # Corresponding Author to whom inquiries should be addressed. 13 Mailing address: McKay 405, 9 Oxford St. Cambridge, MA 02138. 14 Email address: [email protected] 15 16 Keywords: Pseudoalteromonas; tellurium; tellurite; recycling; tellurium-containing 17 compounds. 1 18 ABSTRACT 19 Aims: Tellurium based devices, such as photovoltaic (PV) modules and 20 thermoelectric generators, are expected to play an increasing role in renewable energy 21 technologies. -

Lists of Gases for Pcard Manual.Xlsx

GASES THAT ARE PROHIBITED FROM PURCHASE WITH A P-CARD (Please note, this list is not all-inclusive. It is maintained by the Office of Research Safety. The office can be contacted at 706-542-9088 with any questions or comments.) Gas CAS Number Hazards Ammonia 7664‐41‐7 Corrosive Highly toxic, Arsine 7784–42–1 flammable, pyrophoric Boron tribromide 10294–33–4 Toxic, corrosive Boron trichloride 10294–34–5 Corrosive Boron trifluoride 7637–07–2 Toxic, corrosive Highly toxic, Bromine 7726–95–6 corrosive Toxic, Carbon monoxide 630–08–0 flammable Toxic, corrosive, Chlorine 7782–50–5 oxidizer Chlorine dioxide 10049–04–4 Toxic, oxidizer Chlorine trifluoride 7790–91–2 Toxic, oxidizer, corrosive Highly toxic, Diborane 19278–45–7 flammable, Dichlorosilane 4109–96–0 Toxic, corrosive Ethylene oxide 75–21–8 Toxic, flammable Highly toxic, corrosive, Fluorine 7782–41–4 oxidizer Highly toxic, Germane 7782–65–2 flammable Hydrogen bromide 10035–10–6 Toxic, corrosive Hydrogen chloride 7647–01–0 Toxic, corrosive Hydrogen cyanide 74–90–8 Highly toxic, flammable Hydrogen fluoride 7664–39–3 Toxic, corrosive Hydrogen iodide 10034‐85‐2 Toxic, corrosive Highly toxic, Hydrogen selenide 7783–07–5 flammable Toxic, flammable, Hydrogen sulfide 7783–06–4 corrosive Methyl bromide 74–83–9 Toxic Methyl isocyanate 624‐83‐9 Highly toxic, flammable Methyl mercaptan 74–93–1 Toxic, flammable Nickel carbonyl 13463–39–3 Highly toxic, flammable Highly toxic, Nitric oxide 10102–43–9 oxidizer Highly toxic, Nitrogen dioxide 10102–44–0 oxidizer, corrosive Highly toxic, Ozone 10028‐15‐6 -

TIH/PIH List

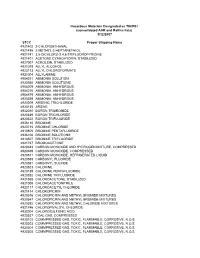

Hazardous Materials Designated as TIH/PIH (consolidated AAR and Railinc lists) 3/12/2007 STCC Proper Shipping Name 4921402 2-CHLOROETHANAL 4921495 2-METHYL-2-HEPTANETHIOL 4921741 3,5-DICHLORO-2,4,6-TRIFLUOROPYRIDINE 4921401 ACETONE CYANOHYDRIN, STABILIZED 4927007 ACROLEIN, STABILIZED 4921019 ALLYL ALCOHOL 4923113 ALLYL CHLOROFORMATE 4921004 ALLYLAMINE 4904211 AMMONIA SOLUTION 4920360 AMMONIA SOLUTIONS 4904209 AMMONIA, ANHYDROUS 4904210 AMMONIA, ANHYDROUS 4904879 AMMONIA, ANHYDROUS 4920359 AMMONIA, ANHYDROUS 4923209 ARSENIC TRICHLORIDE 4920135 ARSINE 4932010 BORON TRIBROMIDE 4920349 BORON TRICHLORIDE 4920522 BORON TRIFLUORIDE 4936110 BROMINE 4920715 BROMINE CHLORIDE 4918505 BROMINE PENTAFLUORIDE 4936106 BROMINE SOLUTIONS 4918507 BROMINE TRIFLUORIDE 4921727 BROMOACETONE 4920343 CARBON MONOXIDE AND HYDROGEN MIXTURE, COMPRESSED 4920399 CARBON MONOXIDE, COMPRESSED 4920511 CARBON MONOXIDE, REFRIGERATED LIQUID 4920559 CARBONYL FLUORIDE 4920351 CARBONYL SULFIDE 4920523 CHLORINE 4920189 CHLORINE PENTAFLUORIDE 4920352 CHLORINE TRIFLUORIDE 4921558 CHLOROACETONE, STABILIZED 4921009 CHLOROACETONITRILE 4923117 CHLOROACETYL CHLORIDE 4921414 CHLOROPICRIN 4920516 CHLOROPICRIN AND METHYL BROMIDE MIXTURES 4920547 CHLOROPICRIN AND METHYL BROMIDE MIXTURES 4920392 CHLOROPICRIN AND METHYL CHLORIDE MIXTURES 4921746 CHLOROPIVALOYL CHLORIDE 4930204 CHLOROSULFONIC ACID 4920527 COAL GAS, COMPRESSED 4920102 COMMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, FLAMMABLE, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920303 COMMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, FLAMMABLE, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920304 COMMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, FLAMMABLE, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920305 COMMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, FLAMMABLE, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920101 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920300 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920301 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920324 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920331 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920165 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, FLAMMABLE, N.O.S. 4920378 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, FLAMMABLE, N.O.S. 4920379 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, FLAMMABLE, N.O.S. -

1 Draft Chemicals (Management and Safety)

Draft Chemicals (Management and Safety) Rules, 20xx In exercise of the powers conferred by Sections 3, 6 and 25 of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 (29 of 1986), and in supersession of the Manufacture, Storage and Import of Hazardous Chemical Rules, 1989 and the Chemical Accidents (Emergency Planning. Preparedness and Response) Rules, 1996, except things done or omitted to be done before such supersession, the Central Government hereby makes the following Rules relating to the management and safety of chemicals, namely: 1. Short Title and Commencement (1) These Rules may be called the Chemicals (Management and Safety) Rules, 20xx. (2) These Rules shall come into force on the date of their publication in the Official Gazette. Chapter I Definitions, Objectives and Scope 2. Definitions (1) In these Rules, unless the context otherwise requires (a) “Act” means the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 (29 of 1986) as amended from time to time; (b) “Article” means any object whose function is determined by its shape, surface or design to a greater degree than its chemical composition; (c) “Authorised Representative” means a natural or juristic person in India who is authorised by a foreign Manufacturer under Rule 6(2); (d) “Chemical Accident” means an accident involving a sudden or unintended occurrence while handling any Hazardous Chemical, resulting in exposure (continuous, intermittent or repeated) to the Hazardous Chemical causing death or injury to any person or damage to any property, but does not include an accident by reason only