The Magellan Spacecraft at Venus by Andrew Fraknoi, Astronomical Society of the Pacific

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission to Jupiter

This book attempts to convey the creativity, Project A History of the Galileo Jupiter: To Mission The Galileo mission to Jupiter explored leadership, and vision that were necessary for the an exciting new frontier, had a major impact mission’s success. It is a book about dedicated people on planetary science, and provided invaluable and their scientific and engineering achievements. lessons for the design of spacecraft. This The Galileo mission faced many significant problems. mission amassed so many scientific firsts and Some of the most brilliant accomplishments and key discoveries that it can truly be called one of “work-arounds” of the Galileo staff occurred the most impressive feats of exploration of the precisely when these challenges arose. Throughout 20th century. In the words of John Casani, the the mission, engineers and scientists found ways to original project manager of the mission, “Galileo keep the spacecraft operational from a distance of was a way of demonstrating . just what U.S. nearly half a billion miles, enabling one of the most technology was capable of doing.” An engineer impressive voyages of scientific discovery. on the Galileo team expressed more personal * * * * * sentiments when she said, “I had never been a Michael Meltzer is an environmental part of something with such great scope . To scientist who has been writing about science know that the whole world was watching and and technology for nearly 30 years. His books hoping with us that this would work. We were and articles have investigated topics that include doing something for all mankind.” designing solar houses, preventing pollution in When Galileo lifted off from Kennedy electroplating shops, catching salmon with sonar and Space Center on 18 October 1989, it began an radar, and developing a sensor for examining Space interplanetary voyage that took it to Venus, to Michael Meltzer Michael Shuttle engines. -

Venus Aerobot Multisonde Mission

w AIAA Balloon Technology Conference 1999 Venus Aerobot Multisonde Mission By: James A. Cutts ('), Viktor Kerzhanovich o_ j. (Bob) Balaram o), Bruce Campbell (2), Robert Gershman o), Ronald Greeley o), Jeffery L. Hall ('), Jonathan Cameron o), Kenneth Klaasen v) and David M. Hansen o) ABSTRACT requires an orbital relay system that significantly Robotic exploration of Venus presents many increases the overall mission cost. The Venus challenges because of the thick atmosphere and Aerobot Multisonde (VAMuS) Mission concept the high surface temperatures. The Venus (Fig 1 (b) provides many of the scientific Aerobot Multisonde mission concept addresses capabilities of the VGA, with existing these challenges by using a robotic balloon or technology and without requiring an orbital aerobot to deploy a number of short lifetime relay. It uses autonomous floating stations probes or sondes to acquire images of the (aerobots) to deploy multiple dropsondes capable surface. A Venus aerobot is not only a good of operating for less than an hour in the hot lower platform for precision deployment of sondes but atmosphere of Venus. The dropsondes, hereafter is very effective at recovering high rate data. This described simply as sondes, acquire high paper describes the Venus Aerobot Multisonde resolution observations of the Venus surface concept and discusses a proposal to NASA's including imaging from a sufficiently close range Discovery program using the concept for a that atmospheric obscuration is not a major Venus Exploration of Volcanoes and concern and communicate these data to the Atmosphere (VEVA). The status of the balloon floating stations from where they are relayed to deployment and inflation, balloon envelope, Earth. -

Envision Conference

Image credit: JAXA/DART/Damia Bouic NASA/GSFC/U. Arizona http://envisionvenus.eu http:/bit.ly/venus2020 M5/EnVision Project Cosmic Vision mission timeline M3 M1 M2 M5 M4 Image credit: http://envisionvenus.eu ESA Science - adapted from Wikipedia M5/EnVision : timeline Apr. 2016: Release of call for M5 mission Oct. 2016: EnVision proposal submitted Jan. 2017: 1st programmatic evaluation rejected Feb. 2017: EnVision scientific & programmatic evaluation resumes May 2018: ESA selects 3 M5 mission concepts to study Jun. 2018: ESA Science Directorate forms Science Study Team (SST) Nov 2018: CDF study (Phase 0) completed / EnVision Mission Definition Review (MDR) 2019-2020: Industrial phase A study (2 independent ESA contractors) Image credit M5/EnVision Project Mar. 2020 : EnVision Mission Consolidation Review (MCR) Dec. 2020 : EnVision Assessment Study Report (Yellow Book) Feb. 2021 : EnVision Mission Selection Review (MSR) http://envisionvenus.eu Image credit ESA Three very different M5 finalists "A high-energy survey of the early Universe, an infrared observatory to study the formation of stars, planets and galaxies, and a Venus orbiter are to be considered for ESA’s fifth medium class mission in its Cosmic Vision science programme, with a planned launch date in 2032." Spectroscopy from 12 to 230 μ Soft X-ray, X-gamma rays LEO orbit Image credit M5/EnVision Project M5/SPICA Project http://envisionvenus.eu M5/Theseus Project DAY 1 You are warmly invited to join •EnVision mission overview the international conference •Surface to discuss the scientific Magellan heritage investigations of ESA's DAY 2 EnVision mission. •Interior structure (radial : tidal, viscosity, crust, lithosphere structure) The conference will welcome •Activity detection all presentations related to DAY 3 the mission’s payload an its •Atmosphere VEx, Akatsuki Heritage science investigations. -

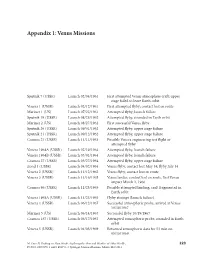

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

GRAIL Twins Toast New Year from Lunar Orbit

Jet JANUARY Propulsion 2012 Laboratory VOLUME 42 NUMBER 1 GRAIL twins toast new year from Three-month ‘formation flying’ mission will By Mark Whalen lunar orbit study the moon from crust to core Above: The GRAIL team celebrates with cake and apple cider. Right: Celebrating said. “So it does take a lot of planning, a lot of test- the other spacecraft will accelerate towards that moun- GRAIL-A’s Jan. 1 lunar orbit insertion are, from left, Maria Zuber, GRAIL principal ing and then a lot of small maneuvers in order to get tain to measure it. The change in the distance between investigator, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Charles Elachi, JPL director; ready to set up to get into this big maneuver when we the two is noted, from which gravity can be inferred. Jim Green, NASA director of planetary science. go into orbit around the moon.” One of the things that make GRAIL unique, Hoffman JPL’s Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) A series of engine burns is planned to circularize said, is that it’s the first formation flying of two spacecraft mission celebrated the new year with successful main the twins’ orbit, reducing their orbital period to a little around any body other than Earth. “That’s one of the engine burns to place its twin spacecraft in a perfectly more than two hours before beginning the mission’s biggest challenges we have, and it’s what makes this an synchronized orbit around the moon. 82-day science phase. “If these all go as planned, we exciting mission,” he said. -

From Hayabusa to Hayabusa2: Present Status and Plans for Sample Curations of Asteroidal Sample Return Missions by Jaxa

81st Annual Meeting of The Meteoritical Society 2018 (LPI Contrib. No. 2067) 6117.pdf FROM HAYABUSA TO HAYABUSA2: PRESENT STATUS AND PLANS FOR SAMPLE CURATIONS OF ASTEROIDAL SAMPLE RETURN MISSIONS BY JAXA. T. Yada1, K. Sakamoto1, M. Yoshitake1, K. Kumagai2, M. Nishimura2, Y. Nakano1, S. Furuya1, M. Abe1, T. Okada1, S. Tachibana3, H. Yurimoto1,4, and M. Fujimoto1,5, 1Astromat. Sci. Res. Group, Inst. Space Astronaut. Sci., Japan Aerosp. Explor. Agnecy, 3-1-1 Yoshinodai, Chuo, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 252-5210, Japan ([email protected]), 2 Marine Works Japan Ltd., 3-54-1 Oppamahigashi, Yokosuka 237-0063 Japan, 3Dept. Earth Planet. Sci., Grad. Sch. Science, Univ. Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan, 4Dept. Earth Science, Grad. Sch. Science, Hokkaido Univ., Kita 8, Nishi 5, Kita, Sapporo, Hokkaido 060-0808, Japan, 5Earth-Life Sci. Inst., Tokyo Inst. Tech., 2-12-1-1E-1 Ookayama, Meguro, Tokyo 152-8550, Japan. Introduction: The new era of sample return missions had started since the Stardust returned samples from com- et 81P/Wild 2 in 2006 [1], followed by the Hayabusa spacecraft from the near-Earth S-type asteroid 25143 Itokawa in 2010 [2,3]. In this year, Hayabusa2 will reach its target body, the near-Earth C-type asteroid 162173 Ryugu [4], and also OSIRIS-REx toward the near-Earth B-type asteroid 101955 Bennu [5]. Additionally, several other sample return missions have been planned recently, such as the Martian Moons eXplorer (MMX) for the Phobos and/or Deimos [6], the CAESAR for 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko [7], and the HELACLES for the the Moon [8]. -

Climate Histories of Mars and Venus, and the Habitability of Planets

CLIMATE HISTORIES OF MARS AND VENUS, AND THE HABITABILITY OF PLANETS In the temporal sequence that Part III of the book has ¡NTRODUCT¡ON 15.1 been following, we stand near the end of the Archean eon. Earth at the close of the Archean,2.5 billion years ago, By this point in time, the evolution of Venus and its atmo- was a world in which life had arisen and plate tectonics sphere almost certainly had diverged from that of Earth, dominated, the evolution of the crust and the recycling of and Mars was on its way to being a cold, dry world, if volatiles. Yet oxygen (Oz) still was not prevalent in the it had not already become one. This is the appropriate atmosphere, which was richer in COz than at present. In moment in geologic time, then, to consider how Earth's this last respect, Earth's atmosphere was somewhat like neighboring planets diverged so greatly in climate, and to that of its neighbors, Mars and Venus, which today retain ponder the implications for habitable planets throughout this more primitive kind of atmosphere. the cosmos. In the following chapter, we consider why Speculations on the nature of Mars and Venus were, Earth became dominated by plate tectonics, but Venus prior to the space program, heavily influenced by Earth- and Mars did not. Understanding this is part of the key centered biases and the poor quality of telescopic observa- to understanding Earth's clement climate as discussed in tions (figure 15.1). Thirty years of U.S. and Soviet robotic chapter 1.4. -

Cassini RADAR Sequence Planning and Instrument Performance Richard D

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON GEOSCIENCE AND REMOTE SENSING, VOL. 47, NO. 6, JUNE 2009 1777 Cassini RADAR Sequence Planning and Instrument Performance Richard D. West, Yanhua Anderson, Rudy Boehmer, Leonardo Borgarelli, Philip Callahan, Charles Elachi, Yonggyu Gim, Gary Hamilton, Scott Hensley, Michael A. Janssen, William T. K. Johnson, Kathleen Kelleher, Ralph Lorenz, Steve Ostro, Member, IEEE, Ladislav Roth, Scott Shaffer, Bryan Stiles, Steve Wall, Lauren C. Wye, and Howard A. Zebker, Fellow, IEEE Abstract—The Cassini RADAR is a multimode instrument used the European Space Agency, and the Italian Space Agency to map the surface of Titan, the atmosphere of Saturn, the Saturn (ASI). Scientists and engineers from 17 different countries ring system, and to explore the properties of the icy satellites. have worked on the Cassini spacecraft and the Huygens probe. Four different active mode bandwidths and a passive radiometer The spacecraft was launched on October 15, 1997, and then mode provide a wide range of flexibility in taking measurements. The scatterometer mode is used for real aperture imaging of embarked on a seven-year cruise out to Saturn with flybys of Titan, high-altitude (around 20 000 km) synthetic aperture imag- Venus, the Earth, and Jupiter. The spacecraft entered Saturn ing of Titan and Iapetus, and long range (up to 700 000 km) orbit on July 1, 2004 with a successful orbit insertion burn. detection of disk integrated albedos for satellites in the Saturn This marked the start of an intensive four-year primary mis- system. Two SAR modes are used for high- and medium-resolution sion full of remote sensing observations by a dozen instru- (300–1000 m) imaging of Titan’s surface during close flybys. -

The Magellan Spacecraft at Venus by Andrew Fraknoi, Astronomical Society of the Pacific

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 18 - Fall 1991 © 1991, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. The Magellan Spacecraft at Venus by Andrew Fraknoi, Astronomical Society of the Pacific "Having finally penetrated below the clouds of Venus, we find its surface to be naked [not hidden], revealing the history of hundreds of millions of years of geological activity. Venus is a geologist's dream planet.'' —Astronomer David Morrison This fall, the brightest star-like object you can see in the eastern skies before dawn isn't a star at all — it's Venus, the second closest planet to the Sun. Because Venus is so similar in diameter and mass to our world, and also has a gaseous atmosphere, it has been called the Earth's "sister planet''. Many years ago, scientists expected its surface, which is perpetually hidden beneath a thick cloud layer, to look like Earth's as well. Earlier this century, some people even imagined that Venus was a hot, humid, swampy world populated by prehistoric creatures! But we now know Venus is very, very different. New radar images of Venus, just returned from NASA's Magellan spacecraft orbiting the planet, have provided astronomers the clearest view ever of its surface, revealing unique geological features, meteor impact craters, and evidence of volcanic eruptions different from any others found in the solar system. This issue of The Universe in the Classroom is devoted to what Magellan is teaching us today about our nearest neighbor, Venus. Where is Venus, and what is it like? Spacecraft exploration of Venus's surface Magellan — a "recycled'' spacecraft How does Magellan take pictures through the clouds? What has Magellan revealed about Venus? How does Venus' surface compare with Earth's? What is the next step in Magellan's mission? If Venus is such an uninviting place, why are we interested in it? Reading List Why is it so hot on Venus? Where is Venus, and what is it like? Venus orbits the Sun in a nearly circular path between Mercury and the Earth, about 3/4 as far from our star as the Earth is. -

Magellan Health, Inc. 4800 N

29MAR201601032835 MAGELLAN HEALTH, INC. 4800 N. Scottsdale Road, Suite 4400 Scottsdale, Arizona 85251 MagellanHealth.com April 9, 2018 Dear Shareholder: You are cordially invited to attend the 2018 annual meeting of shareholders of Magellan Health, Inc., to be held on Thursday, May 24, 2018 at 7:30 a.m., local time, at Magellan Offices, G-2 Auditorium Level, 4800 N. Scottsdale Road, Scottsdale, Arizona 85251. This year, three (3) directors are nominated for election to our board of directors. At the meeting, shareholders will be asked to: (i) elect three (3) directors to serve until our 2019 annual meeting; (ii) approve, in an advisory vote, the compensation of our named executive officers; (iii) approve an amendment to our 2014 Employee Stock Purchase Plan to increase by 300,000 the number of shares available for issuance under the plan; (iv) ratify the appointment of Ernst & Young LLP as our independent auditor for fiscal year 2018; and (v) transact such other business as may properly come before the meeting or any adjournment or postponement thereof. The accompanying proxy statement provides a detailed description of these proposals. We urge you to read the accompanying materials so that you may be informed about the business to be addressed at the annual meeting. It is important that your shares be represented at the annual meeting. Accordingly, we ask you, whether or not you plan to attend the annual meeting, to complete, sign and date a proxy and submit it to us promptly or to otherwise vote in accordance with the instructions on your proxy card or other notice. -

Determination of Venus' Interior Structure with Envision

remote sensing Technical Note Determination of Venus’ Interior Structure with EnVision Pascal Rosenblatt 1,*, Caroline Dumoulin 1 , Jean-Charles Marty 2 and Antonio Genova 3 1 Laboratoire de Planétologie et Géodynamique, UMR-CNRS6112, Université de Nantes, 44300 Nantes, France; [email protected] 2 CNES, Space Geodesy Office, 31401 Toulouse, France; [email protected] 3 Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Sapienza University of Rome, 00184 Rome, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The Venusian geological features are poorly gravity-resolved, and the state of the core is not well constrained, preventing an understanding of Venus’ cooling history. The EnVision candidate mission to the ESA’s Cosmic Vision Programme consists of a low-altitude orbiter to investigate geological and atmospheric processes. The gravity experiment aboard this mission aims to determine Venus’ geophysical parameters to fully characterize its internal structure. By analyzing the radio- tracking data that will be acquired through daily operations over six Venusian days (four Earth’s years), we will derive a highly accurate gravity field (spatial resolution better than ~170 km), allowing detection of lateral variations of the lithosphere and crust properties beneath most of the geological ◦ features. The expected 0.3% error on the Love number k2, 0.1 error on the tidal phase lag and 1.4% error on the moment of inertia are fundamental to constrain the core size and state as well as the mantle viscosity. Keywords: planetary interior structure; gravity field determination; deep space mission Citation: Rosenblatt, P.; Dumoulin, C.; Marty, J.-C.; Genova, A. -

Extraterrestrial Geology Issue

Lite EXTRAT E RR E STRIAL GE OLO G Y ISSU E SPRING 2010 ISSUE 27 The Solar System. This illustration shows the eight planets and three of the five named dwarf planets in order of increasing distance from the Sun, although the distances between them are not to scale. The sizes of the bodies are shown relative to each other, and the colors are approximately natural. Image modified from NASA/JPL. IN TH I S ISSUE ... Extraterrestrial Geology Classroom Activity: Impact Craters • Celestial Crossword Puzzle Is There Life Beyond Earth? Meteorites in Antarctica Why Can’t I See the Milky Way? Most Wanted Mineral: Jarosite • Through the Hand Lens New Mexico’s Enchanting Geology • Short Items of Interest NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF GEOLOGY & MINERAL RESOURCES A DIVISION OF NEW MEXICO TECH EXTRAT E RR E STRIAL GE OLO G Y Douglas Bland The surface of the planet we live on was created by geologic Many factors affect the appearance, characteristics, and processes, resulting in mountains, valleys, plains, volcanoes, geology of a body in space. Size, composition, temperature, an ocean basins, and every other landform around us. Geology atmosphere (or lack of it), and proximity to other bodies are affects the climate, concentrates energy and mineral resources just a few. Through images and data gathered by telescopes, in Earth’s crust, and impacts the beautiful landscapes outside satellites orbiting Earth, and spacecraft sent into deep space, the window. The surface of Earth is constantly changing due it has become obvious that the other planets and their moons to the relentless effects of plate tectonics that move continents look very different from Earth, and there is a tremendous and create and destroy oceans.