Norovirus in Healthcare Facilities Fact Sheet Released December 21, 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antiviral Bioactive Compounds of Mushrooms and Their Antiviral Mechanisms: a Review

viruses Review Antiviral Bioactive Compounds of Mushrooms and Their Antiviral Mechanisms: A Review Dong Joo Seo 1 and Changsun Choi 2,* 1 Department of Food Science and Nutrition, College of Health and Welfare and Education, Gwangju University 277 Hyodeok-ro, Nam-gu, Gwangju 61743, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Food and Nutrition, School of Food Science and Technology, College of Biotechnology and Natural Resources, Chung-Ang University, 4726 Seodongdaero, Daeduck-myun, Anseong-si, Gyeonggi-do 17546, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-31-670-4589; Fax: +82-31-676-8741 Abstract: Mushrooms are used in their natural form as a food supplement and food additive. In addition, several bioactive compounds beneficial for human health have been derived from mushrooms. Among them, polysaccharides, carbohydrate-binding protein, peptides, proteins, enzymes, polyphenols, triterpenes, triterpenoids, and several other compounds exert antiviral activity against DNA and RNA viruses. Their antiviral targets were mostly virus entry, viral genome replication, viral proteins, and cellular proteins and influenced immune modulation, which was evaluated through pre-, simultaneous-, co-, and post-treatment in vitro and in vivo studies. In particular, they treated and relieved the viral diseases caused by herpes simplex virus, influenza virus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Some mushroom compounds that act against HIV, influenza A virus, and hepatitis C virus showed antiviral effects comparable to those of antiviral drugs. Therefore, bioactive compounds from mushrooms could be candidates for treating viral infections. Citation: Seo, D.J.; Choi, C. Antiviral Bioactive Compounds of Mushrooms Keywords: mushroom; bioactive compound; virus; infection; antiviral mechanism and Their Antiviral Mechanisms: A Review. -

Norovirus Infectious Agent Information Sheet

Norovirus Infectious Agent Information Sheet Introduction Noroviruses are non-enveloped (naked) RNA viruses with icosahedral nucleocapsid symmetry. The norovirus genome consists of (+) ssRNA, containing three open reading frames that encode for proteins required for transcription, replication, and assembly. There are five norovirus genogroups (GI-GV), and only GI, GII, and GIV infect humans. Norovirus belongs to the Caliciviridae family of viruses, and has had past names including, Norwalk virus and “winter-vomiting” disease. Epidemiology and Clinical Significance Noroviruses are considered the most common cause of outbreaks of non-bacterial gastroenteritis worldwide, are the leading cause of foodborne illness in the United States (58%), and account for 26% of hospitalizations and 10% of deaths associated with food consumption. Salad ingredients, fruit, and oysters are the most implicated in norovirus outbreaks. Aside from food and water, Noroviruses can also be transmitted by person to person contact and contact with environmental surfaces. The rapid spread of secondary infections occurs in areas where a large population is enclosed within a static environment, such as cruise ships, military bases, and institutions. Symptoms typically last for 24 to 48 hours, but can persist up to 96 hours in the immunocompromised. Pathogenesis, Immunity, Treatment and Prevention Norovirus is highly infectious due to low infecting dose, high excretion level (105 to 107 copies/mg stool), and continual shedding after clinical recovery (>1 month). The norovirus genome undergoes frequent change due to mutation and recombination, which increases its prevalence. Studies suggest that acquired immunity only last 6 months after infection. Gastroenteritis, an inflammation of the stomach and small and large intestines, is caused by norovirus infection. -

Viruses in Transplantation - Not Always Enemies

Viruses in transplantation - not always enemies Virome and transplantation ECCMID 2018 - Madrid Prof. Laurent Kaiser Head Division of Infectious Diseases Laboratory of Virology Geneva Center for Emerging Viral Diseases University Hospital of Geneva ESCMID eLibrary © by author Conflict of interest None ESCMID eLibrary © by author The human virome: definition? Repertoire of viruses found on the surface of/inside any body fluid/tissue • Eukaryotic DNA and RNA viruses • Prokaryotic DNA and RNA viruses (phages) 25 • The “main” viral community (up to 10 bacteriophages in humans) Haynes M. 2011, Metagenomic of the human body • Endogenous viral elements integrated into host chromosomes (8% of the human genome) • NGS is shaping the definition Rascovan N et al. Annu Rev Microbiol 2016;70:125-41 Popgeorgiev N et al. Intervirology 2013;56:395-412 Norman JM et al. Cell 2015;160:447-60 ESCMID eLibraryFoxman EF et al. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011;9:254-64 © by author Viruses routinely known to cause diseases (non exhaustive) Upper resp./oropharyngeal HSV 1 Influenza CNS Mumps virus Rhinovirus JC virus RSV Eye Herpes viruses Parainfluenza HSV Measles Coronavirus Adenovirus LCM virus Cytomegalovirus Flaviviruses Rabies HHV6 Poliovirus Heart Lower respiratory HTLV-1 Coxsackie B virus Rhinoviruses Parainfluenza virus HIV Coronaviruses Respiratory syncytial virus Parainfluenza virus Adenovirus Respiratory syncytial virus Coronaviruses Gastro-intestinal Influenza virus type A and B Human Bocavirus 1 Adenovirus Hepatitis virus type A, B, C, D, E Those that cause -

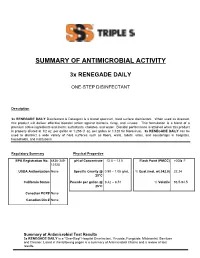

Summary of Antimicrobial Activity

SUMMARY OF ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY 3x RENEGADE DAILY ONE-STEP DISINFECTANT Description 3x RENEGADE DAILY Disinfectant & Detergent is a broad spectrum, hard surface disinfectant. When used as directed, this product will deliver effective biocidal action against bacteria, fungi, and viruses. This formulation is a blend of a premium active ingredients and inerts: surfactants, chelates, and water. Biocidal performance is attained when this product is properly diluted at 1/2 oz. per gallon or 1:256 (1 oz. per gallon or 1:128 for Norovirus). 3x RENEGADE DAILY can be used to disinfect a wide variety of hard surfaces such as floors, walls, toilets, sinks, and countertops in hospitals, households, and institutions. Regulatory Summary Physical Properties EPA Registration No. 6836-349- pH of Concentrate 12.0 – 13.5 Flash Point (PMCC) >200 F 12120 USDA Authorization None Specific Gravity @ 0.98 – 1.05 g/mL % Quat (mol. wt.342.0) 22.24 25°C California Status Pounds per gallon @ 8.42 – 8.51 % Volatile 93.5-94.5 25°C Canadian PCP# None Canadian Din # None Summary of Antimicrobial Test Results 3x RENEGADE DAILY is a "One-Step" Hospital Disinfectant, Virucide, Fungicide, Mildewstat, Sanitizer and Cleaner. Listed in the following pages is a summary of Antimicrobial Claims and a review of test results. Claim: Contact time: Organic Soil: Water Conditions: Disinfectant Varies 5% 250ppm as CaCO3 Test Method: AOAC Germicidal Spray Test Organism Contact Dilution Time (Min) 868 ppm (1/2oz. per Acinetobacter baumannii 3 Gal) Bordetella bronchiseptica 3 868 ppm Bordetella pertussis 3 868 ppm Campylobacter jejuni 3 868 ppm Enterobacter aerogenes 3 1736 PPM (1 oz per Gal) Enterococcus faecalis 3 868 ppm Enterococcus faecalis - Vancomycin resistant [VRE] 3 868 ppm Escherichia coli 3 868 ppm Escherichia coli [O157:H7] 3 868 ppm Escherichia coli ESBL – Extended spectrum beta- 868 ppm 10 lactamase containing E. -

Scwds Briefs

SCWDS BRIEFS A Quarterly Newsletter from the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study College of Veterinary Medicine The University of Georgia Phone (706) 542 - 1741 Athens, Georgia 30602 FAX (706) 542-5865 Volume 36 April 2020 Number 1 Working Together: The 40th Anniversary of limited HD reports probably relate to enzootic the National Hemorrhagic Disease Survey stability; on the northern edge, the low frequency of reports is likely driven by limited EHDV and BTV In the last issue of the SCWDS BRIEFS, hemorrhagic transmission due to either the absence of vectors or disease (HD) report data from Indiana, Ohio, environmental conditions that reduce vector numbers Kentucky, and West Virginia were highlighted to or their ability to transmit these viruses. Within these demonstrate how these long-term data can help states, east-west gradients in HD reporting also are detect and map the northern expansion of HD over evident. The factors that drive this within-state time. In addition to providing a means to detect variation are not well understood and possibly relate temporal changes in HD patterns, this long-term data to habitat gradients and complex set provides a window to better understand spatial vector/host/environmental interactions that are patterns and risks within areas where HD has unique to each individual state. historically occurred. In part two of this four-part series, we will explore HD patterns in another area – the Great Plains, where HD is commonly reported and large-scale outbreaks occasionally occur. These states were included in the survey in 1982, and thanks to their continued support, this data set now spans 38 years. -

Glycosphingolipids As Receptors for Non-Enveloped Viruses

Viruses 2010, 2, 1011-1049; doi:10.3390/v2041011 OPEN ACCESS viruses ISSN 1999-4915 www.mdpi.com/journal/viruses Review Glycosphingolipids as Receptors for Non-Enveloped Viruses Stefan Taube †, Mengxi Jiang † and Christiane E. Wobus * Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Michigan Medical School, 5622 Medical Sciences Bldg. II, 1150 West Medical Center Dr., Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (S.T.); [email protected] (M.J.) † These authors contributed equally to the work. * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-734-647-9599; Fax: +1-734-764-3562. Received: 2 March 2010; in revised form: 09 April 2010 / Accepted: 13 April 2010 / Published: 15 April 2010 Abstract: Glycosphingolipids are ubiquitous molecules composed of a lipid and a carbohydrate moiety. Their main functions are as antigen/toxin receptors, in cell adhesion/recognition processes, or initiation/modulation of signal transduction pathways. Microbes take advantage of the different carbohydrate structures displayed on a specific cell surface for attachment during infection. For some viruses, such as the polyomaviruses, binding to gangliosides determines the internalization pathway into cells. For others, the interaction between microbe and carbohydrate can be a critical determinant for host susceptibility. In this review, we summarize the role of glycosphingolipids as receptors for members of the non-enveloped calici-, rota-, polyoma- and parvovirus families. Keywords: non-enveloped virus; glycosphingolipid; receptor; calicivirus; rotavirus; polyomavirus; parvovirus 1. Introduction Viruses come in many different flavors and are often broadly classified based on their nucleic acid content (DNA versus RNA virus), capsid symmetry (icosahedral, helical, or complex), and the presence or absence of a lipid envelope (enveloped versus non-enveloped). -

Chapter 6 - Virology Viruses in Action!!

Chapter 6 - Virology Viruses in Action!! • Topics – Structure – Classification – Multiplication – Cultivation and replication – Nonviral infectious agent – Teratogenic/Oncogenic - Viruses have a host range. That is, viruses infect specific cells or tissues of specific hosts, or specific bacteria, Human or specific plants. Rhinovirus Common - Viral specificity refers to the specific Cold kinds of cells a virus can infect. It is regulated by the specificities of attachment, penetration and replication of the virus Properties of viruses A virion is an infectious virus particle - not all virus Viruses are not cells, do not have nuclei or particles are infectious mitochondria or ribosomes or other cellular Viruses are composed of a nucleic acid, RNA or DNA components. - never both . Viruses replicate or multiply. Viruses do not grow. All viruses have a protein coat or shell that surrounds Viruses replicate or multiply only within living cells. and protects the nucleic acid core. Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites . Some viruses have a lipid envelope or membrane surrounding a nucleocapsid core. The source of the The term virus was coined by Pasteur, and is from envelope is from the membranes of the host cell. the Latin word for poison. Some viruses package enzymes - e.g. RNA- Components of viruses - dependent-RNA polymerase or other enzymes - some do not package enzymes 1 Size comparison of viruses - how big are they? Structure • Size and morphology • Capsid • Envelope • Complex • Nucleic acid Mycoplasma? There are two major structures -

Structure Unveils Relationships Between RNA Virus Polymerases

viruses Article Structure Unveils Relationships between RNA Virus Polymerases Heli A. M. Mönttinen † , Janne J. Ravantti * and Minna M. Poranen * Molecular and Integrative Biosciences Research Programme, Faculty of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Helsinki, Viikki Biocenter 1, P.O. Box 56 (Viikinkaari 9), 00014 Helsinki, Finland; heli.monttinen@helsinki.fi * Correspondence: janne.ravantti@helsinki.fi (J.J.R.); minna.poranen@helsinki.fi (M.M.P.); Tel.: +358-2941-59110 (M.M.P.) † Present address: Institute of Biotechnology, Helsinki Institute of Life Sciences (HiLIFE), University of Helsinki, Viikki Biocenter 2, P.O. Box 56 (Viikinkaari 5), 00014 Helsinki, Finland. Abstract: RNA viruses are the fastest evolving known biological entities. Consequently, the sequence similarity between homologous viral proteins disappears quickly, limiting the usability of traditional sequence-based phylogenetic methods in the reconstruction of relationships and evolutionary history among RNA viruses. Protein structures, however, typically evolve more slowly than sequences, and structural similarity can still be evident, when no sequence similarity can be detected. Here, we used an automated structural comparison method, homologous structure finder, for comprehensive comparisons of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRps). We identified a common structural core of 231 residues for all the structurally characterized viral RdRps, covering segmented and non-segmented negative-sense, positive-sense, and double-stranded RNA viruses infecting both prokaryotic and eukaryotic hosts. The grouping and branching of the viral RdRps in the structure- based phylogenetic tree follow their functional differentiation. The RdRps using protein primer, RNA primer, or self-priming mechanisms have evolved independently of each other, and the RdRps cluster into two large branches based on the used transcription mechanism. -

RNA Sequence of Astrovirus: Distinctive Genomic Organization and a Putative Retrovirus-Like Ribosomal Frameshifting Signal That Directs the Viral Replicase Synthesis

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 90, pp. 10539-10543, November 1993 Microbiology RNA sequence of astrovirus: Distinctive genomic organization and a putative retrovirus-like ribosomal frameshifting signal that directs the viral replicase synthesis BAOMING JIANG*t, STEPHAN S. MONROE*, EUGENE V. KOONINt, SARAH E. STINE*, AND ROGER I. GLASS* *Viral Gastroenteritis Section, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA 30333; and tNational Center for Biotechnology Information, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20894 Communicated by Bernard Fields, July 27, 1993 ABSTRACT The genomic RNA of human astrovirus was In the present study, we have sequenced and analyzed the sequenced and found to contain 6797 nt organized into three entire genomic RNA of H-Ast2§ and compared the sequence open reading frames (la, lb, and 2). A potential ribosomal and genomic structure with those of other positive-strand frameshift site identified in the overlap region of open reading RNA viruses. The results highlight the specific genomic frames la and lb consists ofa "shifty" heptanucleotide and an organization of astroviruses and support their classification RNA stem-loop structure that closely resemble those at the in a separate virus family. gag-pro junction of some retroviruses. This translation frame- shift may result in the suppression of in-frame amber termi- nation at the end of open reading frame la and the synthesis of MATERIALS AND METHODS a nonstructural, fusion polyprotein that contains the putative Cells and Virus. LLCMK2 cells (ATCC CCL 7.1) were protease and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Comparative propagated in Earle's minimal essential medium (MEM) sequence analysis indicated that the protease and polymerase of supplemented with antibiotics-and 10% fetal bovine serum. -

Reverse Genetics of Rotavirus Ulrich Desselbergera,1

COMMENTARY COMMENTARY Reverse genetics of rotavirus Ulrich Desselbergera,1 The genetics of viruses are determined by mutations clarify structure/function relationships of viral genes of their nucleic acid. Mutations can occur spontane- and their protein products and also elucidate complex ously or be produced by physical or chemical means: phenotypes, such as host restriction, pathogenicity, for example, the application of different temperatures and immunogenicity. or mutagens (such as hydroxylamine, nitrous acid, or Kanai et al. (1) have now developed a reverse ge- alkylating agents) that alter the nucleic acid. The clas- netics system for rotaviruses (RVs), which are a major sic way to study virus mutants is to identify a change in cause of acute gastroenteritis in infants and young chil- phenotype compared with the wild-type and to corre- dren and in many mammalian and avian species. World- late this with the mutant genotype (“forward genet- wide RV-associated disease still leads to the death of ics”). Mutants can be studied by complementation, over 200,000 children of <5 y of age per annum (2) recombination, or reassortment analyses. These ap- and thus represents a major public health problem. proaches, although very useful, are cumbersome and The work by Kanai et al. (1) is the most recent ad- prone to problems by often finding several mutations dition to a long list of plasmid-only–based reverse ge- in a genome that are difficult to correlate with a change netics systems of RNA viruses, a selection of which is in phenotype. With the availability of the nucleotide presented in Table 1 (3–13). -

HEPATITIS E the Leading Cause of Acute Viral Hepatitis in the World

HEPATITIS E The Leading Cause of Acute Viral Hepatitis in the World The hepatitis E virus is the leading cause of acute (short-lived) viral hepatitis in the world, and occurs primarily in Africa, Central Asia and Mexico. It accounts for half of all acute hepatitis infection outbreaks in children and adults in areas where it is endemic. Worldwide, hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection is more prevalent than hepatitis A virus infection. Researchers suspect that as many as 20 percent of the world’s population has been infected by the hepatitis E virus. The virus is most common in people between the ages of 15 to 40. In young children, HEV infection often has no symptoms. In adult populations, hepatitis E can wreak havoc. Since the early 1950s, there have been water-borne hepatitis E epidemics reported in New Delhi, India, the former Soviet Union, Nepal, Myanmar (Burma), Algeria, Pakistan, Cote d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast), Bor- neo and in refugee camps in Sudan and Somalia. The virus is transmitted through food or water contaminated by the feces of infected people, but unlike the hepatitis A virus, it is not spread through close person-to-person contact. For some reason that eludes Like hepatitis A, an HEV infection never develops medical researchers, between into a chronic or long-term illness. However, in 15 to 25 percent of pregnant adults, hepatitis E is more severe than hepatitis A, women infected with hepatitis E die, according to the National with death rates reaching between 1 and 2 percent. Centers for Disease Control In contrast, adult death rates from hepatitis A are and Prevention (CDC). -

A Review of Virus Infections of Cetaceans and the Potential Impact of Morbilliviruses, Poxviruses and Papillomaviruses on Host Population Dynamics

DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Published October l l Dis Aquat Org 1 REVIEW A review of virus infections of cetaceans and the potential impact of morbilliviruses, poxviruses and papillomaviruses on host population dynamics Marie-Franqoise Van ~ressern'~~~',Koen Van waerebeekl, Juan Antonio Raga3 'Peruvian Centre for Cetacean Research (CEPEC), Jorge Chdvez 302, Pucusana, Lima 20. Peru 'Department of Vaccinology-Immunology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Liege. Sart Tilman, 4000 Liege, Belgium 3Department of Animal Biology & Cavanilles Research Institute of Biodiversity and Evolutionary Biology, University of Valencia, Dr Moliner 50, 46100 Burjasot, Spain ABSTRACT. Viruses belonging to 9 farmlies have been detected in cetaceans. We critically review the clinical features, pathology and epidemiology of the diseases they cause. Cetacean morbillivirus (fam- ily Paramyxoviridae) induces a serious disease with a high mortality rate and persists in several popu- lation~.It may have long-term effects on the dynamics of cetacean populations either as enzoot~cinfec- tion or recurrent epizootics. The latter presumably have the more profound impact due to removal of sexually mature individuals. Members of the family Poxviridae infect several species of odontocetes, resulting in ring and tattoo skin lesions. Although poxviruses apparently do not induce a high mortality, circumstancial evidence suggests they may be lethal in young animals lacking protective immunity, and thus may negatively affect net recruitment. Papillomaviruses (family Papovaviridae) cause genital warts in at least 3 species of cetaceans. In 10% of male Burmeister's pal-poises Phocoena spinipinnis from Peru, lesions were sufficiently severe to at least hamper, if not impede, copulation. Members of the families Herpesviddae, Orthomyxoviridae and Rhabdov~ridaewere demonstrated in cetaceans suffer- ing serious illnesses, but with the exception of a 'porpoise herpesvirus' their causative role is still tentative.