A Review of Virus Infections of Cetaceans and the Potential Impact of Morbilliviruses, Poxviruses and Papillomaviruses on Host Population Dynamics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bovine Ephemeral Fever in Asia: Recent Status and Research Gaps

viruses Review Bovine Ephemeral Fever in Asia: Recent Status and Research Gaps Fan Lee Epidemiology Division, Animal Health Research Institute; New Taipei City 25158, Taiwan, China; [email protected]; Tel.: +886-2-26212111 Received: 26 March 2019; Accepted: 2 May 2019; Published: 3 May 2019 Abstract: Bovine ephemeral fever is an arthropod-borne viral disease affecting mainly domestic cattle and water buffalo. The etiological agent of this disease is bovine ephemeral fever virus, a member of the genus Ephemerovirus within the family Rhabdoviridae. Bovine ephemeral fever causes economic losses by a sudden drop in milk production in dairy cattle and loss of condition in beef cattle. Although mortality resulting from this disease is usually lower than 1%, it can reach 20% or even higher. Bovine ephemeral fever is distributed across many countries in Asia, Australia, the Middle East, and Africa. Prevention and control of the disease mainly relies on regular vaccination. The impact of bovine ephemeral fever on the cattle industry may be underestimated, and the introduction of bovine ephemeral fever into European countries is possible, similar to the spread of bluetongue virus and Schmallenberg virus. Research on bovine ephemeral fever remains limited and priority of investigation should be given to defining the biological vectors of this disease and identifying virulence determinants. Keywords: Bovine ephemeral fever; Culicoides biting midge; mosquito 1. Introduction Bovine ephemeral fever (BEF), also known as three-day sickness or three-day fever [1], is an arthropod-borne viral disease that mainly strikes cattle and water buffalo. This disease was first recorded in the late 19th century. -

Antiviral Bioactive Compounds of Mushrooms and Their Antiviral Mechanisms: a Review

viruses Review Antiviral Bioactive Compounds of Mushrooms and Their Antiviral Mechanisms: A Review Dong Joo Seo 1 and Changsun Choi 2,* 1 Department of Food Science and Nutrition, College of Health and Welfare and Education, Gwangju University 277 Hyodeok-ro, Nam-gu, Gwangju 61743, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Food and Nutrition, School of Food Science and Technology, College of Biotechnology and Natural Resources, Chung-Ang University, 4726 Seodongdaero, Daeduck-myun, Anseong-si, Gyeonggi-do 17546, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-31-670-4589; Fax: +82-31-676-8741 Abstract: Mushrooms are used in their natural form as a food supplement and food additive. In addition, several bioactive compounds beneficial for human health have been derived from mushrooms. Among them, polysaccharides, carbohydrate-binding protein, peptides, proteins, enzymes, polyphenols, triterpenes, triterpenoids, and several other compounds exert antiviral activity against DNA and RNA viruses. Their antiviral targets were mostly virus entry, viral genome replication, viral proteins, and cellular proteins and influenced immune modulation, which was evaluated through pre-, simultaneous-, co-, and post-treatment in vitro and in vivo studies. In particular, they treated and relieved the viral diseases caused by herpes simplex virus, influenza virus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Some mushroom compounds that act against HIV, influenza A virus, and hepatitis C virus showed antiviral effects comparable to those of antiviral drugs. Therefore, bioactive compounds from mushrooms could be candidates for treating viral infections. Citation: Seo, D.J.; Choi, C. Antiviral Bioactive Compounds of Mushrooms Keywords: mushroom; bioactive compound; virus; infection; antiviral mechanism and Their Antiviral Mechanisms: A Review. -

Intracellular Trafficking of HBV Particles

cells Review Intracellular Trafficking of HBV Particles Bingfu Jiang 1 and Eberhard Hildt 1,2,* 1 Department of Virology, Paul-Ehrlich-Institut, D-63225 Langen, Germany; [email protected] 2 German Center for Infection Research (DZIF), TTU Hepatitis, Marburg-Gießen-Langen, D63225 Langen, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-61-0377-2140 Received: 12 August 2020; Accepted: 2 September 2020; Published: 2 September 2020 Abstract: The human hepatitis B virus (HBV), that is causative for more than 240 million cases of chronic liver inflammation (hepatitis), is an enveloped virus with a partially double-stranded DNA genome. After virion uptake by receptor-mediated endocytosis, the viral nucleocapsid is transported towards the nuclear pore complex. In the nuclear basket, the nucleocapsid disassembles. The viral genome that is covalently linked to the viral polymerase, which harbors a bipartite NLS, is imported into the nucleus. Here, the partially double-stranded DNA genome is converted in a minichromosome-like structure, the covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA). The DNA virus HBV replicates via a pregenomic RNA (pgRNA)-intermediate that is reverse transcribed into DNA. HBV-infected cells release apart from the infectious viral parrticle two forms of non-infectious subviral particles (spheres and filaments), which are assembled by the surface proteins but lack any capsid and nucleic acid. In addition, naked capsids are released by HBV replicating cells. Infectious viral particles and filaments are released via multivesicular bodies; spheres are secreted by the classic constitutive secretory pathway. The release of naked capsids is still not fully understood, autophagosomal processes are discussed. This review describes intracellular trafficking pathways involved in virus entry, morphogenesis and release of (sub)viral particles. -

Discovery of a Highly Divergent Hepadnavirus in Shrews from China

Virology 531 (2019) 162–170 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Virology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/virology Discovery of a highly divergent hepadnavirus in shrews from China T Fang-Yuan Niea,b,1, Jun-Hua Tianc,1, Xian-Dan Lind,1, Bin Yuc, Jian-Guang Xinge, Jian-Hai Caof, ⁎ ⁎⁎ Edward C. Holmesg,h, Runlin Z. Maa, , Yong-Zhen Zhangb,h, a State Key Laboratory of Molecular Developmental Biology, Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China b State Key Laboratory for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control; Collaborative Innovation Center for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases; Department of Zoonoses, National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Changping, Beijing, China c Wuhan Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Wuhan, China d Wenzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province, China e Wencheng Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Wencheng, Zhejiang Province, China f Longwan Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Longwan District, Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province, China g Marie Bashir Institute for Infectious Diseases and Biosecurity, Charles Perkins Centre, School of Life and Environmental Sciences and Sydney Medical School, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia h Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center & Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Fudan University, Shanghai, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Limited sampling means that relatively little is known about the diversity and evolutionary history of mam- Hepadnaviruses malian members of the Hepadnaviridae (genus Orthohepadnavirus). An important case in point are shrews, the Shrews fourth largest group of mammals, but for which there is limited knowledge on the role they play in viral evo- Phylogeny lution and emergence. -

Detection of Astrovirus in a Cow with Neurological Signs by Nanopore Technology, Italy

viruses Article Detection of Astrovirus in a Cow with Neurological Signs by Nanopore Technology, Italy Guendalina Zaccaria 1, Alessio Lorusso 1,*, Melanie M. Hierweger 2,3, Daniela Malatesta 1, Sabrina VP Defourny 1, Franco Ruggeri 4, Cesare Cammà 1 , Pasquale Ricci 4, Marco Di Domenico 1 , Antonio Rinaldi 1, Nicola Decaro 5 , Nicola D’Alterio 1, Antonio Petrini 1 , Torsten Seuberlich 3 and Maurilia Marcacci 1,5 1 Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale dell’Abruzzo e Molise, 64100 Teramo, Italy; [email protected] (G.Z.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (S.V.D.); [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (M.D.D.); [email protected] (A.R.); [email protected] (N.D.); [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (M.M.) 2 NeuroCenter, Department of Clinical Research and Veterinary Public Health, University of Bern, 3012 Bern, Switzerland; [email protected] 3 Graduate School for Cellular and Biomedical Sciences, University of Bern, 3012 Bern, Switzerland; [email protected] 4 Unità Operativa Complessa Servizio di Sanità Animale, ASL Pescara, 65100 Pescara, Italy; [email protected] (F.R.); [email protected] (P.R.) 5 Dipartimento di Medicina Veterinaria, Università degli Studi di Bari, 70010 Valenzano, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0861-332440 Received: 23 April 2020; Accepted: 9 May 2020; Published: 11 May 2020 Abstract: In this study, starting from nucleic acids purified from the brain tissue, Nanopore technology was used to identify the etiological agent of severe neurological signs observed in a cow which was immediately slaughtered. -

Detection of Respiratory Viruses and Subtype Identification of Inffuenza a Viruses by Greenechipresp Oligonucleotide Microarray

JOURNAL OF CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY, Aug. 2007, p. 2359–2364 Vol. 45, No. 8 0095-1137/07/$08.00ϩ0 doi:10.1128/JCM.00737-07 Copyright © 2007, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved. Detection of Respiratory Viruses and Subtype Identification of Influenza A Viruses by GreeneChipResp Oligonucleotide Microarrayᰔ† Phenix-Lan Quan,1‡ Gustavo Palacios,1‡ Omar J. Jabado,1 Sean Conlan,1 David L. Hirschberg,2 Francisco Pozo,3 Philippa J. M. Jack,4 Daniel Cisterna,5 Neil Renwick,1 Jeffrey Hui,1 Andrew Drysdale,1 Rachel Amos-Ritchie,4 Elsa Baumeister,5 Vilma Savy,5 Kelly M. Lager,6 Ju¨rgen A. Richt,6 David B. Boyle,4 Adolfo Garcı´a-Sastre,7 Inmaculada Casas,3 Pilar Perez-Bren˜a,3 Thomas Briese,1 and W. Ian Lipkin1* Jerome L. and Dawn Greene Infectious Disease Laboratory, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York1; Stanford School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California2; Centro Nacional de Microbiologia, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain3; CSIRO Livestock Industries, Australian Animal Health Laboratory, Victoria, Australia4; Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Infecciosas, ANLIS Dr. Carlos G. Malbra´n, Buenos Aires, Argentina5; National Animal Disease Center, USDA, Ames, Iowa6; and Department of Microbiology and Emerging Pathogens Institute, 7 Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York Downloaded from Received 4 April 2007/Returned for modification 15 May 2007/Accepted 21 May 2007 Acute respiratory infections are significant causes of morbidity, mortality, and economic burden worldwide. An accurate, early differential diagnosis may alter individual clinical management as well as facilitate the recognition of outbreaks that have implications for public health. -

Norovirus Infectious Agent Information Sheet

Norovirus Infectious Agent Information Sheet Introduction Noroviruses are non-enveloped (naked) RNA viruses with icosahedral nucleocapsid symmetry. The norovirus genome consists of (+) ssRNA, containing three open reading frames that encode for proteins required for transcription, replication, and assembly. There are five norovirus genogroups (GI-GV), and only GI, GII, and GIV infect humans. Norovirus belongs to the Caliciviridae family of viruses, and has had past names including, Norwalk virus and “winter-vomiting” disease. Epidemiology and Clinical Significance Noroviruses are considered the most common cause of outbreaks of non-bacterial gastroenteritis worldwide, are the leading cause of foodborne illness in the United States (58%), and account for 26% of hospitalizations and 10% of deaths associated with food consumption. Salad ingredients, fruit, and oysters are the most implicated in norovirus outbreaks. Aside from food and water, Noroviruses can also be transmitted by person to person contact and contact with environmental surfaces. The rapid spread of secondary infections occurs in areas where a large population is enclosed within a static environment, such as cruise ships, military bases, and institutions. Symptoms typically last for 24 to 48 hours, but can persist up to 96 hours in the immunocompromised. Pathogenesis, Immunity, Treatment and Prevention Norovirus is highly infectious due to low infecting dose, high excretion level (105 to 107 copies/mg stool), and continual shedding after clinical recovery (>1 month). The norovirus genome undergoes frequent change due to mutation and recombination, which increases its prevalence. Studies suggest that acquired immunity only last 6 months after infection. Gastroenteritis, an inflammation of the stomach and small and large intestines, is caused by norovirus infection. -

Modelling Cetacean Morbillivirus Outbreaks in an Endangered Killer Whale Population T ⁎ Michael N

Biological Conservation 242 (2020) 108398 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Modelling cetacean morbillivirus outbreaks in an endangered killer whale population T ⁎ Michael N. Weissa,b, , Daniel W. Franksc, Kenneth C. Balcombb, David K. Ellifritb, Matthew J. Silkd, Michael A. Cantd, Darren P. Crofta a Centre for Research in Animal Behaviour, University of Exeter, Exeter EX4 4QG, UK b Center for Whale Research, Friday Harbor 98250, WA, USA c Department of Biology and Department of Computer Science, University of York, York YO10 5DD, UK d Centre for Ecology and Conservation, University of Exeter in Cornwall, Penryn TR10 9FE, UK ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The emergence of novel diseases represents a major hurdle for the recovery of endangered populations, and in Social network some cases may even present the threat of extinction. In recent years, epizootics of infectious diseases have Epidemic modelling emerged as a major threat to marine mammal populations, particularly group-living odontocetes. However, little Orcinus orca research has explored the potential consequences of novel pathogens in endangered cetacean populations. Here, SRKW we present the first study predicting the spread of infectious disease over the social network of an entire free- Vaccination ranging cetacean population, the southern resident killer whale community (SRKW). Utilizing 5 years of detailed data on close contacts between individuals, we build a fine-scale social network describing potential transmis- sion pathways in this population. We then simulate the spread of cetacean morbillivirus (CeMV) over this network. Our analysis suggests that the SRKW population is highly vulnerable to CeMV. -

Molecular Identification and Genetic Characterization of Cetacean Herpesviruses and Porpoise Morbillivirus

MOLECULAR IDENTIFICATION AND GENETIC CHARACTERIZATION OF CETACEAN HERPESVIRUSES AND PORPOISE MORBILLIVIRUS By KARA ANN SMOLAREK BENSON A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2005 Copyright 2005 by Kara Ann Smolarek Benson I dedicate this to my best friend and husband, Brock, who has always believed in me. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost I thank my mentor, Dr. Carlos Romero, who once told me that love is fleeting but herpes is forever. He welcomed me into his lab with very little experience and I have learned so much from him over the past few years. Without his excellent guidance, this project would not have been possible. I thank my parents, Dave and Judy Smolarek, for their continual love and support. They taught me the importance of hard work and a great education, and always believed that I would be successful in life. I would like to thank Dr. Tom Barrett for the wonderful opportunity to study porpoise morbillivirus in his laboratory at the Institute for Animal Health in England, and Dr. Romero for making the trip possible. I especially thank Dr. Ashley Banyard for helping me accomplish all the objectives of the project, and all the wonderful people at the IAH for making a Yankee feel right at home in the UK. I thank Alexa Bracht and Rebecca Woodruff who have been with me in Dr. Romero’s lab since the beginning. Their continuous friendship and encouragement have kept me sane even in the most hectic of times. -

Viruses in Transplantation - Not Always Enemies

Viruses in transplantation - not always enemies Virome and transplantation ECCMID 2018 - Madrid Prof. Laurent Kaiser Head Division of Infectious Diseases Laboratory of Virology Geneva Center for Emerging Viral Diseases University Hospital of Geneva ESCMID eLibrary © by author Conflict of interest None ESCMID eLibrary © by author The human virome: definition? Repertoire of viruses found on the surface of/inside any body fluid/tissue • Eukaryotic DNA and RNA viruses • Prokaryotic DNA and RNA viruses (phages) 25 • The “main” viral community (up to 10 bacteriophages in humans) Haynes M. 2011, Metagenomic of the human body • Endogenous viral elements integrated into host chromosomes (8% of the human genome) • NGS is shaping the definition Rascovan N et al. Annu Rev Microbiol 2016;70:125-41 Popgeorgiev N et al. Intervirology 2013;56:395-412 Norman JM et al. Cell 2015;160:447-60 ESCMID eLibraryFoxman EF et al. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011;9:254-64 © by author Viruses routinely known to cause diseases (non exhaustive) Upper resp./oropharyngeal HSV 1 Influenza CNS Mumps virus Rhinovirus JC virus RSV Eye Herpes viruses Parainfluenza HSV Measles Coronavirus Adenovirus LCM virus Cytomegalovirus Flaviviruses Rabies HHV6 Poliovirus Heart Lower respiratory HTLV-1 Coxsackie B virus Rhinoviruses Parainfluenza virus HIV Coronaviruses Respiratory syncytial virus Parainfluenza virus Adenovirus Respiratory syncytial virus Coronaviruses Gastro-intestinal Influenza virus type A and B Human Bocavirus 1 Adenovirus Hepatitis virus type A, B, C, D, E Those that cause -

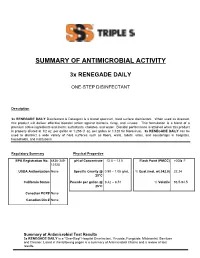

Summary of Antimicrobial Activity

SUMMARY OF ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY 3x RENEGADE DAILY ONE-STEP DISINFECTANT Description 3x RENEGADE DAILY Disinfectant & Detergent is a broad spectrum, hard surface disinfectant. When used as directed, this product will deliver effective biocidal action against bacteria, fungi, and viruses. This formulation is a blend of a premium active ingredients and inerts: surfactants, chelates, and water. Biocidal performance is attained when this product is properly diluted at 1/2 oz. per gallon or 1:256 (1 oz. per gallon or 1:128 for Norovirus). 3x RENEGADE DAILY can be used to disinfect a wide variety of hard surfaces such as floors, walls, toilets, sinks, and countertops in hospitals, households, and institutions. Regulatory Summary Physical Properties EPA Registration No. 6836-349- pH of Concentrate 12.0 – 13.5 Flash Point (PMCC) >200 F 12120 USDA Authorization None Specific Gravity @ 0.98 – 1.05 g/mL % Quat (mol. wt.342.0) 22.24 25°C California Status Pounds per gallon @ 8.42 – 8.51 % Volatile 93.5-94.5 25°C Canadian PCP# None Canadian Din # None Summary of Antimicrobial Test Results 3x RENEGADE DAILY is a "One-Step" Hospital Disinfectant, Virucide, Fungicide, Mildewstat, Sanitizer and Cleaner. Listed in the following pages is a summary of Antimicrobial Claims and a review of test results. Claim: Contact time: Organic Soil: Water Conditions: Disinfectant Varies 5% 250ppm as CaCO3 Test Method: AOAC Germicidal Spray Test Organism Contact Dilution Time (Min) 868 ppm (1/2oz. per Acinetobacter baumannii 3 Gal) Bordetella bronchiseptica 3 868 ppm Bordetella pertussis 3 868 ppm Campylobacter jejuni 3 868 ppm Enterobacter aerogenes 3 1736 PPM (1 oz per Gal) Enterococcus faecalis 3 868 ppm Enterococcus faecalis - Vancomycin resistant [VRE] 3 868 ppm Escherichia coli 3 868 ppm Escherichia coli [O157:H7] 3 868 ppm Escherichia coli ESBL – Extended spectrum beta- 868 ppm 10 lactamase containing E. -

A Scoping Review of Viral Diseases in African Ungulates

veterinary sciences Review A Scoping Review of Viral Diseases in African Ungulates Hendrik Swanepoel 1,2, Jan Crafford 1 and Melvyn Quan 1,* 1 Vectors and Vector-Borne Diseases Research Programme, Department of Veterinary Tropical Disease, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0110, South Africa; [email protected] (H.S.); [email protected] (J.C.) 2 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Institute of Tropical Medicine, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-12-529-8142 Abstract: (1) Background: Viral diseases are important as they can cause significant clinical disease in both wild and domestic animals, as well as in humans. They also make up a large proportion of emerging infectious diseases. (2) Methods: A scoping review of peer-reviewed publications was performed and based on the guidelines set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews. (3) Results: The final set of publications consisted of 145 publications. Thirty-two viruses were identified in the publications and 50 African ungulates were reported/diagnosed with viral infections. Eighteen countries had viruses diagnosed in wild ungulates reported in the literature. (4) Conclusions: A comprehensive review identified several areas where little information was available and recommendations were made. It is recommended that governments and research institutions offer more funding to investigate and report viral diseases of greater clinical and zoonotic significance. A further recommendation is for appropriate One Health approaches to be adopted for investigating, controlling, managing and preventing diseases. Diseases which may threaten the conservation of certain wildlife species also require focused attention.