Discovery of a Highly Divergent Hepadnavirus in Shrews from China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hepatitis Virus in Long-Fingered Bats, Myanmar

DISPATCHES Myanmar; the counties are adjacent to Yunnan Province, Hepatitis Virus People’s Republic of China. The bats covered 6 species: Miniopterus fuliginosus (n = 640), Hipposideros armiger in Long-Fingered (n = 8), Rhinolophus ferrumequinum (n = 176), Myotis chi- nensis (n = 11), Megaderma lyra (n = 6), and Hipposideros Bats, Myanmar fulvus (n = 12). All bat tissue samples were subjected to vi- Biao He,1 Quanshui Fan,1 Fanli Yang, ral metagenomic analysis (unpublished data). The sampling Tingsong Hu, Wei Qiu, Ye Feng, Zuosheng Li, of bats for this study was approved by the Administrative Yingying Li, Fuqiang Zhang, Huancheng Guo, Committee on Animal Welfare of the Institute of Military Xiaohuan Zou, and Changchun Tu Veterinary, Academy of Military Medical Sciences, China. We used PCR to further study the prevalence of or- During an analysis of the virome of bats from Myanmar, thohepadnavirus in the 6 bat species; the condition of the a large number of reads were annotated to orthohepadnavi- samples made serologic assay and pathology impracticable. ruses. We present the full genome sequence and a morpho- Viral DNA was extracted from liver tissue of each of the logical analysis of an orthohepadnavirus circulating in bats. 853 bats by using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, This virus is substantially different from currently known Hilden, Germany). To detect virus in the samples, we con- members of the genus Orthohepadnavirus and represents ducted PCR by using the TaKaRa PCR Kit (TaKaRa, Da- a new species. lian, China) with a pair of degenerate pan-orthohepadnavi- rus primers (sequences available upon request). The PCR he family Hepadnaviridae comprises 2 genera (Ortho- reaction was as follows: 45 cycles of denaturation at 94°C Thepadnavirus and Avihepadnavirus), and viruses clas- for 30 s, annealing at 54°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for sified within these genera have a narrow host range. -

Intracellular Trafficking of HBV Particles

cells Review Intracellular Trafficking of HBV Particles Bingfu Jiang 1 and Eberhard Hildt 1,2,* 1 Department of Virology, Paul-Ehrlich-Institut, D-63225 Langen, Germany; [email protected] 2 German Center for Infection Research (DZIF), TTU Hepatitis, Marburg-Gießen-Langen, D63225 Langen, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-61-0377-2140 Received: 12 August 2020; Accepted: 2 September 2020; Published: 2 September 2020 Abstract: The human hepatitis B virus (HBV), that is causative for more than 240 million cases of chronic liver inflammation (hepatitis), is an enveloped virus with a partially double-stranded DNA genome. After virion uptake by receptor-mediated endocytosis, the viral nucleocapsid is transported towards the nuclear pore complex. In the nuclear basket, the nucleocapsid disassembles. The viral genome that is covalently linked to the viral polymerase, which harbors a bipartite NLS, is imported into the nucleus. Here, the partially double-stranded DNA genome is converted in a minichromosome-like structure, the covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA). The DNA virus HBV replicates via a pregenomic RNA (pgRNA)-intermediate that is reverse transcribed into DNA. HBV-infected cells release apart from the infectious viral parrticle two forms of non-infectious subviral particles (spheres and filaments), which are assembled by the surface proteins but lack any capsid and nucleic acid. In addition, naked capsids are released by HBV replicating cells. Infectious viral particles and filaments are released via multivesicular bodies; spheres are secreted by the classic constitutive secretory pathway. The release of naked capsids is still not fully understood, autophagosomal processes are discussed. This review describes intracellular trafficking pathways involved in virus entry, morphogenesis and release of (sub)viral particles. -

Virus Particle Structures

Virus Particle Structures Virus Particle Structures Palmenberg, A.C. and Sgro, J.-Y. COLOR PLATE LEGENDS These color plates depict the relative sizes and comparative virion structures of multiple types of viruses. The renderings are based on data from published atomic coordinates as determined by X-ray crystallography. The international online repository for 3D coordinates is the Protein Databank (www.rcsb.org/pdb/), maintained by the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB). The VIPER web site (mmtsb.scripps.edu/viper), maintains a parallel collection of PDB coordinates for icosahedral viruses and additionally offers a version of each data file permuted into the same relative 3D orientation (Reddy, V., Natarajan, P., Okerberg, B., Li, K., Damodaran, K., Morton, R., Brooks, C. and Johnson, J. (2001). J. Virol., 75, 11943-11947). VIPER also contains an excellent repository of instructional materials pertaining to icosahedral symmetry and viral structures. All images presented here, except for the filamentous viruses, used the standard VIPER orientation along the icosahedral 2-fold axis. With the exception of Plate 3 as described below, these images were generated from their atomic coordinates using a novel radial depth-cue colorization technique and the program Rasmol (Sayle, R.A., Milner-White, E.J. (1995). RASMOL: biomolecular graphics for all. Trends Biochem Sci., 20, 374-376). First, the Temperature Factor column for every atom in a PDB coordinate file was edited to record a measure of the radial distance from the virion center. The files were rendered using the Rasmol spacefill menu, with specular and shadow options according to the Van de Waals radius of each atom. -

And Giant Guitarfish (Rhynchobatus Djiddensis)

VIRAL DISCOVERY IN BLUEGILL SUNFISH (LEPOMIS MACROCHIRUS) AND GIANT GUITARFISH (RHYNCHOBATUS DJIDDENSIS) BY HISTOPATHOLOGY EVALUATION, METAGENOMIC ANALYSIS AND NEXT GENERATION SEQUENCING by JENNIFER ANNE DILL (Under the Direction of Alvin Camus) ABSTRACT The rapid growth of aquaculture production and international trade in live fish has led to the emergence of many new diseases. The introduction of novel disease agents can result in significant economic losses, as well as threats to vulnerable wild fish populations. Losses are often exacerbated by a lack of agent identification, delay in the development of diagnostic tools and poor knowledge of host range and susceptibility. Examples in bluegill sunfish (Lepomis macrochirus) and the giant guitarfish (Rhynchobatus djiddensis) will be discussed here. Bluegill are popular freshwater game fish, native to eastern North America, living in shallow lakes, ponds, and slow moving waterways. Bluegill experiencing epizootics of proliferative lip and skin lesions, characterized by epidermal hyperplasia, papillomas, and rarely squamous cell carcinoma, were investigated in two isolated poopulations. Next generation genomic sequencing revealed partial DNA sequences of an endogenous retrovirus and the entire circular genome of a novel hepadnavirus. Giant Guitarfish, a rajiform elasmobranch listed as ‘vulnerable’ on the IUCN Red List, are found in the tropical Western Indian Ocean. Proliferative skin lesions were observed on the ventrum and caudal fin of a juvenile male quarantined at a public aquarium following international shipment. Histologically, lesions consisted of papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia with myriad large, amphophilic, intranuclear inclusions. Deep sequencing and metagenomic analysis produced the complete genomes of two novel DNA viruses, a typical polyomavirus and a second unclassified virus with a 20 kb genome tentatively named Colossomavirus. -

Virus Classification Tables V2.Vd.Xlsx

DNA Virus Classification Table DNA Virus Family Genera (Subfamily) Typical Species Genetic material Capsid Envelope Disease in Humans Diseases in other Species Adenoviridae Mastadenovirus Adenoviruses 1‐47 dsDNA Icosahedral Naked Respiratory illness; conjunctivitis, Canine hepatitis, respiratory illness in horses, gastroenteritis, tonsillitis, meningitis, cystitis cattle, pigs, sheep, goats, sea lions, birds dogs, squirrel enteritis Anelloviridae Torqueviruses Alpha‐Zeta Torqueviruses (‐)ssDNA Icosahedral Naked Hepatitis, lupus, pulmonary, myopathy, Chimpanzee, pig, cow, sheep, tree shrews, multiple sclerosis; 90% of humans infected pigs, cats, sea lions and chickens worldwide Asfarviridae Asfivirus African Swine fever virus dsDNA Icosahedral Enveloped African swine fever Arthropod (tick) transmission or ingestion; hemorrhagic fever in warthogs, pigs Baculoviridae Baculovirus Alpha‐Gamma Baculoviruses dsDNA Stick shaped Occluded or Enveloped none identified Arthropods, Lepidoptera, crustaceans Circoviridae Circovirus Porcine circovirus 1 ssDNA Icosahedral Naked none identified Birds, pigs, dogs; bats; rodents; causes post‐ weaning multisystem wasting syndrome, chicken anemia Circoviridae Cyclovirus Human cyclovirus 1 ssDNA Icosahedral Naked Cyclovirus Vietnam encephalitis Encephalitis; infects multiple species including birds, mammals, insects Hepadnaviridae Orthohepadnavirus Hepatitis B virus partially ssDNA Icosahedral Enveloped Hepatitis B virus; Cirrhosis, Hepatocellular Hepatitis in ducks, squirrels, primates, herons carcinoma Herpesviridae -

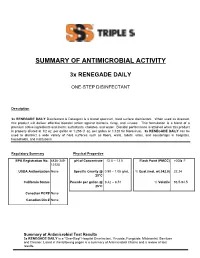

Summary of Antimicrobial Activity

SUMMARY OF ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY 3x RENEGADE DAILY ONE-STEP DISINFECTANT Description 3x RENEGADE DAILY Disinfectant & Detergent is a broad spectrum, hard surface disinfectant. When used as directed, this product will deliver effective biocidal action against bacteria, fungi, and viruses. This formulation is a blend of a premium active ingredients and inerts: surfactants, chelates, and water. Biocidal performance is attained when this product is properly diluted at 1/2 oz. per gallon or 1:256 (1 oz. per gallon or 1:128 for Norovirus). 3x RENEGADE DAILY can be used to disinfect a wide variety of hard surfaces such as floors, walls, toilets, sinks, and countertops in hospitals, households, and institutions. Regulatory Summary Physical Properties EPA Registration No. 6836-349- pH of Concentrate 12.0 – 13.5 Flash Point (PMCC) >200 F 12120 USDA Authorization None Specific Gravity @ 0.98 – 1.05 g/mL % Quat (mol. wt.342.0) 22.24 25°C California Status Pounds per gallon @ 8.42 – 8.51 % Volatile 93.5-94.5 25°C Canadian PCP# None Canadian Din # None Summary of Antimicrobial Test Results 3x RENEGADE DAILY is a "One-Step" Hospital Disinfectant, Virucide, Fungicide, Mildewstat, Sanitizer and Cleaner. Listed in the following pages is a summary of Antimicrobial Claims and a review of test results. Claim: Contact time: Organic Soil: Water Conditions: Disinfectant Varies 5% 250ppm as CaCO3 Test Method: AOAC Germicidal Spray Test Organism Contact Dilution Time (Min) 868 ppm (1/2oz. per Acinetobacter baumannii 3 Gal) Bordetella bronchiseptica 3 868 ppm Bordetella pertussis 3 868 ppm Campylobacter jejuni 3 868 ppm Enterobacter aerogenes 3 1736 PPM (1 oz per Gal) Enterococcus faecalis 3 868 ppm Enterococcus faecalis - Vancomycin resistant [VRE] 3 868 ppm Escherichia coli 3 868 ppm Escherichia coli [O157:H7] 3 868 ppm Escherichia coli ESBL – Extended spectrum beta- 868 ppm 10 lactamase containing E. -

The Approved List of Biological Agents Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens Health and Safety Executive

The Approved List of biological agents Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens Health and Safety Executive © Crown copyright 2021 First published 2000 Second edition 2004 Third edition 2013 Fourth edition 2021 You may reuse this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view the licence visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/ open-government-licence/, write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email [email protected]. Some images and illustrations may not be owned by the Crown so cannot be reproduced without permission of the copyright owner. Enquiries should be sent to [email protected]. The Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations 2002 refer to an ‘approved classification of a biological agent’, which means the classification of that agent approved by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE). This list is approved by HSE for that purpose. This edition of the Approved List has effect from 12 July 2021. On that date the previous edition of the list approved by the Health and Safety Executive on the 1 July 2013 will cease to have effect. This list will be reviewed periodically, the next review is due in February 2022. The Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens (ACDP) prepares the Approved List included in this publication. ACDP advises HSE, and Ministers for the Department of Health and Social Care and the Department for the Environment, Food & Rural Affairs and their counterparts under devolution in Scotland, Wales & Northern Ireland, as required, on all aspects of hazards and risks to workers and others from exposure to pathogens. -

Risk Groups: Viruses (C) 1988, American Biological Safety Association

Rev.: 1.0 Risk Groups: Viruses (c) 1988, American Biological Safety Association BL RG RG RG RG RG LCDC-96 Belgium-97 ID Name Viral group Comments BMBL-93 CDC NIH rDNA-97 EU-96 Australia-95 HP AP (Canada) Annex VIII Flaviviridae/ Flavivirus (Grp 2 Absettarov, TBE 4 4 4 implied 3 3 4 + B Arbovirus) Acute haemorrhagic taxonomy 2, Enterovirus 3 conjunctivitis virus Picornaviridae 2 + different 70 (AHC) Adenovirus 4 Adenoviridae 2 2 (incl animal) 2 2 + (human,all types) 5 Aino X-Arboviruses 6 Akabane X-Arboviruses 7 Alastrim Poxviridae Restricted 4 4, Foot-and- 8 Aphthovirus Picornaviridae 2 mouth disease + viruses 9 Araguari X-Arboviruses (feces of children 10 Astroviridae Astroviridae 2 2 + + and lambs) Avian leukosis virus 11 Viral vector/Animal retrovirus 1 3 (wild strain) + (ALV) 3, (Rous 12 Avian sarcoma virus Viral vector/Animal retrovirus 1 sarcoma virus, + RSV wild strain) 13 Baculovirus Viral vector/Animal virus 1 + Togaviridae/ Alphavirus (Grp 14 Barmah Forest 2 A Arbovirus) 15 Batama X-Arboviruses 16 Batken X-Arboviruses Togaviridae/ Alphavirus (Grp 17 Bebaru virus 2 2 2 2 + A Arbovirus) 18 Bhanja X-Arboviruses 19 Bimbo X-Arboviruses Blood-borne hepatitis 20 viruses not yet Unclassified viruses 2 implied 2 implied 3 (**)D 3 + identified 21 Bluetongue X-Arboviruses 22 Bobaya X-Arboviruses 23 Bobia X-Arboviruses Bovine 24 immunodeficiency Viral vector/Animal retrovirus 3 (wild strain) + virus (BIV) 3, Bovine Bovine leukemia 25 Viral vector/Animal retrovirus 1 lymphosarcoma + virus (BLV) virus wild strain Bovine papilloma Papovavirus/ -

Arenaviridae Astroviridae Filoviridae Flaviviridae Hantaviridae

Hantaviridae 0.7 Filoviridae 0.6 Picornaviridae 0.3 Wenling red spikefish hantavirus Rhinovirus C Ahab virus * Possum enterovirus * Aronnax virus * * Wenling minipizza batfish hantavirus Wenling filefish filovirus Norway rat hunnivirus * Wenling yellow goosefish hantavirus Starbuck virus * * Porcine teschovirus European mole nova virus Human Marburg marburgvirus Mosavirus Asturias virus * * * Tortoise picornavirus Egyptian fruit bat Marburg marburgvirus Banded bullfrog picornavirus * Spanish mole uluguru virus Human Sudan ebolavirus * Black spectacled toad picornavirus * Kilimanjaro virus * * * Crab-eating macaque reston ebolavirus Equine rhinitis A virus Imjin virus * Foot and mouth disease virus Dode virus * Angolan free-tailed bat bombali ebolavirus * * Human cosavirus E Seoul orthohantavirus Little free-tailed bat bombali ebolavirus * African bat icavirus A Tigray hantavirus Human Zaire ebolavirus * Saffold virus * Human choclo virus *Little collared fruit bat ebolavirus Peleg virus * Eastern red scorpionfish picornavirus * Reed vole hantavirus Human bundibugyo ebolavirus * * Isla vista hantavirus * Seal picornavirus Human Tai forest ebolavirus Chicken orivirus Paramyxoviridae 0.4 * Duck picornavirus Hepadnaviridae 0.4 Bildad virus Ned virus Tiger rockfish hepatitis B virus Western African lungfish picornavirus * Pacific spadenose shark paramyxovirus * European eel hepatitis B virus Bluegill picornavirus Nemo virus * Carp picornavirus * African cichlid hepatitis B virus Triplecross lizardfish paramyxovirus * * Fathead minnow picornavirus -

Inhibitory Effect of CPXV012 Peptide on Enveloped and Non-Enveloped Viruses of Different Families

Supplementary Materials Table 1 - Inhibitory effect of CPXV012 peptide on enveloped and non-enveloped viruses of different families Virus Family Genome Envelope Inhibition MVA Poxviridae dsDNA yes yes VACV-WR Poxviridae dsDNA yes yes CPXV-BR Poxviridae dsDNA yes yes HSV-1 Herpesviridae dsDNA yes yes HBV Hepadnaviridae dsDNA-RT yes yes HIV-1 Retroviridae ssRNA-RT yes yes RVFV Bunyaviridae ssRNA yes yes Measles Paramyxoviridae ssRNA yes no VSV Rhabdoviridae ssRNA yes no Adenovirus Adenoviridae dsDNA no no CVB3 Picornaviridae ssRNA no no MVA: Modified Vaccinia virus Ankara; VACV-WR: vaccinia virus strain Western Reserve; CPXV-BR: cowpox virus strain Brighton Red; HSV-1: herpes simplex virus-1; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; RVFV: Rift Valley fever virus; VSV: vesicular stomatitis virus; CVB3: coxsackie virus B3. A B 140 0.6 ) l 120 ro t 100 on 0.4 c g f 80 µ / o 60 % NR ( 0.2 1 - 40 T S 20 W 0 0.0 O 5 0 0 0 5 0 0 0 S 2 5 0 0 O 2 5 0 0 1 2 S 1 2 M M D D CPXV012 peptide [ g/mL] CPXV012 peptide [ g/mL] C ) . 30000 U . A ( e u 20000 l b r e t i t 10000 ll e C 0 0 50 100 150 200 CPXV012 peptide [ g/mL] Huh7.5 Vero Figure S1: CPXV012 peptide does not affect cell viability. (A-C) Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of peptide or DMSO as vehicle control. S.E.M. of three independent experiments is shown. (A) Viability of MJS cells was measured by WST-1 assay or (B) Neutral Red uptake. -

Mechanism of Hepatitis B Virus Cccdna Formation

viruses Review Mechanism of Hepatitis B Virus cccDNA Formation Lei Wei and Alexander Ploss * 110 Lewis Thomas Laboratory, Department of Molecular Biology, Princeton University, Washington Road, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-609-258-7128 Abstract: Hepatitis B virus (HBV) remains a major medical problem affecting at least 257 million chronically infected patients who are at risk of developing serious, frequently fatal liver diseases. HBV is a small, partially double-stranded DNA virus that goes through an intricate replication cycle in its native cellular environment: human hepatocytes. A critical step in the viral life-cycle is the conversion of relaxed circular DNA (rcDNA) into covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA), the latter being the major template for HBV gene transcription. For this conversion, HBV relies on multiple host factors, as enzymes capable of catalyzing the relevant reactions are not encoded in the viral genome. Combinations of genetic and biochemical approaches have produced findings that provide a more holistic picture of the complex mechanism of HBV cccDNA formation. Here, we review some of these studies that have helped to provide a comprehensive picture of rcDNA to cccDNA conversion. Mechanistic insights into this critical step for HBV persistence hold the key for devising new therapies that will lead not only to viral suppression but to a cure. Keywords: hepatitis B virus; HBV; viral replication; cccDNA biogenesis; rcDNA; DNA repair Citation: Wei, L.; Ploss, A. 1. Overview of HBV Life Cycle and cccDNA Biogenesis Mechanism of Hepatitis B Virus cccDNA Formation. Viruses 2021, 13, The hepatotropic HBV belongs to the Hepadnaviridae family and is a blood-borne 1463. -

Downloaded from Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly (TSA) Database on 29 November 2020 (Ftp://Ftp.Ddbj.Nig.Ac.Jp/Ddbj Database/Tsa/, Table S3)

viruses Article Discovery and Characterization of Actively Replicating DNA and Retro-Transcribing Viruses in Lower Vertebrate Hosts Based on RNA Sequencing Xin-Xin Chen, Wei-Chen Wu and Mang Shi * School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University, Shenzhen 518107, China; [email protected] (X.-X.C.); [email protected] (W.-C.W.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In a previous study, a metatranscriptomics survey of RNA viruses in several important lower vertebrate host groups revealed huge viral diversity, transforming the understanding of the evolution of vertebrate-associated RNA virus groups. However, the diversity of the DNA and retro-transcribing viruses in these host groups was left uncharacterized. Given that RNA sequencing is capable of revealing viruses undergoing active transcription and replication, we collected previously generated datasets associated with lower vertebrate hosts, and searched them for DNA and retro-transcribing viruses. Our results revealed the complete genome, or “core gene sets”, of 18 vertebrate-associated DNA and retro-transcribing viruses in cartilaginous fishes, ray- finned fishes, and amphibians, many of which had high abundance levels, and some of which showed systemic infections in multiple organs, suggesting active transcription or acute infection within the host. Furthermore, these new findings recharacterized the evolutionary history in the families Hepadnaviridae, Papillomaviridae, and Alloherpesviridae, confirming long-term virus–host codivergence relationships for these virus groups.