National Awakening in Belarus: Elite Ideology to 'Nation' Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Case Study

National Park Service National Park Service U. S. Department of the Interior Civic Engagement www.nps.gov/civic/ Civic Engagement and the Gulag Museum at Perm-36, Russia Through communication with former prisoners and guards and an international dialogue with other "sites of conscience," The Gulag Museum at Perm-36, Russia, is building all its programs on a foundation of civic engagement. In December 1999, National Park Service (NPS) Northeast Regional Director Marie Rust became a founding member of the International Coalition of Historic Site Museums of Conscience. At the Coalition’s first formal meeting, Ms. Rust met Dr. Victor Shmyrov, Director of the Gulag Museum at Perm-36 in Russia, another founding institution of the Coalition. Dr. Shmyrov’s museum preserves and interprets a gulag camp built under Joseph Stalin in 1946 near the city of Perm in the village of Kutschino, Russia. Known as Perm-36, the camp served initially as a regular timber production labor camp. Later, the camp became a particularly isolated and severe facility for high government officials. In 1972, Perm-36 became the primary facility in the country for persons charged with political crimes. Many of the Soviet Union’s most prominent dissidents, including Vladimir Bukovsky, Sergei Kovalev and Anatoly Marchenko, served their sentences there. It was only during the Soviet government’s period of “openness” of Glasnost, under President Mikael Gorbachev, that the camp was finally closed in 1987. Although there were over 12,000 forced labor camps in the former Soviet Union, Perm-36 is the last surviving example from the system. -

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

28. Rights Defense and New Citizen's Movement

JOBNAME: EE10 Biddulph PAGE: 1 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Fri May 10 14:09:18 2019 28. Rights defense and new citizen’s movement Teng Biao 28.1 THE RISE OF THE RIGHTS DEFENSE MOVEMENT The ‘Rights Defense Movement’ (weiquan yundong) emerged in the early 2000s as a new focus of the Chinese democracy movement, succeeding the Xidan Democracy Wall movement of the late 1970s and the Tiananmen Democracy movement of 1989. It is a social movement ‘involving all social strata throughout the country and covering every aspect of human rights’ (Feng Chongyi 2009, p. 151), one in which Chinese citizens assert their constitutional and legal rights through lawful means and within the legal framework of the country. As Benney (2013, p. 12) notes, the term ‘weiquan’is used by different people to refer to different things in different contexts. Although Chinese rights defense lawyers have played a key role in defining and providing leadership to this emerging weiquan movement (Carnes 2006; Pils 2016), numerous non-lawyer activists and organizations are also involved in it. The discourse and activities of ‘rights defense’ (weiquan) originated in the 1990s, when some citizens began using the law to defend consumer rights. The 1990s also saw the early development of rural anti-tax movements, labor rights campaigns, women’s rights campaigns and an environmental movement. However, in a narrow sense as well as from a historical perspective, the term weiquan movement only refers to the rights campaigns that emerged after the Sun Zhigang incident in 2003 (Zhu Han 2016, pp. 55, 60). The Sun Zhigang incident not only marks the beginning of the rights defense movement; it also can be seen as one of its few successes. -

Science Lessons from the Gulag

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS 1930s. During the Great Terror of 1936–38 alone, some 1.5 million people were arrested and about 700,000 shot in a paroxysm of state-directed violence. In the journey to Wangenheim’s own end, the letters he sent from prison to his daughter Eleonora — just short of four years old at the time of his arrest — offer a counterpoint of hope. It was MEMORIAL/EDITIONS PAULSEN these that inspired the book. Rolin came upon Eleonora’s compila- tion of the letters in 2012, while visiting Russia. There are dozens of beautiful still- life sketches made by the meteorologist in prison — of clouds, aurorae, animals, fruit, aeroplanes, boats, leaves, trees. The colour drawings, some reproduced in the book, were partly a chronicle of life in the Gulag, but also a pedagogical tool. As Rolin notes, Wangenheim “was using plants to teach his daughter the basics of arithmetic and geometry” through riddles outlined in Alexey Wangenheim’s letters home included drawings and riddles about science and nature. accompanying text. In one, the “lobes of a leaf represented the elementary numbers, HISTORY its shape symmetry and asymmetry, while a pine cone illustrated the spiral”. The Solovki prison camp, in which Wangenheim crafted these lessons, was housed in a former Russian Orthodox mon- Science lessons astery on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea. Although his time there was unimagi- nably harsh — with forced labour, poor food and grossly inadequate health care — the from the Gulag prison was unusual in having a well-stocked library and access to a radio, art supplies and Asif Siddiqi examines a biography of a Soviet stationery. -

Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past: a Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region

CBEES State of the Region Report 2020 Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region Published with support from the Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies (Östersjstiftelsen) Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region December 2020 Publisher Centre for Baltic and East European Studies, CBEES, Sdertrn University © CBEES, Sdertrn University and the authors Editor Ninna Mrner Editorial Board Joakim Ekman, Florence Frhlig, David Gaunt, Tora Lane, Per Anders Rudling, Irina Sandomirskaja Layout Lena Fredriksson, Serpentin Media Proofreading Bridget Schaefer, Semantix Print Elanders Sverige AB ISBN 978-91-85139-12-5 4 Contents 7 Preface. A New Annual CBEES Publication, Ulla Manns and Joakim Ekman 9 Introduction. Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past, David Gaunt and Tora Lane 15 Background. Eastern and Central Europe as a Region of Memory. Some Common Traits, Barbara Trnquist-Plewa ESSAYS 23 Victimhood and Building Identities on Past Suffering, Florence Frhlig 29 Image, Afterimage, Counter-Image: Communist Visuality without Communism, Irina Sandomirskaja 37 The Toxic Memory Politics in the Post-Soviet Caucasus, Thomas de Waal 45 The Flag Revolution. Understanding the Political Symbols of Belarus, Andrej Kotljarchuk 55 Institutes of Trauma Re-production in a Borderland: Poland, Ukraine, and Lithuania, Per Anders Rudling COUNTRY BY COUNTRY 69 Germany. The Multi-Level Governance of Memory as a Policy Field, Jenny Wstenberg 80 Lithuania. Fractured and Contested Memory Regimes, Violeta Davoliūtė 87 Belarus. The Politics of Memory in Belarus: Narratives and Institutions, Aliaksei Lastouski 94 Ukraine. Memory Nodes Loaded with Potential to Mobilize People, Yuliya Yurchuk 106 Czech Republic. -

Curriculum Vitae Javad Morshedloo History Department Tarbiat Modares University (TMU) of Tehran +9821-88823610, [email protected]

Curriculum Vitae Javad Morshedloo History Department Tarbiat Modares University (TMU) of Tehran +9821-88823610, [email protected] Degrees: B.A in History (Ferdowsi University of Mashhad) M.A. in World History (Shahid Beheshti University of Tehran) M.A. Theses: "Christian Missionaries in Qajar Iran and the Iranian Response" PhD in History of Post-Islamic Iran (Tehran University) PhD Thesis: "The Political Structure of Eastern Caucasian Khanates: Developments under Russification: 1750-1850" Fields of Research: Eurasian History, Economic History of Qajar Iran, Socio-Economic History of Modern Muslim World, Intellectual History of Modern Muslim World. Languages: Fluency in Persian & English, Working Competency in Arabic, French, Russian and Turkish. Academic Posts: Assistant Professor of History, Tarbiat Modares University (TMU), Tehran (2017- present) Lecturer: History of Caucasus and Central Asia, University of Tehran (2013-present) Lecturer: World History, University of Tehran (2013-2017) Lecturer: World History, Shahid Beheshti University of Tehran (2013-2016) Lecturer: History of Iran, Khwarazmi University of Tehran (2012-2016) Lecturer: World History, Arak University of Tehran (2010-2012) Memberships: The Association for the Study of Persianate Societies (ASPS) (2015-present) The Iranian Society of History (ISH) (2013-present) 1 Publications: Book: Charchobi bara-ye Pazhuhesh dar Tarikh-e Esalm, [A Persian translation of Islamic History: A Framework for Inquiry, by R. Stephen Humphreys], Tehran: Pazhuheshkade-ye Tarikh-e -

Muslim Life in Central Asia, 1943-1985

Muslim Life in Central Asia, 1943-1985 Eren Murat Tasar, Harvard University, Visiting Research Fellow, Social Research Center, American University of Central Asia The period from World War II to the rise of Gorbachev saw important changes in the realms of Islamic practice, education, and social and moral norms in Soviet Central Asia. In particular, the establishment of four geographic “spiritual administrations” to oversee and manage Muslim religious life in the Soviet Union in 1943 1, the foundation of a special state committee to oversee the affairs of non-Orthodox faiths in 1944, and the opening of the country’s only legal madrasah in 1945 (in Bukhara, Uzbekistan) inaugurated a new chapter in the history of Islam in the Soviet Union. Subsequent decades saw the professionalization of a legally registered, ecclesiastical Islamic hierarchy affiliated with the party-state, as well as the growth of unregistered networks of Islamic teachers and prayer leaders. On a broader societal level, the increased prosperity of the Khrushchev and Brezhnev years (1953-1982) witnessed important social developments such as a sharp decrease in public observance of Islamic rituals and strictures (the prohibition of pork and alcohol consumption, for instance) and, in urban areas, a rise in interfaith marriage. Muslim identity, as well as the social and religious life of Muslim communities, evolved in Central Asia during the Soviet period. Anthropologists, historians, and political scientists studying Islam in Central Asia have debated the nature of this evolution in the realms of social, cultural and political life. The analysis has tended to define the relationship between Muslims and the Soviet 1 These being the spiritual administrations of Russia and Siberia, Transcaucasia, the Northern Caucasus, and Central Asia and Kazakstan (SADUM). -

The Impact of China's Rise on Eu Foreign Policy Cohesion

THE IMPACT OF CHINA’S RISE ON EU FOREIGN POLICY COHESION By Dominik Hertlik Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations Supervisor: Dr. Daniel Izsak CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary Word count: 14.299 2020 Abstract China’s rise and the consequences resulting from it have an effect on countries around the world. Its increasingly close cooperation with countries in Central and Eastern Europe (as well as Greece) has led to numerous EU member states (EUMS) pursuing foreign policies that are oftentimes more aligned with the interests of the Chinese leadership than the overall EU’s interests and values. The Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) of the EU is susceptible to such interference as its decisions are based on unanimity. Building up on this, this thesis argues that even though previous literature suggests that normative socialisation processes within CFSP policymaking and the consequent primacy of consensus seeking during negotiations have made the use of vetoes virtually insignificant, due to the increasing political and economic influence of China on some EUMS the importance of vetoes is rising again. Benefits of maintaining amicable relations to China might appear so attractive to some EUMS that in the light of China’s rise they are once again more prone to vetoing certain EU-level decisions critical of Beijing. The benefits held out in prospect vary and can be mostly economic, but also of political or ideological use. Costs of vetoing (besides from the reputational loss) seem to be virtually non-existent. -

Corruption Perceptions Index 2020

CORRUPTION PERCEPTIONS INDEX 2020 Transparency International is a global movement with one vision: a world in which government, business, civil society and the daily lives of people are free of corruption. With more than 100 chapters worldwide and an international secretariat in Berlin, we are leading the fight against corruption to turn this vision into reality. #cpi2020 www.transparency.org/cpi Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of January 2021. Nevertheless, Transparency International cannot accept responsibility for the consequences of its use for other purposes or in other contexts. ISBN: 978-3-96076-157-0 2021 Transparency International. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under CC BY-ND 4.0 DE. Quotation permitted. Please contact Transparency International – [email protected] – regarding derivatives requests. CORRUPTION PERCEPTIONS INDEX 2020 2-3 12-13 20-21 Map and results Americas Sub-Saharan Africa Peru Malawi 4-5 Honduras Zambia Executive summary Recommendations 14-15 22-23 Asia Pacific Western Europe and TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE European Union 6-7 Vanuatu Myanmar Malta Global highlights Poland 8-10 16-17 Eastern Europe & 24 COVID-19 and Central Asia Methodology corruption Serbia Health expenditure Belarus Democratic backsliding 25 Endnotes 11 18-19 Middle East & North Regional highlights Africa Lebanon Morocco TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL 180 COUNTRIES. 180 SCORES. HOW DOES YOUR COUNTRY MEASURE UP? -

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

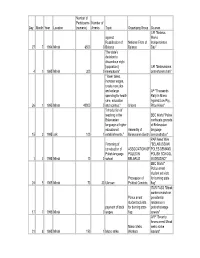

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Evolution of the Belarusian National Movement in The

EVOLUTION OF THE BELARUSIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT IN THE PAGES OF PERIODICALS (1914-1917) By Aliaksandr Bystryk Submitted to Central European University Nationalism Studies Program In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Advisor: Professor Maria Kovacs Secondary advisor: Professor Alexei Miller CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2013 Abstract Belarusian national movement is usually characterised by its relative weakness delayed emergence and development. Being the weakest movement in the region, before the WWI, the activists of this movement mostly engaged in cultural and educational activities. However at the end of First World War Belarusian national elite actively engaged in political struggles happening in the territories of Western frontier of the Russian empire. Thus the aim of the thesis is to explain how the events and processes caused by WWI influenced the national movement. In order to accomplish this goal this thesis provides discourse and content analysis of three editions published by the Belarusian national activists: Nasha Niva (Our Field), Biełarus (The Belarusian) and Homan (The Clamour). The main findings of this paper suggest that the anticipation of dramatic social and political changes brought by the war urged national elite to foster national mobilisation through development of various organisations and structures directed to improve social cohesion within Belarusian population. Another important effect of the war was that a part of Belarusian national elite formulated certain ideas and narratives influenced by conditions of Ober-Ost which later became an integral part of Belarusian national ideology. CEU eTD Collection i Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1. Between krajowość and West-Russianism: The Development of the Belarusian National Movement Prior to WWI ..................................................................................................... -

The State of Human Rights and Political Freedoms in Belarus: Was the Crisis Inevitable?

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47669/PSPRP-4-2020 The State of Human Rights and Political Freedoms in Belarus: Was the Crisis Inevitable? Nina Kolarzik and Aram Terzyan Center for East European and Russian Studies Post-Soviet Politics Research Papers 4/2020 Nina Kolarzik and Aram Terzyan Abstract The rule of Alexander Lukashenko in Belarus has created one of the most resilient authoritarian regimes in post-communist Europe. Meanwhile, the turmoil triggered by the 2020 presidential election has put in the spotlight the mounting challenges facing Lukashenko’s authoritarian rule. This paper investigates the state of human rights and political freedoms in Belarus, focusing on the main rationale behind the turmoil surrounding the 2020 presidential election. It concludes that the political crisis following the elections is the unsurprising consequence of Lukashenko’s diminishing ability to maintain power or concentrate political control by preserving elite unity, controlling elections, and/or using force against opponents. Keywords: Belarus, human rights, authoritarian rule, elections, civil society. Introduction Situated in the European Union - Russia shared neighborhood, Belarus has been characterized by ‘Soviet nostalgia’ rather than European aspirations. Politically, Belarus shows more similarities with the republics of post-Soviet Central Asia than with its neighbors in Europe. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union Belarus has gone from being a new and fragile democracy to a pariah state, largely regarded as “the last dictatorship in Europe” (Rudling 2008). Nevertheless, the anti-government protests following the 2020 presidential election show that despite the administrative, police and propaganda measures the Belarusian opposition and civil society managed to produce a real challenge to the existing status quo.