Int Cat Css Blr 30785 E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Structural Geological Mapping of the Cenozoic Sediments of the Brest Region Using GIS Technologies

E3S Web of Conferences 212, 01010 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202021201010 ICBTE 2020 Structural geological mapping of the Cenozoic sediments of the Brest region using GIS technologies Anna Maevskaya1*, Nikolay Sheshko2, Natalia Shpendik2 and Maksim Bogdasarov1 1Brest State University named after A.S. Pushkin Cosmonauts Boulevard, 21, 224016, Brest, Belarus 2Brest State Technical University Moskovskaya St., 267, 224017, Brest, Belarus Abstract. Cenozoic sediments of the territory of the Brest region is the object of research in this work. The aim of this work is to detail the structure of the Cenozoic stratigraphic deposits by creating a set of structural geological maps. The process of creating maps included several sequential stages implemented using the ArcGIS 10.5 software product. In general, a set of maps for each period of the Cenozoic era was made according to the implemented method. As a result of mapping, the features of the geological structure of the Cenozoic sediments were detailed (based on the use of the most complete materials on the drilling exploration of the territory during the construction). The use of geoinformation systems in the process of building will allow for quick updating of cartographic materials in the future. Keywords: Brest region, cenozoic sediment, gis mapping, big data, structural-geological maps. Introduction Cenozoic deposits have become quite widespread within the territory of the Brest region, which due to their lithological diversity can be considered as a promising regional resource base of minerals, primarily building materials. This necessitates a serious detailing of the nature of the surface of the buried horizons of the Cenozoic as a basis for a qualitative forecast and assessment of the prospects for the development of the mineral resource potential of the territory as well as optimization of the organization of engineering and construction activities. -

Global Human Rights

FINANCIAL REPORTING AUTHORITY (CAYFIN) Delivery Address: th Mailing Address: 133 Elgin Ave, 4 Floor P.O. Box 1054 Government Administrative Building Grand Cayman KY1-1102 Grand Cayman CAYMAN ISLANDS CAYMAN ISLANDS Direct Tel No. (345) 244-2394 Tel No. (345) 945-6267 Fax No. (345) 945-6268 Email: [email protected] Financial Sanctions Notice 29/09/2020 Global Human Rights Introduction 1. The Global Human Rights Sanctions Regulations 2020 (S.I. 680/2020) (the Regulations) were made under the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 (the Sanctions Act) and provide for the freezing of funds and economic resources of certain persons, entities or bodies responsible for or involved in serious violations of human rights. 2. The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office have updated the UK Sanctions List on GOV.UK. This list includes details of all sanctions enacted under the Sanctions Act. A link to the UK Sanctions List can be found below. 3. Following the publication of the UK Sanctions List, information on the Consolidated List has been updated. Notice summary 4. 8 entries listed in the annex to this Notice have been added to the Consolidated List and are now subject to an asset freeze. 5. The identifying information for one individual has been updated and he remains subject to an asset freeze. What you must do 6. You must: i. check whether you maintain any accounts or hold any funds or economic resources for the persons set out in the Annex to this Notice; ii. freeze such accounts, and other funds or economic resources and any funds which are owned or controlled by persons set out in the Annex to the Notice; iii. -

L319 I Official Journal

Official Journal L 319 I of the European Union Volume 63 English edition Legislation 2 October 2020 Contents II Non-legislative acts REGULATIONS ★ Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/1387 of 2 October 2020 implementing Article 8a(1) of Regulation (EC) No 765/2006 concerning restrictive measures in respect of Belarus . 1 DECISIONS ★ Council Implementing Decision (CFSP) 2020/1388 of 2 October 2020 implementing Decision 2012/642/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against Belarus . 13 Acts whose titles are printed in light type are those relating to day-to-day management of agricultural matters, and are generally valid for a limited period. EN The titles of all other acts are printed in bold type and preceded by an asterisk. 2.10.2020 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 319 I/1 II (Non-legislative acts) REGULATIONS COUNCIL IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2020/1387 of 2 October 2020 implementing Article 8a(1) of Regulation (EC) No 765/2006 concerning restrictive measures in respect of Belarus THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 765/2006 of 18 May 2006 concerning restrictive measures in respect of Belarus (1), and in particular Article 8a(1) thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Whereas: (1) On 18 May 2006, the Council adopted Regulation (EC) No 765/2006 concerning restrictive measures in respect of Belarus. (2) On 9 August 2020, Belarus conducted presidential elections, which were found to be inconsistent with international standards and marred by repression of independent candidates and a brutal crackdown on peaceful protesters in the wake of the elections. -

2. Historical, Cultural and Ethnic Roots1

2. HISTORICAL, CULTURAL AND ETHNIC ROOTS1 General features of ethnic identity evolution history, to develop autonomous state structures, in the eastern part of Europe their lives have mostly been determined by out- side forces with diverse geopolitical interests. Differences may be observed between Eastern The uncertain political situation of past cen- and Western Europe in terms of the ethnogenesis turies gave rise – along the linguistic, cultural of the peoples and the development of their eth- and political fault lines – to several ethnic groups nic identity. In the eastern half of the continent, with uncertain identities, disputed allegiances rather than be tied to the confines of a particular and divergent political interests. Even now, there state, community identity and belonging have exist among the various groups overlaps, differ- tended to emerge from the collective memory of ences and conflicts which arose in earlier periods. a community of linguistic and cultural elements The characteristic features of the groups have not or, on occasion, from the collective memory of a been placed in a clearly definable framework. state that existed in an earlier period (Romsics, In the eastern half of Europe, the various I. 1998). The evolution of the eastern Slavic and ethnic groups are at different stages of devel- Baltic peoples constitutes a particular aspect of opment in terms of their ethnic identity. The this course. We can, therefore, gain insights into Belarusian people, who speak an eastern Slavic the historical foundations of the ethnic identity language, occupy a special place among these of the inhabitants of today’s Belarus – an identity groups. -

Billing Code 4810-Al Department

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 12/30/2020 and available online at example.com/d/2020-28863, and on govinfo.govBILLING CODE 4810-AL DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Office of Foreign Assets Control Notice of OFAC Sanctions Actions AGENCY: Office of Foreign Assets Control, Treasury. ACTION: Notice. SUMMARY: The Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is publishing the names of one or more persons that have been placed on OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List based on OFAC’s determination that one or more applicable legal criteria were satisfied. All property and interests in property subject to U.S. jurisdiction of these persons are blocked, and U.S. persons are generally prohibited from engaging in transactions with them. DATES: See SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION section for effective date(s). FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: OFAC: Andrea Gacki, Director, tel.: 202-622-2420; Associate Director for Global Targeting, tel.: 202-622-2420; Assistant Director for Sanctions Compliance & Evaluation, tel.: 202-622-2490; Assistant Director for Licensing, tel.: 202-622-2480; or Assistant Director for Regulatory Affairs, tel.: 202- 622-4855. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Electronic Availability The Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List and additional information concerning OFAC sanctions programs are available on OFAC’s website (https://www.treasury.gov/ofac). Notice of OFAC Action(s) On December 23, 2020, OFAC determined that the property and interests in property subject to U.S. jurisdiction of the following persons are blocked under the relevant sanctions authority listed below. Individual: 1. KAZAKEVICH, Henadz Arkadzievich (Cyrillic: КАЗАКЕВIЧ, Генадзь Аркадзьевiч) (a.k.a. -

Prospects for Democracy in Belarus

An Eastern Slavic Brotherhood: The Determinative Factors Affecting Democratic Development in Ukraine and Belarus Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nicholas Hendon Starvaggi, B.A. Graduate Program in Slavic and East European Studies The Ohio State University 2009 Thesis Committee: Trevor Brown, Advisor Goldie Shabad Copyright by Nicholas Hendon Starvaggi 2009 Abstract Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, fifteen successor states emerged as independent nations that began transitions toward democratic governance and a market economy. These efforts have met with various levels of success. Three of these countries have since experienced “color revolutions,” which have been characterized by initial public demonstrations against the old order and a subsequent revision of the rules of the political game. In 2004-2005, these “color revolutions” were greeted by many international observers with optimism for these countries‟ progress toward democracy. In hindsight, however, the term itself needs to be assessed for its accuracy, as the political developments that followed seemed to regress away from democratic goals. In one of these countries, Ukraine, the Orange Revolution has brought about renewed hope in democracy, yet important obstacles remain. Belarus, Ukraine‟s northern neighbor, shares many structural similarities yet has not experienced a “color revolution.” Anti- governmental demonstrations in Minsk in 2006 were met with brutal force that spoiled the opposition‟s hopes of reenacting a similar political outcome to that which Ukraine‟s Orange Coalition was able to achieve in 2004. Through a comparative analysis of these two countries, it is found that the significant factors that prevented a “color revolution” in Belarus are a cohesive national identity that aligns with an authoritarian value system, a lack of engagement with U.S. -

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern Eine Beschäftigung I

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern eine Beschäftigung i. S. d. ZRBG schon vor dem angegebenen Eröffnungszeitpunkt glaubhaft gemacht ist, kann für die folgenden Gebiete auf den Beginn der Ghettoisierung nach Verordnungslage abgestellt werden: - Generalgouvernement (ohne Galizien): 01.01.1940 - Galizien: 06.09.1941 - Bialystok: 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ostland (Weißrussland/Weißruthenien): 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ukraine (Wolhynien/Shitomir): 05.09.1941 Eine Vorlage an die Untergruppe ZRBG ist in diesen Fällen nicht erforderlich. Datum der Nr. Ort: Gebiet: Eröffnung: Liquidierung: Deportationen: Bemerkungen: Quelle: Ergänzung Abaujszanto, 5613 Ungarn, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, Braham: Abaújszántó [Hun] 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Kassa, Auschwitz 27.04.2010 (5010) Operationszone I Enciklopédiája (Szántó) Reichskommissariat Aboltsy [Bel] Ostland (1941-1944), (Oboltsy [Rus], 5614 Generalbezirk 14.08.1941 04.06.1942 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, 2001 24.03.2009 Oboltzi [Yid], Weißruthenien, heute Obolce [Pol]) Gebiet Vitebsk Abony [Hun] (Abon, Ungarn, 5443 Nagyabony, 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 2001 11.11.2009 Operationszone IV Szolnokabony) Ungarn, Szeged, 3500 Ada 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Braham: Enciklopédiája 09.11.2009 Operationszone IV Auschwitz Generalgouvernement, 3501 Adamow Distrikt Lublin (1939- 01.01.1940 20.12.1942 Kossoy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 09.11.2009 1944) Reichskommissariat Aizpute 3502 Ostland (1941-1944), 02.08.1941 27.10.1941 USHMM 02.2008 09.11.2009 (Hosenpoth) Generalbezirk -

Final Report. Electoral Campaign-2019 Download

www.pvby.org RIGHT TO CHOOSE-2019 CAMPAIGN on the observation of the election of deputies to the House of Representatives of the National Assembly of the Republic of Belarus of the 7th Convocation _____________________________________________________________________________ Final report November 21, 2019 KEY CONCLUSIONS 1. No amendments have been introduced into Electoral Code and law enforcement practice since the end of previous election campaign. 2. Same as before, the absence of guarantees enshrined in electoral law for representation of political parties-electoral subjects at the level of election commissions allows for using arbitrary and discriminatory approach towards opposition parties and movements in the process of formation of election commissions. 3. A significant number of members of district commissions (22 persons) and precinct commissions (950 persons) represent political parties that are not involved in the election process. 4. The process of filing appeals against refusals to register MP candidates is a mere formality, since there are no clear criteria for the formation of election commissions. 5. The election campaign is conducted under conditions of constant pressure against opposition candidates. Any and all political slogans are regarded as a violation of Article 47 of the Electoral Code of the Republic of Belarus (ECRB). State authorities resort to ongoing censorship of more or less sharp speeches published in the media by interpreting Articles 47 and 75 of the ECRB in an arbitrary way. 6. Opposition candidates -

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

QA Refunds Over $1.2Bn to Customers Since March

www.thepeninsula.qa Wednesday 19 August 2020 Volume 25 | Number 8354 29 Dhul-Hijja - 1441 2 Riyals BUSINESS | 13 PENMAG | 15 SPORT | 20 Only ‘good’ debt Classifieds Diamond League can save and Services to resume Europe’s section Qatar’s sports economy: Draghi included season Choose the network of heroes Enjoy the Internet QA refunds over $1.2bn to customers since March THE PENINSULA — DOHA passengers. Qatar Airways automation capabilities, with tickets are now valid for two customers being able to request Qatar Airways has paid out over years from the date of issuance. their refund online, from which $1.2bn in refunds to almost Passengers can also choose point it can largely be processed 600,000 passengers since to change their travel date or des- automatically. The airline also March, demonstrating its tination free of charge as often as automated travel voucher commitment to honouring its they need, change their origin to requests, so that passengers were obligations to passengers who another city within the same able to receive a voucher within need to change their plans due country or any other destination 72 hours of requesting it online. to the impact of the COVID-19 on the airline’s network within a In terms of manpower, Qatar pandemic on global travel. 5,000 mile radius of the original, Airways redeployed employees In the context of unprece- exchange their ticket for a future from other areas of the business dented numbers of refund travel voucher worth 110 percent – for example its Cabin Crew requests as airlines and pas- of the original ticket value, or and Ground Services staff – to sengers navigate entry restrictions swap their tickets for Qmiles. -

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

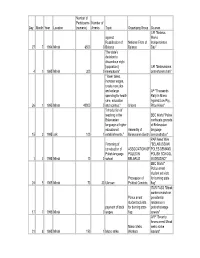

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Qatar Airways Keeps Its Word

INDEX QATAR 2-4,16 COMMENT 14, 15 BUSINESS | Page 1 QATAR | Page 4 ARAB WORLD 6 BUSINESS 1-8 QP enters INTERNATIONAL 6-13 SPORTS 1-8 Qeeri at the exploration DOW JONES QE NYMEX forefront of agreement in Qatar’s solar 27,778.07 9,775.28 42.89 Angola -66.84 +79.96 +0.00 vision -0.24% +0.82% +0.00% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 WEDNESDAY Vol. XXXXI No. 11645 August 19, 2020 Dhul-Hijjah 29, 1441 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Qatar ratifies MP14 to address issue of PSG reach first-ever Champions League final unruly passengers Qatar has become the latest Qatar Airways country to ratify the Montreal Protocol of 2014 (MP14), making it the 23rd country globally and sixth in Africa & the Middle East region to give formal approval to keeps its word; the treaty, the International Air Transport Association has said. MP14, properly named the Protocol to Amend the Convention on Off ences and Certain Other Acts refunds $1.2bn Committed on Board Aircraft, is a global agreement that strengthens the powers of States to prosecute unruly passengers. Page 4 ‘Palestinians not worried to passengers about Israel-UAE deal’ atar Airways has paid out in original, exchange their ticket for a Palestinian President Mahmoud excess of $1.2bn in refunds to future travel voucher worth 110% of Abbas said yesterday that Qalmost 600,000 passengers the original ticket value, or swap their Palestinians were not concerned since March, demonstrating its com- tickets for Qmiles. about the normalisation deal mitment to honouring its obligations Over one third (36%) of Qatar Air- between Israel and the United Arab to passengers who need to change their ways passengers selected one of these Emirates, referring to the accord plans due to the impact of the Cov- options over a refund, the airline said.