Gaur As 'Monument': the Making of an Archive and Tropes of Memorializing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit-1 T. S. Eliot : Religious Poems

UNIT-1 T. S. ELIOT : RELIGIOUS POEMS Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 ‘A Song for Simeon’ 1.3 ‘Marina’ 1.4 Let us sum up 1.5 Review Questions 1.6 A Select Bibliography 1.0 Objectives The present unit aims at acquainting you with some of T.S. Eliot’s poems written after his confirmation into the Anglo-Catholic Church of England in 1927. With this end in view, this unit takes up a close reading of two of his ‘Ariel Poems’ and focuses on some traits of his religious poetry. 1.1 Introduction Thomas Stearns Eliot was born on 26th September, 1888 at St. Louis, Missouri, an industrial city in the center of the U.S.A. He was the seventh and youngest child of Henry Ware Eliot and Charlotte Champe Stearns. He enjoyed a long life span of more than seventy-five years. His period of active literary production extended over a period of forty-five years. Eliot’s Calvinist (Puritan Christian) ancestors on father’s side had migrated in 1667 from East Coker in Somersetshire, England to settle in a colony of New England on the eastern coast of North America. His grandfather, W.G. Eliot, moved in 1834 from Boston to St. Louis where he established the first Unitarian Church. His deep academic interest led him to found Washington University there. He left behind him a number of religious writings. Eliot’s mother was an enthusiastic social worker as well as a writer of caliber. His family background shaped his poetic sensibility and contributed a lot to his development as a writer, especially as a religious poet. -

Reconsidering Local History: Some Facts, Some Observations

CHAPTER 31 Reconsidering Local History: Some Facts, Some Observations JAWHAR SIRCAR A Plea for Local History The bureaucratization of history in the twentieth century has led to its transformation into a more professional academic discipline, but a growing distinction thus developed between professionals and amateurs. The former, sacerdotal in outlook and superior in attitude, regarded the latter with disdain. They, in turn, felt resentment towards professionals who increasingly dominated a field of study the amateurs had once ruled. In the end, the bureaucratization of learning inevitably meant the exclusion of those who did not possess proper academic credentials.1 this was the candid opening sentence of a well-known American historian, but the tenor in which he continued was equally incisive and applies to academics per se, without pinpointing on History alone. ‘The bureaucratization of learning’, he said, ‘led in turn to growing estrangement between the broad educated public and the world of scholarship’, and scholars who tried to ‘bridge the widening gap between abstract thought and everyday existence’ were dismissed as journalists, popularizers, or hacks. Though quite unexpected from a formal historian, this was part of Theodore S. Hamerow’s address at the annual conference of the American Historical Association of 1988, held at Cincinnati. What the immediate provocation was for Hamerow to deliberately heat up the atmosphere in the post-Christmas chill is not known, but let us first hear him out. According to him, ‘historical research had been conducted for over two thousand years, not by professional scholars but by self-taught amateurs who had spent most of their lives in politics, warfare, theology, bureaucracy, 836 Jawhar Sircar journalism, or literature longer than in any other field of learning’. -

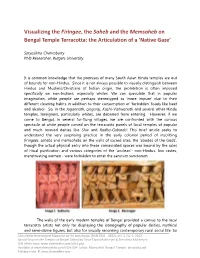

Visualizing the Firingee, the Saheb and the Memsaheb on Bengal Temple Terracotta: the Articulation of a ‘Native Gaze’

Visualizing the Firingee, the Saheb and the Memsaheb on Bengal Temple Terracotta: the Articulation of a ‘Native Gaze’ Satyasikha Chakraborty PhD Researcher, Rutgers University It is common knowledge that the premises of many South Asian Hindu temples are out of bounds for non-Hindus. Since it is not always possible to visually distinguish between Hindus and Muslims/Christians of Indian origin, the prohibition is often imposed specifically on non-Indians, especially whites. We can speculate that in popular imagination, white people are perhaps stereotyped as ‘more impure’ due to their different cleaning habits in addition to their consumption of ‘forbidden’ foods like beef and alcohol. So, in the Jagannath, Lingaraj, Kashi-Vishwanath and several other Hindu temples, foreigners, particularly whites, are debarred from entering. However, if we come to Bengal, in several far-flung villages, we are confronted with the curious spectacle of white people carved on the terracotta panels of local temples of popular and much revered deities like Shiv and Radha-Gobindo! This brief article seeks to understand the very surprising practice in the early colonial period of inscribing firingees, sahebs and memsahebs on the walls of sacred sites, the ‘abodes of the Gods’, though the actual physical entry into these consecrated spaces was bound by the rules of ritual purification and various categories of the ‘unclean’- non-Hindus, low castes, menstruating women - were forbidden to enter the sanctum sanctorum. The walls of the early modern temples of Bengal provided a canvas to the local terracotta artists not only for displaying the iconography of popular deities, mythical and semi-divine figures, but also for visually recording contemporary rural social life. -

2015 Williams Richard 113649

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Hindustani music between Awadh and Bengal, c.1758-1905 Williams, Richard David Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 Hindustani music between Awadh and Bengal, c.1758-1905 RICHARD DAVID WILLIAMS Submitted in FulFilment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor oF Philosophy KING’S COLLEGE LONDON DECEMBER 2014 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the interaction between Hindustani and Bengali musicians and their patrons over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the convergence of Braj, Persianate, and Bengali musical cultures in Bengal after 1856. -

2005 Annual Report.Pdf

jesus college • cambridge one hundred and first annual report 2005 jesus college • cambridge one hundred and first annual report 2005 photo: frances willmoth Above, two men paddling in a boat; below, Jonah emerges from the fish’s mouth and clutches a tree From July to December this year the Fitzwilliam Museum is showing a most magnificent exhibition of illuminated manuscripts, many of which are from college collections. Jesus was not asked to lend anything for this exhibition – ‘as most of our manuscripts are of the working kind and not elaborately decorated’. Some of the college manuscripts, however, do have illuminations. A 13th century Holy Bible in the college’s collection (Q.A.11: no. 11 in M. R. James’ 1895 catalogue) not only has beautiful writing but ‘historiated initials of more than usual interest’. So that readers can see something of what the Fitzwilliam has missed, this year’s Annual Report carries a number of illustrations taken from that Bible. COPYRIGHT This publication is protected by international copyright law. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems – without the prior permission of the copyright holders, except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. contents Message from the Master 5 The College Year 2004–5 7 College News 7 Domestic Bursar’s Notes 13 The Old Library and College Archives 15 Chapel 17 Chapel Music 19 Art 20 Sculpture in the Close 21 Development Office 24 Development Director’s Report 24 Society of St Radegund 24 Bequests 24 Report of Events 24 Calendar of Events 2005–6 30 M.A. -

Terracotta Temples of Bengal: a Culmination of Pre-Existing Architectural Styles

The Chitrolekha Journal on Art and Design (E-ISSN 2456-978X), Vol. 1, No. 1, 2017 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/cjad.v1n1.v1n105 PDF URL: www.chitrolekha.com/ns/v1n1/v1n105.pdf www.chitrolekha.com © AesthetixMS Terracotta Temples of Bengal: A Culmination of Pre-existing Architectural Styles Sudeshna Guha1 & Dr. Abir Bandyopadhyay2 1B. Arch Student, National Institute of Technology Raipur, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India. Email: [email protected] 2Professor, Department of Architecture, National Institute of Technology Raipur, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Three major developments in religious architecture were seen in three different eras of Bengal’s history – evolution of Nagara style temples which were influenced by the Orissan Rekha deuls, followed by the developments of Islamic Architecture through mosques and tombs, and lastly, the generation of Terracotta Temples. The Terracotta Temples of Bengal, famous for the use of Terracotta Plaques for surface decoration, had developed a unique style of architecture, quite distinct from the major styles of temple architecture that was prevailing in India. This paper intends to find out which architectural features of the Terracotta Temples got influenced and how they got influenced from the prevailing architectural styles. Keywords: Terracotta Temples, influence, architectural features, Islamic architecture, Pre-Islamic architecture. INTRODUCTION 1.1 RELIGIOUS ARCHITECTURE OF BENGAL The region of Bengal consisting of present day West Bengal, Bangladesh, and some Bengali speaking areas of Bihar, Jharkhand, Assam, and Tripura (R.C. Majumdar, 1971) had witnessed development of a drastic divergent style of temple architecture. The initial phases (till 1200 A.D.) showed the development of typical Nagara style temples, while in the ‘Late medieval period’ (McCutchion, 2004) the temples started developing unique and distinct architectural characteristics. -

Terracotta Temples of Bishnupur: Transformation Through Time and Technology Priyanka Mangaonkar

Terracotta Temples of Bishnupur: Transformation through Time and Technology Priyanka Mangaonkar Rashmancho, Bishnupur Introduction Clay can be considered as one of the oldest building materials in the history of man after stone. Clay was and is being used for all conceivable purposes due to its abundance and universal supply. The discovery of baking clay provided the permanence to the clay objects. This baked clay is called as Terracotta. All over the world, across the ages people have transformed this heavy, dark and formless material into a lighter building material. They created their living spaces and they adapted their architectural and constructive answers according to the behavior and properties of the soil. The use of Terracotta as a material evolved from making objects of daily needs like vessels, pottery, toys, seals etc in ancient times to its use in temples in the 15th-16th century AD in West Bengal. Until this period Stone was the main material used for building temples. This was due to unavailability of the stone and availability of good alluvial soil, and the need to create pseudo effect, e.g. in West Bengal terracotta was used to depict stone carvings and sometimes to resemble the articulation on wooden door. In the same period, from 15th to early 20th century terracotta was used as cheaper and easily available option for marble in some parts of Europe. Chitrolekha International Magazine on Art and Design, (ISSN 2231—4822), Vol. 1, No. 2, August, 2011 URL of the Issue: www.chitrolekha.com/v1n2.php Available at www.chitrolekha.com/V1/n2/04_terracotta_Architecture_of_Bankura_technology.pdf Kolkata, India. -

Cbcs:-2020-2021

Resolutions of PGBS meeting (History) held online through Google meet on 25/11/2020 at 10.30 am Members Present Prof. Ujjayan Bhattacharya( VU): External Expert Prof. Kaushik Roy( JU): External Expert Dr Malabika Ray Prof. Achintya Kumar Dutta Prof. Pradip Chattopadhyay Dr Sudit Krishna Kumar Dr Aparajita Dhar Dr Binata Sarkar Dr Rajarshi Chakrabarty Agenda: Restructuring of PG Syllabus(CBCS) Resolutions: The syllabus has been thoroughly discussed. External experts have given their opinions and the syllabus has been approved unanimously. The meeting ended with a vote of thanks to the Chair. Department of History The University of Burdwan Restructuring of PG Syllabus (History) - 2020 Preamble The Department of History has undertaken the initiative to restructure the syllabus at the Post-Graduate level as per the guidelines set by the Syllabus Committee, Arts Faculty, the University of Burdwan. The purpose is to introduce a common pattern of syllabus in all subjects under the UGC prescribed CBCS system and to infuse uniformity in the syllabi across the disciplines. The PG syllabus of History shall have a total of 1020 marks divided into 20 courses of 50 marks each and an additional 20 marks for Community Engagement Course. Keeping in tune with the decision to offer various types of courses there are altogether four types of courses on offer in the department of History. 1. Core Course, 2. Major Elective Course, 3. Inter-disciplinary Elective, and 4. Community Engagement Course. The Project Paper is being bracketed under the category of Core course. Each course of 50 marks shall be of 5 credits each except the Inter-disciplinary Elective course which shall be of 4 credits and the Community Engagement Course with 2 credits. -

Comparative Literature in India: an Overview of Its History

Comparative Literature in India: An Overview of its History Subha Chakraborty Dasgupta, Jadavpur University Abstract: The essay gives an overview of the trajectory of Comparative Literature in India, focusing pri- marily on the department at Jadavpur University, where it began, and to some extent the department of Modern Indian Languages and Literary Studies in the University of Delhi, where it later had a new be- ginning in its engagement with Indian literatures. The department at Jadavpur began with the legacy of Rabindranath Tagore’s speech on World Literature and with a modern poet-translator as its founder. While British legacies in the study of literature were evident in the early years, there were also subtle efforts towards a decolonizing process and an overall attempt to enhance and nurture creativity. Gradually Indian literature began to receive prominence along with literatures from the Southern part of the globe. Paradigms of approaches in comparative literary studies also shifted from influence and analogy studies to cross-cultural literary relations, to the focus on reception and transformation. In the last few years Comparative Literature has taken on new perspectives, engaging with different ar- eas of culture and knowledge, particularly those related to marginalized spaces, along with the focus on recovering new areas of non-hierarchical literary relations. Keywords: decolonizing process, creativity, cross-cultural literary relations, interdisciplinarity The beginnings Long before the establishment of Comparative Literature as a discipline, there were texts focus- ing on comparative aspects of literature in India, both from the point of view of its relation with litera- tures from other parts of the world—particularly Persian, Arabic and English—and from the perspec- tive of inter-Indian literary studies, the multilingual context facilitating a seamless journey from and between literatures written in different languages. -

2010 Winter Newsletter

NEWSLETTER SOUTH ASIAN LITERARY ASSOCIATION An Allied Organization of the MLA WINTER 2010 VOLUME 34, NO. 2 President’s Column 1 UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO El PASO, TX 2011 SALA Conference Program/ 2-5 Acknowledgment of Thanks P RESIDENT’ S COLUMN SALA MLA Sessions/MLA Sessions of Possi- 6 ble Interest President’s Welcome SALA Conference 2011 Conference Abstracts 7-16 Invitation from Gayatri Spivak 17 Welcome to Los Angeles, the home of LA Lakers, and the site of SAR CFP 18 SALA’s first conference of the second decade. I am happy to see those who have returned to meet, and to debate, their old friends, and happier to see Other CFPs 19-21 those who are joining us for the first time. The 2011 Conference co-chairs, “Congratulations to Our Members” Section 22 Raje Kaur and Rashmi Bhatnagar, have put together a vigorous yet prac- tical schedule, and the Secretary Moumin Quazi and Treasurer Robin In Memoria 23-24 Field have done their best to ensure that the logistics of the Conference function smoothly. Now it is our obligation as participants, to see that they New Books of Interest for South Asianists 25-26 do; what is more, it is to our advantage to get the maximum benefit from Life Memberships 26 this meet. Some of you have covered long distances, all of you have sacri- ficed home comforts—and most have done this not, I suppose, just to give SAR and SALA Forms 27 a paper but to chalk for yourself an academic track, to build a lasting SALA Mission Statement 28 friendship, or to lay foundations for a collaborative project. -

Interconnecting Archival and Field Data in Reference to Late Medieval Jor-Bangla Temples of Bengal

Towards an Understanding of Cultural Biography of Monuments: Interconnecting Archival and Field Data in Reference to Late Medieval Jor-Bangla Temples of Bengal By Mrinmoyee Ray Research Scholar Department of History of Art National Museum Institute of History of Art, Conservation and Museology New Delhi India 1 Late medieval period of Bengal history is not only unique in terms of witnessing of the Bhakti movement ushered in by Sri Chatitanya, but also because of the tremendous proliferation in temple building activity in this region which followed. Bengal in this context refers to present day state of West Bengal in India combined with Bangladesh, which was then referred to as the Subah-e- Bangal under the Mughal administration. The reason for such inclusion is to discuss the common stylistic development of temple architecture of this region during the temporal framework dating from 16th century CE to 19th century CE. Even though the early phases of development of temple architecture of this region does show influence of architecture from Orissa, with the Muslim dominion of Bengal there did occur some fundamental shifts in terms of design, material and techniques of construction of these temples. The Islamic rulers introduced their distinctive architectural techniques like dome and arches which were favourably accepted even in the construction of the temples of this region; thereby giving the temples a unique indigenous regional character in terms of the designs mainly inspired by the domestic hut of Bengal. The styles further developed into many sub types like the Chala, Ratna, Jor-Bangla and many more. The process of documenting these temples of this region began as early as 19th century itself by institutions like Archaeological Survey of India and individuals like James Fergusson1 who primarily took measurements, drew illustrations, ground plan and also took photographs. -

Constructing a New Canon of Post-1980S Indian English Fiction

Constructing a New Canon of Post-1980s Indian English Fiction Constructing a New Canon of Post-1980s Indian English Fiction By Sahdev Luhar and Madhurita Choudhary Constructing a New Canon of Post-1980s Indian English Fiction By Sahdev Luhar and Madhurita Choudhary This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Sahdev Luhar and Madhurita Choudhary All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7943-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7943-9 Dedicated to Sahdev’s parents Ratansinh Luhar and Santokben Luhar & Madhurita’s parents Dr Nrityen Saha Choudhury and Madhuri Choudhury The range of the experiences which Indian English (IE) fiction depicts is definitely very narrow and restricted. Much of the best part of our national and cultural life falls outside its purview. It specializes in depicting the experiences of a small section of our middle class; even in this rather limited terrain, its emphasis is on some sort of interaction and intercourse with the West, either through character or through themes. That is why I have argued elsewhere that the IE novel occupies a space similar to that of the Anglo-Indian novel. —Makarand Paranjape A tenaciously particularised religiosity in polyglot jungle of temples and swamis; a more or less official ideal tradition in aesthetics and philosophy but an actual history of eclectic ferment; “non-western” ways of thinking often defined and infused by European romantic idealism.