The New Cambridge History of India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

91 44 2744 2160 Email: [email protected] Web: (Formerly Hi Tours Mamallapuram Pvt Ltd)

Tel: + 91 44 2744 3260 / 2744 3360 / 2744 2460 Fax: 91 44 2744 2160 Email: [email protected] Web: www.travelxs.in (Formerly Hi Tours Mamallapuram Pvt Ltd) TOUR NAME: CENTRAL INDIA TOUR TOUR DAYS: 28 NIGHTS, 29 DAYS ROUTE : DELHI (ARRIVAL) – AGRA – ORCHHA – KHAJURAHO –SANCHI - UJJAIN - MANDU - MAHESHWAR – OMKARESHWAR - AJANTA - AURANGABAD - HYDERABAD – BIJAPUR – BADAMI – HAMPI – CHITRADURGA - SHARAVANBELAGOLA – BANGALORE TOUR LODGING INFO: 27 Nights Hotels, 01 Overnight Trains Accommodation will be provided on room with breakfast basis. For Lunch and dinner there would be an additional supplement. Our aforementioned quoted tour cost is based on Standard Category. Hotel list is as follows:- PLACES COVERED NUMBER OF NIGHTS STANDARD HOTELS DELHI 02 NIGHTS ASTER INN AGRA 02 NIGHTS ROYALE RESIDENCY ORCHHA 02 NIGHT SHEESH MAHAL KHAJURAHO 02 NIGHTS USHA BUNDELA SANCHI 02 NIGHTS GATEWAY RETREAT (MPTDC HOTEL) UJJAIN 02 NIGHTS SHIPRA RESIDENCY (MPTDC HOTEL) MANDU 03 NIGHTS MALWA RESORT (MPTDC HOTEL) MAHESHWAR 01 NIGHT NARMADA RESORT (MPTDC HOTEL) OMKARESHWAR 01 NIGHT NARMADA RESORT (MPTDC HOTEL) AJANTA 01 NIGHT FARDAPUR (MTDC HOTEL) AURANGABAD 01 NIGHT NEW BHARATI OVERNIGHT TRAIN 01 NIGHT HYDERABAD 02 NIGHTS HOTEL GOLKONDA BIJAPUR 01 NIGHT MADHUVAN INTERNATIONAL BADAMI 02 NIGHTS BADAMI COURT HAMPI 01 NIGHT HAMPI BOULDERS CHITRADURGA 01 NIGHT NAVEEN RESIDENCY SHARAVANBELAGOLA 01 NIGHT HOTEL RAGHU TOUR PACKAGE INCLUDES: - Accommodation on twin sharing basis. - Daily Buffet Breakfast. - All transfers / tours and excursions by AC chauffeur driven vehicle. - 2nd AC Sleeper Class Train ticket from Aurangabad - Hyderabad - All currently applicable taxes. TOUR PACKAGE DOES NOT INCLUDE: - Meals at hotels except those listed in above inclusions. - Entrances at all sight seeing spots. -

Unit 9 the Deccan States and the Mugmals

I UNIT 9 THE DECCAN STATES AND THE MUGMALS Structure 9.0 Objectives I 9.1 Iiltroduction 9.2 Akbar and the Deccan States 9.3 Jahangir and the Deccan States 9.4 Shah Jahan and the Deccaa States 9.5 Aurangzeb and the Deccan States 9.6 An Assessnent of the Mughzl Policy in tie Deccan 9.7 Let Us Sum Up 9.8 Key Words t 9.9 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises -- -- 9.0 OBJECTIVES The relations between the Deccan states and the Mughals have been discussed in the present Unit. This Unit would introduce you to: 9 the policy pursued by different Mughal Emperors towards the Deccan states; 9 the factors that determined the Deccan policy of the Mughals, and the ultimate outcome of the struggle between the Mughals and the Deccan states. - 9.1 INTRODUCTION - In Unit 8 of this Block you have learnt how the independent Sultanates of Ahmednagar, Bijapur, Golkonda, Berar and Bidar had been established in the Deccan. We have already discussed the development of these states and their relations to each other (Unit 8). Here our focus would be on the Mughal relations with the Deccan states. The Deccan policy of the Mughals was not determined by any single factor. The strategic importance of the Decen states and the administrative and economic necessity of the Mughal empire largely guided the attitude of the Mughal rulers towards the Deccan states. Babar, the first Mughal ruler, could not establish any contact with Deccan because of his pre-occupations in the North. Still, his conquest of Chanderi in 1528 had brought the Mugllal empire close to the northern cbnfines of Malwa. -

African Diaspora in Medieval Deccan: a Historical Analysis from 14Th to 17Th Century Dr

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 10 Issue 10, October 2020 ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gate as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A African Diaspora in Medieval Deccan: A Historical Analysis from 14th to 17th century Dr. Surendra Kumar, Department of History, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Delhi This Paper was Presented in International Conference organized by Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts(IGNCA), New Delhi on Oct 15, 2014 The African Diaspora in Medieval Deccan offers a new insight about space, political culture, ethnogenesis and Military Labour Market in History of India as well as it provides a new understanding of medieval India from perspective of regional History. This paper traces History of African Diaspora in Medieval Deccan from 14 to 17 century. Tracing issues of Migration in Medieval Deccan, it examines processes of ethnogenesis in African Diaspora and analyses role of space and political culture in shaping contours of ethnogenesis in Medieval Deccan. Further, the paper analyses dimensions of Military Labour market in Medieval Deccan in determining participation of African Diaspora and its impact on evolution of politics in Medieval Deccan. Although, the presence of African Diaspora in the Indian subcontinent has been dated since 10th century onwards, particularly participation in politics from Delhi Sultanate to Bengal is very well documented in primary sources of Ibn Battuta, Muhammad Qasim Ferishta, Jahangir and Others. -

Dynastic Lists and Genealogical Tables

DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES (1) The Bahamani Dynasty of the Deccan. (2) The Nizam Shahi Dynasty of Ahmadnagar. (3) The Adil Shahi Dynasty of Bijapur. (4) The Imad Shahi Dynasty of Berar. (5) The Qutb Shahi Dynasty of Golconda. (6) The Barid Shahi Dynasty of Bidar. (7) The Faruqi Dynasty of Khandesh. 440 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES THE BAHAMANI DYNASTY OF THE DECCAN Year of Accession Year of Accession A. H. A. D. 748 Ala-ud-din Bahman Shah 1347 759 Muhammad I 1358 776 Mujahid 1375 779 Daud 1378 780 Mahmud (wrongly called Muhammad II) . 1378 799 Ghiyas-ud-din 1397 799 Shams-ud-din 1397 800 Taj-ud-din-Firoz 1397 825 Ahmad, Vali 1422 839 Ala-ud-din Ahmad 1436 862 Humayun Zalim 1458 865 Nizam 1461 867 Muhammad III, Lashkari 1463 887 Mahmud 1482 924 Ahmad 1518 927 Ala-ud-din 1521 928 Wali-Ullah 1522 931 Kalimullah 1525 944 End of the dynasty 1538 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES 441 THE BAHAMANI DYNASTY OF THE DECCAN GENEALOGY (Figures in brackets denote the order of succession) 442 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES THE NIZAM SHAHI DYNASTY OF AHMADNAGAR Year of Accession Year of Accession A. H. A. D. 895 Ahmad Nizam Shah 1490 915 Burhan Nizam Shah I 1509 960 Husain Nizam Shah I 1553 973 Murtaza Nizam Shah I 1565 996 Husain Nizam Shah II 1588 997 Ismail Nizam Shah 1589 999 Burhan Nizam Shah II 1591 1001 Ibrahim Nizam Shah 1594 1002 (Ahmad-usurper) 1595 1003 Bahadur Nizam Shah 1595 1007 Murtaza Nizam Shah II 1599 1041 Husain Nizam Shah III 1631 1043 End of the Dynasty 1633 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES 443 444 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES THE ADIL SHAHI DYNASTY OF BIJAPUR Year of Accession Year of Accession A. -

Unit-1 T. S. Eliot : Religious Poems

UNIT-1 T. S. ELIOT : RELIGIOUS POEMS Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 ‘A Song for Simeon’ 1.3 ‘Marina’ 1.4 Let us sum up 1.5 Review Questions 1.6 A Select Bibliography 1.0 Objectives The present unit aims at acquainting you with some of T.S. Eliot’s poems written after his confirmation into the Anglo-Catholic Church of England in 1927. With this end in view, this unit takes up a close reading of two of his ‘Ariel Poems’ and focuses on some traits of his religious poetry. 1.1 Introduction Thomas Stearns Eliot was born on 26th September, 1888 at St. Louis, Missouri, an industrial city in the center of the U.S.A. He was the seventh and youngest child of Henry Ware Eliot and Charlotte Champe Stearns. He enjoyed a long life span of more than seventy-five years. His period of active literary production extended over a period of forty-five years. Eliot’s Calvinist (Puritan Christian) ancestors on father’s side had migrated in 1667 from East Coker in Somersetshire, England to settle in a colony of New England on the eastern coast of North America. His grandfather, W.G. Eliot, moved in 1834 from Boston to St. Louis where he established the first Unitarian Church. His deep academic interest led him to found Washington University there. He left behind him a number of religious writings. Eliot’s mother was an enthusiastic social worker as well as a writer of caliber. His family background shaped his poetic sensibility and contributed a lot to his development as a writer, especially as a religious poet. -

Indian Archaeology 1957-58 a Review

INDIAN ARCHAEOLOGY 1957-58 -A REVIEW EDITED BY A. GHOSH Director General of Archaeology in India DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI 1958 shillings Price Rs. 7.50 12 COPYRIGHT DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRINTED AT THE CORONATION PRI NTING works, DELHI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As in the four previous numbers of this annual Review^ this being the fifth one in the Series, ^11 the information and illustrations contained in the following pages have been received from different sotirces, viz. the officers of the Department of Archaeology of the Government of India and the heads of ^t]::ier institutions connected with the archaeological activities in the country, but for whose ready co- ^ Iteration it would have been impossible to give the Review any semblance of completeness. To all of my grateful thanks are due. I also acknowledge the valuable help I have received from my Colleagues in the Department in editing the Review and seeing it through the Press. In a co-operative endeavour of this nature, it is impossible for the editor or anybody else to ^ssiame full responsibility for the absolute accuracy of all the information and particularly for the inter- pretation of the archaeological material brought to light. Further, the possibility of editorial slips hav- crept in may not also be entirely ruled out, ihovgh it hrs teen our best endeavour to avoid them. ISfjEW Delhi : A. GHOSB 21st August 1958 Director General of Archaeology in India CONTENTS PAGE I. General ... ... I n. ... Explorations and excavations ... ... -s III. Epigraphy ... ... ... __ 54 IV. Numismatics and treasure- trove .. -

Review of Research Impact Factor : 5.7631(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 5 | feBRUaRY - 2019 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ TOURISM AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF VIJAYAPURA AND NORTH GOA DISTRICT Yallama Chawan1 and Dr. R. V. Gangshetty2 1Research Scholar, Department of Economics, Akkamahadevi Women’s university Vijayapura. 2Associate professor, Dept of Economics, Akkamahadevi women’s University Vijayapura. ABSTRACT : From ancient period India is famous for its culture, heritage and at the same time India is known for tourism. Tourists are attracted towards India only because of its natural beauty, historical places, arts and crafts. India can always boast of its rich cultural heritage. Travel and tourism in India is an integral part of Indian tradition and culture. In ancient times travel was primarily for pilgrimage as the holy place dotting the country attracted people from different parts of the world. People also travel to participate in large scale feast, fairs and festivals in different parts of country. In such a background cultural tradition was developed where Atithi Devo Bhava (the guest is god) and Vasudhaiva Kutumbhakam (the world is one family) became by wards of Indian social behavior. KEYWORDS : Tourism, pilgrimage, Vasudhaiva, Atithi, heritage. INTRODUCTION: From ancient period India is famous for its culture, heritage and at the same time India is known for tourism. Tourists are attracted towards India only because of its natural beauty, historical places, arts and crafts. India can always boast of its rich cultural heritage. Travel and tourism in India is an integral part of Indian tradition and culture. -

S.S Std10 Chap6

Shree H.J. Gajera Madhyamik ane Uchchatar Madhyamik Shala,Utran. Sub:Social Science Std:10 India is a nation which is well known for its wide range of Historical Monuments. The country is a beautiful amalgamation of diverse culture, religions, traditions and customs. People call India as ‘Sone Ki Chidiya’ as India is a land of beautiful ancient architecture which attracts people’s attention and makes them anxious to know more about them in detail. The Monuments of India are the result of long period of invasion. Historical Places of India represents the great achievement in art and architecture. These monuments were built by Indian Kings as a symbol of their glory in wars or to represent the beautiful cultural heritage of India. So, here in this article, we have gathered all the information regarding the Famous Monuments of India and the history behind the formation of these places. Let’s explore all these in detail and fill up your knowledge bucket. Famous Historical Monuments of India-Reflecting Indian Cultural Heritage! The royal past and the colonial rule in the different regions of the Country have left the country with a wide range of Ancient Monuments of India which are of great significance. The region-wise knowledge of these monuments will help you to explore the history of the nation with better understanding. So, let’s have a look at these monuments. North Indian Monuments / Historical Places in India The Northern part of India is rich in cultural heritage which attracts tourists through the beauty of its designed monuments. North Indian cities like Agra, Jaipur, Delhi (known as a golden trio of North India) offers a large tourist attraction. -

Adopt a Heritage Project - List of Adarsh Monuments

Adopt a Heritage Project - List of Adarsh Monuments Monument Mitras are invited under the Adopt a Heritage project for selecting/opting monuments from the below list of Adarsh Monuments under the protection of Archaeological Survey of India. As provided under the Adopta Heritage guidelines, a prospective Monument Mitra needs to opt for monuments under a package. i.e Green monument has to be accompanied with a monument from the Blue or Orange Category. For further details please refer to project guidelines at https://www.adoptaheritage.in/pdf/adopt-a-Heritage-Project-Guidelines.pdf Please put forth your EoI (Expression of Interest) for selected sites, as prescribed in the format available for download on the Adopt a Heritage website: https://adoptaheritage.in/ Sl.No Name of Monument Image Historical Information Category The Veerabhadra temple is in Lepakshi in the Anantapur district of the Indian state of Andhra Virabhadra Temple, Pradesh. Built in the 16th century, the architectural Lepakshi Dist. features of the temple are in the Vijayanagara style 1 Orange Anantpur, Andhra with profusion of carvings and paintings at almost Pradesh every exposed surface of the temple. It is one of the centrally protected monumemts of national importance. 1 | Page Nagarjunakonda is a historical town, now an island located near Nagarjuna Sagar in Guntur district of Nagarjunakonda, 2 the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, near the state Orange Andhra Pradesh border with Telangana. It is 160 km west of another important historic site Amaravati Stupa. Salihundam, a historically important Buddhist Bhuddist Remains, monument and a major tourist attraction is a village 3 Salihundum, Andhra lying on top of the hill on the south bank of the Orange Pradesh Vamsadhara River. -

Answered On:02.08.2001 Encroachment Unauthorised Construction in Monuments Chandra Nath Singh;Dilip Kumar Mansukhlal Gandhi

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA TOURISM AND CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:1708 ANSWERED ON:02.08.2001 ENCROACHMENT UNAUTHORISED CONSTRUCTION IN MONUMENTS CHANDRA NATH SINGH;DILIP KUMAR MANSUKHLAL GANDHI Will the Minister of TOURISM AND CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) the name of protected monuments de-encroached successfully by the Government during the last three years; till date location- wise; (b) the details of protected monuments still under encroachment/unauthorised constructed, location-wise; (c) the problems likely to be faced by the Government in removing such encroachments; and (d) the steps being taken/proposed to be taken by the Government for removing encroachments/unauthorised construction from the protected monuments? Answer MINISTER OF TOURISM AND CULTUE (SHRI ANANTH KUMAR) (a)&(b) A list is enclosed at annexure I and II. (c ) The litigation involved in such cases is often time consuming. (d ) Apart from taking legal action, active co-operation of the State Governments at various levels is sought regularly. The Archaeological Survey of India had also stepped up its programme of fencing the protected monuments and sites. ANNEXURE-I ANNEXURE REFFERED TO PART `A` OF THE UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.1708 TO BE ANSWERED ON 2.8.2001 LIST OF NAME OF CENTRALLY PROTECTED MONUMENTS DE-ENCROACHED DURING THE LAST THREE YEARS Name of Monument Location/State CALCUTTA CIRCLE 1. Hazarduari Palce and Imambara(from the area within fencing) Murshidabad, West.Bengal 2. John Pierce`s tomb Midnapore, West Bengal BHOPAL CIRCLE 1. Shiv Temple, Bhojpur District Raisen(Madhya Pradesh) 2. Monuments at Mandu, viz. Taveli Mahal, Jama Masjid and Daria Khan Tomb Distt.Dhar, Madhya Pradesh PATNA CIRCLE 1. -

Chapter 10—Mediaeval Administration and Social

CHRONOLOGY 1296 Ala-ud-din invades the kingdom of Devagiri, in the Deccan (p. 1). 1303 Failure of an expedition to Warangal (p. 2). 1306-1307 Expedition of Kafur (Malik Naib) to Devagiri (p. 3). 1310 Expedition to Warangal. Prataparudraveda II submits and pays tribute (p. 3). 1311 Expedition, under Malik Naib, into the Peninsula. Capture of Dvaravatipura and Madura. Mosque built at Rames-waram. Submission of the Pandya and Kerala kingdoms (pp. 4 and 5). 1311 Death of Ramchandra and accession of Shankardev (p. 6). 1316 Death of ' Ala-ud-din and accession of Shihab-ud-din ' Umar. Death of Malik Naib, Deposition of Umar and accession of Qutb-ud-din Mubarak (p. 7). 1318 Mubarak's expedition to Devagiri. Capture and death of Harpal (p. 7). 1321 Expedition to Warangal under Muhammad Jauna (Ulugh Khan) (pp. 8, 9). 1323 Second expedition to Warangal under Muhammad. Capture of Prataparudradeva II. (p. 9). 1327 Rebellion of Gurshasp (p. II). 1327 Capital transferred from Delhi to Daulatabad (p. 11). 1337 Rebellion of Nusrat Khan at Bidar (pp. 11, 12). 1340 Rebellion of Ali Shah Natthu in the Deccan (p. 12). 1346 Rebellion of the Centurions in Gujarat. Muhammad leaves Delhi for Gujarat, and suppresses the rebellion (p. 12). 1346 Rebellion in Daulatabad: Ismail Mukh proclaimed king of the Deccan. Muhammad besieges Daulatabad (p. 13). 1347 Ala-ud-din Bahman Shah proclaimed king of the Deccan. (p. 13). 1353 Rebellion of Muhammad Alam, Ali Lachin and Fakhruddin Muhurdar at Sagar (p. 15). 1358 Death of Bahman Shah and accession of Muhammad I Bahamani in the Deccan. -

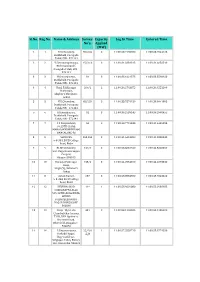

Sl.No. Reg.No. Name & Address Survey No's. Capacity Applied (MW

Sl.No. Reg.No. Name & Address Survey Capacity Log In Time Entered Time No's. Applied (MW) 1 1 H.V.Chowdary, 65/2,84 3 11:00:23.7195700 11:00:23.7544125 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 2 2 Y.Satyanarayanappa, 15/2,16 3 11:00:31.3381315 11:00:31.6656510 Bheemunikunte, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 3 3 H.Ramanjaneya, 81 3 11:00:33.1021575 11:00:33.5590920 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 4 4 Hanji Fakkirappa 209/2 2 11:00:36.2763875 11:00:36.4551190 Mariyappa, Shigli(V), Shirahatti, Gadag 5 5 H.V.Chowdary, 65/2,84 3 11:00:38.7876150 11:00:39.0641995 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 6 6 H.Ramanjaneya, 81 3 11:00:39.2539145 11:00:39.2998455 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 7 7 C S Nanjundaiah, 56 2 11:00:40.7716345 11:00:41.4406295 #6,15TH CROSS, MAHALAKHSMIPURAM, BANGALORE-86 8 8 SRINIVAS, 263,264 3 11:00:41.6413280 11:00:41.8300445 9-8-384, B.V.B College Road, Bidar 9 9 BLDE University, 139/1 3 11:00:23.8031920 11:00:42.5020350 Smt. Bagaramma Sajjan Campus, Bijapur-586103 10 10 Basappa Fakirappa 155/2 3 11:00:44.2554010 11:00:44.2873530 Hanji, Shigli (V), Shirahatti Gadag 11 11 Ashok Kumar, 287 3 11:00:48.8584860 11:00:48.9543420 9-8-384, B.V.B College Road, Bidar 12 12 DEVUBAI W/O 11* 1 11:00:53.9029080 11:00:55.2938185 SHARANAPPA ALLE, 549 12TH CROSS IDEAL HOMES RAJARAJESHWARI NAGAR BANGALORE 560098 13 13 Girija W/o Late 481 2 11:00:58.1295585 11:00:58.1285600 ChandraSekar kamma, T105, DNA Opulence, Borewell Road, Whitefield, Bangalore - 560066 14 14 P.Satyanarayana, 22/*/A 1 11:00:57.2558710 11:00:58.8774350 Seshadri Nagar, ¤ltĔ Bagewadi Post, Siriguppa Taluq, Bellary Dist, Karnataka-583121 Sl.No.