Reconsidering Local History: Some Facts, Some Observations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odisha District Gazetteers Nabarangpur

ODISHA DISTRICT GAZETTEERS NABARANGPUR GOPABANDHU ACADEMY OF ADMINISTRATION [GAZETTEERS UNIT] GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ODISHA DISTRICT GAZETTEERS NABARANGPUR DR. TARADATT, IAS CHIEF EDITOR, GAZETTEERS & DIRECTOR GENERAL, TRAINING COORDINATION GOPABANDHU ACADEMY OF ADMINISTRATION [GAZETTEERS UNIT] GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ii iii PREFACE The Gazetteer is an authoritative document that describes a District in all its hues–the economy, society, political and administrative setup, its history, geography, climate and natural phenomena, biodiversity and natural resource endowments. It highlights key developments over time in all such facets, whilst serving as a placeholder for the timelessness of its unique culture and ethos. It permits viewing a District beyond the prismatic image of a geographical or administrative unit, since the Gazetteer holistically captures its socio-cultural diversity, traditions, and practices, the creative contributions and industriousness of its people and luminaries, and builds on the economic, commercial and social interplay with the rest of the State and the country at large. The document which is a centrepiece of the District, is developed and brought out by the State administration with the cooperation and contributions of all concerned. Its purpose is to generate awareness, public consciousness, spirit of cooperation, pride in contribution to the development of a District, and to serve multifarious interests and address concerns of the people of a District and others in any way concerned. Historically, the ―Imperial Gazetteers‖ were prepared by Colonial administrators for the six Districts of the then Orissa, namely, Angul, Balasore, Cuttack, Koraput, Puri, and Sambalpur. After Independence, the Scheme for compilation of District Gazetteers devolved from the Central Sector to the State Sector in 1957. -

Unit-1 T. S. Eliot : Religious Poems

UNIT-1 T. S. ELIOT : RELIGIOUS POEMS Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 ‘A Song for Simeon’ 1.3 ‘Marina’ 1.4 Let us sum up 1.5 Review Questions 1.6 A Select Bibliography 1.0 Objectives The present unit aims at acquainting you with some of T.S. Eliot’s poems written after his confirmation into the Anglo-Catholic Church of England in 1927. With this end in view, this unit takes up a close reading of two of his ‘Ariel Poems’ and focuses on some traits of his religious poetry. 1.1 Introduction Thomas Stearns Eliot was born on 26th September, 1888 at St. Louis, Missouri, an industrial city in the center of the U.S.A. He was the seventh and youngest child of Henry Ware Eliot and Charlotte Champe Stearns. He enjoyed a long life span of more than seventy-five years. His period of active literary production extended over a period of forty-five years. Eliot’s Calvinist (Puritan Christian) ancestors on father’s side had migrated in 1667 from East Coker in Somersetshire, England to settle in a colony of New England on the eastern coast of North America. His grandfather, W.G. Eliot, moved in 1834 from Boston to St. Louis where he established the first Unitarian Church. His deep academic interest led him to found Washington University there. He left behind him a number of religious writings. Eliot’s mother was an enthusiastic social worker as well as a writer of caliber. His family background shaped his poetic sensibility and contributed a lot to his development as a writer, especially as a religious poet. -

CHAPTER VIII the INTEGRATED out LOOK of the MARWARIS in the DISTRICTS UNDER STUDY Th

CHAPTER VIII THE INTEGRATED OUT LOOK OF THE MARWARIS IN THE DISTRICTS UNDER STUDY Th~ Marwaris are philanthropic by nature and this rare human quality is one of the chief reasons for success of Marwari entrepreneurship anywhere in India. Their cool headed and amiable temperament, their power of adaptabili ty and adjustability to any kind of circumstances~ envi ronment, whether regional or local, their exceptional sense of conciliation and assimilation - all these traits of their character helped them considerably in doing business in distant and unknown places, far away from their native land. However, human factors are conditioned, to some extent,by compulsions. The Marwaris are aware. that good public relations are a requisite for business transactions and that a rapport with the general public can best be estab lished by making cordial gesture. Their quick adoption of the local language helps them immensely in establishing this rapport. Initially, they used to migrate to a place in search of subsistence alone, keeping their womenfolk at home. So there had always been an identity crisis which they suffered from at the place of migration and to over- 344 come this crisis they thought it wise to mingle with the local people by participating in local festivals and attending social gatherings o.f other communi ties who lived there. Thereby they tried to join the mainstream of the society. At times, this attempt at social merger was per- haps only half-hearted in view of the fact that a sense of uncertainty in business always occupied their minds which were also filled with concern for their families particu- i larl:y for their womenfolk. -

Twenty Fifth Annual Report Annual Report 2017-18

TWENTY FFIFTHIFTH ANNUAL REPORT 20172017----18181818 ASSAM UNIVERSITY Silchar Accredited by NAAC with B grade with a CGPS OF 2.92 TWENTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 REPORT 2017-18 ANNUAL TWENTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 PUBLISHED BY INTERNAL QUALITY ASSURANCE CELL, ASSAM UNIVERSITY, SILCHAR Annual Report 2017-18 ASSAM UNIVERSITY th 25 ANNUAL REPORT (2017-18) Report on the working of the University st st (1 April, 2017 to 31 March, 2018) Assam University Silchar – 788011 www.aus.ac.in Compiled and Edited by: Internal Quality Assurance Cell Assam University, Silchar | i Annual Report 2017-18 STATUTORY POSITIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY (As on 31.3.2018) Visitor : Shri Pranab Mukherjee His Excellency President of India Chief Rector : Shri Jagdish Mukhi His Excellency Governor of Assam Chancellor : Shri Gulzar Eminent Lyricist and Poet Vice-Chancellor : Prof Dilip Chandra Nath Deans of Schools: (As on 31.3.2018) Prof. G.P. Pandey : Abanindranath Tagore School of Creative Arts & Communication Studies Prof. Asoke Kr. Sen : Albert Einstein School of Physical Sciences Prof. Nangendra Pandey : Aryabhatta School of Earth Sciences Prof. Geetika Bagchi : Ashutosh Mukhopadhyay School of Education Prof. Sumanush Dutta : Deshabandhu Chittaranjan School of Legal Studies Prof. Dulal Chandra Roy : E. P Odum School of Environmental Sciences Prof. Supriyo Chakraborty : Hargobind Khurana School of Life Sciences Prof. Debasish Bhattacharjee : Jadunath Sarkar School of Social Sciences Prof. Apurbananda Mazumdar : Jawarharlal Nehru School of Management Prof. Niranjan Roy : Mahatma Gandhi School of Economics and Commerce Prof. W. Raghumani Singh : Rabindranath Tagore School of Indian Languages and Cultural Studies Prof. Subhra Nag : Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan School of Philosophical Studies Prof. -

Gaur As 'Monument': the Making of an Archive and Tropes of Memorializing

Gaur as ‘Monument’: The Making of an Archive and Tropes of Memorializing Parjanya Sen In his book The Ruins of Gour Henry Creighton, one of the first among a series of early English explorers to the site describes Gaur as ‘an uninhabited waste’, ‘concealed in deep jungle, and situated in one of the least civilized districts of the Bengal Presidency’.1 Describing the ruins in hyperbolic rhetoric, Creighton writes: In passing through so large an extent of formal grandeur, once the busy scene of men, nothing presents itself but these few remains. Trees and high grass now fill up the space, and shelter a variety of wild creatures, bears, buffaloes, deer, wild hogs, snakes, monkies, peacocks, and the common domestic fowl, rendered wild for want of an owner. At night the roar of the tiger, the cry of the peacock, and the howl of the jackals, with the accompaniment of rats, owls, and trouble-some insects, soon become familiar to the few inhabitants still in its neighbourhood.2 A similar rhetoric may be found in Fanny (Parlby) Parks’s description of Gaur in her memoirs. Parks travelled extensively in India during the 1830s. On visiting Gaur, she appears to have been delighted by these ‘picturesque’ ruins amidst a ‘country’ ‘remarkably beautiful’, and enamoured by the site, covered with the silk cotton tree, the date palm, and various other trees; and there was a large sheet of water, covered by high jungle grass, rising far above the heads of men who were on foot. On the clear dark purple water of a large tank floated the lotus in the wildest -

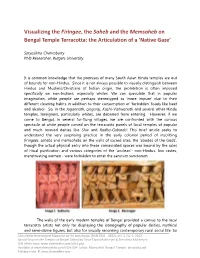

Visualizing the Firingee, the Saheb and the Memsaheb on Bengal Temple Terracotta: the Articulation of a ‘Native Gaze’

Visualizing the Firingee, the Saheb and the Memsaheb on Bengal Temple Terracotta: the Articulation of a ‘Native Gaze’ Satyasikha Chakraborty PhD Researcher, Rutgers University It is common knowledge that the premises of many South Asian Hindu temples are out of bounds for non-Hindus. Since it is not always possible to visually distinguish between Hindus and Muslims/Christians of Indian origin, the prohibition is often imposed specifically on non-Indians, especially whites. We can speculate that in popular imagination, white people are perhaps stereotyped as ‘more impure’ due to their different cleaning habits in addition to their consumption of ‘forbidden’ foods like beef and alcohol. So, in the Jagannath, Lingaraj, Kashi-Vishwanath and several other Hindu temples, foreigners, particularly whites, are debarred from entering. However, if we come to Bengal, in several far-flung villages, we are confronted with the curious spectacle of white people carved on the terracotta panels of local temples of popular and much revered deities like Shiv and Radha-Gobindo! This brief article seeks to understand the very surprising practice in the early colonial period of inscribing firingees, sahebs and memsahebs on the walls of sacred sites, the ‘abodes of the Gods’, though the actual physical entry into these consecrated spaces was bound by the rules of ritual purification and various categories of the ‘unclean’- non-Hindus, low castes, menstruating women - were forbidden to enter the sanctum sanctorum. The walls of the early modern temples of Bengal provided a canvas to the local terracotta artists not only for displaying the iconography of popular deities, mythical and semi-divine figures, but also for visually recording contemporary rural social life. -

Representations of the “Rural” in India from the Colonial to the Post-Colonial

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 21 | 2019 Representations of the “Rural” in India from the Colonial to the Post-Colonial Joël Cabalion and Delphine Thivet (dir.) Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/5376 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.5376 ISSN: 1960-6060 Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic reference Joël Cabalion and Delphine Thivet (dir.), South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 21 | 2019, « Representations of the “Rural” in India from the Colonial to the Post-Colonial » [Online], Online since 10 September 2019, connection on 09 May 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/5376 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj.5376 This text was automatically generated on 9 May 2020. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. 1 EDITOR'S NOTE SAMAJ-EASAS Series Series editors: Alessandra Consolaro, Sanjukta Das Gupta and José Mapril. This thematic issue is the seventh in a series of issues jointly co-edited by SAMAJ and the European Association for South Asian Studies (EASAS). More on our partnership with EASAS here. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 21 | 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Who Speaks for the Village? Representing and Practicing the “Rural” in India from the Colonial to the Post-Colonial Joël Cabalion and Delphine Thivet Villages in the City: The Gramastha Mandals of Mumbai Jonathan Galton Politics of a Transformative Rural: Development, Dispossession and Changing Caste- Relations -

Annual Report 2015-2016

VISVA-BHARATI Annual Report 2015-2016 Santiniketan 2016 YATRA VISVAM BHAVATYEKANIDAM (Where the World makes its home in a single nest) “ Visva-Bharati represents India where she has her wealth of mind which is for all. Visva-Bharati acknowledges India's obligation to offer to others the hospitality of her best culture and India's right to accept from others their best ” -Rabindranath Tagore Contents Chapter I ................................................................i-v Department of Biotechnology...............................147 From Bharmacharyashrama to Visva-Bharati...............i Centre for Mathematics Education........................152 Institutional Structure Today.....................................ii Intergrated Science Education & Research Centre.153 Socially Relevant Research and Other Activities .....iii Finance ................................................................... v Kala Bhavana.................................................157 -175 Administrative Staff Composition ............................vi Department of Design............................................159 University At a Glance................................................vi Department of Sculpture..........................................162 Student Composition ................................................vi Department of Painting..........................................165 Teaching Staff Composition.....................................vi Department of Graphic Art....................................170 Department of History of Art..................................172 -

2015 Williams Richard 113649

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Hindustani music between Awadh and Bengal, c.1758-1905 Williams, Richard David Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 Hindustani music between Awadh and Bengal, c.1758-1905 RICHARD DAVID WILLIAMS Submitted in FulFilment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor oF Philosophy KING’S COLLEGE LONDON DECEMBER 2014 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the interaction between Hindustani and Bengali musicians and their patrons over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the convergence of Braj, Persianate, and Bengali musical cultures in Bengal after 1856. -

2005 Annual Report.Pdf

jesus college • cambridge one hundred and first annual report 2005 jesus college • cambridge one hundred and first annual report 2005 photo: frances willmoth Above, two men paddling in a boat; below, Jonah emerges from the fish’s mouth and clutches a tree From July to December this year the Fitzwilliam Museum is showing a most magnificent exhibition of illuminated manuscripts, many of which are from college collections. Jesus was not asked to lend anything for this exhibition – ‘as most of our manuscripts are of the working kind and not elaborately decorated’. Some of the college manuscripts, however, do have illuminations. A 13th century Holy Bible in the college’s collection (Q.A.11: no. 11 in M. R. James’ 1895 catalogue) not only has beautiful writing but ‘historiated initials of more than usual interest’. So that readers can see something of what the Fitzwilliam has missed, this year’s Annual Report carries a number of illustrations taken from that Bible. COPYRIGHT This publication is protected by international copyright law. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems – without the prior permission of the copyright holders, except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. contents Message from the Master 5 The College Year 2004–5 7 College News 7 Domestic Bursar’s Notes 13 The Old Library and College Archives 15 Chapel 17 Chapel Music 19 Art 20 Sculpture in the Close 21 Development Office 24 Development Director’s Report 24 Society of St Radegund 24 Bequests 24 Report of Events 24 Calendar of Events 2005–6 30 M.A. -

Chapter-6 Cultural Changes

266 Chapter-6 Cultural Changes Culture is a very much big spectrum to study. Culture is generally defined as the way of life, especially the general customs and beliefs of a particular group of people at a particular time. So in study of demography the aspect of culture must come in the way of discussion and the demographic changes also leading to the cultural changes drove us to examine and indicate those changes so that any crisis or question emerged from that changes may be conciliated indicating the basics of those changes. In this context the study of cultural change from historical perspective is of a great significance. As we have seen a voluminous and characterized changes in demography happened throughout a long period of 120 years from 1871 to 1991 census year, there might be changes happened in the cultural ingredients of the people of North Bengal. Religion, Caste, language and literature are regarded the basic ingredients of culture. S.N.Ghosh, Director of Census Operations, West Bengal wrote that ‘Religion is an important and perhaps the basic cultural characteristics of the population.’1 On the other it has been opined by Sri A. Mitra that ‘The caste system provides the individual member of a caste with rules which must be by him observed in the matters of food, marriage, divorce, birth, initiation, and death.2 This exemplifies the role of Caste in cultural practices in human life. In this chapter I shall examine the changes in religious and caste composition of demography of North Bengal for the whole period of my discussion and highlight over the changes in numerical growth of persons speaking different languages and then I shall try to indicate to the changes in cultural habits and practices of emerging North Bengal people. -

Cultural Ecology of the Fishing Communities

CHAPTER 3 CULTURAL ECOLOGY OF THE FISHING COMMUNITIES This chapter deals with cultural ecology of the three traditional fishing communities of the Barak Valley; viz., Patni, Kaivartya and Mahimal. Each one of the communities Is engaged with fishing in the Shonebeel and the Barak river fisheries. In the Shonebeel fishery, they are inhabiting Devadwar, Kalyanpur and Belala. While in the Barak river they are inhabiting Netaji Nagar, Radha Nagar and Balighat respectively. The communities and their cultural ecology have been discussed to understand how the ecological conditions (environment / natural setting and resources) have shaped their culture (way of life) in the Barak Valley, specially under impact of fishing, on the one hand, and how cultural practices and products conceive and modify their environment and occupations. Hence, there is a particular cultural setting of the interactions between the fishing communities and their environment, and the setting determine the nature and range of the interactions. With these views, cultural ecology of the communities is presented in the following discussion. THE COMMUNITIES The three communites - Patni, Kaivartya, Mahimal - derived their occupations, lifestyles and social status from the fish resource. In order to understand their cultural ecology the historical origin and interaction pattern of the communities needs to be probed. 74 The Patni The word 'Patni' refers to the people coming from Patna. The Patni believe that they moved from Patna (Bihar) to Jaldhup village (Bangladesh) in the 16*^ century for trading. But in some natural calamity they lost everything and they had to stay permanently in this area. They took up boat sailing for livelihood and have therefore come to be recognized as the boatmen (Majhis) and not as traders.