A Comparative Study of Livestock's Name Between Ancient And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One University One Village 一專一村

ONE UNIVERSITY ONE VILLAGE 一專一村 1U1V Newsletter, Volume 3, August 2018 “One University One Village” International Earth Building Festival @Kunming The first International Earth Building Festival, jointly organized by the 1U1V team of The Chinese University of Hong Kong and Faculty of Architecture and City Planning, Kunming University of Science and Technology, came to a close on June 26, 2018. The event lasted for eight days. It was attended by a total of 24 participants from various countries, such as Canada, Japan, USA, Inner Mongolia and Ningxia. During the event, the 1U1V team invited two French specialists in earth construction— Mr. Marc Auzet and Ms. Juliette Goudy— and Prof. Bai Wenfeng, who specializes in the seismic performance study of building structures at Kunming University of Science and Technology, to provide professional guidance. This Festival covered three aspects: rammed-earth construction materials, rammed-earth construction technology and the practice of earth construction. It aims to provide an opportunity for participants to get close to the construction site of an earth building and deepen their understanding of the material and method. The process is both intelligently and physically challenging. Apart from attending lectures about soil and visiting traditional earth building villages, the participants also learnt about the construction condition of the 1U1V Earth Building Research Centre. Furthermore, they were taught to distinguish soil composition, test it, make adobe bricks with different proportions, and build self-design structures (including partition walls, bars and seats) with clay of different properties. Participants have shown their endurance to hardship through their sweat. Due to rain, some activities were held indoors. -

County, Province 包装厂中文名chinese Name of Packing House

序号 注册登记号 所在地 Location: 包装厂中文名 包装厂英文名 包装厂中文地址 包装厂英文地址 Numbe Registered Location County, Province Chinese Name of Packing house English Name of Packing house Address in Chinese Address in English r Number 1 北京平谷 PINGGU,BEIJING 北京凤凰山投资管理中心 BEIJING FENGHUANGSHAN INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT CENTER 平谷区峪口镇 YUKOU,PINGU DISTRICT,BEIJING 1100GC001 2 北京平谷 PINGGU,BEIJING 北京东四道岭果品产销专业合作社 BEIJING DONGSIDAOLING FRUIT PRODUCTION AND MARKETING PROFESSIONNAL COOPERATIVES平谷区镇罗营镇 ZHENLUOYING,PINGGU DISTRICT,BEIJING 1100GC002 TIANJIN JIZHOU DEVELOPMENT ZONE, WEST IN ZHONGCHANG SOUTH ROAD, NORTH 3 天津蓟州区 JIZHOU,TIANJIN 天津蓟州绿色食品集团有限公司 TIANJIN JIZHOU GREEN FOOD GROUP CO., LTD. 天津市蓟州区开发区中昌南路西、京哈公路北IN JING-HA ROAD 1200GC001 4 河北辛集 XINJI,HEBEI 辛集市裕隆保鲜食品有限责任公司果品包装厂XINJI YULONG FRESHFOOD CO.,LTD. PACKING HOUSE 河北省辛集市南区朝阳路19号 N0.19 CHAOYANG ROAD, SOUTH DISTRICT OF XINJI CITY, HEBEI PROVINCE 1300GC001 5 河北辛集 XINJI,HEBEI 河北天华实业有限公司 HEBEI TIANHUA ENTERPRISE CO.,LTD. 河北省辛集市新垒头村 XINLEITOU VILLAGE,XINJI CITY,HEBEI 1300GC002 6 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 河北鲜鲜农产有限公司 HEBEI CICI CO., LTD. 河北省晋州市工业路33号 NO.33 GONGYE ROAD,JINZHOU,HEBEI,CHINA 1300GC004 7 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 晋州天洋贸易有限公司 JINZHOU TIANYANG TRADE CO,. LTD. 河北省晋州市通达路 TONGDA ROAD, JINZHOU CITY,HEBEI PROVINCE 1300GC005 8 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 河北省晋州市长城经贸有限公司 HEBEI JINZHOU GREAT WALL ECONOMY TRADE CO.,LTD. 河北省晋州市马于开发区 MAYU,JINZHOU,HEBEI,CHINA 1300GC006 9 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 石家庄市丰达金润农产品有限公司 SHIJIAZHUANG GOLDEN GLORY AGRICULTURAL CO.,LTD. 晋州市马于镇北辛庄村 BEIXINZHUANG,JINZHOU,HEBEI,CHINA 1300GC007 10 河北赵县 ZHAO COUNTY,HEBEI 河北嘉华农产品有限责任公司 HEBEI JIAHUA -

Towards Eliminating Perinatal Transmission of HIV, Syphilis and Hepatitis B in Yunnan a Case Study, 2005–2012

Towards eliminating perinatal transmission of HIV, syphilis and hepatitis B in Yunnan A case study, 2005–2012 Yunnan AIDS Prevention and Control Bureau Towards eliminating perinatal transmission of HIV, syphilis and hepatitis B in Yunnan A case study, 2005–2012 Yunnan AIDS Prevention and Control Bureau WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Towards eliminating perinatal transmission of HIV, syphilis and hepatitis B in Yunnan: a case study, 2005-2012 1. HIV infections – prevention and control. 2. Hepatitis B. 3. Syphilis, Congenital. I. World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. ISBN 978 92 9061 696 2 (NLM Classification: WC 503.6) © World Health Organization 2015 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO web site (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). For WHO Western Pacific Regional Publications, request for permission to reproduce should be addressed to Publications Office, World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific, P.O. Box 2932, 1000, Manila, Philippines, fax: +632 521 1036, e-mail: [email protected] The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

One University One Village 一專一村

ONE UNIVERSITY ONE VILLAGE 一專一村 1U1V Newsletter, Volume 5, September 2020 The 1U1V programme under the COVID-19 outbreak In 2020, the spread of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Rammed Earth Houses affected the whole country and factories, schools and offices 23 nos. (completed) were forced to be shut down in many places with various 75 nos.(in progress) economic activities coming to a standstill. Fortunately, as 43 nos. (planned) 1U1V team’s operation mode in rural villages is different, some self-construction projects in the villages continued under the pandemic. For example, Yi people in the Baipoxiang of Miyi County have been building their own houses after the Chinese New Year. Except for some of the materials that must be brought from somewhere outside the villages, most of the construction materials can be obtained on-site in sufficient quantities, and thus the rammed earth walls can be built according to the original plan. This proved that the strategy of “local materials, local technology and Village Rebuilding Village Improvement local labour” is of high flexibility and strong resilience even Demonstration 1 no. (completed) under such special circumstances. 2 nos. (completed) Work & Achievement in Six Years Research & Development Centre# Yi Xin Qiao 1 no. (completed) 9 nos. (completed) # The Research and Development Centre for Rural Vitalization in Yunnan has been completed and it has conducted soil analysis, materials testing and artisan training simultaneously. More academic activities, rural architects-in-residence and internships will be launched when the COVID-19 is over. Others : Artisan Training: trained over 100 artisans, including 26 women, and five independent construction teams (including one women team) Awards: 12 international and local awards 1U1V Scholarship: 1 recipient Books: 3 nos. -

A New Crested Theropod Dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of Yunnan

第55卷 第2期 古 脊 椎 动 物 学 报 pp. 177-186 2017年4月 VERTEBRATA PALASIATICA figs. 1-3 A new crested theropod dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of Yunnan Province, China WANG Guo-Fu1,2 YOU Hai-Lu3,4* PAN Shi-Gang5 WANG Tao5 (1 Fossil Research Center of Chuxiong Prefecture, Yunnan Province Chuxiong, Yunnan 675000) (2 Chuxiong Prefectural Museum Chuxiong, Yunnan 675000) (3 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences Beijing 100044 * Corresponding author: [email protected]) (4 College of Earth Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences Beijing 100049) (5 Bureau of Land and Resources of Lufeng County Lufeng, Yunnan 650031) Abstract A new crested theropod, Shuangbaisaurus anlongbaoensis gen. et sp. nov., is reported. The new taxon is recovered from the Lower Jurassic Fengjiahe Formation of Shuangbai County, Chuxiong Yi Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan Province, and is represented by a partial cranium. Shuangbaisaurus is unique in possessing parasagittal crests along the orbital dorsal rims. It is also distinguishable from the other two lager-bodied parasagittal crested Early Jurassic theropods (Dilophosaurus and Sinosaurus) by a unique combination of features, such as higher than long premaxillary body, elevated ventral edge of the premaxilla, and small upper temporal fenestra. Comparative morphological study indicates that “Dilophosaurus” sinensis could potentially be assigned to Sinosaurus, but probably not to the type species. The discovery of Shuangbaisaurus will help elucidate the evolution of basal theropods, especially the role of various bony cranial ornamentations had played in the differentiation of early theropods. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

Tin from Myanmar – a Scenario for Applying the European Union Regu- Lation on Supply Chain Due Diligence

Commodity TopNews Fakten ● Analysen ● Wirtschaftliche Hintergrundinformationen 61 TIN FROM MYANMAR – A SCENARIO FOR APPLYING THE EUROPEAN UNION REGU- LATION ON SUPPLY CHAIN DUE DILIGENCE Christian Heimig 1, Philip Schütte 2, Gudrun Franken 2, Christoph Klein 3 Abb. 1:: Small-scale miners at the Mawchi tin mine, central Myanmar (photo: BGR). INTRODUCTION Starting from January 1, 2021, European Union including, among others, conflict financing, the (EU)-based importers of tin, tantalum and tungs- worst forms of child labor and human rights vi- ten, their ores, and gold are required to comply olations. To this end, the OECD guidance defi- with the EU regulation on supply chain due dili- nes a five-step due diligence framework, which gence (EU, 2017). The EU regulation is based on has been integrated into the EU regulation. The- the OECD due diligence guidance for responsib- se steps include establishing strong management le supply chains. The contents of this guidance systems, identifying and responding to supply provide a framework for companies to identify chain risks, carrying out independent third-party and mitigate risks in their mineral supply chains audits at certain points in the supply chain, and public reporting on due diligence implementation (OECD, 2016). 1 Formerly Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources, presently at Südwestdeutsche Salzwerke AG 2 Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources 3 Formerly Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources, presently at KPMG AG Wirtschaftsprüfungsgesellschaft 2 Commodity TopNews The US Dodd-Frank Act, enacted in 2010, al- oned experts to develop an indicative global list ready defines certain sourcing requirements for of such areas, companies remain responsible for so-called conflict minerals. -

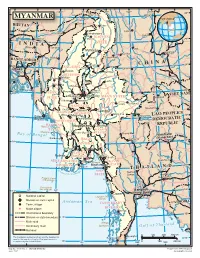

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

The World Bank

Documen; of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No. P-6821-CHA mEMORANDUMAND RECOMMENDATION OF THE PRESIDENT OF TRE INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT AND THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENTASSOCIATION TO THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS ON A PROPOSED LOAN OF $125 MILLION AND A PROPOSED CREDIT OF SDR 17.4 MILLION TO THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA FOR A YUNNAN ENVIRONMENT PROJECT May 28, 1996 This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performnanceof their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of May 1, 1996) Currency = Renminbi Currency Unit = Yuan (Y) Y 1.00 = $0.12 $1.00 = Y 8.3 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES Metric System PRINCIPAL ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS USED DEAP - Dianchi Environmental Action Plan EPB - Envirotu-nental Protection Bureau EPCSL - Environmental Pollution Control Subloans LIBOR - London Interbank Borrowing Rate MCon - Ministry of Construction NEPA - National Environmental Protection Agency YPG - Yunnan Provincial Government GOVERNMENT FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 FOROFFICIAL USE ONLY CHINA YUNNAN ENVIRONMENT PROJECT LOAN/CREDITAND PROJECTSUMMARY Borrower: The People's Republic of China. Beneficiaries: Yunnan Province; the Municipalities of Gejiu, Kunming and Qujing; the water supply companies of Kunming and Qujing; the wastewater companies of Gejiu, Kunming and Qujing; industrial enterprises. Poverty: Not applicable. Amount: Loan: $125 million. Credit: SDR 17.4 million ($25 million -

Yunnan Provincial Highway Bureau

IPP740 REV World Bank-financed Yunnan Highway Assets management Project Public Disclosure Authorized Ethnic Minority Development Plan of the Yunnan Highway Assets Management Project Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Yunnan Provincial Highway Bureau July 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized EMDP of the Yunnan Highway Assets management Project Summary of the EMDP A. Introduction 1. According to the Feasibility Study Report and RF, the Project involves neither land acquisition nor house demolition, and involves temporary land occupation only. This report aims to strengthen the development of ethnic minorities in the project area, and includes mitigation and benefit enhancing measures, and funding sources. The project area involves a number of ethnic minorities, including Yi, Hani and Lisu. B. Socioeconomic profile of ethnic minorities 2. Poverty and income: The Project involves 16 cities/prefectures in Yunnan Province. In 2013, there were 6.61 million poor population in Yunnan Province, which accounting for 17.54% of total population. In 2013, the per capita net income of rural residents in Yunnan Province was 6,141 yuan. 3. Gender Heads of households are usually men, reflecting the superior status of men. Both men and women do farm work, where men usually do more physically demanding farm work, such as fertilization, cultivation, pesticide application, watering, harvesting and transport, while women usually do housework or less physically demanding farm work, such as washing clothes, cooking, taking care of old people and children, feeding livestock, and field management. In Lijiang and Dali, Bai and Naxi women also do physically demanding labor, which is related to ethnic customs. Means of production are usually purchased by men, while daily necessities usually by women. -

The Status and Distribution of Green Peafowl Pavo Muticus in Yunnan Province, China

The status and distribution of green peafowl Pavo muticus in Yunnan Province, China LIANXIAN HAN *, YUEQIANG LIU and BENG HAN Faculty of Conservation Biology, Southwest Forestry College, Kunming Yunnan China 650224. *Correspondence author - [email protected] Paper presented at the 4 th International Galliformes Symposium, 2007, Chengdu, China. Abstract Data on the status and distribution of the green peafowl in Yunnan Province, China, were collected from historical data, field surveys carried out between March and June 2007 around Shuangbai and Baoshan, and from a correspondence survey among city, state and county Forestry Bureaux and Protection Agencies. The data showed that green peafowl occurred historically in at least 42 locations, but by the late 1980s they were already absent from Yingjiang, Tengchong, Liuku, Mengzi and Hekou, and by the late 1990s were also absent from Mengla, Jinping and Luchun and Jianshui County. Green peafowl were found to be present in 31 known areas: Weishan, Yongren, Jinghong, Ruili, Longchuan, Luxi, Longling, Changning, Fengqing, Yunxian, Yongde, Chenkang, Kengma, Cangyuan, Shuangjiang, Lincang, Jingdong, Jinggu, Chenyuan, Pu'er, Simao, Menghai, Mojiang, Shiping, Maitreya, Sinping, Shuangbai, Chuxiong, Lufeng, Nanhua, and Yao'an. Among these, Weishan, Yongren, Jing Hong, Mengla have only supported green peafowl since the latter half of the 1980s. This evaluation also located green peafowl in six new areas, namely Baoshan, Nanjian, Lancang, Yuxi, Shidian and Honghe. It remains unknown if two further -

Save the Children in China 2013 Annual Review

Save the Children in China 2013 Annual Review Save the Children in China 2013 Annual Review i CONTENTS 405,579 In 2013, Save the Children’s child education 02 2013 for Save the Children in China work helped 405,579 children and 206,770 adults in China. 04 With Children and For Children 06 Saving Children’s Lives 08 Education and Development 14 Child Protection 16 Disaster Risk Reduction and Humanitarian Relief 18 Our Voice for Children 1 20 Media and Public Engagement 22 Our Supporters Save the Children organised health and hygiene awareness raising activities in the Nagchu Prefecture of Tibet on October 15th, 2013 – otherwise known as International Handwashing Day. In addition to teaching community members and elementary school students how to wash their hands properly, we distributed 4,400 hygiene products, including washbasins, soap, toothbrushes, toothpastes, nail clippers and towels. 92,150 24 Finances In 2013, we responded to three natural disasters in China, our disaster risk reduction work and emergency response helped 92,150 Save the Children is the world’s leading independent children and 158,306 adults. organisation for children Our vision A world in which every child attains the right to survival, protection, development and 48,843 participation In 2013, our child protection work in China helped 48,843 children and 75,853 adults. Our mission To inspire breakthroughs in the way the world treats children, and to achieve immediate and 2 lasting change in their lives Our values 1 Volunteers cheer on Save the Children’s team at the Beijing Marathon on October 20th 2013.