Olig2 Is Required for Zebrafish Primary Motor Neuron and Oligodendrocyte Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neural Control of Movement: Motor Neuron Subtypes, Proprioception and Recurrent Inhibition

List of Papers This thesis is based on the following papers, which are referred to in the text by their Roman numerals. I Enjin A, Rabe N, Nakanishi ST, Vallstedt A, Gezelius H, Mem- ic F, Lind M, Hjalt T, Tourtellotte WG, Bruder C, Eichele G, Whelan PJ, Kullander K (2010) Identification of novel spinal cholinergic genetic subtypes disclose Chodl and Pitx2 as mark- ers for fast motor neurons and partition cells. J Comp Neurol 518:2284-2304. II Wootz H, Enjin A, Wallen-Mackenzie Å, Lindholm D, Kul- lander K (2010) Reduced VGLUT2 expression increases motor neuron viability in Sod1G93A mice. Neurobiol Dis 37:58-66 III Enjin A, Leao KE, Mikulovic S, Le Merre P, Tourtellotte WG, Kullander K. 5-ht1d marks gamma motor neurons and regulates development of sensorimotor connections Manuscript IV Enjin A, Leao KE, Eriksson A, Larhammar M, Gezelius H, Lamotte d’Incamps B, Nagaraja C, Kullander K. Development of spinal motor circuits in the absence of VIAAT-mediated Renshaw cell signaling Manuscript Reprints were made with permission from the respective publishers. Cover illustration Carousel by Sasha Svensson Contents Introduction.....................................................................................................9 Background...................................................................................................11 Neural control of movement.....................................................................11 The motor neuron.....................................................................................12 Organization -

ALS and Other Motor Neuron Diseases Can Represent Diagnostic Challenges

Review Article Address correspondence to Dr Ezgi Tiryaki, Hennepin ALS and Other Motor County Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 701 Park Avenue P5-200, Neuron Diseases Minneapolis, MN 55415, [email protected]. Ezgi Tiryaki, MD; Holli A. Horak, MD, FAAN Relationship Disclosure: Dr Tiryaki’s institution receives support from The ALS Association. Dr Horak’s ABSTRACT institution receives a grant from the Centers for Disease Purpose of Review: This review describes the most common motor neuron disease, Control and Prevention. ALS. It discusses the diagnosis and evaluation of ALS and the current understanding of its Unlabeled Use of pathophysiology, including new genetic underpinnings of the disease. This article also Products/Investigational covers other motor neuron diseases, reviews how to distinguish them from ALS, and Use Disclosure: Drs Tiryaki and Horak discuss discusses their pathophysiology. the unlabeled use of various Recent Findings: In this article, the spectrum of cognitive involvement in ALS, new concepts drugs for the symptomatic about protein synthesis pathology in the etiology of ALS, and new genetic associations will be management of ALS. * 2014, American Academy covered. This concept has changed over the past 3 to 4 years with the discovery of new of Neurology. genes and genetic processes that may trigger the disease. As of 2014, two-thirds of familial ALS and 10% of sporadic ALS can be explained by genetics. TAR DNA binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43), for instance, has been shown to cause frontotemporal dementia as well as some cases of familial ALS, and is associated with frontotemporal dysfunction in ALS. Summary: The anterior horn cells control all voluntary movement: motor activity, res- piratory, speech, and swallowing functions are dependent upon signals from the anterior horn cells. -

Lancl1 Promotes Motor Neuron Survival and Extends the Lifespan of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Mice

Cell Death & Differentiation (2020) 27:1369–1382 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-019-0422-6 ARTICLE LanCL1 promotes motor neuron survival and extends the lifespan of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Honglin Tan ● Mina Chen ● Dejiang Pang ● Xiaoqiang Xia ● Chongyangzi Du ● Wanchun Yang ● Yiyuan Cui ● 1,2 1 1,3 4 4 3 1,5 Chao Huang ● Wanxiang Jiang ● Dandan Bi ● Chunyu Li ● Huifang Shang ● Paul F. Worley ● Bo Xiao Received: 19 November 2018 / Revised: 3 September 2019 / Accepted: 6 September 2019 / Published online: 30 September 2019 © The Author(s) 2019. This article is published with open access Abstract Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive loss of motor neurons. Improving neuronal survival in ALS remains a significant challenge. Previously, we identified Lanthionine synthetase C-like protein 1 (LanCL1) as a neuronal antioxidant defense gene, the genetic deletion of which causes apoptotic neurodegeneration in the brain. Here, we report in vivo data using the transgenic SOD1G93A mouse model of ALS indicating that CNS-specific expression of LanCL1 transgene extends lifespan, delays disease onset, decelerates symptomatic progression, and improves motor performance of SOD1G93A mice. Conversely, CNS-specific deletion of fl 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: LanCL1 leads to neurodegenerative phenotypes, including motor neuron loss, neuroin ammation, and oxidative damage. Analysis reveals that LanCL1 is a positive regulator of AKT activity, and LanCL1 overexpression restores the impaired AKT activity in ALS model mice. These findings indicate that LanCL1 regulates neuronal survival through an alternative mechanism, and suggest a new therapeutic target in ALS. -

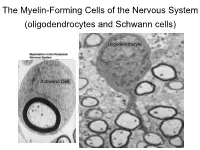

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes -

Cortex Brainstem Spinal Cord Thalamus Cerebellum Basal Ganglia

Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology HST.131: Introduction to Neuroscience Course Director: Dr. David Corey Motor Systems I 1 Emad Eskandar, MD Motor Systems I - Muscles & Spinal Cord Introduction Normal motor function requires the coordination of multiple inter-elated areas of the CNS. Understanding the contributions of these areas to generating movements and the disturbances that arise from their pathology are important challenges for the clinician and the scientist. Despite the importance of diseases that cause disorders of movement, the precise function of many of these areas is not completely clear. The main constituents of the motor system are the cortex, basal ganglia, cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord. Cortex Basal Ganglia Cerebellum Thalamus Brainstem Spinal Cord In very broad terms, cortical motor areas initiate voluntary movements. The cortex projects to the spinal cord directly, through the corticospinal tract - also known as the pyramidal tract, or indirectly through relay areas in the brain stem. The cortical output is modified by two parallel but separate re entrant side loops. One loop involves the basal ganglia while the other loop involves the cerebellum. The final outputs for the entire system are the alpha motor neurons of the spinal cord, also called the Lower Motor Neurons. Cortex: Planning and initiation of voluntary movements and integration of inputs from other brain areas. Basal Ganglia: Enforcement of desired movements and suppression of undesired movements. Cerebellum: Timing and precision of fine movements, adjusting ongoing movements, motor learning of skilled tasks Brain Stem: Control of balance and posture, coordination of head, neck and eye movements, motor outflow of cranial nerves Spinal Cord: Spontaneous reflexes, rhythmic movements, motor outflow to body. -

Motor Neuron Disease Motor Neuron Disease

Motor Neuron Disease Motor Neuron Disease • Incidence: 2-4 per 100 000 • Onset: usually 50-70 years • Pathology: – Degenerative condition – anterior horn cells and upper motor neurons in spinal cord, resulting in mixed upper and lower motor neuron signs • Cause unknown – 10% familial (SOD-1 mutation) – ? Related to athleticism Presentation • Several variations in onset, but progress to the same endpoint • Motor nerves only affected • May be just UMN or just LMN at onset, but other features will appear over time • Main patterns: – Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis – Bulbar presentaion – Primary lateral sclerosis (UMN onset) – Progressive muscular atrophy (LMN onset) Questions Wasting Classification • Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis • Progressive Bulbar Palsy • Progressive Muscular Atrophy • Primary Lateral Sclerosis • Multifocal Motor Neuropathy • Spinal Muscular Atrophy • Kennedy’s Disease • Monomelic Amyotrophy • Brachial Amyotrophic Diplegia El Escorial Criteria for Diagnosis Tongue fasiculations Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis • ‘Typical’ presentation (60%+) • Usually one limb initially – Foot drop – Clumsy weak hand – May complain of cramps • Gradual progression over months • May be some wasting at presentation • Usually fasiculations (often more widespread) • Brisk reflexes, extensor plantars • No sensory signs; MAY occasionally be mild symptoms • Relentless progression, noticable over weeks/ months Bulbar MND • Approximately 30% of cases • Onset with dysarthria, dysphagia • Bulbar and pseudobulbar symptoms • On examination – Dysarthria – -

Olig2 Precursors Produce Abducens Motor Neurons and Oligodendrocytes in the Zebrafish Hindbrain

2322 • The Journal of Neuroscience, February 25, 2009 • 29(8):2322–2333 Cellular/Molecular Olig2ϩ Precursors Produce Abducens Motor Neurons and Oligodendrocytes in the Zebrafish Hindbrain Denise A. Zannino1,2 and Bruce Appel1,3 1Program in Neuroscience and 2Department of Biological Sciences, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee 37235, and 3Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Denver, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado 80045 During development, a specific subset of ventral spinal cord precursors called pMN cells produces first motor neurons and then oligo- dendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs), which migrate, divide and differentiate as myelinating oligodendrocytes. pMN cells express the Olig2 transcription factor and Olig2 function is necessary for formation of spinal motor neurons and OPCs. In the hindbrain and midbrain, distinct classes of visceral, branchiomotor and somatic motor neurons are organized as discrete nuclei, and OPCs are broadly distributed. Mouse embryos deficient for Olig2 function lack somatic motor neurons and OPCs, but it is not clear whether this reflects a common origin for these cells, similar to spinal cord, or independent requirements for Olig2 function in somatic motor neuron and OPC develop- ment. We investigated cranial motor neuron and OPC development in zebrafish and found, using a combination of transgenic reporters and cell type specific antibodies, that somatic abducens motor neurons and a small subset of OPCs arise from common olig2ϩ neuroep- ithelial precursors in rhombomeres r5 and r6, but that all other motor neurons and OPCs do not similarly develop from shared pools of olig2ϩ precursors. In the absence of olig2 function, r5 and r6 precursors remain in the cell cycle and fail to produce abducens motor neurons, and OPCs are entirely lacking in the hindbrain. -

Gamma Motor Neurons Survive and Exacerbate Alpha Motor Neuron Degeneration In

Gamma motor neurons survive and exacerbate alpha PNAS PLUS motor neuron degeneration in ALS Melanie Lalancette-Heberta,b, Aarti Sharmaa,b, Alexander K. Lyashchenkoa,b, and Neil A. Shneidera,b,1 aCenter for Motor Neuron Biology and Disease, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032; and bDepartment of Neurology, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032 Edited by Rob Brownstone, University College London, London, United Kingdom, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Fred H. Gage October 27, 2016 (received for review April 4, 2016) The molecular and cellular basis of selective motor neuron (MN) the muscle spindle and control the sensitivity of spindle afferent vulnerability in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is not known. In discharge (15); beta (β) skeletofusimotor neurons innervate both genetically distinct mouse models of familial ALS expressing intra- and extrafusal muscle (16). In addition to morphological mutant superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD1), TAR DNA-binding protein differences, distinct muscle targets, and the absence of primary 43 (TDP-43), and fused in sarcoma (FUS), we demonstrate selective afferent (IA)inputsonγ-MNs, these functional MN subtypes also degeneration of alpha MNs (α-MNs) and complete sparing of differ in their trophic requirements, and γ-MNs express high levels gamma MNs (γ-MNs), which selectively innervate muscle spindles. of the glial cell line-derived neurotropic factor (GDNF) receptor Resistant γ-MNs are distinct from vulnerable α-MNs in that they Gfrα1 (17). γ-MNs are also molecularly distinguished by the ex- lack synaptic contacts from primary afferent (IA) fibers. Elimination pression of other selective markers including the transcription α of these synapses protects -MNs in the SOD1 mutant, implicating factor Err3 (18), Wnt7A (19), the serotonin receptor 1d (5-ht1d) this excitatory input in MN degeneration. -

Spinal Reflexes

Spinal Reflexes Lu Chen, Ph.D. MCB, UC Berkeley 1 Simple reflexes such as stretch reflex require coordinated contraction and relaxation of different muscle groups Categories of Muscle Based on Direction of Motion Flexors Æ reduce the angle of joints Extensors Æ increase the angle of joints Categories of Muscle Based on Movement Agonist Æmuscle that serves to move the joint in the same direction as the studied muscle Antagonist Æ muscle that moves the joint in the opposite direction 2 1 Muscle Spindles •Small encapsulated sensory receptors that have a Intrafusal muscle spindle-like shape and are located within the fibers fleshy part of the muscle •In parallel with the muscle fibers capsule •Does not contribute to the overall contractile Sensory force endings •Mechanoreceptors are activated by stretch of the central region Afferent axons •Due to stretch of the whole muscle Efferent axons (including intrafusal f.) •Due to contraction of the polar regions of Gamma motor the intrafusal fibers endings 3 Muscle Spindles Organization 2 kinds of intrafusal muscle fibers •Nuclear bag fibers (2-3) •Dynamic •Static •Nuclear chain fibers (~5) •Static 2 types of sensory fibers •Ia (primary) - central region of all intrafusal fibers •II (secondary) - adjacent to the central region of static nuclear bag fibers and nuclear chain fibers Intrafusal fibers stretched Sensory ending stretched, (loading the spindle) increase firing Muscle fibers lengthens Sensory ending stretched, (stretched) increase firing Spindle unloaded, Muscle fiber shortens decrease firing 4 2 Muscle Spindles Organization Gamma motor neurons innervate the intrafusal muscle fibers. Activation of Shortening of the polar regions gamma neurons of the intrafusal fibers Stretches the noncontractile Increase firing of the center regions sensory endings Therefore, the gamma motor neurons provide a mechanism for adjusting the sensitivity of the muscle spindles. -

Oligodendrocyte Dysfunction in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Perspectives

cells Review Oligodendrocyte Dysfunction in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Perspectives Stefano Raffaele , Marta Boccazzi and Marta Fumagalli * Department of Pharmacological and Biomolecular Sciences, Università degli Studi di Milano, 20133 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (S.R.); [email protected] (M.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0250318307 Abstract: Myelin is the lipid-rich structure formed by oligodendrocytes (OLs) that wraps the axons in multilayered sheaths, assuring protection, efficient saltatory signal conduction and metabolic support to neurons. In the last few years, the impact of OL dysfunction and myelin damage has progressively received more attention and is now considered to be a major contributing factor to neurodegeneration in several neurological diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Upon OL injury, oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) of adult nervous tissue sustain the generation of new OLs for myelin reconstitution, but this spontaneous regeneration process fails to successfully counteract myelin damage. Of note, the functions of OPCs exceed the formation and repair of myelin, and also involve the trophic support to axons and the capability to exert an immunomodulatory role, which are particularly relevant in the context of neurodegeneration. In this review, we deeply analyze the impact of dysfunctional OLs in ALS pathogenesis. The possible mechanisms underlying OL degeneration, defective OPC maturation, and impairment in energy supply to motor neurons (MNs) Citation: Raffaele, S.; Boccazzi, M.; have also been examined to provide insights on future therapeutic interventions. On this basis, we Fumagalli, M. Oligodendrocyte discuss the potential therapeutic utility in ALS of several molecules, based on their remyelinating Dysfunction in Amyotrophic Lateral potential or capability to enhance energy metabolism. -

Systematic Elucidation of Neuron-Astrocyte Interaction in Models of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Using Multi-Modal Integrated Bioinformatics Workflow

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19177-y OPEN Systematic elucidation of neuron-astrocyte interaction in models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using multi-modal integrated bioinformatics workflow Vartika Mishra et al.# 1234567890():,; Cell-to-cell communications are critical determinants of pathophysiological phenotypes, but methodologies for their systematic elucidation are lacking. Herein, we propose an approach for the Systematic Elucidation and Assessment of Regulatory Cell-to-cell Interaction Net- works (SEARCHIN) to identify ligand-mediated interactions between distinct cellular com- partments. To test this approach, we selected a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), in which astrocytes expressing mutant superoxide dismutase-1 (mutSOD1) kill wild-type motor neurons (MNs) by an unknown mechanism. Our integrative analysis that combines proteomics and regulatory network analysis infers the interaction between astrocyte-released amyloid precursor protein (APP) and death receptor-6 (DR6) on MNs as the top predicted ligand-receptor pair. The inferred deleterious role of APP and DR6 is confirmed in vitro in models of ALS. Moreover, the DR6 knockdown in MNs of transgenic mutSOD1 mice attenuates the ALS-like phenotype. Our results support the usefulness of integrative, systems biology approach to gain insights into complex neurobiological disease processes as in ALS and posit that the proposed methodology is not restricted to this biological context and could be used in a variety of other non-cell-autonomous communication -

A Mathematical Model of the Neuromuscular Junction and Muscle Force Generation in the Pathological Condition Myasthenia Gravis

A Mathematical Model of the Neuromuscular Junction and Muscle Force Generation in the Pathological Condition Myasthenia Gravis Taylor Meredith Abstract At the neuromuscular junction, motor neurons stimulate muscle fibers to contract through many detailed processes. This paper discusses a model to connect the many processes involved in muscle contraction from the electrical activity of nerve impulses to the mechanical force generation. Through the use of differential equations to describe calcium dynamics and muscle force, coupled to end plate potentials at the neuromuscular junction, we model this process in both a healthy system and a damaged system. As an application of our model, we focus on the neuromuscular disease myasthenia gravis and how it affects muscle force generation in our model, as well as the effect of acetylcholinesterase inhibiting treatment. 1 Introduction Figure 1: The neuromuscular junction. Our goal is to design a mathematical model that bridges the gap between the electrical activity of neurons and the mechanical action of muscle contraction. This so-called \gap" is known as the neuromuscular junction (Figure 1), an important biological feature in humans, as well as other animals, that allows for the transmission of signals from a motor neuron to a muscle fiber [7]. The motor neuron axon is a long projection of the motor neuron that conducts electrical 1 impulses known as action potentials. At every muscle fiber a neuromuscular junction exists, where the motor neuron axon releases synaptic vesicles, each containing a `quantum' of the neurotransmitter. In mammals, the neurotransmitter is acetylcholine and each `quantum' contains approximately 10,000 molecules of acetylcholine [6].