Neural Control of Movement: Motor Neuron Subtypes, Proprioception and Recurrent Inhibition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Degeneration of Cells Surrounding Motoneurons Contributes to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

cells Review How Degeneration of Cells Surrounding Motoneurons Contributes to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Roxane Crabé 1, Franck Aimond 1, Philippe Gosset 1 , Frédérique Scamps 1 and Cédric Raoul 1,2,* 1 The Neuroscience Institute of Montpellier, INSERM, UMR1051, University of Montpellier, 34091 Montpellier, France; [email protected] (R.C.); [email protected] (F.A.); [email protected] (P.G.); [email protected] (F.S.) 2 Laboratory of Neurobiology, Kazan Federal University, 420008 Kazan, Russia * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 October 2020; Accepted: 24 November 2020; Published: 27 November 2020 Abstract: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurological disorder characterized by the progressive degeneration of upper and lower motoneurons. Despite motoneuron death being recognized as the cardinal event of the disease, the loss of glial cells and interneurons in the brain and spinal cord accompanies and even precedes motoneuron elimination. In this review, we provide striking evidence that the degeneration of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, in addition to inhibitory and modulatory interneurons, disrupt the functionally coherent environment of motoneurons. We discuss the extent to which the degeneration of glial cells and interneurons also contributes to the decline of the motor system. This pathogenic cellular network therefore represents a novel strategic field of therapeutic investigation. Keywords: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; spinal cord; cortex; motoneuron; astrocytes; interneuron; oligodendrocytes; degeneration 1. Introduction Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is an adult-onset neurodegenerative disease characterized by the selective and progressive loss of upper and lower motoneurons. ALS begins with focal muscle weakness and wasting that relentlessly spreads to other body parts, leading to death mostly from respiratory failure within three years of onset. -

Speed and Segmentation Control Mechanisms Characterized in Rhythmically- Active Circuits Created from Spinal Neurons Produced Fr

RESEARCH ARTICLE Speed and segmentation control mechanisms characterized in rhythmically- active circuits created from spinal neurons produced from genetically-tagged embryonic stem cells Matthew J Sternfeld1,2, Christopher A Hinckley1, Niall J Moore1, Matthew T Pankratz1, Kathryn L Hilde1,3, Shawn P Driscoll1, Marito Hayashi1,2, Neal D Amin1,3,4, Dario Bonanomi1†, Wesley D Gifford1,4,5, Kamal Sharma6, Martyn Goulding7, Samuel L Pfaff1* 1Gene Expression Laboratory, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, United States; 2Biological Sciences Graduate Program, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, United States; 3Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, United States; 4Medical Scientist Training Program, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, United States; 5Neurosciences Graduate Program, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, United States; 6Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, United States; 7Molecular Neurobiology Laboratory, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, United States *For correspondence: pfaff@salk. edu Abstract Flexible neural networks, such as the interconnected spinal neurons that control Present address: †Division of distinct motor actions, can switch their activity to produce different behaviors. Both excitatory (E) Neuroscience, San Raffaele and inhibitory (I) spinal neurons are necessary for motor behavior, but the influence of recruiting Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy different ratios of E-to-I cells remains unclear. We constructed synthetic microphysical neural networks, called circuitoids, using precise combinations of spinal neuron subtypes derived from Competing interests: The mouse stem cells. Circuitoids of purified excitatory interneurons were sufficient to generate authors declare that no oscillatory bursts with properties similar to in vivo central pattern generators. -

Deconstructing Spinal Interneurons, One Cell Type at a Time Mariano Ignacio Gabitto

Deconstructing spinal interneurons, one cell type at a time Mariano Ignacio Gabitto Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Mariano Ignacio Gabitto All rights reserved ABSTRACT Deconstructing spinal interneurons, one cell type at a time Mariano Ignacio Gabitto Abstract Documenting the extent of cellular diversity is a critical step in defining the functional organization of the nervous system. In this context, we sought to develop statistical methods capable of revealing underlying cellular diversity given incomplete data sampling - a common problem in biological systems, where complete descriptions of cellular characteristics are rarely available. We devised a sparse Bayesian framework that infers cell type diversity from partial or incomplete transcription factor expression data. This framework appropriately handles estimation uncertainty, can incorporate multiple cellular characteristics, and can be used to optimize experimental design. We applied this framework to characterize a cardinal inhibitory population in the spinal cord. Animals generate movement by engaging spinal circuits that direct precise sequences of muscle contraction, but the identity and organizational logic of local interneurons that lie at the core of these circuits remain unresolved. By using our Sparse Bayesian approach, we showed that V1 interneurons, a major inhibitory population that controls motor output, fractionate into diverse subsets on the basis of the expression of nineteen transcription factors. Transcriptionally defined subsets exhibit highly structured spatial distributions with mediolateral and dorsoventral positional biases. These distinctions in settling position are largely predictive of patterns of input from sensory and motor neurons, arguing that settling position is a determinant of inhibitory microcircuit organization. -

ALS and Other Motor Neuron Diseases Can Represent Diagnostic Challenges

Review Article Address correspondence to Dr Ezgi Tiryaki, Hennepin ALS and Other Motor County Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 701 Park Avenue P5-200, Neuron Diseases Minneapolis, MN 55415, [email protected]. Ezgi Tiryaki, MD; Holli A. Horak, MD, FAAN Relationship Disclosure: Dr Tiryaki’s institution receives support from The ALS Association. Dr Horak’s ABSTRACT institution receives a grant from the Centers for Disease Purpose of Review: This review describes the most common motor neuron disease, Control and Prevention. ALS. It discusses the diagnosis and evaluation of ALS and the current understanding of its Unlabeled Use of pathophysiology, including new genetic underpinnings of the disease. This article also Products/Investigational covers other motor neuron diseases, reviews how to distinguish them from ALS, and Use Disclosure: Drs Tiryaki and Horak discuss discusses their pathophysiology. the unlabeled use of various Recent Findings: In this article, the spectrum of cognitive involvement in ALS, new concepts drugs for the symptomatic about protein synthesis pathology in the etiology of ALS, and new genetic associations will be management of ALS. * 2014, American Academy covered. This concept has changed over the past 3 to 4 years with the discovery of new of Neurology. genes and genetic processes that may trigger the disease. As of 2014, two-thirds of familial ALS and 10% of sporadic ALS can be explained by genetics. TAR DNA binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43), for instance, has been shown to cause frontotemporal dementia as well as some cases of familial ALS, and is associated with frontotemporal dysfunction in ALS. Summary: The anterior horn cells control all voluntary movement: motor activity, res- piratory, speech, and swallowing functions are dependent upon signals from the anterior horn cells. -

Innovations Present in the Primate Interneuron Repertoire

Article Innovations present in the primate interneuron repertoire https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2781-z Fenna M. Krienen1,2 ✉, Melissa Goldman1,2, Qiangge Zhang2,3, Ricardo C. H. del Rosario2, Marta Florio1,2, Robert Machold4, Arpiar Saunders1,2, Kirsten Levandowski2,3, Heather Zaniewski2,3, Received: 19 July 2019 Benjamin Schuman4, Carolyn Wu3, Alyssa Lutservitz1,2, Christopher D. Mullally1,2, Nora Reed1,2, Accepted: 1 July 2020 Elizabeth Bien1,2, Laura Bortolin1,2, Marian Fernandez-Otero2,5, Jessica D. Lin2, Alec Wysoker2, James Nemesh2, David Kulp2, Monika Burns5, Victor Tkachev6,7,8, Richard Smith9,10, Published online: xx xx xxxx Christopher A. Walsh9,10, Jordane Dimidschstein2, Bernardo Rudy4,11, Leslie S. Kean6,7,8, Check for updates Sabina Berretta5,12,13, Gord Fishell2,14, Guoping Feng2,3 & Steven A. McCarroll1,2 ✉ Primates and rodents, which descended from a common ancestor around 90 million years ago1, exhibit profound diferences in behaviour and cognitive capacity; the cellular basis for these diferences is unknown. Here we use single-nucleus RNA sequencing to profle RNA expression in 188,776 individual interneurons across homologous brain regions from three primates (human, macaque and marmoset), a rodent (mouse) and a weasel (ferret). Homologous interneuron types—which were readily identifed by their RNA-expression patterns—varied in abundance and RNA expression among ferrets, mice and primates, but varied less among primates. Only a modest fraction of the genes identifed as ‘markers’ of specifc interneuron subtypes in any one species had this property in another species. In the primate neocortex, dozens of genes showed spatial expression gradients among interneurons of the same type, which suggests that regional variation in cortical contexts shapes the RNA expression patterns of adult neocortical interneurons. -

Spinal Cord Organization

Lecture 4 Spinal Cord Organization The spinal cord . Afferent tract • connects with spinal nerves, through afferent BRAIN neuron & efferent axons in spinal roots; reflex receptor interneuron • communicates with the brain, by means of cell ascending and descending pathways that body form tracts in spinal white matter; and white matter muscle • gives rise to spinal reflexes, pre-determined gray matter Efferent neuron by interneuronal circuits. Spinal Cord Section Gross anatomy of the spinal cord: The spinal cord is a cylinder of CNS. The spinal cord exhibits subtle cervical and lumbar (lumbosacral) enlargements produced by extra neurons in segments that innervate limbs. The region of spinal cord caudal to the lumbar enlargement is conus medullaris. Caudal to this, a terminal filament of (nonfunctional) glial tissue extends into the tail. terminal filament lumbar enlargement conus medullaris cervical enlargement A spinal cord segment = a portion of spinal cord that spinal ganglion gives rise to a pair (right & left) of spinal nerves. Each spinal dorsal nerve is attached to the spinal cord by means of dorsal and spinal ventral roots composed of rootlets. Spinal segments, spinal root (rootlets) nerve roots, and spinal nerves are all identified numerically by th region, e.g., 6 cervical (C6) spinal segment. ventral Sacral and caudal spinal roots (surrounding the conus root medullaris and terminal filament and streaming caudally to (rootlets) reach corresponding intervertebral foramina) collectively constitute the cauda equina. Both the spinal cord (CNS) and spinal roots (PNS) are enveloped by meninges within the vertebral canal. Spinal nerves (which are formed in intervertebral foramina) are covered by connective tissue (epineurium, perineurium, & endoneurium) rather than meninges. -

Are Astrocytes Executive Cells Within the Central Nervous System? ¿Son Los Astrocitos Células Ejecutivas Dentro Del Sistema Nervioso Central? Roberto E

DOI: 10.1590/0004-282X20160101 VIEW AND REVIEW Are astrocytes executive cells within the central nervous system? ¿Son los astrocitos células ejecutivas dentro del Sistema Nervioso Central? Roberto E. Sica1, Roberto Caccuri1, Cecilia Quarracino1, Francisco Capani1 ABSTRACT Experimental evidence suggests that astrocytes play a crucial role in the physiology of the central nervous system (CNS) by modulating synaptic activity and plasticity. Based on what is currently known we postulate that astrocytes are fundamental, along with neurons, for the information processing that takes place within the CNS. On the other hand, experimental findings and human observations signal that some of the primary degenerative diseases of the CNS, like frontotemporal dementia, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s dementia, Huntington’s dementia, primary cerebellar ataxias and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, all of which affect the human species exclusively, may be due to astroglial dysfunction. This hypothesis is supported by observations that demonstrated that the killing of neurons by non-neural cells plays a major role in the pathogenesis of those diseases, at both their onset and their progression. Furthermore, recent findings suggest that astrocytes might be involved in the pathogenesis of some psychiatric disorders as well. Keywords: astrocytes; physiology; central nervous system; neurodegenerative diseases. RESUMEN Evidencias experimentales sugieren que los astrocitos desempeñan un rol crucial en la fisiología del sistema nervioso central (SNC) modulando la actividad y plasticidad sináptica. En base a lo actualmente conocido creemos que los astrocitos participan, en pie de igualdad con las neuronas, en los procesos de información del SNC. Además, observaciones experimentales y humanas encontraron que algunas de las enfermedades degenerativas primarias del SNC: la demencia fronto-temporal; las enfermedades de Parkinson, de Alzheimer, y de Huntington, las ataxias cerebelosas primarias y la esclerosis lateral amiotrófica, que afectan solo a los humanos, pueden deberse a astroglíopatía. -

Lancl1 Promotes Motor Neuron Survival and Extends the Lifespan of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Mice

Cell Death & Differentiation (2020) 27:1369–1382 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-019-0422-6 ARTICLE LanCL1 promotes motor neuron survival and extends the lifespan of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Honglin Tan ● Mina Chen ● Dejiang Pang ● Xiaoqiang Xia ● Chongyangzi Du ● Wanchun Yang ● Yiyuan Cui ● 1,2 1 1,3 4 4 3 1,5 Chao Huang ● Wanxiang Jiang ● Dandan Bi ● Chunyu Li ● Huifang Shang ● Paul F. Worley ● Bo Xiao Received: 19 November 2018 / Revised: 3 September 2019 / Accepted: 6 September 2019 / Published online: 30 September 2019 © The Author(s) 2019. This article is published with open access Abstract Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive loss of motor neurons. Improving neuronal survival in ALS remains a significant challenge. Previously, we identified Lanthionine synthetase C-like protein 1 (LanCL1) as a neuronal antioxidant defense gene, the genetic deletion of which causes apoptotic neurodegeneration in the brain. Here, we report in vivo data using the transgenic SOD1G93A mouse model of ALS indicating that CNS-specific expression of LanCL1 transgene extends lifespan, delays disease onset, decelerates symptomatic progression, and improves motor performance of SOD1G93A mice. Conversely, CNS-specific deletion of fl 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: LanCL1 leads to neurodegenerative phenotypes, including motor neuron loss, neuroin ammation, and oxidative damage. Analysis reveals that LanCL1 is a positive regulator of AKT activity, and LanCL1 overexpression restores the impaired AKT activity in ALS model mice. These findings indicate that LanCL1 regulates neuronal survival through an alternative mechanism, and suggest a new therapeutic target in ALS. -

GDE2 Regulates Subtype-Specific Motor Neuron Generation Through

Neuron Article GDE2 Regulates Subtype-Specific Motor Neuron Generation through Inhibition of Notch Signaling Priyanka Sabharwal,1 Changhee Lee,1 Sungjin Park,1 Meenakshi Rao,1,2 and Shanthini Sockanathan1,* 1The Solomon Snyder Department of Neuroscience, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, PCTB1004, 725 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA 2Present address: Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital Boston, 300 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA *Correspondence: [email protected] DOI 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.028 SUMMARY which is innervated by specific groups of motor neurons. Indi- vidual motor neuron groups are highly organized in terms of their The specification of spinal interneuron and motor cell body distribution, projection patterns, and function and neuron identities initiates within progenitor cells, consist of force-generating alpha motor neurons that innervate while motor neuron subtype diversification is regu- extrafusal muscle fibers and stretch-sensitive gamma motor lated by hierarchical transcriptional programs imple- neurons that innervate intrafusal muscle fibers of the muscle mented postmitotically. Here we find that mice lack- spindles (Dasen and Jessell, 2009; reviewed in Kanning et al., ing GDE2, a six-transmembrane protein that triggers 2010). The integration of input from both alpha and gamma motor neurons is essential for coordinated motor movement to motor neuron generation, exhibit selective losses occur (Kanning et al., 2010). of distinct motor neuron subtypes, specifically in How is diversity engendered in developing motor neurons? defined subsets of limb-innervating motor pools All motor neurons initially derive from ventral progenitor cells that correlate with the loss of force-generating alpha that are specified to become Olig2+ motor neuron progenitors motor neurons. -

1. 2. A) Explain the Compositions of White Matter and Gray

Tfy-99.2710 Introduction to the Structure and Operation of the Human Brain, fall 2015 Exercise 1 1. 2. a) Explain the compositions of white matter and gray matter. White matter consists of glial cells and myelinated axons. It does not contain the cell bodies of neurons and acts as a signal pathway for the gray matter regions of the central nervous system. Gray matter consists of glial cells and unmyelinated axons. It contains neuronal cell bodies. b) Explain shortly the structure of a neuron. Neurons can be divided into three main parts: the cell body or the soma, the dendrites and the axon. The dendrites act as neuronal antennas in that they receive incoming signals. The cell body functions as the information processing unit of the neuron, and is responsible for sending signals forward. The axon is the signal pathway of the neuron; the signals sent by the cell body are transmitted along the axon to the axon terminals located away from the cell body. Signal transfer is along the axon is aided by the myelin sheath that covers the axon. c) Explain: Tfy-99.2710 Introduction to the Structure and Operation of the Human Brain, fall 2015 Exercise 1 i) myelin Membrane that wraps around axons. Formed from glial support cells: oligodendrogolia in the central nervous system and Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system. Myelin facilitates signal transfer along axons by allowing action potentials to skip between the nodes of Ranvier (saltatory conduction). ii) receptor Molecule specialized in receiving a chemical signal by binding a specific neurotransmitter. -

Reduction of Ephrin-A5 Aggravates Disease Progression in Amyotrophic

Rué et al. Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2019) 7:114 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-019-0759-6 RESEARCH Open Access Reduction of ephrin-A5 aggravates disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Laura Rué1,2 , Patrick Oeckl3, Mieke Timmers1,2, Annette Lenaerts1,2, Jasmijn van der Vos1,2, Silke Smolders1,2, Lindsay Poppe1,2, Antina de Boer1,2, Ludo Van Den Bosch1,2, Philip Van Damme1,2,4, Jochen H. Weishaupt3, Albert C. Ludolph3, Markus Otto3, Wim Robberecht1,4 and Robin Lemmens1,2,4* Abstract Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease that affects motor neurons in the brainstem, spinal cord and motor cortex. ALS is characterized by genetic and clinical heterogeneity, suggesting the existence of genetic factors that modify the phenotypic expression of the disease. We previously identified the axonal guidance EphA4 receptor, member of the Eph-ephrin system, as an ALS disease-modifying factor. EphA4 genetic inhibition rescued the motor neuron phenotype in zebrafish and a rodent model of ALS. Preventing ligands from binding to the EphA4 receptor also successfully improved disease, suggesting a role for EphA4 ligands in ALS. One particular ligand, ephrin-A5, is upregulated in reactive astrocytes after acute neuronal injury and inhibits axonal regeneration. Moreover, it plays a role during development in the correct pathfinding of motor axons towards their target limb muscles. We hypothesized that a constitutive reduction of ephrin-A5 signalling would benefit disease progression in a rodent model for ALS. We discovered that in the spinal cord of control and symptomatic ALS mice ephrin-A5 was predominantly expressed in neurons. -

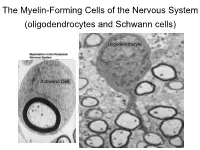

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes