Intersegmental Interneurons Can Control the Gain of Reflexes in Adjacent Segments of the Locust by Their Action on Nonspiking Local Interneurons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neural Control of Movement: Motor Neuron Subtypes, Proprioception and Recurrent Inhibition

List of Papers This thesis is based on the following papers, which are referred to in the text by their Roman numerals. I Enjin A, Rabe N, Nakanishi ST, Vallstedt A, Gezelius H, Mem- ic F, Lind M, Hjalt T, Tourtellotte WG, Bruder C, Eichele G, Whelan PJ, Kullander K (2010) Identification of novel spinal cholinergic genetic subtypes disclose Chodl and Pitx2 as mark- ers for fast motor neurons and partition cells. J Comp Neurol 518:2284-2304. II Wootz H, Enjin A, Wallen-Mackenzie Å, Lindholm D, Kul- lander K (2010) Reduced VGLUT2 expression increases motor neuron viability in Sod1G93A mice. Neurobiol Dis 37:58-66 III Enjin A, Leao KE, Mikulovic S, Le Merre P, Tourtellotte WG, Kullander K. 5-ht1d marks gamma motor neurons and regulates development of sensorimotor connections Manuscript IV Enjin A, Leao KE, Eriksson A, Larhammar M, Gezelius H, Lamotte d’Incamps B, Nagaraja C, Kullander K. Development of spinal motor circuits in the absence of VIAAT-mediated Renshaw cell signaling Manuscript Reprints were made with permission from the respective publishers. Cover illustration Carousel by Sasha Svensson Contents Introduction.....................................................................................................9 Background...................................................................................................11 Neural control of movement.....................................................................11 The motor neuron.....................................................................................12 Organization -

Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond

cells Review Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond Sarah Kuhn y, Laura Gritti y, Daniel Crooks and Yvonne Dombrowski * Wellcome-Wolfson Institute for Experimental Medicine, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT9 7BL, UK; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (L.G.); [email protected] (D.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +0044-28-9097-6127 These authors contributed equally. y Received: 15 October 2019; Accepted: 7 November 2019; Published: 12 November 2019 Abstract: Oligodendrocytes are the myelinating cells of the central nervous system (CNS) that are generated from oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPC). OPC are distributed throughout the CNS and represent a pool of migratory and proliferative adult progenitor cells that can differentiate into oligodendrocytes. The central function of oligodendrocytes is to generate myelin, which is an extended membrane from the cell that wraps tightly around axons. Due to this energy consuming process and the associated high metabolic turnover oligodendrocytes are vulnerable to cytotoxic and excitotoxic factors. Oligodendrocyte pathology is therefore evident in a range of disorders including multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease. Deceased oligodendrocytes can be replenished from the adult OPC pool and lost myelin can be regenerated during remyelination, which can prevent axonal degeneration and can restore function. Cell population studies have recently identified novel immunomodulatory functions of oligodendrocytes, the implications of which, e.g., for diseases with primary oligodendrocyte pathology, are not yet clear. Here, we review the journey of oligodendrocytes from the embryonic stage to their role in homeostasis and their fate in disease. We will also discuss the most common models used to study oligodendrocytes and describe newly discovered functions of oligodendrocytes. -

Build a Neuron

Build a Neuron Objectives: 1. To understand what a neuron is and what it does 2. To understand the anatomy of a neuron in relation to function This activity is great for ALL ages-even college students!! Materials: pipe cleaners (2 full size, 1 cut into 3 for each student) pony beads (6/student Introduction: Little kids: ask them where their brain is (I point to my head and torso areas till they shake their head yes) Talk about legos being the building blocks for a tower and relate that to neurons being the building blocks for your brain and that neurons send messages to other parts of your brain and to and from all your body parts. Give examples: touch from body to brain, movement from brain to body. Neurons are the building blocks of the brain that send and receive messages. Neurons come in all different shapes. Experiment: 1. First build soma by twisting a pipe cleaner into a circle 2. Then put a 2nd pipe cleaner through the circle and bend it over and twist the two strands together to make it look like a lollipop (axon) 3. take 3 shorter pipe cleaners attach to cell body to make dendrites 4. add 6 beads on the axon making sure there is space between beads for the electricity to “jump” between them to send the signal super fast. (myelin sheath) 5. Twist the end of the axon to make it look like 2 feet for the axon terminal. 6. Make a brain by having all of the neurons “talk” to each other (have each student hold their neuron because they’ll just throw them on a table for you to do it.) messages come in through the dendrites and if its a strong enough electrical change, then the cell body sends the Build a Neuron message down it’s axon where a neurotransmitter is released. -

Innovations Present in the Primate Interneuron Repertoire

Article Innovations present in the primate interneuron repertoire https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2781-z Fenna M. Krienen1,2 ✉, Melissa Goldman1,2, Qiangge Zhang2,3, Ricardo C. H. del Rosario2, Marta Florio1,2, Robert Machold4, Arpiar Saunders1,2, Kirsten Levandowski2,3, Heather Zaniewski2,3, Received: 19 July 2019 Benjamin Schuman4, Carolyn Wu3, Alyssa Lutservitz1,2, Christopher D. Mullally1,2, Nora Reed1,2, Accepted: 1 July 2020 Elizabeth Bien1,2, Laura Bortolin1,2, Marian Fernandez-Otero2,5, Jessica D. Lin2, Alec Wysoker2, James Nemesh2, David Kulp2, Monika Burns5, Victor Tkachev6,7,8, Richard Smith9,10, Published online: xx xx xxxx Christopher A. Walsh9,10, Jordane Dimidschstein2, Bernardo Rudy4,11, Leslie S. Kean6,7,8, Check for updates Sabina Berretta5,12,13, Gord Fishell2,14, Guoping Feng2,3 & Steven A. McCarroll1,2 ✉ Primates and rodents, which descended from a common ancestor around 90 million years ago1, exhibit profound diferences in behaviour and cognitive capacity; the cellular basis for these diferences is unknown. Here we use single-nucleus RNA sequencing to profle RNA expression in 188,776 individual interneurons across homologous brain regions from three primates (human, macaque and marmoset), a rodent (mouse) and a weasel (ferret). Homologous interneuron types—which were readily identifed by their RNA-expression patterns—varied in abundance and RNA expression among ferrets, mice and primates, but varied less among primates. Only a modest fraction of the genes identifed as ‘markers’ of specifc interneuron subtypes in any one species had this property in another species. In the primate neocortex, dozens of genes showed spatial expression gradients among interneurons of the same type, which suggests that regional variation in cortical contexts shapes the RNA expression patterns of adult neocortical interneurons. -

Spinal Cord Organization

Lecture 4 Spinal Cord Organization The spinal cord . Afferent tract • connects with spinal nerves, through afferent BRAIN neuron & efferent axons in spinal roots; reflex receptor interneuron • communicates with the brain, by means of cell ascending and descending pathways that body form tracts in spinal white matter; and white matter muscle • gives rise to spinal reflexes, pre-determined gray matter Efferent neuron by interneuronal circuits. Spinal Cord Section Gross anatomy of the spinal cord: The spinal cord is a cylinder of CNS. The spinal cord exhibits subtle cervical and lumbar (lumbosacral) enlargements produced by extra neurons in segments that innervate limbs. The region of spinal cord caudal to the lumbar enlargement is conus medullaris. Caudal to this, a terminal filament of (nonfunctional) glial tissue extends into the tail. terminal filament lumbar enlargement conus medullaris cervical enlargement A spinal cord segment = a portion of spinal cord that spinal ganglion gives rise to a pair (right & left) of spinal nerves. Each spinal dorsal nerve is attached to the spinal cord by means of dorsal and spinal ventral roots composed of rootlets. Spinal segments, spinal root (rootlets) nerve roots, and spinal nerves are all identified numerically by th region, e.g., 6 cervical (C6) spinal segment. ventral Sacral and caudal spinal roots (surrounding the conus root medullaris and terminal filament and streaming caudally to (rootlets) reach corresponding intervertebral foramina) collectively constitute the cauda equina. Both the spinal cord (CNS) and spinal roots (PNS) are enveloped by meninges within the vertebral canal. Spinal nerves (which are formed in intervertebral foramina) are covered by connective tissue (epineurium, perineurium, & endoneurium) rather than meninges. -

Neurons – Is a Basic Cell of the Nervous System. • Neurons Carry Nerve Messages, Or Impulses, from One Part of the Body to Another

Nervous System Nerves and Nerve Cells: Neurons – is a basic cell of the nervous system. • Neurons carry nerve messages, or impulses, from one part of the body to another. Structure of a Nerve Cell: A neuron has three basic parts: 1. Body – controls the cell’s growth 2. Axon – is a long thin fiber that carries impulses away from the cell body Myelin – is a fatty material that insulates the axon and increases the speed at which an impulse travels 3. Dendrites – are short, branching fibers that carry nerve impulses toward the cell body. • A nerve impulse begins when the dendrites are stimulated. The impulse travels along the dendrites to the cell body, and then away from the cell body on the axon. • The impulse must cross a synapse to a muscle or another neuron. Synapse – is the space between an axon and the structure with which the neuron communicates. Types of Nerve Cells: Sensory Neurons – pick up information about your external and internal environment from your sense organs and your body Motor Neurons – sends impulses to your muscles and glands, causing them to react Interneurons – are located only in the brain and spinal cord, pass impulses from one neuron to another The Central Nervous System: • The nervous system consists of two parts. Your brain and spinal cord make up one part, which is called the central nervous system. 1 • The peripheral nervous system, which is the other part, is made up of all the nerves that connect the brain and spinal cord to other parts of the body. The Brain: Brain ± a moist, spongy organ weighing about three pounds is made up of billions of neurons that control almost everything you do and experience. -

1. 2. A) Explain the Compositions of White Matter and Gray

Tfy-99.2710 Introduction to the Structure and Operation of the Human Brain, fall 2015 Exercise 1 1. 2. a) Explain the compositions of white matter and gray matter. White matter consists of glial cells and myelinated axons. It does not contain the cell bodies of neurons and acts as a signal pathway for the gray matter regions of the central nervous system. Gray matter consists of glial cells and unmyelinated axons. It contains neuronal cell bodies. b) Explain shortly the structure of a neuron. Neurons can be divided into three main parts: the cell body or the soma, the dendrites and the axon. The dendrites act as neuronal antennas in that they receive incoming signals. The cell body functions as the information processing unit of the neuron, and is responsible for sending signals forward. The axon is the signal pathway of the neuron; the signals sent by the cell body are transmitted along the axon to the axon terminals located away from the cell body. Signal transfer is along the axon is aided by the myelin sheath that covers the axon. c) Explain: Tfy-99.2710 Introduction to the Structure and Operation of the Human Brain, fall 2015 Exercise 1 i) myelin Membrane that wraps around axons. Formed from glial support cells: oligodendrogolia in the central nervous system and Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system. Myelin facilitates signal transfer along axons by allowing action potentials to skip between the nodes of Ranvier (saltatory conduction). ii) receptor Molecule specialized in receiving a chemical signal by binding a specific neurotransmitter. -

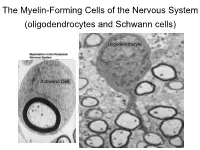

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes -

Cortex Brainstem Spinal Cord Thalamus Cerebellum Basal Ganglia

Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology HST.131: Introduction to Neuroscience Course Director: Dr. David Corey Motor Systems I 1 Emad Eskandar, MD Motor Systems I - Muscles & Spinal Cord Introduction Normal motor function requires the coordination of multiple inter-elated areas of the CNS. Understanding the contributions of these areas to generating movements and the disturbances that arise from their pathology are important challenges for the clinician and the scientist. Despite the importance of diseases that cause disorders of movement, the precise function of many of these areas is not completely clear. The main constituents of the motor system are the cortex, basal ganglia, cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord. Cortex Basal Ganglia Cerebellum Thalamus Brainstem Spinal Cord In very broad terms, cortical motor areas initiate voluntary movements. The cortex projects to the spinal cord directly, through the corticospinal tract - also known as the pyramidal tract, or indirectly through relay areas in the brain stem. The cortical output is modified by two parallel but separate re entrant side loops. One loop involves the basal ganglia while the other loop involves the cerebellum. The final outputs for the entire system are the alpha motor neurons of the spinal cord, also called the Lower Motor Neurons. Cortex: Planning and initiation of voluntary movements and integration of inputs from other brain areas. Basal Ganglia: Enforcement of desired movements and suppression of undesired movements. Cerebellum: Timing and precision of fine movements, adjusting ongoing movements, motor learning of skilled tasks Brain Stem: Control of balance and posture, coordination of head, neck and eye movements, motor outflow of cranial nerves Spinal Cord: Spontaneous reflexes, rhythmic movements, motor outflow to body. -

11 Introduction to the Nervous System and Nervous Tissue

11 Introduction to the Nervous System and Nervous Tissue ou can’t turn on the television or radio, much less go online, without seeing some- 11.1 Overview of the Nervous thing to remind you of the nervous system. From advertisements for medications System 381 Yto treat depression and other psychiatric conditions to stories about celebrities and 11.2 Nervous Tissue 384 their battles with illegal drugs, information about the nervous system is everywhere in 11.3 Electrophysiology our popular culture. And there is good reason for this—the nervous system controls our of Neurons 393 perception and experience of the world. In addition, it directs voluntary movement, and 11.4 Neuronal Synapses 406 is the seat of our consciousness, personality, and learning and memory. Along with the 11.5 Neurotransmitters 413 endocrine system, the nervous system regulates many aspects of homeostasis, including 11.6 Functional Groups respiratory rate, blood pressure, body temperature, the sleep/wake cycle, and blood pH. of Neurons 417 In this chapter we introduce the multitasking nervous system and its basic functions and divisions. We then examine the structure and physiology of the main tissue of the nervous system: nervous tissue. As you read, notice that many of the same principles you discovered in the muscle tissue chapter (see Chapter 10) apply here as well. MODULE 11.1 Overview of the Nervous System Learning Outcomes 1. Describe the major functions of the nervous system. 2. Describe the structures and basic functions of each organ of the central and peripheral nervous systems. 3. Explain the major differences between the two functional divisions of the peripheral nervous system. -

How Does the Brain Work? Grades 9-12

Fact Sheet For Grades 9-12 When a neuron is at rest, the cell body, or How does the soma, of the neuron is negatively charged relative to the outside of the neuron. A neuron at rest has a brain work? negative charge of approximately -70 millivolts By Elizabeth A. Weaver II and Hillary H. Doyle (mV) of electricity. However, when a stimulus comes along (like stubbing your toe, or hearing your name being called), it causes the neuron to With 80-100 billion nerve cells, known as take in more positive ions, and the neuron neurons, the human brain is capable of some becomes more positively charged. Once the astonishing feats. Each neuron is connected to neuron reaches a certain threshold of more than 1,000 other neurons, making the total approximately -55mV, an event known as an action number of connections in the brain around 60 potential occurs and causes the neuron to “fire”. trillion! Neurons are organized into patterns and The action potential travels down the axon where networks within the brain and communicate with it reaches the axon terminal. each other at incredible speeds. At the axon terminal, electrical signals are Each neuron is made up of three main converted into chemical signals that travel parts: the cell body (also known as the soma), the between neurons across a small gap called the axon, and the dendrites. Neurons communicate synapse. These chemicals are called with each other using electrochemical signals. In neurotransmitters. Neurotransmitters cross the other words, certain chemicals in the body known synapse and attach to receptors on the dendrites as ions have an electrical charge. -

Neuron-Satellite Glial Cell Interactions in Sympathetic Nervous System Development

NEURON-SATELLITE GLIAL CELL INTERACTIONS IN SYMPATHETIC NERVOUS SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT by Erica D. Boehm A dissertation submitted to the Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland July 2020 © 2020 Erica Boehm All rights reserved. ABSTRACT Glial cells play crucial roles in maintaining the stability and structure of the nervous system. Satellite glial cells are a loosely defined population of glial cells that ensheathe neuronal cell bodies, dendrites, and synapses of the peripheral nervous system (Elfvin and Forsman 1978; Pannese 1981). Satellite glial cells are closely juxtaposed to peripheral neurons with only 20nm of space between their membranes (Dixon 1969). This close association suggests a tight coupling between the cells to allow for possible exchange of important nutrients, yet very little is known about satellite glial cell function and development. How neurons and glial cells co-develop to create this tightly knit unit remains undefined, as well as the functional consequences of disrupting these contacts. Satellite glial cells are derived from the same population of cells that give rise to peripheral neurons, but do not begin differentiation and proliferation until neurogenesis has been completed (Hall and Landis 1992). A key signaling pathway involved in glial specification is the Delta/Notch signaling pathway (Tsarovina et al. 2008). However, recent studies also implicate Notch signaling in the maturation of glia through non- canonical Notch ligands such as Delta/Notch-like EGF-related Receptor (DNER) (Eiraku et al. 2005). Interestingly, it has been reported that levels of DNER in sympathetic neurons may be dependent on the target-derived growth factor, nerve growth factor (NGF), and this signal is prominent in sympathetic neurons at the time in which satellite glial cells are developing (Deppmann et al.