E11.Full.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Product Monograph

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH PrFLUANXOL® Flupentixol Tablets (as flupentixol dihydrochloride) 0.5 mg, 3 mg, and 5 mg PrFLUANXOL® DEPOT Flupentixol Decanoate Intramuscular Injection 2% and 10% flupentixol decanoate Antipsychotic Agent Lundbeck Canada Inc. Date of Revision: 2600 Alfred-Nobel December 12th, 2017 Suite 400 St-Laurent, QC H4S 0A9 Submission Control No : 209135 Page 1 of 35 Table of Contents PART I: HEALTH PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION .........................................................3 SUMMARY PRODUCT INFORMATION ........................................................................3 INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE ..............................................................................3 CONTRAINDICATIONS ...................................................................................................4 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ..................................................................................4 ADVERSE REACTIONS ..................................................................................................10 DRUG INTERACTIONS ..................................................................................................13 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ..............................................................................15 OVERDOSAGE ................................................................................................................18 ACTION AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY ............................................................19 STORAGE AND STABILITY ..........................................................................................21 -

Properties and Units in Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology

Pure Appl. Chem., Vol. 72, No. 3, pp. 479–552, 2000. © 2000 IUPAC INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF CLINICAL CHEMISTRY AND LABORATORY MEDICINE SCIENTIFIC DIVISION COMMITTEE ON NOMENCLATURE, PROPERTIES, AND UNITS (C-NPU)# and INTERNATIONAL UNION OF PURE AND APPLIED CHEMISTRY CHEMISTRY AND HUMAN HEALTH DIVISION CLINICAL CHEMISTRY SECTION COMMISSION ON NOMENCLATURE, PROPERTIES, AND UNITS (C-NPU)§ PROPERTIES AND UNITS IN THE CLINICAL LABORATORY SCIENCES PART XII. PROPERTIES AND UNITS IN CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY AND TOXICOLOGY (Technical Report) (IFCC–IUPAC 1999) Prepared for publication by HENRIK OLESEN1, DAVID COWAN2, RAFAEL DE LA TORRE3 , IVAN BRUUNSHUUS1, MORTEN ROHDE1, and DESMOND KENNY4 1Office of Laboratory Informatics, Copenhagen University Hospital (Rigshospitalet), Copenhagen, Denmark; 2Drug Control Centre, London University, King’s College, London, UK; 3IMIM, Dr. Aiguader 80, Barcelona, Spain; 4Dept. of Clinical Biochemistry, Our Lady’s Hospital for Sick Children, Crumlin, Dublin 12, Ireland #§The combined Memberships of the Committee and the Commission (C-NPU) during the preparation of this report (1994–1996) were as follows: Chairman: H. Olesen (Denmark, 1989–1995); D. Kenny (Ireland, 1996); Members: X. Fuentes-Arderiu (Spain, 1991–1997); J. G. Hill (Canada, 1987–1997); D. Kenny (Ireland, 1994–1997); H. Olesen (Denmark, 1985–1995); P. L. Storring (UK, 1989–1995); P. Soares de Araujo (Brazil, 1994–1997); R. Dybkær (Denmark, 1996–1997); C. McDonald (USA, 1996–1997). Please forward comments to: H. Olesen, Office of Laboratory Informatics 76-6-1, Copenhagen University Hospital (Rigshospitalet), 9 Blegdamsvej, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] Republication or reproduction of this report or its storage and/or dissemination by electronic means is permitted without the need for formal IUPAC permission on condition that an acknowledgment, with full reference to the source, along with use of the copyright symbol ©, the name IUPAC, and the year of publication, are prominently visible. -

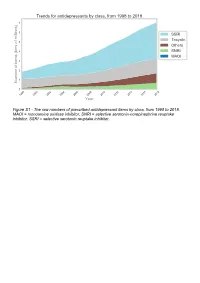

The Raw Numbers of Prescribed Antidepressant Items by Class, from 1998 to 2018

Figure S1 - The raw numbers of prescribed antidepressant items by class, from 1998 to 2018. MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor, SNRI = selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Figure S2 - The raw numbers of prescribed antidepressant items for the ten most commonly prescribed antidepressants (in 2018), from 1998 to 2018. Figure S3 - Practice level percentile charts for the proportions of the ten most commonly prescribed antidepressants (in 2018), prescribed between August 2010 and November 2019. Deciles are in blue, with median shown as a heavy blue line, and extreme percentiles are in red. Figure S4 - Practice level percentile charts for the proportions of specific MAOIs prescribed between August 2010 and November 2019. Deciles are in blue, with median shown as a heavy blue line, and extreme percentiles are in red. Figure S5 - CCG level heat map for the percentage proportions of MAOIs prescribed between December 2018 and November 2019. MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Figure S6 - CCG level heat maps for the percentage proportions of paroxetine, dosulepin, and trimipramine prescribed between December 2018 and November 2019. Table S1 - Antidepressant drugs, by category. MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor, SNRI = selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Class Drug MAOI Isocarboxazid, moclobemide, phenelzine, tranylcypromine SNRI Duloxetine, venlafaxine SSRI Citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, -

Depot Antipsychotic Injections

Mental Health Services Good Practice Statement For The Use Of DEPOT & LONG ACTING ANTIPSYCHOTIC INJECTIONS Date of Revision: February 2020 Approved by: Mental Health Prescribing Management Group Review Date: CONSULTATION The document was sent to Community Mental Health teams, Pharmacy and the Psychiatric Advisory Committee for comments prior to completion. KEY DOCUMENTS When reading this policy please consult the NHS Consent Policy when considering any aspect of consent National Institute for Clinical Excellence CG178 (2014), Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management NHS Lothian (2011), Depot Antipsychotic Guidance, Maudsley (2015), Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry 12th edition. UKPPG (2009) Guidance on the Administration to Adults of Oil based Depot and other Long Acting Intramuscular Antipsychotic Injections Summary of Product Characteristics for: Clopixol (Zuclopethixol Decanoate) Flupenthixol Decanoate Haldol (Haloperidol Decanoate) Risperdal Consta Xeplion (Paliperidone Palmitate) ZypAdhera (Olanzapine Embonate) Abilify Maintena (Aripiprazole) 1 CONTENTS REFERENCES/KEY DOCUMENTS …………………………………………………………… 1 INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………………………. 3 SCOPE …………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 DEFINITIONS ……………………………………………………………………………………... 3 CHOICE OF DRUG AND DOSAGE SELECTION ……………………………………………. 3 SIDE EFFECTS ……………………………………………………………….………………….. 5 PRESCRIBING …………………………………………………………………………………… 5 ADMINISTRATION ………………………………………………………………………………. 7 RECORDING ADMINISTRATION ……………………………………………………………… 7 -

Deanxit SPC.Pdf

SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Deanxit film-coated tablets 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each tablet contains: Flupentixol 0.5 mg (as 0.584 mg flupentixol dihydrochloride) Melitracen 10 mg (as 11.25 mg melitracen hydrochloride) Excipients with known effect: Lactose monohydrate For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Film-coated tablets. Round, biconvex, cyclamen, film-coated tablets. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Anxiety Depression Asthenia. Neurasthenia. Psychogenic depression. Depressive neuroses. Masked depression. Psychosomatic affections accompanied by anxiety and apathy. Menopausal depressions. Dysphoria and depression in alcoholics and drug-addicts. 4.2 Posology and method of administration Posology Adults Usually 2 tablets daily: morning and noon. In severe cases the morning dose may be increased to 2 tablets. The maximum dose is 4 tablets daily. Older people (> 65 years) 1 tablet in the morning. In severe cases 1 tablet in the morning and 1 at noon. Maintenance dose: Usually 1 tablet in the morning. SPC Portrait-REG_00051968 20v038 Page 1 of 10 In cases of insomnia or severe restlessness additional treatment with a sedative in the acute phase is recommended. Paediatric population Children and adolescents (<18 years) Deanxit is not recommended for use in children and adolescents due to lack of data on safety and efficacy. Reduced renal function Deanxit can be given in the recommended doses. Reduced liver function Deanxit can be given in the recommended doses. Method of administration The tablets are swallowed with water. 4.3 Contraindications Hypersensitivity to flupentixol and melitracen or to any of the excipients listed in section 6.1. -

020592Orig1s040s041

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 020592Orig1s040s041 MEDICAL REVIEW(S) M E M O R A N D U M DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH DATE: July 18, 2008 FROM: Ni A. Khin, M.D. Team Leader Division of Psychiatry Products, HFD-130 TO: NDA 20-592/SE5-040 (bipolar I disorder, acute mania) NDA 20-592/SE5-041 (schizophrenia) (This overview should be filed with the 02-05-2008 submission in response to the Agency’s Approvable Letter dated 04-30-2007) SUBJECT: Recommendation of an approvable action for use of Zyprexa (olanzapine) in the treatment of 1) Bipolar I disorder, Mania, and 2) schizophrenia in Adolescents. 1. BACKGROUND Zyprexa (olanzapine) is an atypical antipsychotic agent, approved in the U.S. for treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, mania or mixed episodes, as monotherapy (both acute and maintenance) or combination therapy in adults. It is available as oral 2.5, 5, 10, 15, or 20 mg strength tablets; 5, 10, 15, or 20 mg oral disintegrating tablets (Zydis). The target dose for adults with schizophrenia is 10 mg/day. Zyprexa intramuscular injection (10 mg) is indicated for agitation associated with schizophrenia and Bipolar I Mania. Currently, two atypical antipsychotic drugs, Risperdal and Abilify, are approved for treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in the pediatric population. In response to the Agency’s written request (original 11/30/2001; amended 4/9/02, 7/3/02, 5/7/04, 6/29/05), the sponsor conducted clinical trials for two indications: schizophrenia (F1D-MC-HGIN) and bipolar disorder (F1D-MC-HGIU) in adolescents, and submitted the study results to the above referenced supplemental NDA on 10/30/2006. -

Package Leaflet: Information for the Patient Depixol® 20 Mg/Ml Solution

Package leaflet: Information for the patient Depixol® 20 mg/ml solution for injection flupentixol decanoate Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start using this medicine because it contains important information for you. • Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again • If you have any further questions, ask your doctor, pharmacist or nurse • This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their signs of illness are the same as yours • If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor, pharmacist or nurse. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet: 1. What Depixol Injection is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before Depixol Injection is given 3. How Depixol Injection is given 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store Depixol Injection 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What Depixol Injection is and what it is used for The name of your medicine is Depixol 20 mg/ml solution for injection (called Depixol Injection in this leaflet). Depixol Injection contains the active substance flupentixol decanoate. Depixol Injection belongs to a group of medicines known as antipsychotics (also called neuroleptics). These medicines act on nerve pathways in specific areas of the brain and help to correct certain chemical imbalances in the brain that are causing the symptoms of your illness. Depixol Injection is used for the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychoses. Your doctor, however, may prescribe Depixol Injection for another purpose. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0005722 A1 Jennings-Spring (43) Pub

US 20090005722A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0005722 A1 Jennings-Spring (43) Pub. Date: Jan. 1, 2009 (54) SKIN-CONTACTING-ADHESIVE FREE Publication Classification DRESSING (51) Int. Cl. Inventor: Barbara Jennings-Spring, Jupiter, A61N L/30 (2006.01) (76) A6F I3/00 (2006.01) FL (US) A6IL I5/00 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: AOIG 7/06 (2006.01) Irving M. Fishman AOIG 7/04 (2006.01) c/o Cohen, Tauber, Spievack and Wagner (52) U.S. Cl. .................. 604/20: 602/43: 602/48; 4771.5; Suite 2400, 420 Lexington Avenue 47/13 New York, NY 10170 (US) (57) ABSTRACT (21) Appl. No.: 12/231,104 A dressing having a flexible sleeve shaped to accommodate a Substantially cylindrical body portion, the sleeve having a (22) Filed: Aug. 29, 2008 lining which is substantially non-adherent to the body part being bandaged and having a peripheral securement means Related U.S. Application Data which attaches two peripheral portions to each other without (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. 1 1/434,689, those portions being circumferentially adhered to the sleeve filed on May 16, 2006. portion. Patent Application Publication Jan. 1, 2009 Sheet 1 of 9 US 2009/0005722 A1 Patent Application Publication Jan. 1, 2009 Sheet 2 of 9 US 2009/0005722 A1 10 8 F.G. 5 Patent Application Publication Jan. 1, 2009 Sheet 3 of 9 US 2009/0005722 A1 13 FIG.6 2 - Y TIII Till "T fift 11 10 FIG.7 8 13 6 - 12 - Timir" "in "in "MINIII. -

Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Second Generation

Forensic Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Exactive Plus High-Resolution Accurate Mass Spectrometer and ExactFinder Software Kristine Van Natta, Marta Kozak, Xiang He Forensic Toxicology use Only Drugs analyzed Compound Compound Compound Atazanavir Efavirenz Pyrilamine Chlorpropamide Haloperidol Tolbutamide 1-(3-Chlorophenyl)piperazine Des(2-hydroxyethyl)opipramol Pentazocine Atenolol EMDP Quinidine Chlorprothixene Hydrocodone Tramadol 10-hydroxycarbazepine Desalkylflurazepam Perimetazine Atropine Ephedrine Quinine Cilazapril Hydromorphone Trazodone 5-(p-Methylphenyl)-5-phenylhydantoin Desipramine Phenacetin Benperidol Escitalopram Quinupramine Cinchonine Hydroquinine Triazolam 6-Acetylcodeine Desmethylcitalopram Phenazone Benzoylecgonine Esmolol Ranitidine Cinnarizine Hydroxychloroquine Trifluoperazine Bepridil Estazolam Reserpine 6-Monoacetylmorphine Desmethylcitalopram Phencyclidine Cisapride HydroxyItraconazole Trifluperidol Betaxolol Ethyl Loflazepate Risperidone 7(2,3dihydroxypropyl)Theophylline Desmethylclozapine Phenylbutazone Clenbuterol Hydroxyzine Triflupromazine Bezafibrate Ethylamphetamine Ritonavir 7-Aminoclonazepam Desmethyldoxepin Pholcodine Clobazam Ibogaine Trihexyphenidyl Biperiden Etifoxine Ropivacaine 7-Aminoflunitrazepam Desmethylmirtazapine Pimozide Clofibrate Imatinib Trimeprazine Bisoprolol Etodolac Rufinamide 9-hydroxy-risperidone Desmethylnefopam Pindolol Clomethiazole Imipramine Trimetazidine Bromazepam Felbamate Secobarbital Clomipramine Indalpine Trimethoprim Acepromazine Desmethyltramadol Pipamperone -

Flupentixol Compositions

(19) & (11) EP 2 374 450 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 12.10.2011 Bulletin 2011/41 A61K 9/20 (2006.01) A61K 47/40 (2006.01) A61K 45/06 (2006.01) A61K 31/496 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 10159137.8 A61K 31/135 A61P 25/22 A61P 25/24 (2006.01) A61P 25/18 (2006.01) (22) Date of filing: 06.04.2010 (84) Designated Contracting States: (72) Inventor: Olsen, Flemming, Enok AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR 3450, Allerød (DK) HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO PL PT RO SE SI SK SM TR Remarks: Designated Extension States: Amended claims in accordance with Rule 137(2) AL BA ME RS EPC. (71) Applicant: H. Lundbeck A/S 2500 Valby (DK) (54) Flupentixol compositions (57) Compositions comprising flupentixol and cyclodextrin are provided. EP 2 374 450 A1 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) EP 2 374 450 A1 Description Field of invention 5 [0001] Flupentixol is an antipsychotic of the thioxanthene group. Flupentixol has the structure depicted below 10 15 and the systematic name 2-(4-{3-[2-trifluoromethyl-thioxanthen-(9E)-ylidene]-propyl}-piperazin-1-yl)-ethanol. The com- pound was first disclosed in the GB patent 925538 to Smith Kline & French Laboratories in 1963 and said to have e.g. tranquilising and general central nervous system depressant activity. Flupentixol has been marketed as the dihydro- 20 chloride acid salt of the mixed (E)(Z) isomers in tablet form and in solution (Fluanxol®) and also as the (Z) isomer decanoate ester in injectable depot formulations (Depixol®). -

Antidepressants

Antidepressants BMF 83 - Antidepressants BMF 83 - Antidepressants Depression is a common psychiatric disorder impacting millions of people worldwide. It is caused by an imbalance of chemicals 1 in the brain, namely serotonin and noradrenaline . Everyone experiences highs and lows, but depression is characterised by 2 persistent sadness for weeks or months . With depression there is lasting feeling of hopelessness, often accompanied by anxiety. Sufferers lose interest in things that they previously enjoyed, and experience bouts of tearfulness. Rational thinking and decision 2 making are impacted. Physical manifestations include tiredness, insomnia, loss of appetite and sex drive, aches and pains . At its worst depression can cause the sufferer to feel suicidal. Depression is usually treated with a combination of counselling and drug therapy. There is also evidence that exercise can help depression. Most people with moderate or severe depression benefit from antidepressant medication. There are a wide range of 3 antidepressants on the market, which can be broadly divided according to mechanism of action ; • Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) • Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) • Serotonin modulator and stimulators (SMSs) • Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors (SARIs) • Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs or NERIs) • Tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs) • Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) • Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) www.chiron.no | E-mail: [email protected] | Tel.: +47 73 87 44 90 | Fax.: +47 73 73 87 44 99 | BMF 83 p.1/8 , 10_16 BMF 83 - Antidepressants BMF 83 - Antidepressants 1 Today the most common first choice of medication is a SSRI , i.e. Citalopram, Escitalopram, Fluvoxamine, Paroxetine, Sertraline, Fluoxetine. Antidepressants are not addictive, but can result in withdrawal symptoms when therapy is stopped. -

Guidance on the Treatment of Antipsychotic Induced Hyperprolactinaemia in Adults

Guidance on the Treatment of Antipsychotic Induced Hyperprolactinaemia in Adults Version 1 GUIDELINE NO RATIFYING COMMITTEE DRUGS AND THERAPEUTICS GROUP DATE RATIFIED April 2014 DATE AVAILABLE ON INTRANET NEXT REVIEW DATE April 2016 POLICY AUTHORS Nana Tomova, Clinical Pharmacist Dr Richard Whale, Consultant Psychiatrist In association with: Dr Gordon Caldwell, Consultant Physician, WSHT . If you require this document in an alternative format, ie easy read, large text, audio, Braille or a community language, please contact the Pharmacy Team on 01243 623349 (Text Relay calls welcome). Contents Section Title Page Number 1. Introduction 2 2. Causes of Hyperprolactinaemia 2 3. Antipsychotics Associated with 3 Hyperprolactinaemia 4. Effects of Hyperprolactinaemia 4 5. Long-term Complications of Hyperprolactinaemia 4 5.1 Sexual Development in Adolescents 4 5.2 Osteoporosis 4 5.3 Breast Cancer 5 6. Monitoring & Baseline Prolactin Levels 5 7. Management of Hyperprolactinaemia 6 8. Pharmacological Treatment of 7 Hyperprolactinaemia 8.1 Aripiprazole 7 8.2 Dopamine Agonists 8 8.3 Oestrogen and Testosterone 9 8.4 Herbal Remedies 9 9. References 10 1 1.0 Introduction Prolactin is a hormone which is secreted from the lactotroph cells in the anterior pituitary gland under the influence of dopamine, which exerts an inhibitory effect on prolactin secretion1. A reduction in dopaminergic input to the lactotroph cells results in a rapid increase in prolactin secretion. Such a reduction in dopamine can occur through the administration of antipsychotics which act on dopamine receptors (specifically D2) in the tuberoinfundibular pathway of the brain2. The administration of antipsychotic medication is responsible for the high prevalence of hyperprolactinaemia in people with severe mental illness1.