Portland, Oregon, USA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WORKING DOCDRAFT Charter Directors Handbook .Docx

PPS Resource Guide A guide for new arrivals to Portland and the Pacific Northwest PPS Resource Guide PPS Resource Guide Portland Public Schools recognizes the diversity and worth of all individuals and groups and their roles in society. It is the policy of the Portland Public Schools Board of Education that there will be no discrimination or harassment of individuals or groups on the grounds of age, color, creed, disability, marital status, national origin, race, religion, sex or sexual orientation in any educational programs, activities or employment. 3 PPS Resource Guide Table of Contents How to Use this Guide ....................................................................................................................6 About Portland Public Schools (letter from HR) ...............................................................................7 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................8 Cities, Counties and School Districts .............................................................................................. 10 Multnomah County .............................................................................................................................. 10 Washington County ............................................................................................................................. 10 Clackamas County ............................................................................................................................... -

District Background

DRAFT SOUTHEAST LIAISON DISTRICT PROFILE DRAFT Introduction In 2004 the Bureau of Planning launched the District Liaison Program which assigns a City Planner to each of Portland’s designated liaison districts. Each planner acts as the Bureau’s primary contact between community residents, nonprofit groups and other government agencies on planning and development matters within their assigned district. As part of this program, District Profiles were compiled to provide a survey of the existing conditions, issues and neighborhood/community plans within each of the liaison districts. The Profiles will form a base of information for communities to make informed decisions about future development. This report is also intended to serve as a tool for planners and decision-makers to monitor the implementation of existing plans and facilitate future planning. The Profiles will also contribute to the ongoing dialogue and exchange of information between the Bureau of Planning, the community, and other City Bureaus regarding district planning issues and priorities. PLEASE NOTE: The content of this document remains a work-in-progress of the Bureau of Planning’s District Liaison Program. Feedback is appreciated. Area Description Boundaries The Southeast District lies just east of downtown covering roughly 17,600 acres. The District is bordered by the Willamette River to the west, the Banfield Freeway (I-84) to the north, SE 82nd and I- 205 to the east, and Clackamas County to the south. Bureau of Planning - 08/03/05 Southeast District Page 1 Profile Demographic Data Population Southeast Portland experienced modest population growth (3.1%) compared to the City as a whole (8.7%). -

Download PDF File Delta Park Economic Analysis Study

The Impact of Portland’s Delta Park An Economic Analysis Before and After Proposed Facility Improvements May 2017 Prepared for: Portland Parks & Recreation KOIN Center 222 SW Columbia Street Suite 1600 Portland, OR 97201 503.222.6060 This page intentionally blank Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 4 ECONOMIC IMPACT ANALYSIS 5 BASELINE ECONOMIC IMPACTS 7 PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL RACEWAY 7 Individual User Survey 7 Baseline Economic Impacts of PIR 16 DELTA PARK OWENS SPORTS COMPLEX 18 Individual User Survey 18 Baseline Economic Impacts of the Sports Complex 25 HERON LAKES GOLF CLUB 27 Individual User Survey 27 Baseline Economic Impacts of Heron Lakes 33 ECONOMIC IMPACTS IN THE FUTURE 36 LIST OF FUTURE IMPROVEMENTS 36 User Group Interviews 37 PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL RACEWAY 38 Key Takeaways from Interviews 38 Future Visitation 39 Future Operations 39 Economic Impacts 39 DELTA PARK OWENS SPORTS COMPLEX 41 Key Takeaways from Interviews 41 Future Visitation 41 Economic Impacts 43 HERON LAKES GOLF CLUB 44 Key Takeaways from Interviews 44 Future Visitation 44 Economic Impacts 46 HOTEL ANALYSIS 47 The Market 47 Historical Trends 50 New Hotel Concept 53 CONCLUSIONS 57 Recommendations 57 APPENDIX A. INDIVIDUAL SURVEY QUESTIONS 58 Visitor Survey Questions 58 APPENDIX B. ECONOMIC IMPACT TERMS AND DEFINITIONS 61 Gross Contributions vs. Net Impacts 62 Executive Summary The Portland Parks and Recreation asked ECONorthwest for an analysis of the current and future economic impacts of the three sports facilities located at Delta Park in north Portland—Portland International Raceway, Delta Park Owens Sports Complex, and the Heron Lakes Golf Club. The purpose of this report is to inform the agency’s facilities planning. -

The Fields Neighborhood Park Community Questionnaire Results March-April 2007

The Fields Neighborhood Park Community Questionnaire Results March-April 2007 A Community Questionnaire was included in the initial project newsletter, which was mailed to over 4,000 addresses in the vicinity of the park site (virtually the entire neighborhood) as well as other interested parties. The newsletter was made available for pick-up at Chapman School and Friendly House and made available electronically as well. A total of 148 questionnaires were submitted, either by mail or on the web, by the April 20 deadline. The following summarizes the results. 1. The original framework plan for the River District Parks suggested three common elements that would link the parks together. Which do you feel should be included in The Fields neighborhood park? 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Boardwalk Pedestrian Gallery Aquifer 2. This park is envisioned as a “neighborhood park no answ er – over two square blocks providing more traditional spaces for neighborhood residents. Do you agree ? with this overall concept? no yes Comments Regarding Question #2 “Traditional Neighborhood Park” #1 - None (of the original “framework concepts” are important What to you mean by "traditional" As long as this park does not become filthy (ie. bad terrain, homeless) like the waterfront, I'm for it. Excellent idea. A traditional park will be a nice complement to the other two parks. I don't know if my selections were recorded above. A continuation of the boardwalk is essential to making the connection between and among the parks. The design of the buildings around the park has narrowed the feeling of openness so it is beginning to look like a private park for the residential buildings surrounding it. -

Oregon's Recent Past

Oregon’s Recent Past: North Willamette Valley, Portland, Columbia River, Mt. Hood. Written by RW. Faulkner Recent Photos by RW. Faulkner & MS. Faulkner ©= RW Faulkner 5/17/2018 All Rights Reserved First Printing August 2018 ISBN: 978-0-9983622-6-7 About the Cover Above Left Front Cover Above Right Back Cover Top Photo: Mt. Hood by FH Shogren, perhaps taken Top Photo: Clive E. Long, a Portland printer, near NW Thurman Street, Portland OR. Photo was & perhaps Clayton Van Riper of Dayton Ohio, featured in the 1905 Lewis & Clark Souvenir rest while climbing Mt. Hood, August 16, 1907. Program, (LC), titled, “Snow-Capped Mt. Hood, Seen Map: Copy of map of the northern Willamette Across The Exposition City,” & described by Rinaldo Valley. Original traced/drawn on tissue paper. M. Hall as, “Not every day may Mt. Hood be seen at It was used by pioneer Dr. Marcus Hudson its best, for clouds ever hover ‘round it, but the White to navigate, soon after his arrival in1891. constant watcher is frequently rewarded by seeing it (Found in a small notebook with most entries stand forth clearly & glisten in the sunlight as a dating 1892-1895, but map could be from mountain of silver. ...50 miles east of Portland by air 1891-1897.) line & 93 by shortest route, this favorite proudly rears its head 11,225 feet heavenward, thousands of feet above every neighboring object. It is one of the most notable peaks in the West, serving as a guide post to Lewis & Clark on their memorable trip of exploration to the coast in 1805-06, & later to the pioneers who hastened on to Western Oregon....” Lower Photo Mt. -

FRG17 Online-1.Pdf

Tualatin Dance Center - 8487 SW Warm Krayon Kids Musical Theater Co. - 817 12th, ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT Springs, Tualatin; 503-691-2414; facebook.com. Oregon City; 503-656-6099; krayonkids.org. Musical theater featuring local children. ART GALLERIES in camps and classes, plus supplies for at-home projects. Ladybug Theater - 8210 SE 13th; 502-232- & EXHIBITS DRAMA / THEATER 2346; ladybugtheater.com. Wed. morning Vine Gogh Artist Bar & Studio - 11513 SW Pa- Northwest Children’s Theater performances for young children with audience Oregon Historical Society cific Hwy, Tigard; 971-266-8983; vinegogh.com. participation. and School Visit our new permanent exhibit History Public painting classes for all ages. Hub where families can explore the topic of NWCT produces award-winning children’s Lakewood Theatre Company - 368 S State, diversity through fun, hands-on interactives. Young Art Lessons - 7441 SW Bridgeport; 503- theater productions and is one of the largest Lake Oswego; 503-635-3901; lakewood-center. With puzzles, touch screen activities, and board 336-0611; 9585 SW Washington Sq; 503-352- theater schools on the West Coast. NWCT org. Live theater and classes for kids and adults. games, History Hub asks students to consider 5965; youngartusa.co. keeps the magic of live performance accessible questions like “Who is an Oregonian?,” and and affordable to over 65,000 families annually Portland Revels - 1515 SW Morrison Street; “How can you make Oregon a great place for with a mission to educate, entertain, and enrich 503-274-4654; portlandrevels.org. Seasonal everyone?” the lives of young audiences. performances feature song, dance, story and DANCE ritual of the past and present. -

Trail Running in the Portland Area

TRAIL RUNNING IN THE PORTLAND AREA Banks-Vernonia State Trail Activity: Trail Running Buxton, OR Trail Distance: 4 miles A wide gravel multi-use trail that travels through a second-growth Douglas fir forest. You’ll enjoy the smooth graded surface on this 20-mile multi-use trail that travels through a serene forest canopy. Clackamas River Activity: Trail Running Estacada, OR Trail Distance: 8 miles A classic river trail that traces the contours of the Clackamas River through pockets of old- growth western red cedar and Douglas fir. River views. Creek crossings. Bridge crossings. Glendover Fitness Trail Loop Activity: Trail Running Portland, OR Trail Distance: 2 miles Wood-chip trail (with a short paved section) that circles Glendoveer Golf Course in northeast Portland. This sophisticated wood- chip trail circles the smooth greens of Glendoveer Golf Course in northe... Hagg Lake Loop Activity: Trail Running Forest Grove, OR Trail Distance: 15.1 miles Combination of singletrack trail, paved paths, and roads that take you around scenic Hagg Lake in Scoggins Valley Regional Park in Washington County. Bridge crossings. This sinewy trail offers plenty ... Leif Erikson Drive Activity: Trail Running Portland, OR Trail Distance: 12 miles Nonmotorized multi-use gravel-dirt road with distance markers that winds through 5,000- acre Forest Park in Portland. Occasional views. This civilized multi-use trail is an easy cruise on a multi-use g... Leif Erikson Drive - Wildwood Loop Activity: Trail Running Portland, OR Trail Distance: 7.9 miles The route travels on singletrack trails and a doubletrack gravel road through the scenic treed setting of Forest Park. -

2021 Reciprocal Admissions Program

AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY 2021 RECIPROCAL ADMISSIONS PROGRAM Participating Gardens, Arboreta, and Conservatories For details on benefits and 90-mile radius enforcement, see https://ahsgardening.org/gardening-programs/rap Program Guidelines: A current membership card from the American Horticultural Society (AHS) or a participating RAP garden entitles the visitor to special admissions privileges and/or discounts at many different types of gardens. The AHS provides the following guidelines to its members and the members of participating gardens for enjoying their RAP benefits: This printable document is a listing of all sites that participate in the American Horticultural Society’s Reciprocal Admissions Program. This listing does not include information about the benefit(s) that each site offers. For details on benefits and enforcement of the 90- mile radius exclusion, see https://ahsgardening.org/gardening-programs/rap Call the garden you would like to visit ahead of time. Some gardens have exclusions for special events, for visitors who live within 90 miles of the garden, etc. Each garden has its own unique admissions policy, RAP benefits, and hours of operations. Calling ahead ensures that you get the most up to date information. Present your current membership card to receive the RAP benefit(s) for that garden. Each card will only admit the individual(s) whose name is listed on the card. In the case of a family, couple, or household membership card that does not list names, the garden must extend the benefit(s) to at least two of the members. Beyond this, gardens will refer to their own policies regarding household/family memberships. -

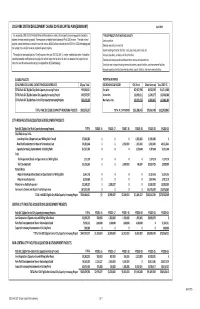

2015 DRAFT Park SDC Capital Plan 150412.Xlsx

2015 PARK SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT CHARGE 20‐YEAR CAPITAL PLAN (SUMMARY) April 2015 As required by ORS 223.309 Portland Parks and Recreation maintains a list of capacity increasing projects intended to TYPES OF PROJECTS THAT INCREASE CAPACITY: address the need created by growth. These projects are eligible to be funding with Park SDC revenue . The total value of Land acquisition projects summarized below exceeds the potential revenue of $552 million estimated by the 2015 Park SDC Methodology and Develop new parks on new land the funding from non-SDC revenue targeted for growth projects. Expand existing recreation facilities, trails, play areas, picnic areas, etc The project list and capital plan is a "living" document that, per ORS 223.309 (2), maybe modified at anytime. It should be Increase playability, durability and life of facilities noted that potential modifications to the project list will not impact the fee since the fee is not based on the project list, but Develop and improve parks to withstand more intense and extended use rather the level of service established by the adopted Park SDC Methodology. Construct new or expand existing community centers, aquatic facilities, and maintenance facilities Increase capacity of existing community centers, aquatic facilities, and maintenance facilities ELIGIBLE PROJECTS POTENTIAL REVENUE TOTAL PARK SDC ELIGIBLE CAPACITY INCREASING PROJECTS 20‐year Total SDC REVENUE CATEGORY SDC Funds Other Revenue Total 2015‐35 TOTAL Park SDC Eligible City‐Wide Capacity Increasing Projects 566,640,621 City‐Wide -

RFP NUMBER 00000617 City of Portland, Oregon REQUEST FOR

RFP NUMBER 00000617 City of Portland, Oregon May 4, 2017 REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS FOR PORTLAND OPEN SPACE SEQUENCE RESTORATION PROJECT CONSTRUCTION MANAGER / GENERAL CONTRACTOR SERVICES PROPOSALS DUE: May 31, 2017 by 4:00 p.m. Response Envelope(s) shall be sealed and marked with RFP Number and Project Title. SUBMITTAL INFORMATION: Refer to PART II, SECTION B. PROPOSAL SUBMISSION Submit the Proposal to: Procurement Services City of Portland 1120 SW Fifth Avenue, Room 750 Portland, OR 97204 Attn: Celeste King Refer questions to: Celeste King City of Portland, Procurement Services Phone: (503) 823-4044 Fax : (503) 865-3455 Email: [email protected] A MANDATORY PRE-PROPOSAL MEETING has been scheduled for Thurs, May 18, 2017, at 1:30 pm starting at Ira Keller Fountain at SW Third & Clay Streets, Portland, OR 97204. TABLE OF CONTENTS . Notice to Proposers . General Instructions and Conditions of the RFP . Project Contacts . Part I: Solicitation Requirements Section A General Information Section B CM/GC Services Section C Exhibits Section D Proposal Forms . Part II: Proposal Preparation and Submittal Section A Pre-Proposal Meeting / Clarification Section B Proposal Submission Section C Proposal Content and Evaluation Criteria . Part III: Proposal Evaluation Section A Proposal Review and Selection Section B Contract Award . Exhibits Exhibit A CM/GC Disadvantaged, Minority, Women and Emerging Small Business Subcontractor and Supplier Plan Exhibit B Workforce Training and Hiring Program Exhibit C General Conditions of the Contract for CM/GC Projects Exhibit D Sample Pre-Construction Services Contract Exhibit E Sample Construction Contract Exhibit F Assignment of Anti Trust Rights Exhibit G CM/GC & Owner Team Roles and Responsibilities Table Exhibit H Design Team Contract Exhibit I Public Information Plan Exhibit J Project Validation Report for Lovejoy Fountain Rehabilitation Exhibit K Anticipated Project Schedule Exhibit L 30% Cost Estimate Exhibit M 30% Specification Table of Contents Exhibit N 30% Construction Drawings . -

Noise Analysis of Eastbank Esplanade

Appendix F. Updated Memorandum: Noise Analysis of Eastbank Esplanade UPDATED MEMORANDUM: Noise Analysis of Eastbank Esplanade 1-5 Rose Quarter Improvement Project Orlglnal: May 31, 2019 Updated: September 16, 2020 Note: This analysis has been updated to reflectthe Build alternate as shown in the Revised Environmental Assessment. Analysis by: Daniel Burgin, ODOT Noise Program Coordinator Reviewed by: Natalie Liljenwall, P.E., Air Quality Program Coordinator and Noise Engineer RENEWS: 12-31-2020 Executive Summary This memorandum documents a noise analysis conducted by Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) to analyze noise impacts at the Eastbank Esplanade in Portland, Oregon. In January 2019, a Noise Study Technical Report for the I‐5 Rose Quarter Improvement Project was published as a part of the Environmental Assessment for the project. The Eastbank Esplanade was not included as a noise sensitive land use in that analysis because ODOT does not typically consider bicycle and pedestrian facilities as noise sensitive resources unless they are clearly recreational rather than for transportation use such that users spend at least an hour at one location. Since then, it has been determined that the Eastbank Esplanade is a park. As a park, the Eastbank Esplanade is classified as Noise Abatement Criteria (NAC) Category C. (Refer to Table 3.) Category C receptors are considered noise sensitive and are to be included in federally funded highway noise analysis. This noise analysis showed that the Eastbank Esplanade is noise impacted with the project (72 dBA in design year) however, no mitigation is recommended for this location because it is not cost reasonable based on usage. -

The Boring Volcanic Field of the Portland-Vancouver Area, Oregon and Washington: Tectonically Anomalous Forearc Volcanism in an Urban Setting

Downloaded from fieldguides.gsapubs.org on April 29, 2010 The Geological Society of America Field Guide 15 2009 The Boring Volcanic Field of the Portland-Vancouver area, Oregon and Washington: Tectonically anomalous forearc volcanism in an urban setting Russell C. Evarts U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefi eld Road, Menlo Park, California 94025, USA Richard M. Conrey GeoAnalytical Laboratory, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington 99164, USA Robert J. Fleck Jonathan T. Hagstrum U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefi eld Road, Menlo Park, California 94025, USA ABSTRACT More than 80 small volcanoes are scattered throughout the Portland-Vancouver metropolitan area of northwestern Oregon and southwestern Washington. These vol- canoes constitute the Boring Volcanic Field, which is centered in the Neogene Port- land Basin and merges to the east with coeval volcanic centers of the High Cascade volcanic arc. Although the character of volcanic activity is typical of many mono- genetic volcanic fi elds, its tectonic setting is not, being located in the forearc of the Cascadia subduction system well trenchward of the volcanic-arc axis. The history and petrology of this anomalous volcanic fi eld have been elucidated by a comprehensive program of geologic mapping, geochemistry, 40Ar/39Ar geochronology, and paleomag- netic studies. Volcanism began at 2.6 Ma with eruption of low-K tholeiite and related lavas in the southern part of the Portland Basin. At 1.6 Ma, following a hiatus of ~0.8 m.y., similar lavas erupted a few kilometers to the north, after which volcanism became widely dispersed, compositionally variable, and more or less continuous, with an average recurrence interval of 15,000 yr.