The Expression of Gentility in Colonial America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coloring Their World: Americans and Decorative Color in the Nineteenth Century

Coloring Their World: Americans and Decorative Color in the Nineteenth Century A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences by Kelly F. Wright B.A. College of William and Mary 1985 M.A. University of Cincinnati 2001 Committee Chair: Wayne K. Durrill, Ph.D. i ABSTRACT Certain events in recent history have called into question some long-held assumptions about the colors of our material history. The controversy over the cleaning of the Sistine Chapel posited questions about color to an international audience, and in the United States the restoration of original decorative colors at the homes of many historically significant figures and religious groups has elicited a visceral reaction suggesting the new colors challenge Americans’ entrenched notions of what constituted respectable taste, if not comportment, in their forebears. Recent studies have even demonstrated that something as seemingly objective as photography has greatly misled us about the appearance of our past. We tend to see the nineteenth century as a faded, sepia-toned monochrome. But nothing could be further from the truth. Coloring Their World: Americans and Decorative Color in the Nineteenth Century, argues that in that century we can witness one of the only true democratizations in American history—the diffusion of color throughout every level of society. In the eighteenth century American aristocrats brandished color like a weapon, carefully crafting the material world around them as a critical part of their political and social identities, cognizant of the power afforded them by color’s correct use, and the consequences of failure. -

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

2019 – Spring Newsletter

News From Red Hill Published By the Patrick Henry Memorial Foundation — Brookneal, VA Ribbon Cutting and Grand Opening On April 26th, the long-awaited day finally arrived for the grand unveiling of Red Hill’s newly completed Eugene B. Casey Education and Events Center. Celebrations began Thursday evening with a VIP preview of the building for members of the Patrick Henry Descendants’ Branch and special guests. Friday marked the main event with the official ribbon cutting and a catered party and presentations in (continued on page 2) Celebrating The Life of In This Issue... Mrs. Edith Poindexter On the morning of March including her son Cole Poindexter, Red Hill Collection 11, 2019, Edith Cabaniss Poindexter, who has inherited her role as Henry Page 3 91, went to be with her husband Geneaologist. Ms. Marstin shared Jack Robinson Poindexter. that Miz P., “told me many times PHDB Reunion Edith Poindexter—or Miz she wanted some of her ashes to be Page 4 P., as she was affectionately known scattered at this place so precious to at Red Hill—was honored at a cel- her. She deserves to be here, she has Living History Series ebration of life ceremony at the Red earned the right to be here, and I am Page 4 Hill Scatter Garden on April 26th. so happy she will always be a part Those gathered together were able of Patrick Henry’s Red Hill. Let our Alexi Garrett Essay to share stories and memories of the hearts find comfort in this and let Page 6 formidable woman and historian us hold onto our memories of her as whose work was so vital to Red Hill precious gifts.” Faces of Red Hill for many, many years. -

Empire of Tea

Empire of Tea Empire of Tea The Asian Leaf that Conquered the Wor ld Markman Ellis, Richard Coulton, Matthew Mauger reaktion books For Ceri, Bey, Chelle Published by Reaktion Books Ltd 33 Great Sutton Street London ec1v 0dx, uk www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2015 Copyright © Markman Ellis, Richard Coulton, Matthew Mauger 2015 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 978 1 78023 440 3 Contents Introduction 7 one: Early European Encounters with Tea 14 two: Establishing the Taste for Tea in Britain 31 three: The Tea Trade with China 53 four: The Elevation of Tea 73 five: The Natural Philosophy of Tea 93 six: The Market for Tea in Britain 115 seven: The British Way of Tea 139 eight: Smuggling and Taxation 161 nine: The Democratization of Tea Drinking 179 ten: Tea in the Politics of Empire 202 eleven: The National Drink of Victorian Britain 221 twelve: Twentieth-century Tea 247 Epilogue: Global Tea 267 References 277 Bibliography 307 Acknowledgements 315 Photo Acknowledgements 317 Index 319 ‘A Sort of Tea from China’, c. 1700, a material survival of Britain’s encounter with tea in the late seventeenth century. e specimen was acquired by James Cuninghame, a physician and ship’s surgeon who visited Amoy (Xiamen) in 1698–9 and Chusan (Zhoushan) in 1700–1703. -

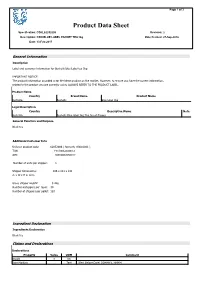

Bushells Blue Label Tea Leaves 3Kg, CON 62252008 Rev 2

Page 1 of 3 Product Data Sheet Specification: CON_62252008 Revision: 2 Description: CON BLUE LABEL PACKET TEA 3kg Date Created: 27-Sep-2016 Date: 13-Feb-2017 General Information Description Label and customer information for Bushells Blue Label tea 3kg IMPORTANT NOTICE: The product information provided is for the latest product on the market. However, to ensure you have the correct information, related to the product you are currently using, ALWAYS REFER TO THE PRODUCT LABEL. Product Name Country Brand Name Product Name Australia Bushells Blue label 3kg Legal Description Country Descriptive Name Note Australia Bushells Blue label 3kg The tea of flavour General Function and Purpose Black tea Additional Customer Info Unilever product code: 62052008 ( formerly 03001001 ) TUN 19310062030012 APN 19310062030012 Number of units per shipper: 1 Shipper Dimensions: 186 x 241 x 241 (L x W x H in mm) Gross shipper weight: 3.4kg Number ofshippers per layer: 30 Number of shippers per pallet: 120 Ingredient Declaration Ingredients Declaration Black tea Claims and Declarations Declarations Property Value UOM Comment Weight 3 kg Date Marking Text (Best Before Date) DDMMYY, HHMM Page 2 of 3 Product Data Sheet Specification: CON_62252008 Revision: 2 Description: CON BLUE LABEL PACKET TEA 3kg Date Created: 27-Sep-2016 Date: 13-Feb-2017 Shelf Life Property Conditions Value UOM Comment Shelf Life Total 24 month(s) Product Origin Property Of Manufacture Of Packing Comment Country Indonesia Indonesia Blended and packed in Indonesia from local and imported teas Risk of Cross Contamination during Processing Information captured in the following property groups relates to the total allergen status of a product i.e. -

Salicylate Food and Product Shopping Lists Last Updated: January 31 2021

p. 1 Salicylate Food and Product Shopping Lists Last Updated: January 31 2021 Formatted for shopping convenience from The Low-Sal Life Go to the website at https://low-sal-life.com/food-product-lists#products for more data on each item, the year and sources for that data, and their complete and awesome list of citations, studies and research: “There have been five major studies testing salicylates in food over the last forty years. I will categorize food by the highest study's levels which includes Free + Bound Salicylic Acid levels, but also include all the historical results. Please take caution while trying new foods. Also note, that the food industry has changed and scientific methods improved in 40 years which may be a few reasons why salicylate levels have changed. Malakar et al. reports all levels with free plus bound salicylic acid, not just free like Swain et al. 1985. This may explain why levels are higher than before. Kęszycka also reports both free and bound, but provides the levels separately. This is why white rice is no longer in the negligible list - it has a low level when including bound salicylic acid. While it's not known how the body metabolizes bound salicylates, it's good to know what the full potential is. The best way to use this list is to search for the food item with your browser search - look for ALL the mentions. For example, figs are listed in three categories depending on how they are preserved. Also, some foods were not included in the five research articles, so I've included items like the St. -

British and Colonial Naturalists Respond to an Enlightenment Creed, 1727–1777

“So Many Things for His Profit and for His Pleasure”: British and Colonial Naturalists Respond to an Enlightenment Creed, 1727–1777 N MAY OF 1773 the Pennsylvania farmer and naturalist John Bartram (1699–1777) wrote to the son of his old colleague Peter Collinson I(1694–1768), the London-based merchant, botanist, and seed trader who had passed away nearly five years earlier, to communicate his worry over the “extirpation of the native inhabitants” living within American forests.1 Michael Collinson returned Bartram’s letter in July of that same year and was stirred by the “striking and curious” observations made by his deceased father’s friend and trusted natural historian from across the Atlantic. The relative threat to humanity posed by the extinction of species generally remained an unresolved issue in the minds of most eighteenth-century naturalists, but the younger Collinson was evidently troubled by the force of Bartram’s remarks. Your comments “carry Conviction along with them,” he wrote, “and indeed I cannot help thinking but that in the period you mention notwithstanding the amazing Recesses your prodigious Continent affords many of the present Species will become extinct.” Both Bartram and Collinson were anxious about certain changes to the environment engendered by more than a century of vigorous Atlantic trade in the colonies’ indigenous flora and fauna. Collinson 1 The terms botanist and naturalist carry different connotations, but are generally used interchange- ably here. Botanists were essentially those men that used Linnaeus’s classification to characterize plant life. They were part of the growing cadre of professional scientists in the eighteenth century who endeavored to efface irrational forms of natural knowledge, i.e., those grounded in folk traditions rather than empirical data. -

Kosher Australia Pesach Guide

Serving the Jewish Community since 1968 GUIDE FOR PESACH & PESACH PRODUCTS 2021 / 5781 as at 7/3/21 81 Balaclava Road, Caulfield North 3161 AUSTRALIA T: +61 (3) 8317 2500, 1300KOSHER (within Australia) W: www.kosher.org.au © 2021 Kosher Australia Pty Ltd Not to be reproduced without permission. Information not to be reproduced without acknowledgement. RABBINIC ADMINISTRATOR: Rabbi Mordechai Gutnick, AM ADVISORY BOARD: Rabbi Danny Mirvis, Rabbi Yonason Johnson, Rabbi Menachem Sabbach BOARD OF MANAGEMENT Mr Stephen Shnider, Llb, Chairman ADMINISTRATION Mr Yankel Wajsbort, B.Sc, C.P.I.M., General Manager Mr Mordi Joseph, B.Bkp, Operations Manager Mr Naftoli Biber, Audit Admin Ms Nechama Ruschinek, Admin Ms Dina Rosenbaum, Admin Mr Eli Paneth, Accounts INVESTIGATIONS Rabbi Kasriel Oliver B.App.Sc., M.R.A.C.I., C.Chem, Chief Chemist Mrs Rose Mehlman B.Sc, Mr Mordechai Hoenders M.Sc, Mr Adam Ruschinek, B.App.Sc Rabbi Yossi Herbst Mr Pesachya Adelist FIELD SUPERVISION Rabbi Arieh Berlin, Rabbi Benjamin Kessly, Rabbi Menachem Sabbach, Rabbi Benyomin Serebryanski, Rabbi Shraga Telsner ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: We are grateful for the assistance of the following in preparing this Guide: Chicago Rabbinical Council, Illinois USA Kof-K, New Jersey USA, London Beth Din, London UK Orthodox Union, New York USA Rabbi A. Adler, Gateshead UK Rabbi G. Bess, Kollel America, Los Angeles USA Star-K, Baltimore USA The Kashrut Authority of NSW, Australia Rabbi YM Levinger, Switzerland Rabbi Danny Moore, BIR, England 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS USING THIS GUIDE .......................................................................................................... 6 PESACH CALENDAR - MARCH 2021 – NISSAN 5781 ......................................................... 6 FOOD OUTLETS IN MELBOURNE ..................................................................................... 7 GENERAL WARNINGS .................................................................................................... -

Annual Report 2015

Artspace ARTSPACE Annual Report 2015 Prepared by Artspace Annual Report 2015 P.1 Artspace TABLE OF CONTENTS MISSION EVER CHANGING, EVER CHALLENGING 2015 Overview & Highlights 6 Artspace is Australiaí s leading interdisciplinary Expanded Artistic Program space for the production and presentation Exhibitions (including Volume 2015 | Another Art Book Fair) 10 of contemporary art. Through exhibitions, Ideas Platform 20 performances, artist residencies, and public International Partnerships & Commissioned work 32 programs, Artspace is where artists of all National and Regional Touring 34 Public Programs 36 generations test new ideas and shape public Studios 42 conversation. Committed to experimentation, Publishing 58 collaboration and advocacy, Artspaceí s mission Performance Against Goals 60 is to enhance our culture through a deeper Key Performance Indicators 76 engagement with contemporary art. Artspace Directors & Staff 80 ABOUT US Artspace Partners & Supporters 82 Artspace is an independent contemporary art space that receives public funding for its activities through the federal government through the Australia Council for the Arts and the state government through Arts NSW, and is also supported though benefaction and partnerships. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We show our respect and acknowledge the traditional owners of the land, the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation. We pay our respects to their Elders past and present and their descendants. Cover image: Emily Floyd, Art as a Verb, 2015, installation view, Artspace, Sydney. Photo: Zan Wimberley -

Daftar Produk Halal

Dunia Daging KELOMPOK DAGING DAN PRODUK DAGING OLAHAN Fronte : Vegetable Chicken Sausage, Fronte : 00010013540900 141213 Food Industries, November - Desember 2012 Beef Frankfurter, Fronte : Chicken Frankfurter, PT Nama Produk Sertifikat Exp Produsen Fronte : Blackpepper Beef Sausage Reguler, Fronte : Breakfast Beef Sausage, Fronte : Beef Frankfurter Kibif Rolade Sapi, Kibif Rolade Sapi (wet mar- Bina Mentari Skinless, Fronte : Chicken Frankfruter Skinless, Fronte : Sosis Ayam (Chicken Chipolata), Fronte : Sosis ket), Kibif Beef Salami, Kibif Daging Sapi Lada ‘00010060390212 010214 Tunggal, PT Sapi (Beef Bockwurst), Fronte : Cheesy Beef Sausage, Fronte : Blackpepper Beef Sausage, Fronte : Hitam, Kibif Sosis Sapi, Kibif Sosis Sapi Chicken Luncheon (wet market), Kibif Beef Pepperoni, Kibif Nugget Sapi, Kibif Bakso Sapi WK, Kibif Bakso Sapi WM, Kibif Dunia Daging Meat Ball Super, Kibif Bakso Halus, Kibif Beef Patties, Kibif Burger Patties Black Pepper, Kibif Beef Burger Fronte : Beef Lucheon, Fronte : Galapeno Beef 00010013540900 141213 Food Industries, Bulgogi, Kibif Burger Daging Sapi Sasage, Fronte : Roast Beef, Fronte : Beef PT Kerupuk Ikan Lele, Fish Cookies (Kerupuk 00100062720912 250914 Mina Sejahtera Coctail, Fronte : Sosis sapi Asap, Fronte : Veal Bratwurst, Fronte : Corn Beef sausage, Fronte : Garlic Beef Ikan Lele) Sausage, Fronte : Paprica Beef Sausage, Fronte : Beef Pastrami, Fronte : Beef Pepperoni, Fronte : Beef MARINADE, MRND CHICKEN STEAK , SPICY Frozen Food Salami WING , MRND SIRLOIN STEAK , SPICY WING ‘00010043750307 110414 -

For All Occasions RE:FRESH

RE:FRESH TEA for all occasions IN AGED CARE For more information, visit ufs.com ENJOY A GOOD CUPPA ANYTIME Residents always look forward to tea time. We offer you solutions for a great tea experience in any place of your facility. • In-Room/Extra Services • Lounge & Guest Area • Dining • Functions & Activities 2 in-room Whether it’s envelopes or string & tag tea bags they can prepare at their own leisure, residents can enjoy a good cup of tea without having to leave the comfort of their own room. In-Room/Extra services: Sir Thomas Lipton bulk specialty teas in a choice of black tea, green tea and herbal infusions. Available in cartons of 500s for easier refill. Lipton tea available in black and green variants with foiled envelopes to ensure a fresh cup of tea every time. Lipton Yellow Label Lipton Green Gold Envelope Envelope Tea Tea Cup Bag 500s 300s 3 Lounge & guest area Tea and a chat? Whether it may be with other residents or visiting guests, residents always look forward to tea time as a way to socialize and catch-up with each other. Premium blends for different moods and tastes Sir Thomas Lipton has an extensive range for both residents and guests to enjoy at whatever time of day and according to their preference. Sir Thomas Lipton range in 8 variants 4 dining The same way that food plays an important role in their day, tea also brings them together during meal times. Tea comes in different formats of string & tag, envelopes and pot bags, so they can have great tea moments with their meals. -

George Washington - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopediavisited on 11/13/2014

George Washington - Wikipedia, the free encyclopediavisited on 11/13/2014 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Washington From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia George Washington (February 22, 1732 [O.S. February 11, George Washington 1731][Note 1][Note 2] – December 14, 1799) was the first President of the United States (1789–1797), the Commander- in-Chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States.[3] He presided over the convention that drafted the United States Constitution, which replaced the Articles of Confederation and remains the supreme law of the land. Washington was elected president as the unanimous choice of the electors in the elections of both 1788–1789 and 1792.[4] He oversaw the creation of a strong, well-financed national government that maintained neutrality in the wars raging in Europe, suppressed rebellion, and won acceptance among Americans of all types.[5] Washington established many forms in government still used today, such as the cabinet 1st President of the United States system and inaugural address.[6][7] His retirement after two terms and the peaceful transition from his presidency to that In office of John Adams established a tradition that continued up until April 30, 1789[nb] – March 4, 1797 Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected to a third term.[8] Vice President John Adams Washington has been widely hailed as "father of his country" Preceded by Inaugural holder even during his lifetime.[3][9] Succeeded by John Adams Washington was born into the provincial gentry of Colonial Senior Officer of the Army Virginia; his wealthy planter family owned tobacco In office plantations and slaves, that he inherited.