Racial Transitions and Controversial Positions: Reply to Taylor, Gordon, Sealey, Hom, and Botts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of the Racial Identity of Children of Loving: Has Our Thinking About Race and Racial Issues Become Obsolete?

Fordham Law Review Volume 86 Issue 6 Article 12 2018 Evolution of the Racial Identity of Children of Loving: Has Our Thinking About Race and Racial Issues Become Obsolete? Kevin Brown Indiana University Maurer School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Family Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Kevin Brown, Evolution of the Racial Identity of Children of Loving: Has Our Thinking About Race and Racial Issues Become Obsolete?, 86 Fordham L. Rev. 2773 (2018). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol86/iss6/12 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVOLUTION OF THE RACIAL IDENTITY OF CHILDREN OF LOVING: HAS OUR THINKING ABOUT RACE AND RACIAL ISSUES BECOME OBSOLETE? Kevin Brown* It is a special honor for me to have this opportunity to discuss the U.S. Supreme Court’s opinion in Loving v. Virginia1 at a Symposium held in honor of its fiftieth anniversary. I served on the panel entitled “The Children of Loving,”2 which for me has two connotations. First, as an African American who married a white woman twenty years after the decision, I am a child of Loving in the sense that I was in an interracial marriage. But as a father of two black-white biracial children, I am also a father of two Loving children. -

Allegories of Gender: Transgender Autology Versus Transracialism Aniruddha Dutta

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 21:31 Atlantis Critical Studies in Gender, Culture & Social Justice Études critiques sur le genre, la culture, et la justice Allegories of Gender: Transgender Autology versus Transracialism Aniruddha Dutta Volume 39, numéro 2, 2018 Résumé de l'article This article explores how race and gender become distinguished from each URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1064075ar other in contemporary scholarly and activist debates on the comparison DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1064075ar between transracialism and transgender identities. The article argues that transracial-transgender distinctions often reinforce divides between Aller au sommaire du numéro autological (self-determined) and genealogical (inherited) aspects of subjectivity and obscure the constitution of this division through modern technologies of power. Éditeur(s) Mount Saint Vincent University ISSN 1715-0698 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Dutta, A. (2018). Allegories of Gender: Transgender Autology versus Transracialism. Atlantis, 39(2), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.7202/1064075ar All Rights Reserved © Mount Saint Vincent University, 2018 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ Special Section: Research Allegories ofGender: Transgender Autology versus Transracialism Aniruddha Dutta is an Assistant Professor in the de- Introduction: Two Scenes ofTransgender partments of Gender, Women’s and Sexuality Studies Recognition and Asian and Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Iowa. -

TDS-MAP58: Identidades Mal Entendidas. Raza Y Clase En El

traficantes de sueños Traficantes de Sueños no es una casa editorial, ni si- quiera una editorial independiente que contempla la publicación de una colección variable de textos crí- ticos. Es, por el contrario, un proyecto, en el sentido estricto de «apuesta», que se dirige a cartografiar las líneas constituyentes de otras formas de vida. La cons- trucción teórica y práctica de la caja de herramientas que, con palabras propias, puede componer el ciclo de luchas de las próximas décadas. Sin complacencias con la arcaica sacralidad del libro, sin concesiones con el narcisismo literario, sin lealtad alguna a los usurpadores del saber, TdS adopta sin ambages la libertad de acceso al conocimiento. Queda, por tanto, permitida y abierta la reproducción total o parcial de los textos publicados, en cualquier formato imaginable, salvo por explícita voluntad del autor o de la autora y sólo en el caso de las ediciones con ánimo de lucro. Omnia sunt communia! mapas 58 Mapas. Cartas para orientarse en la geografía variable de la nueva composición del trabajo, de la movilidad entre fron- teras, de las transformaciones urbanas. Mutaciones veloces que exigen la introducción de líneas de fuerza a través de las discusiones de mayor potencia en el horizonte global. Mapas recoge y traduce algunos ensayos, que con lucidez y una gran fuerza expresiva han sabido reconocer las posibili- dades políticas contenidas en el relieve sinuoso y controver- tido de los nuevos planos de la existencia. © 2018, Asad Haider © 2020, de esta edición, Traficantes de Sueños creative cc commons Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivadas 3.0 España (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) Usted es libre de: * Compartir - copiar, distribuir, ejecutar y comunicar públicamente la obra Bajo las condiciones siguientes: * Reconocimiento — Debe reconocer los créditos de la obra de la manera especificada por el autor o el licenciante (pero no de una manera que sugiera que tiene su apoyo o que apoyan el uso que hace de su obra). -

Rachel Dolezal and the “Gotcha” Tactic Used to Distract Blacks Analysis by Sandra Williams Be Defined As Pointing out the Wrong Way

NAACP Update: Denise Osei: Juneteenth 2015: Our Voices: IN THIS Naima Quarles-Burnley A Life and Career 150 Year Anniversary A Right Cross and is New President Serving Others of the End of Slavery a Left Hook ISSUE Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Page 13 July 2015 www.blacklensnews.com Vol. 1 Issue No. 7 Spokane’s Black Community News Source A Not So Little Lesson In MISDIRECTIONRachel Dolezal And The “Gotcha” Tactic Used To Distract Blacks Analysis by Sandra Williams be defined as pointing out the wrong way. Another way of defining misdirection is by Based on the unprecedented level of fury focusing on its function. Any magic effect and international “outrage” that was as- (what the spectator sees) requires a method sociated with the discovery that Rachel (the method used to produce the effect). Dolezal, the former Spokane NAACP President, was in fact a “white imposter”, The main purpose of misdirection is to as some people called her, you would have disguise the method and thus prevent thought that she was responsible for pull- the audience from detecting the method ing out her service revolver and emptying whilst still experiencing the effect.” eight bullets into the back of an unarmed, In other words, doing something to distract fleeing black man. No wait, that wasn’t her. people so that they don’t notice what is ac- Well, if she didn’t murder anybody, she tually happening. must be the one to blame for the dispropor- If it wasn’t such a painful thing to watch, tionate rates of Black people that are be- it would have been fascinating to observe ing arrested and incarcerated in a criminal the degree to which our community got “justice” system that actually profits off of caught up in the “importance” of Rachel’s the point of declaring that Rachel Dolezal I had no idea at the time how profound that those arrests and incarcerations. -

Essence and Existence in William Faulkner's “A Rose for Emily” And

Syrian Arab Republic University of Aleppo Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of English Essence and Existence in William Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily” and The Sound and the Fury and in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind By Nour E. Dawalibi Supervisor Prof. Dr. Muhammad Al-Taha Submitted to the University of Aleppo in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English 2016 Essence and Existence in William Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily” and The Sound and the Fury and in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind By Nour E. Dawalibi Supervisor Prof. Dr. Muhammad Al-Taha Dawalibi i Table of Contents Dedication ii Acknowledgments iii Abstract iv Introduction 1 Chapter One Essence and Existence: Humanism and Existentialism 11 Chapter Two Essence and Existence in William Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily” 39 Chapter Three Essence and Existence in William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury 60 Chapter Four Essence and Existence in Margret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind 84 Conclusion 105 Works Cited 111 Works Consulted 125 Dawalibi ii Dedication For my loving, caring and compassionate parents and for my sweet heart Dania Dawalibi iii Acknowledgments In the process of doing the research and the writing of this dissertation, I have accumulated many debts that can never be repaid. No one deserves more credit for this study than Professor Muhammad Al-Taha and Professor Iman Lababidi who have given me great motivation and were always ready to give help and support whenever needed. They were more than generous in their expertise and their precious time. -

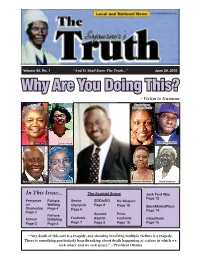

Why Are You Doing This? - Victim to Gunman

Volume 34, No. 1 “And Ye Shall Know The Truth...” June 24, 2015 Why Are You Doing This? - Victim to Gunman Rev. DePayne Middleton-Doctor Ethel Lance Cynthia Hurd Tywanza Sanders Rev. Daniel Simmons Myra Thompson Rev. Clementa Pinckney Sharonda Singleton Susie Jackson In This Issue... The Soulcial Scene Jack Ford Way Page 12 Perryman Fathers Senior ZOOtoDO No Weapon on Walking Olympics Page 8 Page 10 BlackMarketPlace Charleston Page 4 Page 6 Page 14 Page 2 Fathers Second Price Tolliver Dribbling Festivals Baptist Fashions Classifieds Page 3 Page 5 Page 7 Page 9 Page 16 Page 15 “Any death of this sort is a tragedy, any shooting involving multiple victims is a tragedy. There is something particularly heartbreaking about death happening at a place in which we seek solace and we seek peace.” - President Obama Page 2 The Sojourner’s Truth June 24, 2015 Jesus and Violence Dr. Donald L. Perryman – By Rev. Donald L. Perryman, D.Min. The Truth Contributor Father to his Daughters, ...The tensions which we witness in the world Father to the Community today are indicative of the fact that a new By Tracee Perryman Guest Column world is being born and an old world is pass- Dr. Donald L. Perryman has been a mentor ing away. and father-figure to so many in the church, -- Martin Luther King, Jr. in “The Birth of a New Age” and in the community. Today, I want to focus on the father he was at home. Father/daugh- ter relationships are very complex. Fathers The Christian commands to “Love your en- parent very differently from mothers. -

Immanence, Abjection and Transcendence Through Satī/Śakti in Prabha Khaitan’S Autobiography Anyā Se Ananyā

Cracow Indological Studies Vol. XX, No. 2 (2018), pp. 231–256 https://doi.org/10.12797/CIS.20.2018.02.11 Alessandra Consolaro (University of Turin) [email protected] Immanence, Abjection and Transcendence through Satī/Śakti in Prabha Khaitan’s Autobiography Anyā se ananyā SUMMARY: This article aims to explore embodiment as articulated in Prabha Khaitan’s autobiography Anyā se ananyā, inscribing it in a philosophical journey that refuses the dichotomy between Western and Indian thought. Best known as the writer who introduced French feminist existentialism to Hindi-speaking readers through her translation of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, Prabha Khaitan is positioned as a Marwari woman, intellectual, successful businesswoman, poet, novelist, and feminist, which makes her a cosmopolitan figure. In this article I use three analytical tools: the existentialist concepts of ‘immanence’ and ‘transcendence’—as differently proposed by Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir; Julia Kristeva’s definition of ‘abjection’—what does not ‘respect borders, positions, rules’ and ‘disturbs iden- tity, system, order;’ and the satī/śakti notion—both as a venerated (tantric) ritual which gains its sanction from the scriptures, and as a practice written into the history of the Rajputs, crucial to the cultural politics of Calcutta Marwaris, who have been among the most vehement defenders of the satī worship in recent decades. KEYWORDS: Prabha Khaitan, autobiography, abjection, transcendence, satī, śakti, embodiment 1. Introduction This article aims to analyze Prabha Khaitan’s1 autobiography Anyā se ananyā (“From the Other One to the Only One,” Khetān 2007 [henceforth ASA]) 1 Prabhā Khetān (1942–2008). -

Simone De Beauvoir

Simone De Beauvoir Rahul Varma & Chloe Son 1908-1986 Paris, France Catholic → Atheist Sorbonne University Death of Zaza Unconventional Relationship w/ Sartre The Second Sex Published 1949; Index of Prohibited Books Rejects Biological Explanations of Secondary Status 1. Economic Independence 2. Birth Control 3. Abortion 4. Child Care Oppression as Man’s “Other” “One is not born but becomes a woman.” Laid groundwork for movement Second Wave Male-centric ideology Feminism Enforced by: 1. Myths Sexuality | Family | Workplace 2. Pregnancy 3. Lactating Reproductive rights | De facto inequalities 4. Menstruation Official legal inequalities Influence on Betty Friedan Starting point: Emphasizes: experiences of Freedom; interpersonal individual relationships; experience of living as human body Feminist Existentialism Subject = men “Authenticity” Object = women Opposed to “woman belongs at home” Contributions to: Woman’s implicit inferiority Feminist Theory Central to feminism: 1. Systematic subordination 2. Surrendering to system → bad faith 3. Bad faith → lack of “authenticity” “Science regards any characteristic as a reaction dependent in part upon a situation.” 1921 - 2006 The Feminine Mystique Share existentialism | different contexts Called for system-friendly reforms: 1. Ideas 2. Culture 3. Education Core differences with Beauvoir: Betty Friedan American feminist Empowerment → white, American, middle class Female → dominating group Individualist/Reformist vs Socialistic/Radical 1934 - Sept. 6 2017 Femininity & womanhood ≠ biological Wrote Sexual Politics : “interior colonization” Called for: Kate Millett 1. Extreme reorganization of society 2. Eradication of patriarchy American lesbian feminist Supported gay liberation Discussion Questions 1. How do you think Simone de Beauvoir's harsh critique of misogynistic biblical texts affected her impact as a feminist leader? How might religious interaction with the feminist movement be different during this period and today? 2. -

Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements Amanda Huminski The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2826 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPERIMENTAL PHILOSOPHY AND FEMINIST EPISTEMOLOGY: CONFLICTS AND COMPLEMENTS by AMANDA HUMINSKI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 AMANDA HUMINSKI All Rights Reserved ii Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements By Amanda Huminski This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________ ________________________________________________ Date Linda Martín Alcoff Chair of Examining Committee _______________________________ ________________________________________________ Date Nickolas Pappas Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Jesse Prinz Miranda Fricker THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements by Amanda Huminski Advisor: Jesse Prinz The recent turn toward experimental philosophy, particularly in ethics and epistemology, might appear to be supported by feminist epistemology, insofar as experimental philosophy signifies a break from the tradition of primarily white, middle-class men attempting to draw universal claims from within the limits of their own experience and research. -

Melissa M. Kozma Curriculum Vitae November 19, 2019

Melissa M. Kozma Curriculum Vitae November 19, 2019 UW-Eau Claire - Barron County 1800 College Drive Meggers Hall 134 Rice Lake, WI 54868 715.788.6268 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT 2011 – Present Senior Lecturer, Philosophy and Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire – Barron County 2006 - 2011 Associate Lecturer, Philosophy and Women’s Studies University of Wisconsin – Barron County 1997- 2005 Teaching Assistant, Department of Philosophy, University of Illinois at Chicago EDUCATION 2010 Ph.D., Philosophy, University of Illinois at Chicago 1999 M.A., Philosophy, University of Illinois at Chicago 1993 B.A., English, Columbia College Chicago AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Feminist Philosophy, Feminist Ethics, Ethics, Feminist Political Theory, Social and Political Philosophy AREAS OF COMPETENCE Philosophy of Race, Existentialism PUBLICATIONS 2017 “For the Love of the Feminist Killjoy: Solving Philosophy’s Woman White Male Problem”, co-authored with Jeanine Weekes Schroer (University of Minnesota - Duluth), in Surviving Sexism in Academia: Strategies for Feminist Leadership, Kirsti Cole and Holly Hassel, editors, Routledge Press. 2014 “Purposeful Nonsense, Intersectionality, and the Mission to Save Black Babies”, co- authored with Jeanine Weekes Schroer (University of Minnesota - Duluth), in Why Race and Gender Still Matter: An Intersectional Approach. Gotswami, O’Donovan, and Yount, editors, Pickering and Chatto. CONFERENCE PARTICIPATION Invited Talks 2014 Participant in roundtable discussion of the book Why Race -

By: Alexa Mcmunagle March 4, 2020

CROSSING RACIALIZED LINES: Mapping Academics’ Responses To So-Called “Transracialism” This research was supported by the Jamie Cassels Undergraduate Research Awards, University of Victoria. Supervised by Dr. Sikata Banerjee. Department of Gender Studies. By: Alexa McMunagle March 4, 2020. Introduction Debates White Privilege o ease of transition In 2017, a young Canadian academic by the name of Rebecca Tuvel o “Transracialism” within feminist philosophy o whites passing for black is more accessible & easily reversible than blacks published an article in Hypatia entitled “In Defense of Transracialism” in o Janice Raymond, an anti-trans feminist, coined the term “transracial” in 1979 as passing for white (Tuvel, 2017, p. 270) which she reflects on the differential ways in which Caitlyn Jenner and part of a rhetorical question that intended to disparage gender confirmation Ø In response, Tuvel argues that similar to “FtM privilege”, white to black Rachel Dolezal were received by the media and broader public. Tuvel surgeries by likening them to a hypothetical “transracial” surgery (Hom, p. 33) transition privilege should be of “minor relevance” to ethics. Instead, we argues that “considerations that support transgenderism seem to apply o Christine Overall, a Canadian philosopher, took up Raymond’s hypothetical in should ensure equal access to resources for transitioning (2017, p. 271) equally to transracialism” (2017, p. 263). 2004 and argued that if transsexualism and the providing of “medical and social Ø In response to Tuvel, Sealey argues that such resources aren’t available resources” towards transitions is “morally acceptable”, then the same should be right now, ∴ white people have an unequal range of agency (p. -

Understanding Experiences of Canadian Women in Building and Construction Trades Through a Feminist Existential Lens

“A Labyrinth of Snake Pits and Traps at Every Corner”: Understanding Experiences of Canadian Women in Building and Construction Trades Through a Feminist Existential Lens By Rhonda L. Dever A Dissertation Submitted to Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration (Management) April, 2021, Halifax, Nova Scotia Copyright Rhonda L. Dever, 2021 Approved: Dr. Albert Mills, Supervisor Saint Mary’s University, Halifax Approved: Scott MacMillan, Committee Member Mount Saint Vincent University, Halifax Approved: Dr. Meredith Ralston, Committee Member Mount Saint Vincent University, Halifax Approved: Dr. Martin Parker, External Examiner University of Bristol, Bristol Date: April 19, 2021 Abstract “A Labyrinth of Snake Pits and Traps at Every Corner”: Understanding Experiences of Canadian Women in Building and Construction Trades Through a Feminist Existential Lens By Rhonda L. Dever Abstract: By 2010, women made up almost half (47%) of the entire Canadian workforce (Ferraro, 2010) and the majority of women work in the service sector with the highest concentration (82%) in the healthcare and social assistance sectors. While the number of women in the workforce has been increasing, there has not been an increase in the number of women in the building trades despite initiatives that have been steadily encouraging women to pursue careers in trades as a viable option to earn a living. The stories of ten female tradespeople were examined using narrative analysis (Riessman, 2008) through a feminist existential lens using the work of de Beauvoir (1976, 1989). Women choosing to pursue a career in trades face much different consequences for their choice than their male counterparts.