Roundleaf Toothcup [Rotala Rotundifolia (Roxb.) Koehne] Gary N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

27April12acquatic Plants

International Plant Protection Convention Protecting the world’s plant resources from pests 01 2012 ENG Aquatic plants their uses and risks Implementation Review and Support System Support and Review Implementation A review of the global status of aquatic plants Aquatic plants their uses and risks A review of the global status of aquatic plants Ryan M. Wersal, Ph.D. & John D. Madsen, Ph.D. i The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of speciic companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.All rights reserved. FAO encourages reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Ofice of Knowledge Exchange, -

Chapter 6 ENUMERATION

Chapter 6 ENUMERATION . ENUMERATION The spermatophytic plants with their accepted names as per The Plant List [http://www.theplantlist.org/ ], through proper taxonomic treatments of recorded species and infra-specific taxa, collected from Gorumara National Park has been arranged in compliance with the presently accepted APG-III (Chase & Reveal, 2009) system of classification. Further, for better convenience the presentation of each species in the enumeration the genera and species under the families are arranged in alphabetical order. In case of Gymnosperms, four families with their genera and species also arranged in alphabetical order. The following sequence of enumeration is taken into consideration while enumerating each identified plants. (a) Accepted name, (b) Basionym if any, (c) Synonyms if any, (d) Homonym if any, (e) Vernacular name if any, (f) Description, (g) Flowering and fruiting periods, (h) Specimen cited, (i) Local distribution, and (j) General distribution. Each individual taxon is being treated here with the protologue at first along with the author citation and then referring the available important references for overall and/or adjacent floras and taxonomic treatments. Mentioned below is the list of important books, selected scientific journals, papers, newsletters and periodicals those have been referred during the citation of references. Chronicles of literature of reference: Names of the important books referred: Beng. Pl. : Bengal Plants En. Fl .Pl. Nepal : An Enumeration of the Flowering Plants of Nepal Fasc.Fl.India : Fascicles of Flora of India Fl.Brit.India : The Flora of British India Fl.Bhutan : Flora of Bhutan Fl.E.Him. : Flora of Eastern Himalaya Fl.India : Flora of India Fl Indi. -

Plant Name Common Name Description Variety Variegated Green and Creamy Iris Blade-Like Foliage

GLENBOGAL AQUATIC PLANT LIST Plant Name Common Name Description Variety Variegated green and creamy iris blade-like foliage. Sweet flag tolerates Acorus Calamus shade and is frost hardy. Compact growing habit. Height: 60 to 90cms. Sweet flag Variegatus Prefers moist soil but will tolerate up to 15cms of water above the crown. Stunning purple/blue iris-like flowers early in the season. Marginal Sea This green version of the Acorus family has deep green foliage. It tolerates shade and is evergreen in many climates. Fantastic for Green Japanese Acorus Gramineus Green keeping colour all winter. Height: up to 30cms Plant spread: Restricted Rush by basket size Depth: moist soil to approx. 10cms (will grow in deeper water but may not do as well) Marginal A Ogon has light green foliage accented with bright yellow stripes. It tolerates shade and is evergreen in many climates. Height: up to 30cms Acorus Gramineus Ogon Gold Japanese Rush Plant spread: Restricted by basket size Depth: moist soil to approx. 20cms (can grow in deeper water if required) Great plant to remove excess nutrient. Marginal A Light green foliage accented with white stripes. Tolerates shade and is evergreen in many climates. Variegatus is fantastic for keeping colour all Acorus Gramineus winter. Height: up to 30cms - Plant spread: Restricted by basket size Variegatus Depth: moist soil to approx. 20cms (can grow in deeper water if required) Good plant to remove excess nutrient. Marginal A A low growing plant with dainty purple frilly leaves and deep blue spikes that flower in spring and early summer. Prefers semi shade. -

Study of Vessel Elements in the Stem of Genus Ammannia and Rotala (Lytharaceae)

Science Research Reporter 2(1):59-65, March 2012 ISSN: 2249-2321 (Print) Study of Vessel elements in the stem of Genus Ammannia and Rotala (Lytharaceae) Anil A Kshirsagar and N P Vaikos Department of Botany, Shivaji Arts, Commerce and Science College Kannad Dist- Aurangabad. (M.S.) 431103 Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University Aurangabad [email protected] ABSTRACT The vessel elements in the stem of Genus Ammannia with four species and the Genus Rotala with nine species have been investigated. The vessel elements in the stem of Ammannia and Rotala exhibit the variation in their length and diameter. The minimum length of vessel element was reported in species of Rotala indica and Rotala rosea 142.8µm, while the maximum length of vessel element was reported in Ammannia baccifera sub spp.aegyptiaca (571.2 µm). The minimum diameter of vessel element was recorded in Rotala floribunda, R.occultiflora, R. rotundifolia, R.malmpuzhensis (21.4 µm) while maximum diameter of vessel element was recorded in Ammannia baccifera sub spp.baccifera (49.98 µm). The perforation plates were mostly simple. The positions of perforation plate were terminal and sub-terminal, the tails were recorded in many investigated taxa and the lateral walls of vessels were pitted. The vestured pits were the characteristics of family-Lytheraceae. Keywords: Vessel elements, perforation plates, Stem of Genus Ammannia and Rotala (Lythraceae) INTRODUCTION The family Lythraceae consists of about 24 genera kinwat and fixed in FAA.They were preserved in 70% and nearly 500 species widespread in the tropical alcohol. The stem macerated in 1:1 proportion of countries with relatively few species in the 10% Nitric acid and 10% Chromic acid solution and temperate regions (Cronquist,1981) In India it is then the materials were washed thoroughly in represented by 11 genera and about 45 species water, stained in 1% safranin and mounts in glycerin. -

Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Dark Septate Fungi in Plants Associated with Aquatic Environments Doi: 10.1590/0102-33062016Abb0296

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and dark septate fungi in plants associated with aquatic environments doi: 10.1590/0102-33062016abb0296 Table S1. Presence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and/or dark septate fungi (DSF) in non-flowering plants and angiosperms, according to data from 62 papers. A: arbuscule; V: vesicle; H: intraradical hyphae; % COL: percentage of colonization. MYCORRHIZAL SPECIES AMF STRUCTURES % AMF COL AMF REFERENCES DSF DSF REFERENCES LYCOPODIOPHYTA1 Isoetales Isoetaceae Isoetes coromandelina L. A, V, H 43 38; 39 Isoetes echinospora Durieu A, V, H 1.9-14.5 50 + 50 Isoetes kirkii A. Braun not informed not informed 13 Isoetes lacustris L.* A, V, H 25-50 50; 61 + 50 Lycopodiales Lycopodiaceae Lycopodiella inundata (L.) Holub A, V 0-18 22 + 22 MONILOPHYTA2 Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense L. A, V 2-28 15; 19; 52; 60 + 60 Osmundales Osmundaceae Osmunda cinnamomea L. A, V 10 14 Salviniales Marsileaceae Marsilea quadrifolia L.* V, H not informed 19;38 Salviniaceae Azolla pinnata R. Br.* not informed not informed 19 Salvinia cucullata Roxb* not informed 21 4; 19 Salvinia natans Pursh V, H not informed 38 Polipodiales Dryopteridaceae Polystichum lepidocaulon (Hook.) J. Sm. A, V not informed 30 Davalliaceae Davallia mariesii T. Moore ex Baker A not informed 30 Onocleaceae Matteuccia struthiopteris (L.) Tod. A not informed 30 Onoclea sensibilis L. A, V 10-70 14; 60 + 60 Pteridaceae Acrostichum aureum L. A, V, H 27-69 42; 55 Adiantum pedatum L. A not informed 30 Aleuritopteris argentea (S. G. Gmel) Fée A, V not informed 30 Pteris cretica L. A not informed 30 Pteris multifida Poir. -

Risk Assessment for Invasiveness Differs for Aquatic and Terrestrial Plant Species

Biol Invasions DOI 10.1007/s10530-011-0002-2 ORIGINAL PAPER Risk assessment for invasiveness differs for aquatic and terrestrial plant species Doria R. Gordon • Crysta A. Gantz Received: 10 November 2010 / Accepted: 16 April 2011 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011 Abstract Predictive tools for preventing introduc- non-invaders and invaders would require an increase tion of new species with high probability of becoming in the threshold score from the standard of 6 for this invasive in the U.S. must effectively distinguish non- system to 19. That higher threshold resulted in invasive from invasive species. The Australian Weed accurate identification of 89% of the non-invaders Risk Assessment system (WRA) has been demon- and over 75% of the major invaders. Either further strated to meet this requirement for terrestrial vascu- testing for definition of the optimal threshold or a lar plants. However, this system weights aquatic separate screening system will be necessary for plants heavily toward the conclusion of invasiveness. accurately predicting which freshwater aquatic plants We evaluated the accuracy of the WRA for 149 non- are high risks for becoming invasive. native aquatic species in the U.S., of which 33 are major invaders, 32 are minor invaders and 84 are Keywords Aquatic plants Á Australian Weed Risk non-invaders. The WRA predicted that all of the Assessment Á Invasive Á Prevention major invaders would be invasive, but also predicted that 83% of the non-invaders would be invasive. Only 1% of the non-invaders were correctly identified and Introduction 16% needed further evaluation. The resulting overall accuracy was 33%, dominated by scores for invaders. -

Rotala Dhaneshiana, a New Species of Lythraceae from India

Phytotaxa 188 (4): 227–232 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.188.4.5 Rotala dhaneshiana, a new species of Lythraceae from India M. K. RATHEESH NARAYANAN1, C. N. SUNIL2, T. SHAJU3, M. K. NANDAKUMAR4, M. SIVADASAN5,6 & A. H. ALFARHAN5 1Department of Botany, Payyanur College, Edat P.O., Payyanur, Kannur – 670 327, Kerala, India. 2Department of Botany, S.N.M .College, Moothakunnam, Maliankrara P.O., Ernakulam – 683 516, Kerala, India. 3Tropical Botanic Garden and Research Institute, Palode P.O., Thiruvananthapuram – 695 562, Kerala, India. 4Community Agrobiodiversity Centre, M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Puthoorvayal, Kalpetta, Wayanad – 673 121, Kerala, India. 5Department of Botany & Microbiology, College of Science, King Saud University, P. O. Box 2455, Riyadh –11451, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 6Corresponding author: email: [email protected] Abstract Rotala dhaneshiana, a new species of Lythraceae collected from a semi-marshy area of Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary in Kerala, India is described and illustrated. It is closely allied to R. malampuzhensis usually in having trimerous flowers, but differs in having 4-angled, narrowly winged stems, long epicalyx lobes alternating with sepals, obovate-apiculate petals, and absence of nectar scales. It resembles R. juniperina, an African species in having trimerous flowers but differs in having sessile, decurrent-based leaves and sessile pistil. Key words: Endemic species, Kerala, Myrtales, Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary Introduction The genus Rotala Linnaeus (1771: 143, 175) (Lythraceae) has tropical and subtropical distribution and is represented by more than 50 species of aquatic or amphibious plants. -

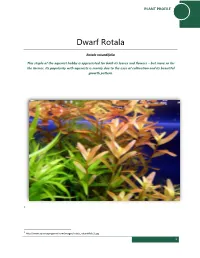

Dwarf Rotala

PLANT PROFILE Dwarf Rotala Rotala rotundifolia This staple of the aquarist hobby is appreciated for both its leaves and flowers – but more so for the former. Its popularity with aquarists is mainly due to the ease of cultivation and its beautiful growth pattern. 1 1 http://www.aquascapingworld.com/images/rotala_rotundifolia2.jpg 1 PLANT PROFILE which lasts to this date, thus creating possible FACT SHEET mistakes, as the true Rotala indica was also Scientific name: introduced to the hobby several years ago. The Rotala rotundifolia differences in the inflorescence provide the key Common name: to proper identification. Dwarf Rotala Family: Lythraceae Description Native distribution: Indo-China, Vietnam, Burma (Myanmar) Rotala rotundifolia is a creeping aquatic Height: perennial species with soft stems that often 20 – 80 cm branch to form low, creeping clumps. R Width: 2 – 4 cm rotundifolia has both submersed (underwater) Growth rate: and emergent (out-of-water) forms, which Fast differ in a number of ways. While both forms pH: have small leaves – less than 2.5cm long, 6.8 – 7.2 Hardness: arranged in groups of two or three around 0 – 21°dKH / 2 – 30°dGH plants’ pink stems – the emergent form has Temperature: fleshy, bright-green and rounded leaves, while 18°C – 30°C in the aquarium they grow to a longer, Lighting needs: Medium to high narrower form which has darker green or Aquarium placement: reddish leaves that are thin and lanceolate Middle to background (sword-shaped). Rotala rotundifolia (also known in aquarist circles as Dwarf Rotala, Pink Baby Tears, Round Leaf Toothcup and Pink Rotala), has been a popular aquarium plant for decades. -

Journalofthreatenedtaxa

OPEN ACCESS The Journal of Threatened Taxa fs dedfcated to bufldfng evfdence for conservafon globally by publfshfng peer-revfewed arfcles onlfne every month at a reasonably rapfd rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org . All arfcles publfshed fn JoTT are regfstered under Creafve Commons Atrfbufon 4.0 Internafonal Lfcense unless otherwfse menfoned. JoTT allows unrestrfcted use of arfcles fn any medfum, reproducfon, and dfstrfbufon by provfdfng adequate credft to the authors and the source of publfcafon. Journal of Threatened Taxa Bufldfng evfdence for conservafon globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Onlfne) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Prfnt) Artfcle Florfstfc dfversfty of Bhfmashankar Wfldlffe Sanctuary, northern Western Ghats, Maharashtra, Indfa Savfta Sanjaykumar Rahangdale & Sanjaykumar Ramlal Rahangdale 26 August 2017 | Vol. 9| No. 8 | Pp. 10493–10527 10.11609/jot. 3074 .9. 8. 10493-10527 For Focus, Scope, Afms, Polfcfes and Gufdelfnes vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/About_JoTT For Arfcle Submfssfon Gufdelfnes vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/Submfssfon_Gufdelfnes For Polfcfes agafnst Scfenffc Mfsconduct vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/JoTT_Polfcy_agafnst_Scfenffc_Mfsconduct For reprfnts contact <[email protected]> Publfsher/Host Partner Threatened Taxa Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 August 2017 | 9(8): 10493–10527 Article Floristic diversity of Bhimashankar Wildlife Sanctuary, northern Western Ghats, Maharashtra, India Savita Sanjaykumar Rahangdale 1 & Sanjaykumar Ramlal Rahangdale2 ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) 1 Department of Botany, B.J. Arts, Commerce & Science College, Ale, Pune District, Maharashtra 412411, India 2 Department of Botany, A.W. Arts, Science & Commerce College, Otur, Pune District, Maharashtra 412409, India OPEN ACCESS 1 [email protected], 2 [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: Bhimashankar Wildlife Sanctuary (BWS) is located on the crestline of the northern Western Ghats in Pune and Thane districts in Maharashtra State. -

Ecological Checklist of the Missouri Flora for Floristic Quality Assessment

Ladd, D. and J.R. Thomas. 2015. Ecological checklist of the Missouri flora for Floristic Quality Assessment. Phytoneuron 2015-12: 1–274. Published 12 February 2015. ISSN 2153 733X ECOLOGICAL CHECKLIST OF THE MISSOURI FLORA FOR FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT DOUGLAS LADD The Nature Conservancy 2800 S. Brentwood Blvd. St. Louis, Missouri 63144 [email protected] JUSTIN R. THOMAS Institute of Botanical Training, LLC 111 County Road 3260 Salem, Missouri 65560 [email protected] ABSTRACT An annotated checklist of the 2,961 vascular taxa comprising the flora of Missouri is presented, with conservatism rankings for Floristic Quality Assessment. The list also provides standardized acronyms for each taxon and information on nativity, physiognomy, and wetness ratings. Annotated comments for selected taxa provide taxonomic, floristic, and ecological information, particularly for taxa not recognized in recent treatments of the Missouri flora. Synonymy crosswalks are provided for three references commonly used in Missouri. A discussion of the concept and application of Floristic Quality Assessment is presented. To accurately reflect ecological and taxonomic relationships, new combinations are validated for two distinct taxa, Dichanthelium ashei and D. werneri , and problems in application of infraspecific taxon names within Quercus shumardii are clarified. CONTENTS Introduction Species conservatism and floristic quality Application of Floristic Quality Assessment Checklist: Rationale and methods Nomenclature and taxonomic concepts Synonymy Acronyms Physiognomy, nativity, and wetness Summary of the Missouri flora Conclusion Annotated comments for checklist taxa Acknowledgements Literature Cited Ecological checklist of the Missouri flora Table 1. C values, physiognomy, and common names Table 2. Synonymy crosswalk Table 3. Wetness ratings and plant families INTRODUCTION This list was developed as part of a revised and expanded system for Floristic Quality Assessment (FQA) in Missouri. -

Rotala Species in Peninsular India, Where Ir Displays Maximum Morphological Diversity Than in Other Parts of the Subcontinent

Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. (Plant Sci.), Vol. 99, No. 3, June 1989, pp. 179-197. Printed in India. RotMa Linn. (Lythraceae) in peninsular India K T JOSEPH and V V SIVARAJAN Department of Botany, University of Calicut, Calicut 673 635, India MS received 21 June 1988; revised 17 February 1989 Abstraet. This paper deals with a revised taxonomic study of Rotala species in peninsular India, where ir displays maximum morphological diversity than in other parts of the subcontinent. Of the 19 species reported from India, 14 are distributed here. Besides, two new species of the genus, Rotala cook¡ Joseph and Sivarajan and Rotala vasudevanii Joseph and Sivarajan have also been discovered and described from this part of the country, making the total number of species 16. Ah artificial key for the species, their nomenclature and synonymy, descriptions and other relevant notes are provided here. Keywords. Lythraceae; Rotala; Ammannia. 1. Introduction The genera Ammannia Linn. (1753) and Rotala Linn. (1771) are closely allied with a remarkable degree of similarity in habit often leading to confusion in their generic recognition. Earlier authors considered Ammannia as a larger, more inclusive taxon, including Rotala in it. Bentham and Hooker (1865) recognised two subgenera in Ammannia viz., Subg. Rotala and Subg. Eu-Ammannia and this was followed by Clarke (1879) in his account of Indian species of this group for Hooker's Flora of British India. However, the current consensus among botanists is in favour of treating them as distinct genera, based mainly on the dehiscence of the fruits and structure of the pericarp (see van Leeuwen 1971; Panigrahi 1976).