SERVICE (Aerospace Corp.', ,E'" Eduna-P AIR Clif.) 100. P HC A05/9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

G410020002/A N/A Client Ref

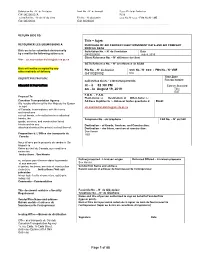

Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amd. No. - N° de la modif. Buyer ID - Id de l'acheteur G410020002/A N/A Client Ref. No. - N° de réf. du client File No. - N° du dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME G410020002 G410020002 RETURN BIDS TO: Title – Sujet: RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: PURCHASE OF AIR CARRIER FLIGHT MOVEMENT DATA AND AIR COMPANY PROFILE DATA Bids are to be submitted electronically Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date by e-mail to the following addresses: G410020002 July 8, 2019 Client Reference No. – N° référence du client Attn : [email protected] GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG Bids will not be accepted by any File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME other methods of delivery. G410020002 N/A Time Zone REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Sollicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Fuseau horaire DEMANDE DE PROPOSITION at – à 02 :00 PM Eastern Standard on – le August 19, 2019 Time EST F.O.B. - F.A.B. Proposal To: Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Canadian Transportation Agency Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions à: Email: We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in right [email protected] of Canada, in accordance with the terms and conditions set out herein, referred to herein or attached hereto, the Telephone No. –de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

July/August 2000 Volume 26, No

Irfc/I0 vfa£ /1 \ 4* Limited Edition Collectables/Role Model Calendars at home or in the office - these photo montages make a statement about who we are and what we can be... 2000 1999 Cmdr. Patricia L. Beckman Willa Brown Marcia Buckingham Jerrie Cobb Lt. Col. Eileen M. Collins Amelia Earhart Wally Funk julie Mikula Maj. lacquelyn S. Parker Harriet Quimby Bobbi Trout Captain Emily Howell Warner Lt. Col. Betty Jane Williams, Ret. 2000 Barbara McConnell Barrett Colonel Eileen M. Collins Jacqueline "lackie" Cochran Vicky Doering Anne Morrow Lindbergh Elizabeth Matarese Col. Sally D. Woolfolk Murphy Terry London Rinehart Jacqueline L. “lacque" Smith Patty Wagstaff Florene Miller Watson Fay Cillis Wells While They Last! Ship to: QUANTITY Name _ Women in Aviation 1999 ($12.50 each) ___________ Address Women in Aviation 2000 $12.50 each) ___________ Tax (CA Residents add 8.25%) ___________ Shipping/Handling ($4 each) ___________ City ________________________________________________ T O TA L ___________ S ta te ___________________________________________ Zip Make Checks Payable to: Aviation Archives Phone _______________________________Email_______ 2464 El Camino Real, #99, Santa Clara, CA 95051 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL WOMEN PILOTS (ISSN 0273-608X) 99 NEWS INTERNATIONAL Published by THE NINETV-NINES* INC. International Organization of Women Pilots A Delaware Nonprofit Corporation Organized November 2, 1929 WOMEN PILOTS INTERNATIONAL HEADQUARTERS Box 965, 7100 Terminal Drive OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OFTHE NINETY-NINES® INC. Oklahoma City, -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

The Port of Portland

NEW ISSUE—BOOK ENTRY ONLY RATING: SEE “RATING” In the opinion of Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP, Bond Counsel, based upon an analysis of existing laws, regulations, rulings and court decisions and assuming, among other matters, the accuracy of certain representations and compliance with certain covenants, interest on the Series Twenty-Four Bonds is excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes under Section 103 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, except that no opinion is expressed as to the status of interest on any Series Twenty-Four B Bond for any period that such Series Twenty-Four B Bond is held by a “substantial user” of the facilities financed or refinanced by the Series Twenty-Four B Bonds or by a “related person” within the meaning Section 147(a) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986. Bond Counsel observes that interest on the Series Twenty-Four B Bonds is a specific preference item for purposes of the federal individual and corporate alternative minimum taxes. In the further opinion of Bond Counsel, interest on the Series Twenty-Four A Bonds is not a specific preference item for purposes of the federal individual and corporate alternative minimum taxes, although Bond Counsel observes that such interest is included in adjusted current earnings when calculating corporate alternative minimum taxable income. Bond Counsel also is of the opinion based upon existing laws of the State of Oregon interest on the Series Twenty-Four Bonds is exempt from personal income taxation by the State of Oregon. Bond Counsel expresses no opinion regarding any other tax consequences related to the ownership or disposition of, or the accrual or receipt of interest on, the Series Twenty-Four Bonds. -

Bankruptcy Tilts Playing Field Frank Boroch, CFA 212 272-6335 [email protected]

Equity Research Airlines / Rated: Market Underweight September 15, 2005 Research Analyst(s): David Strine 212 272-7869 [email protected] Bankruptcy tilts playing field Frank Boroch, CFA 212 272-6335 [email protected] Key Points *** TWIN BANKRUPTCY FILINGS TILT PLAYING FIELD. NWAC and DAL filed for Chapter 11 protection yesterday, becoming the 20 and 21st airlines to do so since 2000. Now with 47% of industry capacity in bankruptcy, the playing field looks set to become even more lopsided pressuring non-bankrupt legacies to lower costs further and low cost carriers to reassess their shrinking CASM advantage. *** CAPACITY PULLBACK. Over the past 20 years, bankrupt carriers decreased capacity by 5-10% on avg in the year following their filing. If we assume DAL and NWAC shrink by 7.5% (the midpoint) in '06, our domestic industry ASM forecast goes from +2% y/y to flat, which could potentially be favorable for airline pricing (yields). *** NWAC AND DAL INTIMATE CAPACITY RESTRAINT. After their filing yesterday, NWAC's CEO indicated 4Q:05 capacity could decline 5-6% y/y, while Delta announced plans to accelerate its fleet simplification plan, removing four aircraft types by the end of 2006. *** BIGGEST BENEFICIARIES LIKELY TO BE LOW COST CARRIERS. NWAC and DAL account for roughly 26% of domestic capacity, which, if trimmed by 7.5% equates to a 2% pt reduction in industry capacity. We believe LCC-heavy routes are likely to see a disproportionate benefit from potential reductions at DAL and NWAC, with AAI, AWA, and JBLU in particular having an easier path for growth. -

363 Part 238—Contracts With

Immigration and Naturalization Service, Justice § 238.3 (2) The country where the alien was mented on Form I±420. The contracts born; with transportation lines referred to in (3) The country where the alien has a section 238(c) of the Act shall be made residence; or by the Commissioner on behalf of the (4) Any country willing to accept the government and shall be documented alien. on Form I±426. The contracts with (c) Contiguous territory and adjacent transportation lines desiring their pas- islands. Any alien ordered excluded who sengers to be preinspected at places boarded an aircraft or vessel in foreign outside the United States shall be contiguous territory or in any adjacent made by the Commissioner on behalf of island shall be deported to such foreign the government and shall be docu- contiguous territory or adjacent island mented on Form I±425; except that con- if the alien is a native, citizen, subject, tracts for irregularly operated charter or national of such foreign contiguous flights may be entered into by the Ex- territory or adjacent island, or if the ecutive Associate Commissioner for alien has a residence in such foreign Operations or an Immigration Officer contiguous territory or adjacent is- designated by the Executive Associate land. Otherwise, the alien shall be de- Commissioner for Operations and hav- ported, in the first instance, to the ing jurisdiction over the location country in which is located the port at where the inspection will take place. which the alien embarked for such for- [57 FR 59907, Dec. 17, 1992] eign contiguous territory or adjacent island. -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

General Aviation Activity and Airport Facilities

New Hampshire State Airport System Plan Update CHAPTER 2 - AIRPORT SYSTEM INVENTORY 2.1 INTRODUCTION This chapter describes the existing airport system in New Hampshire as of the end of 2001 and early 2002 and served as the database for the overall System Plan. As such, it was updated throughout the course of the study. This Chapter focuses on the aviation infrastructure that makes up the system of airports in the State, as well as aviation activity, airport facilities, airport financing, airspace and air traffic services, as well as airport access. Chapter 3 discusses the general economic conditions within the regions and municipalities that are served by the airport system. The primary purpose of this data collection and analysis was to provide a comprehensive overview of the aviation system and its key elements. These elements also served as the basis for the subsequent recommendations presented for the airport system. The specific topics covered in this Chapter include: S Data Collection Process S Airport Descriptions S Airport Financing S Airport System Structure S Airspace and Navigational Aids S Capital Improvement Program S Definitions S Scheduled Air Service Summary S Environmental Factors 2.2 DATA COLLECTION PROCESS The data collection was accomplished through a multi-step process that included cataloging existing relevant literature and data, and conducting individual airport surveys and site visits. Division of Aeronautics provided information from their files that included existing airport master plans, FAA Form 5010 Airport Master Records, financial information, and other pertinent data. Two important element of the data collection process included visits to each of the system airports, as well as surveys of airport managers and users. -

Taxation of Fractional Programs: Flying Over Uncharted Waters Philip E

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 67 | Issue 2 Article 3 2002 Taxation of Fractional Programs: Flying Over Uncharted Waters Philip E. Crowther Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Philip E. Crowther, Taxation of Fractional Programs: Flying Over Uncharted Waters, 67 J. Air L. & Com. 241 (2002) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol67/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. TAXATION OF FRACTIONAL PROGRAMS: "FLYING OVER UNCHARTED WATERS" PHILIP E. CROWTHER* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................. 243 A. GENERAL DESIGN OF THE PROGRAM ............. 243 1. The Basic Agreements ........................ 243 2. General Principles ........................... 244 3. Operation of the Program..................... 246 4. Economic Analysis of the Program............. 249 5. Tax Analysis of the Program ................. 251 II. FEDERAL TRANSPORTATION TAX .............. 251 A. THE GENERAL RULES ........................... 251 1. The Transportation Tax ..................... 251 2. Taxation of Use of Own Aircraft .............. 256 3. Taxation of Joint Ownership Agreement ....... 261 4. Taxation of Dry Lease Exchange .............. 262 B. CHARACTERIZATION OF FRACTIONAL PROGRAMS.. 264 1. The FractionalCompany Rulings ............. 264 2. Executive Jet Aviation ........................ 267 3. Critique..................................... 270 C. CONSEQUENCES AND REMAINING ISSUES ......... 278 III. INCOME TAX ISSUES ............................. 279 A. THE GENERAL RULES ........................... 279 1. The Income Tax ............................. 279 * Attorney, Law Offices of Phil Crowther, a Kansas legal practice limited to aviation business and tax law. From 1986 to 1999, he was the Tax Manager and Assistant Treasurer at Cessna Aircraft.