The Hawaiian Island Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of Hawaii Community Health Needs Assessment

State of Hawaii Community Health Needs Assessment February 28, 2013 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Approach ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Data Sources and Methods ........................................................................................................................... 4 Areas of Need ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Selected Priority Areas ................................................................................................................................. 6 Note to the Reader ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Summary of CHNA Report Objectives and context ............................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Healthcare Association of Hawaii ................................................................................................ -

Albatross Or Mōlī (Phoebastria Immutabilis) Black-Footed Albatross Or Ka’Upu (Phoebastria Nigripes) Short-Tailed Albatross (Phoebastria Albatrus)

Hawaiian Bird Conservation Action Plan Focal Species: Laysan Albatross or Mōlī (Phoebastria immutabilis) Black-footed Albatross or Ka’upu (Phoebastria nigripes) Short-tailed Albatross (Phoebastria albatrus) Synopsis: These three North Pacific albatrosses are demographically similar, share vast oceanic ranges, and face similar threats. Laysan and Black-footed Albatrosses nest primarily in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, while the Short-tailed Albatross nests mainly on islands near Japan but forages extensively in U.S. waters. The Short-tailed Albatross was once thought to be extinct but its population has been growing steadily since it was rediscovered in 1951 and now numbers over 3,000 birds. The Laysan is the most numerous albatross species in the world with a population over 1.5 million, but its trend has been hard to determine because of fluctuations in number of breeding pairs. The Black-footed Albatross is one-tenth as numerous as the Laysan and its trend also has been difficult to determine. Fisheries bycatch caused unsustainable mortality of adults in all three species but has been greatly reduced in the past 10-20 years. Climate change and sea level rise are perhaps the greatest long-term threat to Laysan and Black-footed Albatrosses because their largest colonies are on low-lying atolls. Protecting and creating colonies on higher islands and managing non-native predators and human conflicts may become keys to their survival. Laysan, Black-footed, and Short-tailed Albatrosses (left to right), Midway. Photos Eric VanderWerf Status -

M U It I Resou Rce Forest Statistics for Molokai, Hawaii

United States Department of Agriculture Mu It iresou rce Forest Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Statistics for Resource Bulletin PNW-136 June 1986 Molokai, Hawaii Michael G. Buck, Patrick G. Costales, and Katharine McDuffie This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Text errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Authors MICHAEL G. BUCK and PATRICK G. COSIALLS are resource evaluation foresters with the Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wild- life in Honolulu, Hawaii. KATHARINE MCDUFFlt is a computer programmer/analyst at the Pacific Northwest Research Sta- tion, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, P.O. Box 3890, Portland, Oregon 97208. Abstract Summary Buck, Michael G.; Costales, Patrick G.; lhe island of Molokai, Hawaii, totals McDuf f ie, Katharine. Mu1 t i resource 163,211 acres, of which an estimated forest statistics for Molokai, Hawaii. 57,598 acres are forested --23,494 acres Resour. Bull. PNW-136. Portland, OR: classified as timberland and 34,104 acres U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest as other forest land. Previous inven- Service, Pacific Northwest Research tories show an additional estimated Station; 1986. 18 p. growing-stock volume of 4.2 million cubic feet on forest plantations, and an esti- This report summarizes a 1983 multire- mated total volume of 5.5 million cubic source forest inventory of the island of feet of a fuel-producing species growing Molokai, Hawaii. lables of forest area, on other forest land. Erosion occurs on timber volume, vegetation type, owner- only 7 percent of the island, the major- ship, land class, and wildlife are ity (85 percent) outside the forest re- presented. -

Laysan and Black-Footed Albatross Nesting Pairs at All Known Breeding Sites (Data from USFWS Unpublished Data Except As Noted Below)

A Conservation Action Plan for Black-footed Albatross (Phoebastria nigripes) and Laysan Albatross (P. immutabilis) Photograph by Marc D. Romano, USFWS Version 1.0 Contributors This Conservation Action Plan was compiled by Maura B. Naughton, Marc D. Romano and Tara S. Zimmerman, but it could not have been accomplished without the guidance, support, and input of the workshop participants and additional contributors that assisted with the development and review of this plan. Contributors included Joe Arceneaux, Greg Balogh, Jeremy Bisson, Louise Blight, John Burger, John Cusick, Kim Dietrich, Ann Edwards, Lyle Enriquez, Myra Finkelstein, Shannon Fitzgerald, Elizabeth Flint, Holly Freifeld, Eric Gilman, Tom Goode, Aaron Hebshi, Burr Heneman, Bill Henry, Michelle Hester, Jenny Hoskins, David Hyrenbach, Bill Kendall, Irene Kinan-Kelly, John Klavitter, Kathy Kuletz, Rebecca Lewison, James Ludwig, Ed Melvin, Ken Morgan, Mark Ono, Jayme Patrick, Kim Rivera, Scott Shaffer, Paul Sievert, David Smith, Jo Smith, Rob Suryan, Yonat Swimmer, Cynthia Vanderlip, Lewis VanFossen, Christine Volinski, Bill Wilson, Lee Ann Woodward, Lindsay Young, Stephanie Zador, Brenda Zaun, Michele Zwartjes. This version also benefited from the review and comments of Shelia Conant, John Croxall, Jaap Eijzenga, Falk Huettman, Mark Seamans, Ben Sullivan, and Jennifer Wheeler. Michelle Kappes and Scott Shaffer graciously provided access to unpublished data. Recommended Citation Naughton, M. B, M. D. Romano, T. S. Zimmerman. 2007. A Conservation Action Plan for Black-footed -

Narrative 05.01 Great Circle Distances Between

Table Number Table Name (Click on the table number to go to corresponding table) Narrative 05.01 Great Circle Distances Between Specified Places 05.02 Latitudes and Longitudes of Selected Places 05.03 Time Differences Between Honolulu and Selected Cities 05.04 Widths and Depths of Channels 05.05 General Coastline and Tidal Shoreline of Counties and Islands 05.06 Land and Water Area within the Fishery Conservation Zone 05.07 Land Area of Counties: 2000 05.08 Land Area of Islands: 2000 05.09 Major and Minor Islands in the Hawaiian Archipelago 05.10 Area and Depth of Selected Craters 05.11 Elevations of Major Summits 05.12 Major Named Waterfalls, by Islands 05.13 Major Streams, by Islands 05.14 Lakes and Lake-Like Waters, by Islands 05.15 Length and Width of Selected Beaches 05.16 Miscellaneous Geographic Statistics, by Island 05.17 Volcanic Eruptions: Mauna Loa 1950 to 1984, Kilauea 1969 to 2005 05.18 Major Earthquakes: 1838 to 2004 05.19 Earthquakes with Intensities on Oahu of V or Greater: 1859 to 2004 05.20 Tsunamis with Run-up of 2 Meters (6.6 feet) or More: 1819 to 2005 05.21 Major Dams 05.22 Fresh Water Use, by Type, by Counties: 2000 05.23 Water Services and Consumption, for County Waterworks: 2003 to 2005 05.24 Water Withdrawals by Source and Major Use, for the United States and Hawaii: 2000 05.25 Top 25 Water Users on Oahu: May 2004 to April 2005 05.26 Hazardous Waste Sites, Threats and Contaminants on Oahu 05.27 Toxic Chemical Releases in 2003, Hazardous Waste Sites in 2004, and Hazardous Waste Generated, Shipped, and Received -

Kumulipo: Northwestern Hawaiian Island Names a Native Hawaiian Cosmogonic Chant

1779 Lili‘uokalani’s party that Captain Cook’s men spend time with landed on Nihoa or Bird Photo courtesy of a chief’s canoe headed out to Ka‘ula: Island. David Gulko. 1200 A.D. ca. 1885 The Office of “One canoe belonging to some Pele, the Hawaiian Fire-Goddess, and Atoui [Kaua‘i] Chief staid (old her family arrive in Nihoa. Hawaiian 1786 English) with us till Sunset, and then Rolett went towards the Island Outoura Captain La Perouse, the first Affairs (OHA) [Ka‘ula] which was 4 miles distant to Photo altered European to sail past He nalu haki käkala, he nalu courtesy of the SE. Their business, they told us, Mokumanamana, names it in The sea was rough and choppy, but the was created by Bishop was to catch red birds, and the next waves honor of the French Minister of Museum day they intended going to E ‘imi ana i ka ‘äina e hiki aku ai. Necker Island the state Archives. Finance, Jacques Necker. Tomogoopappa [Mokupäpapa] for Bore us surely on to our destined shore— Emory 8 Turtle.” ‘O Nihoa ka ‘äina a mäkou i Photo altered courtesy of Bishop Museum Archives. Constitutional Burney M., March 1779; 631 pae mua aku ai: The rock Nihoa, the first land we Photo courtesy of Convention of The feathers of the Red-tail touched; Bishop Museum. 1789 Lele a‘e nei mäkou, kau i uka Pearl and Hermes 1978 as a pub- Tropicbird are coveted by Native Atoll. Captain Douglas is the first European to o Nihoa. Hawaiians for making sacred Bowl Hill from the northwest, lic trust, man- view Nihoa. -

The Natural History of French Frigate Shoals, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 150 THE NATURAL HISTORY OF FRENCH FRIGATE SHOALS, NORTHWESTERN HAWAIIAN ISLANDS by A. Binion Amerson, Jr. Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION with the assistance of The Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife US. Department of the Interior Washington D.C., U.S.A. December 20, 1971 days at French Frigate Shoals on 10 different survey trips. The initial results of BSFW and POBSP investigations, as well as previously published material, are discussed herein; special emphasis is focused on the vertebrate terrestrial fauna and the vascular flora. DESCRIPTION French Frigate Shoals, lying between the latitudes of 2j027'18" and Y3°52'50" North and the longitudes 166"Oj114" and 166°2~'~4"West (USCGS Chart 4172), is given an official location of 2j045'N x 166°10'W by the U.S. Department of the Interior (Office of Geography, 1956: 6). In 1786 La Perouse (1799) named this new atoll --Basee dee Fregates Francaisee, or Shoal of the French Frigates, because it nearly proved to be the termination of his voyage. Several variations of the name have been used over the years--French Frigate Shoal, French Frigates Shoal, and French Frigate Shoals. On 1 October 1924 the U.S. Geographic Board of Names selected French Frigate Shoal as the official name. In July 1954, however, the Board changed its collective mind and adopted French Frigate Shoals. The atoll consists of a crescent-shaped reef on a 20-fathom-deep oval platform,1 whose long axis is 19 nautical miles in a northwest to southeast direction (Fig. 2). -

Archaeological Literature Review and Field Inspection

Archaeological Literature Review and Field Inspection Report for the Nāwiliwili-Ahukini Bike Path Project Nāwiliwili, Kalapakī and Hanamā‘ulu Ahupua‘a Līhu‘e District, Kaua‘i Island TMK: (4) 3-2-004; 3-5-001, 002 & 3-6-002, 019, 020, and various rights-of-way between various plats Prepared for R.M. Towill Corporation Prepared by Chris Monahan, Ph.D. and Hallett H. Hammatt, Ph.D. Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i, Inc. Kailua, Hawai‘i (Job Code: NAWILIWILI 1) July 2008 O‘ahu Office Maui Office P.O. Box 1114 16 S. Market Street, Suite 2N Kailua, Hawai‘i 96734 Wailuku, Hawai‘i 96793 Ph.: (808) 262-9972 www.culturalsurveys.com Ph: (808) 242-9882 Fax: (808) 262-4950 Fax: (808) 244-1994 Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: NAWILIWILI 1 Management Summary Management Summary Reference Archaeological Literature Review and Field Inspection Report for the Nāwiliwili-Ahukini Bike Path Project, Nāwiliwili, Kalapakī and Hanamā‘ulu Ahupua‘a, Līhue District, Kaua‘i Island, TMK: (4) 3-2 004; 3-5-001, 002 & 3-6-002, 019, 020, and various rights-of-way between various plats Date May 2008 Project Number Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i (CSH) Job Code NAWILIWILI 1 Investigation Permit The field inspection was conducted under archaeological permit Number number 08-14 issued by the Hawai‘i State Historic Preservation Division (SHPD), Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR), per Hawai‘i Administrative Rules (HAR) Chapter 13-282. Project Location The project area is located in coastal and near-coastal portions of three ahupua‘a in Līhu‘e District, Island of Kaua‘i: Hanamā‘ulu, Kalapakī and Nāwiliwili. -

Final Environmental Assessment Lehua Island Ecosystem Restoration Project July 2017

Final Environmental Assessment Lehua Island Ecosystem Restoration Project July 2017 Co-Lead Agency: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Forestry and Wildlife Cooperating Federal Agencies: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Coast Guard U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services, National Wildlife Research Center i Executive Summary Lehua Island is a 115 hectare island located 1.2 km off the northern shore of Niʻihau (a privately owned, 18,650 hectare island). Lehua is a state-designated seabird sanctuary managed by the Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) and federally owned by the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG). Lehua is one of Hawaiʻi’s most important seabird colonies because of its size and height above sea level. It also offers an opportunity for restoring an island ecosystem in the main Hawaiian Islands. DLNR-Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW), in conjunction with federal sponsors U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), technical partner Island Conservation (IC), and the cooperating members of the Lehua Island Restoration Steering Committee (LIRSC) are proposing to complete the eradication of rats from Lehua Island so further restoration efforts can move forward in the future. The LIRSC is a multidisciplinary stakeholder body including representatives from DOFAW, USFWS, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services (USDA), U.S. Coast Guard (USCG), National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG), the owners of Niʻihau, and IC. In 2005, DOFAW and the USFWS embarked on a plan to restore Lehua Island. -

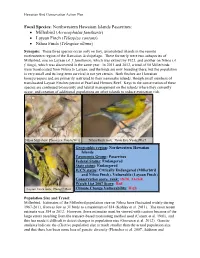

Focal Species: Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Passerines: Millerbird (Acrocephalus Familiaris) Laysan Finch (Telespiza Cantans) Nihoa Finch (Telespiza Ultima)

Hawaiian Bird Conservation Action Plan Focal Species: Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Passerines: Millerbird (Acrocephalus familiaris) Laysan Finch (Telespiza cantans) Nihoa Finch (Telespiza ultima) Synopsis: These three species occur only on tiny, uninhabited islands in the remote northwestern region of the Hawaiian Archipelago. There formerly were two subspecies of Millerbird, one on Laysan (A. f. familiaris), which was extinct by 1923, and another on Nihoa (A. f. kingi), which was discovered in the same year. In 2011 and 2012, a total of 50 Millerbirds were translocated from Nihoa to Laysan, and the birds are now breeding there, but the population is very small and its long-term survival is not yet certain. Both finches are Hawaiian honeycreepers and are primarily restricted to their namesake islands, though small numbers of translocated Laysan Finches persist at Pearl and Hermes Reef. Keys to the conservation of these species are continued biosecurity and habitat management on the islands where they currently occur, and creation of additional populations on other islands to reduce extinction risk. Nihoa Millerbird. Photo Eric VanderWerf Nihoa Finch male. Photo Eric VanderWerf Geographic region: Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Taxonomic Group: Passerines Federal Status: Endangered State status: Endangered IUCN status: Critically Endangered (Millerbird and Nihoa Finch), Vulnerable (Laysan Finch) Conservation score, rank: 18/20, At-risk Watch List 2007 Score: Red Laysan Finch male. Photo C. Rutt Climate Change Vulnerability: High Population Size and Trend: Millerbird. Estimates of the Millerbird population size on Nihoa have fluctuated widely during 1967-2011, from as few as 31 birds to a maximum of 814 (Kohley et al. 2011). -

2008-10-23-KA-FSEA-Lehua-Island

Final Supplemental Environmental Assessment Lehua Island Ecosystem Restoration Project October 2008 Lead Agencies: U.S. Department of Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Forestry and Wildlife Cooperating Agency: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Coast Guard Points of Contact: Chris Swenson Pacific Islands Coastal Program Coordinator U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Honolulu, Hawai‘i (808) 792-9400 [email protected] and Thomas Kaiakapu Division of Forestry and Wildlife Lihue, Hawai‘i (808) 274-3433 Thomas.J.Kaiakapu@ hawaii.gov Responsible Officials: Patrick Leonard, Field Supervisor Paul J. Conry, Administrator Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Division of Forestry and Wildlife U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Department of Land and Natural Resources 300 Ala Moana Blvd., Rm 3-122 1151 Punchbowl St., Rm 325 Honolulu, HI 96850 Honolulu, HI 96813 Prepared in compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act and Hawai’i HRS 343 and all associated regulations. Cover photo courtesy of Kenneth Wood 2 Executive Summary Lehua is an uninhabited island in Kaua‘i County, Hawai‘i located approximately 150 miles north-northwest of Honolulu, less than a mile north of Ni‘ihau, and approximately 20 miles west of the island of Kaua‘i. Its three-dimensional surface area is approximately 310 acres, although a variety of lower acreage figures are cited, likely based on estimates from 2-dimensional maps and images. The island is Federal property administered by the U.S. Coast Guard, which maintains a solar-powered navigational beacon near the 702-foot summit. -

Kūkulu Manamana: Ritual Power and Religious

KŪKULU MANAMANA: RITUAL POWER AND RELIGIOUS EXPANSION IN HAWAIʻI THE ETHNO-HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDY OF MOKUMANAMANA AND NIHOA ISLANDS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ANTHROPOLOGY DECEMBER 2012 By Kekuewa Scott T. Kikiloi Dissertation Committee: Michael Graves, Chairperson Jim Bayman Ty Kāwika Tengan Ben Finney Kēhaunani Abad Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa Copyright 2012 Kekuewa Scott T. Kikiloi ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A sincere and profound expression of gratitude is expressed here towards the following organizations for their vital support of this research project: Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (National Oceanic Atmospheric Adminstration, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and State of Hawaiʻi), Office of Hawaiian Affairs, the Papahānaumokuākea Cultural Working Group, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies, University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo Geochemistry Laboratory, University of New Mexico the Radiogenic Isotope Laboratory and Anthropology Department, the Kohala Center, the Kamehameha Schools, ʻAha Pūnana Leo, the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, and the Edith Kanakaʻole Foundation. This research also relied on the following individuals that contributed valuable time and/or assistance to this project including: Jo Lynn Gunness, Dr. Terry Hunt, Dr. Eric Hellenbrand, Dr. Celia Smith and Cherly Squair (University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa); Dr. Peter Mills and Dr. Steve Lunblad at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo); Dr. Yemane Asmerom and Dr. Keith Prufer at the University of New Mexico; Dr. Paul Jokiel and Dr. Kuʻulei Rodgers at Hawaiʻi Institute for Marine Biology; Dr. Peter Viteousek at Stanford University; Gail Murakami at AARII; Kaylene Keller and Daniel Turner at the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration; Betty Kam, Kamalu Dupreez, Jenny Kahn, and Clyde Imada at the Bishop Museum; Alan Carpenter at State Parks; and Amanda Sims and Kanani Frazier for their help with the graphics.